Great Entertainers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARSC Journal, Spring 1992 69 Sound Recording Reviews

SOUND RECORDING REVIEWS Chicago Symphony Orchestra: The First Hundred Years CS090/12 (12 CDs: monaural, stereo; ADD)1 Available only from the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, 220 S. Michigan Ave, Chicago, IL, for $175 plus $5 shipping and handling. The Centennial Collection-Chicago Symphony Orchestra RCA-Victor Gold Seal, GD 600206 (3 CDs; monaural, stereo, ADD and DDD). (total time 3:36:3l2). A "musical trivia" question: "Which American symphony orchestra was the first to record under its own name and conductor?" You will find the answer at the beginning of the 12-CD collection, The Chicago Symphony Orchestra: The First 100 Years, issued by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO). The date was May 1, 1916, and the conductor was Frederick Stock. 3 This is part of the orchestra's celebration of the hundredth anniversary of its founding by Theodore Thomas in 1891. Thomas is represented here, not as a conductor (he died in 1904) but as the arranger of Wagner's Triiume. But all of the other conductors and music directors are represented, as well as many guests. With one exception, the 3-CD set, The Centennial Collection: Chicago Symphony Orchestra, from RCA-Victor is drawn from the recordings that the Chicago Symphony made for that company. All were released previously, in various formats-mono and stereo, 78 rpm, 45 rpm, LPs, tapes, and CDs-as the technologies evolved. Although the present digital processing varies according to source, the sound is generally clear; the Reiner material is comparable to RCA-Victor's on-going reissues on CD of the legendary recordings produced by Richard Mohr. -

Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt487035r5 No online items Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Michael P. Palmer Processing partially funded by generous grants from Jim Deeton and David Hensley. ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives 909 West Adams Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90007 Phone: (213) 741-0094 Fax: (213) 741-0220 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.onearchives.org © 2009 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Coll2007-020 1 Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Collection number: Coll2007-020 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives Los Angeles, California Processed by: Michael P. Palmer, Jim Deeton, and David Hensley Date Completed: September 30, 2009 Encoded by: Michael P. Palmer Processing partially funded by generous grants from Jim Deeton and David Hensley. © 2009 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Ralph W. Judd collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Dates: 1848-circa 2000 Collection number: Coll2007-020 Creator: Judd, Ralph W., 1930-2007 Collection Size: 11 archive cartons + 2 archive half-cartons + 1 records box + 8 oversize boxes + 19 clamshell albums + 14 albums.(20 linear feet). Repository: ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. Los Angeles, California 90007 Abstract: Materials collected by Ralph Judd relating to the history of cross-dressing in the performing arts. The collection is focused on popular music and vaudeville from the 1890s through the 1930s, and on film and television: it contains few materials on musical theater, non-musical theater, ballet, opera, or contemporary popular music. -

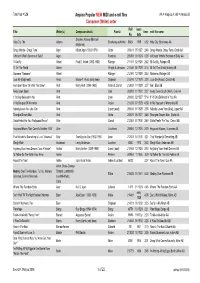

Ampico Popular NEW MIDI and E-Roll Files Composer

Total files = 536 Ampico Popular NEW MIDI and e-roll files AA = Ampico A, AB = Ampico B Composer (Writer) order Roll issue Title Writer(s) Composer details Pianist time midi file name No. date Stephen Adams (Michael Holy City, The Adams Brockway as Kmita 56824 1919 4:52 Holy City, Brockway AA Maybrick) Crazy Words - Crazy Tune Ager Milton Ager (1893-1979) Grofe 208611 05 1927 2:48 Crazy Words, Crazy Tune, Grofe AA I Wonder What's Become of Sally? Ager Fairchild 205191 09 1924 4:28 I Wonder What's Become of Sally AA I'll Get By Ahlert Fred E. Ahlert (1892-1953) Rainger 211171 02 1929 2:42 I'll Get By, Rainger AB I'll Tell The World Ahlert Wright & Johnston 211541 05 1929 3:14 I'll Tell The World (Ahlert) AB Marianne "Marianne" Ahlert Rainger 212191 12 1929 2:44 Marianne, Rainger AB Love Me (Deja) waltz Aivaz Morse-T. Aivaz (only item) Shipman 212241 12 1929 3:20 Love Me (Aivaz), Carroll AB Am I Blue? from "On With The Show" Akst Harry Akst (1894-1963) Arden & Carroll 212031 10 1929 3:37 Am I Blue AB Away Down South Akst Clair 203051 11 1922 2:37 Away Down South (Akst), Clair AA If I'd Only Believed In You Akst Lane 208383 02 1927 5:14 If I'd Only Believed In You AA In My Bouquet Of Memories Akst Arden 210233 07 1928 4:58 In My Bouquet of Memories AB Nobody Loves You Like I Do Akst Lopez (asst) 205531 01 1925 2:38 Nobody Loves You (Akst), Lopez AA Shanghai Dream Man Akst Grofe 208621 05 1927 3:48 Shanghai Dream Man, Grofe AA Gotta Feelin' For You "Hollywood Revue" Alter Carroll 212351 01 1930 2:49 Gotta Feelin' For You, Carroll AB Hugs and -

