Finding Balance Between Unity and Diversity: a Major Challenge to Democracy, Governance and National Unity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State of Rhode Island

2004 -- S 2981 ======= LC02951 ======= STATE OF RHODE ISLAND IN GENERAL ASSEMBLY JANUARY SESSION, A.D. 2004 ____________ S E N A T E R E S O L U T I O N COMMEMORATING THE ANNIVERSARY OF THE PAKISTAN RESOLUTION PASSED ON MARCH 23, 1940 Introduced By: Senators Issa, Tassoni, Perry, Pichardo, and Parella Date Introduced: March 23, 2004 Referred To: Senate held on desk 1 WHEREAS, During the period of time that India was attempting to gain their 2 independence from Great Britain, the subcontinent was also torn by an internal conflict between 3 its Hindu and Muslim populations. Each of these two communities wanted a separate area over 4 which they could rule; and 5 WHEREAS, The Muslims of India struggled to establish a separate homeland on the 6 basis of the Two Nation Theory. Despite their long association and interactions at various levels, 7 the Hindus and Muslims of India had remained two separate and distinct sociocultural entities; 8 and 9 WHEREAS, On March 23, 1940, the All India Muslim League, at Lahore, adopted a 10 resolution calling for a separate, independent Muslim homeland. Mohammad Ali Jinnah, founder 11 of Pakistan, working alongside leaders of the Indian subcontinent, freed Muslims from 200 years 12 of oppression under the British rule, paving the way for millions of Muslims to consider self-rule 13 and governance that would allow them to live freely according to their own religious and political 14 ideologies in life; and 15 WHEREAS, This day, called Pakistan Day, is observed in order to commemorate the 16 passage of the resolution. -

Pakistan Courting the Abyss by Tilak Devasher

PAKISTAN Courting the Abyss TILAK DEVASHER To the memory of my mother Late Smt Kantaa Devasher, my father Late Air Vice Marshal C.G. Devasher PVSM, AVSM, and my brother Late Shri Vijay (‘Duke’) Devasher, IAS ‘Press on… Regardless’ Contents Preface Introduction I The Foundations 1 The Pakistan Movement 2 The Legacy II The Building Blocks 3 A Question of Identity and Ideology 4 The Provincial Dilemma III The Framework 5 The Army Has a Nation 6 Civil–Military Relations IV The Superstructure 7 Islamization and Growth of Sectarianism 8 Madrasas 9 Terrorism V The WEEP Analysis 10 Water: Running Dry 11 Education: An Emergency 12 Economy: Structural Weaknesses 13 Population: Reaping the Dividend VI Windows to the World 14 India: The Quest for Parity 15 Afghanistan: The Quest for Domination 16 China: The Quest for Succour 17 The United States: The Quest for Dependence VII Looking Inwards 18 Looking Inwards Conclusion Notes Index About the Book About the Author Copyright Preface Y fascination with Pakistan is not because I belong to a Partition family (though my wife’s family Mdoes); it is not even because of being a Punjabi. My interest in Pakistan was first aroused when, as a child, I used to hear stories from my late father, an air force officer, about two Pakistan air force officers. In undivided India they had been his flight commanders in the Royal Indian Air Force. They and my father had fought in World War II together, flying Hurricanes and Spitfires over Burma and also after the war. Both these officers later went on to head the Pakistan Air Force. -

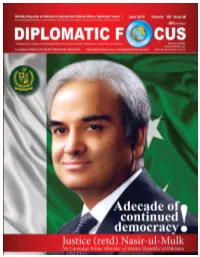

June 2018 Volume 09 Issue 06 “Publishing from Pakistan, United Kingdom/EU & Will Be Soon from UAE ”

