Notes and References

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neville Chamberlain's Announcement of the Introduction of Conscription To

FRANCO-BRITISH RELATIONS AND THE QUESTION OF CONSCRIPTION IN BRITAIN, 1938-1939 ABSTRACT - This article examines the relationship interaction between the French campaign for the introduction of British conscription during 1938-39 and the ebbs and flows of British public opinion on the same issue. In particular, it will demonstrate how French pressure for conscription varied in intensity depending on their perceptions of British opinion on the subject. It was this interaction between diplomatic and domestic pressures that ultimately compelled the British government to introduce conscription in April 1939. Furthermore, the issue of conscription also sheds light on the wider issue of Franco-British relations, revealing how French foreign policy was neither dictated by an ‘English Governess’ nor pursued independently of Great Britain. When Neville Chamberlain announced the introduction of conscription to the House of Commons on 26 April 1939 he not only reneged on previous promises but deviated from the traditional British aversion to peacetime compulsory service. Chamberlain defended himself by arguing that current international tensions could not be described as ‘peace-time in any sense in which the term could fairly be used’.1 Nonetheless, introducing conscription – albeit in a limited form2 – was alien to British tradition. How, therefore, can the decision be explained? What motivated the government to take such a step? This article sheds new light on the British decision to implement conscription in April 1939, moving beyond existing analyses by showing that the decision was motivated not only by a fusion of domestic and international pressures but by the interaction of the two. More specifically, contends that French pressure for British conscription ebbed and flowed in direct correlation to the French government’s perceptions of the British public’s attitude towards compulsory military service. -

Yalta, a Tripartite Negotiation to Form the Post-War World Order: Planning for the Conference, the Big Three’S Strategies

YALTA, A TRIPARTITE NEGOTIATION TO FORM THE POST-WAR WORLD ORDER: PLANNING FOR THE CONFERENCE, THE BIG THREE’S STRATEGIES Matthew M. Grossberg Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Department of History, Indiana University August 2015 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Master’s Thesis Committee ______________________________ Kevin Cramer, Ph. D., Chair ______________________________ Michael Snodgrass, Ph. D. ______________________________ Monroe Little, Ph. D. ii ©2015 Matthew M. Grossberg iii Acknowledgements This work would not have been possible without the participation and assistance of so many of the History Department at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis. Their contributions are greatly appreciated and sincerely acknowledged. However, I would like to express my deepest appreciation to the following: Dr. Anita Morgan, Dr. Nancy Robertson, and Dr. Eric Lindseth who rekindled my love of history and provided me the push I needed to embark on this project. Dr. Elizabeth Monroe and Dr. Robert Barrows for being confidants I could always turn to when this project became overwhelming. Special recognition goes to my committee Dr. Monroe Little and Dr. Michael Snodgrass. Both men provided me assistance upon and beyond the call of duty. Dr. Snodgrass patiently worked with me throughout my time at IUPUI, helping my writing progress immensely. Dr. Little came in at the last minute, saving me from a fate worse than death, another six months of grad school. Most importantly, all credit is due Dr. -

Sir Horace Wilson and Appeasement*

The Historical Journal, 53, 4 (2010), pp. 983–1014 f Cambridge University Press 2010 doi:10.1017/S0018246X10000270 SIR HORACE WILSON AND APPEASEMENT* G. C. P E D E N University of Stirling ABSTRACT. Sir Horace Wilson was Neville Chamberlain’s confidential adviser while the latter was prime minister. The article addresses three questions. First, what was Wilson’s role in Whitehall in connection with rearmament and foreign policy? Second, did he diminish the influence of the Foreign Office? Third, what contribution does his defence of appeasement make to understanding of a subject that continues to divide historians? The article concludes that Wilson played an important role in enabling Chamberlain to pursue his foreign policy goals. However, when there was outright disagreement between Wilson and the Foreign Office, it was the Foreign Office view that prevailed. Finally, the evidence of Wilson’s words and actions, both in 1937–9 and later, broadly supports R. A. C. Parker’s post-revisionist interpretation of appeasement, particularly as regards Munich, but Wilson was a good deal firmer in 1939 about Britain’s will to fight, if necessary, than his critics then or later allowed. No history of British appeasement is complete without some reference to Sir Horace Wilson’s role as Neville Chamberlain’s confidential adviser, and in particular to Wilson’s meetings with Hitler as the prime minister’s emissary im- mediately prior to the Munich conference in September 1938. Yet there has been no serious study of Wilson himself in relation to appeasement since Martin Gilbert published a short article in History Today in 1982.1 To date, archival work on Wilson’s career has been confined to his years at the Ministry of Labour and the Board of Trade.2 This neglect would have surprised Wilson’s contemporaries. -