Judy Garland (1922-1969)

1/22 Data Judy Garland (1922-1969) Pays : États-Unis Sexe : Féminin Naissance : Grand-Rapid (S. D.), 10-06-1922 Mort : Londres, 22-01-1969 Note : Chanteuse et actrice américaine Autre forme du nom : Frances Gumm (1922-1969) ISNI : ISNI 0000 0000 8380 6106 (Informations sur l'ISNI) Judy Garland (1922-1969) : œuvres (255 ressources dans data.bnf.fr) Œuvres audiovisuelles (y compris radio) (45) "Un enfant attend. - [2]" "Un enfant attend. - [2]" (2016) (2016) de Ernest Gold et autre(s) de Ernest Gold et autre(s) avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur "Le magicien d'Oz" "Le magicien d'Oz" (2013) (2013) de Victor Fleming et autre(s) de Victor Fleming et autre(s) avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur "La jolie fermière" "Till the clouds roll by" (2013) (2012) de George Wells et autre(s) de Richard Whorf et autre(s) avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur "Le chant du Missouri" "Meet me in St. Louis. - Vincente Minnelli, réal.. - [2]" (2012) (2012) de Vincente Minnelli et autre(s) de Vincente Minnelli et autre(s) avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur "Le chant du Missouri" "La pluie qui chante. - Richard Whorf, réal.. - [2]" (2011) (2010) de Vincente Minnelli et autre(s) de George Wells et autre(s) avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur data.bnf.fr 2/22 Data "Le chant du Missouri" "Le magicien d'Oz" (2009) (2009) de Vincente Minnelli et autre(s) de Victor Fleming et autre(s) avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur "The pirate" "La danseuse des Folies Ziegfeld" (2008) (2007) de Vincente Minnelli et autre(s) de Sonya Levien et autre(s) avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur "Parade de printemps" "Un enfant attend. -

The Digital Deli Online - List of Known Available Shows As of 01-01-2003

The Digital Deli Online - List of Known Available Shows as of 01-01-2003 $64,000 Question, The 10-2-4 Ranch 10-2-4 Time 1340 Club 150th Anniversary Of The Inauguration Of George Washington, The 176 Keys, 20 Fingers 1812 Overture, The 1929 Wishing You A Merry Christmas 1933 Musical Revue 1936 In Review 1937 In Review 1937 Shakespeare Festival 1939 In Review 1940 In Review 1941 In Review 1942 In Revue 1943 In Review 1944 In Review 1944 March Of Dimes Campaign, The 1945 Christmas Seal Campaign 1945 In Review 1946 In Review 1946 March Of Dimes, The 1947 March Of Dimes Campaign 1947 March Of Dimes, The 1948 Christmas Seal Party 1948 March Of Dimes Show, The 1948 March Of Dimes, The 1949 March Of Dimes, The 1949 Savings Bond Show 1950 March Of Dimes 1950 March Of Dimes, The 1951 March Of Dimes 1951 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1951 March Of Dimes On The Air, The 1951 Packard Radio Spots 1952 Heart Fund, The 1953 Heart Fund, The 1953 March Of Dimes On The Air 1954 Heart Fund, The 1954 March Of Dimes 1954 March Of Dimes Is On The Air With The Fabulous Dorseys, The 1954 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1954 March Of Dimes On The Air 1955 March Of Dimes 1955 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1955 March Of Dimes, The 1955 Pennsylvania Cancer Crusade, The 1956 Easter Seal Parade Of Stars 1956 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1957 Heart Fund, The 1957 March Of Dimes Galaxy Of Stars, The 1957 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1957 March Of Dimes Presents The One and Only Judy, The 1958 March Of Dimes Carousel, The 1958 March Of Dimes Star Carousel, The 1959 Cancer Crusade Musical Interludes 1960 Cancer Crusade 1960: Jiminy Cricket! 1962 Cancer Crusade 1962: A TV Album 1963: A TV Album 1968: Up Against The Establishment 1969 Ford...It's The Going Thing 1969...A Record Of The Year 1973: A Television Album 1974: A Television Album 1975: The World Turned Upside Down 1976-1977. -