June 2018 Volume 09 Issue 06 “Publishing from Pakistan, United Kingdom/EU & will be soon from UAE ” 09 10 19 31 09 Close and fraternal relations between Turkey is playing a very positive role towards the resolution Pakistan & Turkey are the guarantee of of different international issues. Turkey has dealt with the stability and prosperity in the region: Middle East crisis and especially the issue of refugees in a very positive manner, President Mamnoon Hussain 10 7th Caretaker PM of Pakistan Former Former CJP Nasirul Mulk was born on August 17, 1950 in CJP Nasirul Mulk Mingora, Swat. He completed his degree of Bar-at-Law from Inner Temple London and was called to the Bar in 1977. 19 President Emomali Rahmon expressed The sides discussed the issues of strengthening bilateral satisfaction over the friendly relations and cooperation in combating terrorism, extremism, drug multifaceted cooperation between production and transnational crime. Tajikistan & Pakistan 31 Colorful Cultural Exchanges between China and Pakistan are not only friendly neighbors, but also China and Pakistan two major ancient civilizations that have maintained close ties in cultural exchanges and mutual learning. The Royal wedding 2018 Since announcing their engagement in 13 November 2017, the world has been preparing for Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s royal wedding. The Duke and Duchess of Sussex begin their first day as a married couple following an emotional ceremony that captivated the nation and a night spent partying with close family and friends. 06 Diplomatic Focus June 2018 RBI Mediaminds Contents Group of Publications Electronic & Print Media Production House 09 Pakistan & Turkey Close and fraternal relations …: President Mamnoon Hussain 10 7th Caretaker PM of Pakistan Former CJP Nasirul Mulk 12 The Royal wedding2018 Group Chairman/CEO: Mian Fazal Elahi 14 Pakistan & Saudi Arabia are linked through deep historic, religious and cultural Chief Editor: Mian Akhtar Hussain relations Patron in Chief: Mr. -

21 Lc 123 0309 S. R

21 LC 123 0309 Senate Resolution 326 By: Senators Rahman of the 5th and Merritt of the 9th A RESOLUTION 1 Celebrating the anniversary of the signing of the Lahore Resolution on March 23, 1940, and 2 recognizing March 23, 2021, as Pakistan Day at the state capitol; and for other purposes. 3 WHEREAS, the United States and Pakistan are united by shared values, common interests, 4 and mutual respect, constantly striving to encourage greater tolerance, enforce the rule of 5 law, and uphold the principles of democracy; and 6 WHEREAS, Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah said that "the story of Pakistan, its 7 struggle and its achievement, is the very story of great human ideals, struggling to survive 8 in the face of great odds and difficulties"; these words ring true today as Pakistan works to 9 fulfill the vision of its founders; and 10 WHEREAS, we join the people of Pakistan and Pakistani American Friends of Atlanta 11 (PAFA) along with the Honorable Consul General of Pakistan in Houston Abrar H. Hashmi 12 in honoring these ideals and the valiant sacrifices made every day in the fight against violent 13 extremism; and S. R. 326 - 1 - 21 LC 123 0309 14 WHEREAS, we remember the message of "hope, courage, and confidence" the 15 Quaid-e-Azam expressed to the Pakistani people, and we continue to support efforts to strive 16 for a more peaceful and prosperous Pakistan; and 17 WHEREAS, the Lahore Resolution was adopted on March 23, 1940, during the All-India 18 Muslim League's three-day general session; written and prepared by Muhammad Zafarullah 19 Khan; and presented by A. -

I Leaders of Pakistan Movement, Vol.I

NIHCR Leadersof PakistanMovement-I Editedby Dr.SajidMehmoodAwan Dr.SyedUmarHayat National Institute of Historical and Cultural Research Centre of Excellence, Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad - Pakistan 2018 Leaders of Pakistan Movement Papers Presented at the Two-Day International Conference, April 7-8, 2008 Vol.I (English Papers) Sajid Mahmood Awan Syed Umar Hayat (Eds.) National Institute of Historical and Cultural Research Centre of Excellence, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad – Pakistan 2018 Leaders of Pakistan Movement NIHCR Publication No.200 Copyright 2018 All rights reserved. No part of this publication be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing from the Director, National Institute of Historical and Cultural Research, Centre of Excellence, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad. Enquiries concerning reproduction should be sent to NIHCR at the address below: National Institute of Historical and Cultural Research Centre of Excellence, New Campus, Quaid-i-Azam University P.O. Box 1230, Islamabad-44000. Tel: +92-51-2896153-54; Fax: +92-51-2896152 Email: [email protected] or [email protected] Website: www.nihcr.edu.pk Published by Muhammad Munir Khawar, Publication Officer Formatted by \ Title by Khalid Mahmood \ Zahid Imran Printed at M/s. Roohani Art Press, Sohan, Express Way, Islamabad Price: Pakistan Rs. 600/- SAARC countries: Rs. 1000/- ISBN: 978-969-415-132-8 Other countries: US$ 15/- Disclaimer: Opinions and views expressed in the papers are those of the contributors and should not be attributed to the NIHCR in any way. Contents Preface vii Foreword ix Introduction xi Paper # Title Author Page # 1. -