H-Diplo Roundtable XXII-1 on Gabriel Gorodetsky, Ed. the Complete Maisky Diaries, Volumes I-III

H-Diplo H-Diplo Roundtable XXII-1 on Gabriel Gorodetsky, ed. The Complete Maisky Diaries, Volumes I-III Discussion published by George Fujii on Monday, September 7, 2020 H-Diplo Roundtable XXII-1 Gabriel Gorodetsky, ed. The Complete Maisky Diaries, Volumes I-III. Translated by Tatiana Sorokina and Oliver Ready. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017. ISBN: 9780300117820 (hardcover, $300.00). 7 September 2020 | https://hdiplo.org/to/RT22-1 Editor: Diane Labrosse | Production Editor: George Fujii Contents Introduction by Warren Kimball, Rutgers University. 2 Review by Anne Deighton, University of Oxford. 7 Review by Norman Naimark, Stanford University. 10 Review by Vladimir Pechatnov, Moscow State Institute of International Relations. 13 Review by Alexis Peri, Boston University. 16 Review by Sergey Radchenko, Cardiff University. 21 Response by Gabriel Gorodetsky, Tel Aviv University and All Souls College, University of Oxford. 26 Introduction by Warren Kimball, Rutgers University As a friend once commented about a review of edited documents: “An incise, pithy review that highlights what everyone wishes to know about the collection, and can take away from the texts. Little nuggets about the drafts of history that never really blow in the conference window are the big story here.”[1] What is This Genre? In books like this, attaching ‘editor (ed.)’ after the name of the ‘author’ is misleading since the author is the one who wrote the diaries; in this case, Ivan Mikhailovich Maisky (Jan Lachowiecki), a Soviet- era diplomat who spent eleven years (1932-1943) in London as Joseph Stalin’s Ambassador to Great Britain. But gathering or compiling documents is not the same as what Gabriel Gorodetsky has done Citation: George Fujii. -

A History of Global Governance

2 A History of Global Governance It is the sense of Congress that it should be a fundamental objective of the foreign policy of the United States to support and strengthen the United Nations and to seek its development into a world federation open to all nations with definite and limited powers adequate to preserve peace and prevent aggression through the enactment, interpretation and enforcement of world law. House Concurrent Resolution 64, 1949, with 111 co-sponsors There are causes, but only a very few, for which it is worthwhile to fight; but whatever the cause, and however justifiable the war, war brings about such great evils that it is of immense importance to find ways short of war in which the things worth fighting for can be secured. I think it is worthwhile to fight to prevent England and America being conquered by the Nazis, but it would be far better if this end could be secured without war. For this, two things are necessary. First, the creation of an international government, possessing a monopoly of armed force, and guaranteeing freedom from aggression to every country; second, that wars (other than civil wars) are justified when, and only when, they are fought in defense of the international law established by the international authority. Wars will cease when, and only when, it becomes evident beyond reasonable doubt that in any war the aggressor will be defeated. 1 Bertrand Russell, “The Future of Pacifism” By the end of the 20th century, if not well before, humankind had come to accept the need for and the importance of various national institutions to secure political stability and economic prosperity. -