The Quitaque Post Your Home-Owned Newspaper

THE QUITAQUE POST YOUR HOME-OWNED NEWSPAPER VOLUME XXII QUITAGILTE BRISCOE COUNTY. TEXAS THURSDAY JUNE 17, 1948 5c Per Copy NUMBER 22 This And That About Burns Are Fatal To Sailors Thumb Ride Boyles-Rogers Vows Baby Dies After Baptist Church News One Thing and Another Small Sheila Guest Take Car And Money Exchanged June 11 Drinking Kerosene The Vacation Bible School at the This area was isit,d by scatter- A tragic accident took the life Christie Cox. of Jackson, Ala., a Funeral services were held for First Baptist Church is growing ed showers again Monday after- Cl the tiny daughter of Mr. ani ;Dung man about 30 years old, Rosa Lucero, 14 months old girl daily. Tuesday there were 125 en- noon. and in some sections heavy Mrs. Smith Guest. Tuesday morn- merchant seaman on leave from Sunday afternoon at 4:30 p.m. at rolled. The high attendance was rain and damaging hail fell. In the and the entire community was duty. was knocked in the be the home of her parents, Mr. and Monday with 110 registered pre- Gasoline community farmers who saddened and grieved with the re- with a bottle and relieved of his Mrs. Lucas Lucero in the last part sent. The kids are having the time had just completed replanting af- latives over the loss of a lovely automobile and $125.00 in cash of town. Rosa was born April 6, of their lives—softball for the ter last week's hall and wind storm child. while acting the Good Samaritan. 1947, died June 12, 1948, at 1:15 am. -

Broadway and Tin Pan Alley Introductory Essay

Broadway and Tin Pan Alley Introductory Essay “Way Down Upon the Hudson River: Tin Pan Alley's New York Triumph” Rachel Rubin, Professor of American Studies, University of Massachusetts Broadway in the 1920s was a showcase for the sweeping changes transforming American culture in the early 20th century, including new roles for women, the mixing of social classes in new settings like Prohibition-era speakeasies and creative innovation by African Americans in jazz clubs and music halls. Sons of immigrants from Europe -- including the Gershwins, Irving Berlin, Jerome Kern and Harold Arlen -- made up a large percentage of the new word and music smiths writing for Tin Pan Alley and Broadway’s musical revues. Their syncopated rhythms borrowed from the jazz craze and their lyrics helped create a vibrant, witty new American argot. Tin Pan Alley and Broadway contributed such classic standards as “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” (Berlin), “I Got Rhythm” (Gershwin and Gershwin), “Ol’Man River,” (Kern and Hammerstein), “Stormy Weather” (Arlen and Koehler), “Ain’t Misbehavin’” (Razaf, Waller, Brooks), “Anything Goes” (Porter) and many more. These songs formed the musical backdrop of an era. The production of these songs also became big business. The first major book written about Tin Pan Alley was published in 1930 by Harvard professor Isaac Goldberg, and it was subtitled “A Chronicle of the American Popular Music Racket.” Goldberg’s humorous use of the word “racket” captured something about the origins of the name “Tin Pan Alley” given to the music composed by poorly-paid songwriters banging away in cubicles in downtown New York City on cheap pianos. -

Title Composer Lyricist Arranger Cover Artist Publisher Date Notes Wabash Blues Fred Meinken Dave Ringle Leo Feist Inc