Board of Intermediate Education, Karachi Intermediate Examination, 2016 (Annual)

BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE EDUCATION, KARACHI INTERMEDIATE EXAMINATION, 2016 (ANNUAL) Date: 06.05.2016 PAKISTAN STUDIES (COMPULSORY) Max. Marks: 10 9:30 a.m. to 9:45 a.m. (Science, Home Economics & Medical Technology Groups) Time: 15 minutes SECTION ‘A’ The correct answers are (MULTIPLE CHOICE QUESTIONS) – (M.C.Qs.) highlighted in red colour. NOTE: i) This section consists of 20 part questions and all are to be answered. Write this Code No. in the Answerscript. Each question carries ½ mark. ii) Do not copy the part questions in your answerscript. Write only the answer in full against the proper number of the question and its part. iii) The code of your question paper is to be written in bold letters in the beginning of the answerscript. 1. Choose the correct answer for each from the given options: i) Pakistan day is celebrated on: * 20th March * 21st March * 22nd March * 23rd March ii) The head of the Boundary commission was: * Lord Mountbatten * Radcliffe * Lord Wavell * Sir Stafford Cripps iii) According to the 1973 constitution, the National language of Pakistan is: * Urdu * Punjabi * Bengali * English iv) Pakistan’s National flower is: * Rose * Lotus * Jasmine * Chrysanthemum v) The Educational, scientific and cultural institution of the United Nations Organization is: * UNICEF * WHO * ILO * UNESCO vi) The constitutional head of Pakistan is the: * President * Prime Minister * Speaker, National Assembly * Chairman, Senate vii) The border shared between Pakistan and Afghanistan is called: * Durand line * Turkham line * Karakoram highway* Shahrah-e-Pakistan viii) This city of Pakistan is famous for its international seaport and airport: * Lahore * Karachi * Quetta * Islamabad ix) Khilafat movement started in 1919 A.D. -

Conferment of Pakistan Civil Awards

CONFIDENTIAL F. No. tlt l20ll-Awards-l GOVERNMENTOF PAKISTAN CABINET SECRETARIAT (cABtNET DtVtStON) rrt*t*rr* PRESS RELEASE On the occasion of lndependence Day, 14th August, 2021., the President of the lslamic Republic of Pakistan has been pleased to confer the following 'Pakistan Civit Awards' on citizens of Pakistan as well as Foreign Nationals for showing excellence and courage in their respective fields. The investiture ceremony of these awards will take place on Pakistan Day, 23rd March, 2022:- I. NISHAN.I.IMTIAZ 1 Mr. Muhammad Naeem Science (Chemistry) (Punjab) 2 Mr. Nazar Muhammad Rashid alias N.M Literature Rashid (late) (Punjab) 3 Mr. Majeed Amjad alias Abdul Majeed (late) Literature (Punjab) II. HILAL-I.PAKISTAN 4 Mr. LiXiaopeng Services to Pakistan (China) 5 Mr. Zhou Xiaochuan Services to Pakistan (China) l[. H[AL-|{MIAZ 6 Dr. lnam ur Rehman Science (Nuclear Physics) (Punjab) 7 Dr. Qamar Mehboob Engineering (Nuclear) (Punjab ) r 8 Mr. Tahir lkram Engineering (Mechanical) (Punjab) 9 Mr. Jamshed Azim Hashmi Engineering (Sindh) (Electrical & Mechanical) 10 Mr. Rohail Hayat Art (Music Composer) (Punjab) TL Ms. Kishwar Naheed Literature (Punjab) IV. SITARA.I.PAKISTAN L2 Mr. Mohamad AzmiAbdul Hamid Services to Pakistan (Malaysia) 13 Mr. Darren Sammy Services to Pakistan L4 Mr. Takamitsu Matsumura Literature (Japan) 15 Sheikh Ahmed bin Hamad AlKhalili Religious Scholar (Oman) V. SITARA.!.SHUJA,AT 16 Mr. Muhammad Bux Buriro Gallantry (Sindh) L7 Ms. Reshma Gallantry (Sindh) 18 Col. Shafi Ullah Khan Gallantry (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) VI. SITARA.I.IMTIAZ 19 Dr. Muhammad Masood ul Hassan Science (Physics) (Puniab) 20 Dr. Syed Hussain Abidi Science (Puniab) (lnd ustrial Biotech noloey) 2L Mr. -