Title Composer Lyricist Arranger Cover artist Publisher Date Notes Wabash Blues Fred Meinken Dave Ringle Leo Feist Inc. 1921 Wabash Cannon Ball Wm Kindt Wm Kindt NPS Calumet Music Co. 1939 High Bass arranged by Bill Burns Wabash Moon Dave Dreyer Dave Dreyer Irving Berlin Inc. 1931 Wagon Wheels Peter DeRose Billy Hill Shapiro, Bernstein & Co. 1934 Wagon Wheels Peter DeRose Billy Hill Geoffrey O'Hara Shapiro, Bernstein & Co., Inc. 1942 Arranged for male voices (T.T.B.B.) Wah-Hoo! Cliff Friend Cliff Friend hbk Crawford Music Corp. 1936 Wait for Me Mary Charlie Tobias Charlie Tobias Harris Remick Music Corp. 1942 Wait Till the Cows Come Home Ivan Caryll Anne Caldwell Chappell & Company Ltd 1917 Wait Till You Get Them Up In The Air, Boys Albert Von Tilzer Lew Brown EEW Broadway Music Corp. 1919 Waitin' for My Dearie Frederick Loewe Alan Jay Lerner Sam Fox Pub. Co. 1947 Waitin' for the Train to Come In Sunny Skylar Sunny Skylar Martin Block Music 1945 Waiting Harold Orlob Harry L. Cort Shapiro, Bernstein & Co. 1918 Waiting at the Church; or, My Wife Won't Let Me Henry E. Pether Fred W. Leigh Starmer Francis, Day & Hunter 1906 Waiting at the End of the Road Irving Berlin Irving Berlin Irving Berlin Inc. 1929 "Waiting for the Robert E. Lee" Lewis F. Muir L. Wolfe Gilbert F.A. Mills 1912 Waiting for the Robert E. Lee Lewis F. Muir L. Wolfe Gilbert Sigmund Spaeth Alfred Music Company 1939 Waiting in the Lobby of Your Heart Hank Thompson Hank Thompson Brenner Music Inc 1952 Wake The Town and Tell The People Jerry Livingston Sammy Gallop Joy Music Inc 1955 Wake Up, America! Jack Glogau George Graff Jr. -

The Many Faces of “Dinah”: a Prewar American Popular Song and the Lineage of Its Recordings in the U.S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE The Many Faces of “Dinah” The Many Faces of “Dinah”: A Prewar American Popular Song and the Lineage of its Recordings in the U.S. and Japan Edgar W. Pope 「ダイナ」の多面性 ──戦前アメリカと日本における一つの流行歌とそのレコード── エドガー・W・ポープ 要 約 1925年にニューヨークで作曲された「ダイナ」は、1920・30年代のアメリ カと日本両国におけるもっとも人気のあるポピュラーソングの一つになり、 数多くのアメリカ人と日本人の演奏家によって録音された。本稿では、1935 年までに両国で録音されたこの曲のレコードのなかで、最も人気があり流 行したもののいくつかを選択して分析し比較する。さらにアメリカの演奏家 たちによって生み出された「ダイナ」の演奏習慣を表示する。そして日本人 の演奏家たちが、自分たちの想像力を通してこの曲の新しい理解を重ねる中 で、レコードを通して日本に伝わった演奏習慣をどのように応用していった かを考察する。 1. Introduction “Dinah,” published in 1925, was one of the leading hit songs to emerge from New York City’s “Tin Pan Alley” music industry during the interwar period, and was recorded in the U.S. by numerous singers and dance bands during the late 1920s and 1930s. It was also one of the most popular songs of the 1930s in Japan, where Japanese composers, arrangers, lyricists and performers, inspired in part by U.S. records, developed and recorded their own versions. In this paper I examine and compare a selection of the American and Japanese recordings of this song with the aim of tracing lines ─ 155 ─ 愛知県立大学外国語学部紀要第43号(言語・文学編) of influence, focusing on the aural evidence of the recordings themselves in relation to their recording and release dates. The analysis will show how American recordings of the song, which resulted from complex interactions of African American and European American artists and musical styles, established certain loose conventions of performance practices that were conveyed to Japan and to Japanese artists. It will then show how these Japanese artists made flexible use of American precedents, while also drawing influences from other Japanese recordings and adding their own individual creative ideas. -

Complete List of Silent Films Featuring Journalists and Journalism 1920-1929 (Each Film Is Annotated in the Appendices 12-21)

Complete List of Silent Films Featuring Journalists and Journalism 1920-1929 (Each film is annotated in the appendices 12-21) 1920 Always Audacious Amateur Devil, An Amazing Woman, The Bab's Candidate (Newspaper) Beggar in Purple, A Behold My Wife (newspaper) Below The Surface (newspaper) Biff! Bang!! Bomb!!! Big Happiness (newspaper) Blind Youth (critics) Branded Woman, The (newspaper) Burton Holmes Travelogues Cameraman, The Capitol, The Chains of Evidence Cinderella's Twin (magazine) Clever Cubs Dangerous Love Deadline at Eleven Demoracy -- The Vision Restored Desperate Hero, The Devil's Pass Key, The Dinty Do the Dead Talk Editorial Horseplay Fear Market, The Figurehead, The Find the Girl (aka Beaucitron reporter) Flying Pat Food for Scandal Fourth Face, The (aka The Mystery of Washington Square) Go and Get It Great Round-Up, The Green Flame, The Heart of Twenty, The Hearst News No. 49 Held by the Enemy Heliotrope Herbert Kaufman Weekly, The Hidden Light, The Homespun Folks Honor Bound House of the Tolling Bell, The Hy Mayer Such is Life Series In the Heart of a Fool International News No. 5 International News No. 84 Jailbird, The Jerry on the Job: Bomb Idea, The Joyous Troublemaker, The Keyhole Reporter, The Law of the Yukon, The Leap Year Leaps Lion Man, The: Episode Two: Rope of Death Lion Man, The: Episode Three:Kidnappers Lion Man, The: Episode Four: Devilish Device, A Lion Man, The: Episode Five: In the Lion's Dean Lion Man, The: Episode Six: House of Horrors Lion Man, The: Episode Seven: Doomed Lion Man, The: Episode Eight: -

Viewed One of the First “Films Parlants” in 1930 in London

FROM GOLDEN AGE TO SILVER SCREEN: FRENCH MUSIC-HALL CINEMA FROM 1930-1950 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Rebecca H. Bias, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Judith Mayne, Advisor Professor Diane Birckbichler _________________________ Advisor Professor Charles D. Minahen Graduate Program in French and Italian Copyright by Rebecca H. Bias 2005 ABSTRACT This dissertation examines French music-hall cinema from 1930-1950. The term “music-hall cinema” applies to films that contain any or all of the following: music-hall performers, venues, mise en scène, revues, and music- hall songs or repertoire. The cinema industry in France owes a great debt to the music-hall industry, as the first short films near the turn of the century were actually shown as music-hall acts in popular halls. Nonetheless, the ultimate demise of the music hall was in part due to the growing popularity of cinema. Through close readings of individual films, the dynamics of music-hall films will be related to the relevant historical and cultural notions of the period. The music-hall motif will be examined on its own terms, but also in relation to the context or genre that underlies each particular film. The music-hall motif in films relies overwhelmingly on female performers and relevant feminist film theory of the 1970s will help support the analysis of female performance, exhibition, and relevant questions of spectatorship. Music-hall cinema is an important motif in French film, and the female performer serves as the prominent foundation in these films. -

Liner Notes, Visit Our Web Site

Irving Berlin “This Is the Life!” The Breakthrough Years: 1909–1921 by Rick Benjamin “Irving Berlin remains, I think, America’s Schubert.” —George Gershwin It was a perfect late summer evening in 2015. A crowd had gathered in the park of a small Pennsylvania town to hear the high-school band. I was there to support my trombonist son and his friends. The others were also mostly parents and relatives of “band kids,” with a sprinkling of senior citizens and dog walkers. As the band launched its “covers” of current pop hits toward the treetops, some in the crowd were only half-listening; their digital devices were more absorbing. But then it happened: The band swung into a new tune, and the mood changed. Unconsciously people seemed to sit up a bit straighter. There was a smattering of applause. Hands and feet started to move in time with the beat. The seniors started to sing. One of those rare “public moments” was actually happening. Then I realized what the band was playing—“God Bless America.” Finally, here was something solid—something that resonated, even with these teenaged performers. The singing grew louder, and the performance ended with the biggest applause of the night. “God Bless America” was the grandest music of the concert, a mighty oak amongst the scrub. Yet the name of its creator—Irving Berlin—was never announced. It didn’t need to be. A man on a bench nearby said to me, “I just love those Irving Berlin songs.” Why is that, anyway? And how still? Irving Berlin was a Victorian who rose to fame during the Ragtime Era.