Conferment of Awards

CONFIDENTIAL (NOT TO BE PUBLISHED/TRANSMITTED AND TELECASTED BEFORE 14.08.2020) F. No. 1/1/2020-Awards-I GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN CABINET SECRETARIAT (CABINET DIVISION) ***** PRESS RELEASE CONFERMENT OF PAKISTAN CIVIL AWARDS - 14Th AUGUST, 2020 On the occasion of Independence Day, 14th August, 2020, the President of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan has been pleased to confer the following 'Pakistan Civil Awards' on citizens of Pakistan as well as Foreign Nationals for showing excellence and courage in their respective fields. The investiture ceremony of these awards will take place on Pakistan Day, 23m March, 2021:- iiaL I. NISHAN-1-IMTIAZ 1 Mr. Sadeqain Naqvi Arts (Painting/Sculpture) 2 Prof. Shakir Ali Arts (Painting) 3 Mr. Zahoor ul Haq (Late) Arts (Painting/ Sculpture) 4 Ms. Abida Parveen Arts (Singing) 5 Dr. Jameel Jalibi Literature Muhammad Jameel Khan (Late) (Critic/Historian) (Sindh) 6 Mr. Ahmad Faraz (Late) Literature (Poetry) (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) II. HILAL-I-IMTIAZ 7 Prof. Dr. Anwar ul Hassan Gillani Science (Pharmaceutical (Sindh) Sciences) 8 Dr. Asif Mahmood Jah Public Service (Punjab) III. HILAL-I-OUAID-I-AZAM 9 Mr. Jack Ma Services to Pakistan (China) IV. SITARA-I-PAKISTAN 10 Mr. Kyu Jeong Lee Services to Pakistan (Korea) 11 Ms. Salma Ataullahjan Services to Pakistan (Canada) V. SITARA-I-SHUJA'AT 12 Mr. Jawwad Qamar Gallantry (Punjab) 13 Ms. Safia (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber Palchtunlchwa) 14 Mr. Hayatullah Gallantry (Khyber Palchttullthwa) 15 Malik Sardar Khan (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber PalchtunIchwa) 16 Mr. Mumtaz Khan Dawar (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber Palchtunkhwa) 17 Mr. Hayat Ullah Khan Dawar Hurmaz Gallantry (Shaheed) (Khyber PalchtunIchwa) 18 Malik Muhammad Niaz Khan (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber PalchtunIchwa) 19 Sepoy Akhtar Khan (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber PalchtunIchwa) 20 Mr. -

Vacation Work for Grade 3 Tasks for Engaging Students for the Month of April 2020 Social Studies

Ala-ud-Din Academy Girls High School (ALDA) Vacation Work for Grade 3 Tasks for Engaging Students For the Month of April 2020 Social Studies Project: National Traits of Pakistan Chapter # 1: Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah Chapter # 2: Celebrating Pakistan Days Chapter # 6: Allama Muhammad Iqbal Our National Poet Related questions, worksheet and video links are given below: Write answers of the following questions: Q # 1. What other title is given to Quaid-e-Azam? (Find answer on page # 1) Q # 2. What is the importance of the motto Quaid-e-Azam gives to us? (Find answer using internet) Q # 3. Write down the name of awards. (Find answer on page # 9) Q # 4. Why is Pakistan Day celebrated on 23rd March? (Find answer on page # 9) Q # 5. Write about history of Minar-e-Pakistan? (Find answer using internet) Q # 6. Write the name of books written by Allama Iqbal? (Find answer using internet) Q # 7. Explain Allama Iqbal Vision for the Muslims of India? (Find answer on page # 33) Page 1 of 3 WORKSHEET Q # 1: Write the names of these leaders and places. Write it on your notebook. Q # 2: Read Chapter #2; Celebrating Pakistan Day and fill in the blanks. Write it on notebook. On _________ day, national ____________ and medals are given by the __________ of Pakistan to ________ citizens who have achieved ____________ in their profession. Q # 3: Research and make a timeline of Allama Iqbal’s life. Write it on your notebook. Years 1877 1906 1908 1919 1930 1938 Events Q # 4: Write the answers by using internet. -

Board of Intermediate Education, Karachi Intermediate Examination, 2016 (Annual)

BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE EDUCATION, KARACHI INTERMEDIATE EXAMINATION, 2016 (ANNUAL) Date: 06.05.2016 PAKISTAN STUDIES (COMPULSORY) Max. Marks: 10 9:30 a.m. to 9:45 a.m. (Science, Home Economics & Medical Technology Groups) Time: 15 minutes SECTION ‘A’ The correct answers are (MULTIPLE CHOICE QUESTIONS) – (M.C.Qs.) highlighted in red colour. NOTE: i) This section consists of 20 part questions and all are to be answered. Write this Code No. in the Answerscript. Each question carries ½ mark. ii) Do not copy the part questions in your answerscript. Write only the answer in full against the proper number of the question and its part. iii) The code of your question paper is to be written in bold letters in the beginning of the answerscript. 1. Choose the correct answer for each from the given options: i) The Educational, scientific and cultural institution of the United Nations Organization is: * UNICEF * WHO * ILO * UNESCO ii) The constitutional head of Pakistan is the: * President * Prime Minister * Speaker, National Assembly * Chairman, Senate iii) The border shared between Pakistan and Afghanistan is called: * Durand line * Turkham line * Karakoram highway* Shahrah-e-Pakistan iv) This city of Pakistan is famous for its international seaport and airport: * Lahore * Karachi * Quetta * Islamabad v) Khilafat movement started in 1919 A.D. and ended in the year A.D.: * 1921 * 1922 * 1923 * 1924 vi) The All India Muslim League was founded under the leadership of: * Sir Syed Ahmed Khan * Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah * Nawab Saleemullah Khan * -

The Pakistan Society Newsletter January 2008

Newsletter - January 2011 Home Secretary and Minister for Women & DEC Pakistan Floods Appeal Equality Theresa May First Visit to Pakistan Raised £69 Million Fundraising for the DEC On 25 October 2010, Theresa May Pakistan Floods Appeal has arrived in Lahore for her first visit to now closed Pakistan as Home Secretary. She met with the Governor of Punjab, and the Chief Minister of The 13 DEC Member organisations will use Punjab and was given a cultural the £69 million to help the people affected by tour of Lahore Fort and Badshahi the flooding. The appeal is the DEC's third Mosque. The Home Secretary said most successful since the charity was set up “the UK and Pakistan are historic 45 years ago. Brendan Gormley, DEC Chief friends and the closest of partners. Executive, said the public response to the Whilst we must confront the floods has been "extraordinary". challenges that affect both our countries and wider regions, we The Pakistan Society Award 2010 can draw strength that our shared history and living family Gen Palmer, connections mean that we will face Chairman of them together.” The Pakistan In Islamabad, the Home Secretary met Mrs Yasmeen Rehman – the Prime Society Minister’s Adviser on Women’s Development. Theresa May said she was presented the encouraged by the work she saw to promote the valuable contribution award to Maj women make to Pakistani society. She supports legislation to criminalise Langlands on domestic violence, she said “this would send a strong political message that 25 September such abuse is unacceptable,” She added that the UK government works 2010 at a tirelessly to uphold the rights of all women in the UK and will not ban special wearing of the naqib or the burqha. -

Pakistan Independence Day 2021

AUGUST 14, 2021 TH 75 3 PAKISTAN INDEPENDENCE DAY August 14, 2021 Dr. Arif Alvi Imran Khan MESSAGE OF THE AmBASSADOR President Prime Minister extend heartiest felicitations to my Pakistani strong will to effectively counter affection that binds our two countries. brothers and sisters and our friends in the State of all challenges currently I greatly appreciate the excellent Qatar on the occasion of the 75th Independence confronting the country. This healthcare facilities and facilitation Day of Pakistan. This is a day to commemorate the includes the ongoing extended to the large Pakistani community Ifearless democratic struggle and countless sacrifices coronavirus crisis. Pakistan has during the coronavirus crisis. I am also rendered by the nation to achieve their right to have a received universal praise for its confident that the numbers of Pakistani homeland in accordance with their aspirations and effective policies. The workforce in Qatar will substantially distinct religious, cultural and social values. Economist magazine ranked increase in the longer term. Commemorating Independence Day in a befitting Pakistan among the best I take this opportunity to especially manner strengthens our resolve to work tirelessly performing countries for thank all overseas Pakistanis for their towards transforming our country in accordance with handling the pandemic. contribution to the development and the aspirations of the Father of the Nation Quaid-e- Measures taken by the prosperity of the country. For the Pakistani Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah and other leaders of the government to control the community in the State of Qatar, Independence struggle. spread of coronavirus, while Independence Day has always been an Today we pay homage to the Quaid-e-Azam by keeping the economy especially joyous occasion.