Churchill's Diplomatic Eavesdropping and Secret Signals Intelligence As

CHURCHILL’S DIPLOMATIC EAVESDROPPING AND SECRET SIGNALS INTELLIGENCE AS AN INSTRUMENT OF BRITISH FOREIGN POLICY, 1941-1944: THE CASE OF TURKEY Submitted for the Degree of Ph.D. Department of History University College London by ROBIN DENNISTON M.A. (Oxon) M.Sc. (Edin) ProQuest Number: 10106668 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10106668 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 2 ABSTRACT Churchill's interest in secret signals intelligence (sigint) is now common knowledge, but his use of intercepted diplomatic telegrams (bjs) in World War Two has only become apparent with the release in 1994 of his regular supply of Ultra, the DIR/C Archive. Churchill proves to have been a voracious reader of diplomatic intercepts from 1941-44, and used them as part of his communication with the Foreign Office. This thesis establishes the value of these intercepts (particularly those Turkey- sourced) in supplying Churchill and the Foreign Office with authentic information on neutrals' response to the war in Europe, and analyses the way Churchill used them. -

The Anschluss Movement and British Policy

THE ANSCHLUSS MOVEMENT AND BRITISH POLICY: MAY 1937 - MARCH 1938 by Elizabeth A. Tarte, A.B. A 'l11esis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Part ial Fulfillment of the Re quirements f or the Degree of Master of Arts Milwaukee, Wisconsin May, 1967 i1 PREFACE For many centuri.es Austria. bad been closely eom'lect E!d \'lieh the German states. 111 language and eulture. Austri.a and Germany had always looked to each other. AS late as the t~tentieth century. Austria .st111 clung to her traditional leadership in Germany . In the perlod following the First World War, Austria continued to lo(!)k to Germany for leadership. Aus tria, beset by numerous economic and social problems. made many pleas for uni on with her German neighbor. From 1919 to 1933 all ;novas on the part of Austria and Germany for union, -v.71\ether political oreeon01;n1c. were th"larted by the signatories of the pea.ce treaties. Wl ,th the entrance of Adolf Hitler onto the European political stage, the movement fQr the Anschluss .. - the union of Germany and Austria .- t ook on a different light. Austrians no longer sought \.Ulion with a Germany v.ilich was dominated by Hitler. The net"l National $Gclalist Gertna,n Reich aimed at: the early acq'U1Si ,tiQn of Austria. The latter "(vas i mportant to the lteich fGr its agricultural and Batural reSources and would i mprove its geopolitical and military position in Europe. In 1934 the National Soci aU.sts assaSSinated Dr .. U.:. £tlto1bot''t Pollfuas, the Aust~i ..\n Cbaneellot'l in ,an 8.'ttcmp't to tillkltl c:ronet:Ql or his: eountry. -

Summit Diplomacy: Some Lessons from History for 21St Century Leaders Transcript

Summit Diplomacy: Some Lessons from History for 21st Century Leaders Transcript Date: Tuesday, 4 June 2013 - 6:00PM Location: Barnard's Inn Hall 4 June 2013 Summit Diplomacy: Some Lessons From History For 21st Century Leaders David Reynolds This is the first of a series of three lectures about history and policy, about the ways in which historians might be able to contribute to current policy debates. Tonight, I am talking about diplomacy; next week, there will be something about environmental policy; and then, thirdly, about development policy, and that is an example of what history and policy is trying to do: link up academic research with issues of current concern in the political arena. Some lessons from history, “lessons” in quotation marks because, as you will see, I am wary about the use of the term “lessons” or I think at least we have to be clear what history can teach and what it cannot teach… Here we are, statesmen on the world stage. There is Winston Churchill in Washington in 1941, and there is David Cameron and Barack Obama at the G20 Summit in Toronto, a year or so ago I think – example, the G20, of how summitry has become institutionalised in the last 60 years, and that is something I will get onto in a moment. The idea of a summit meeting is now very much very familiar to us. There is Time magazine from the 1980s, from 1985, “Let’s Talk”, Reagan and Gorbachev. This summitry is about top level meetings for high stakes. What I want to suggest to you is that, despite all that media attention about something special to do with summitry, it is rooted in daily life. -

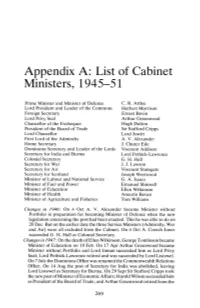

Appendix A: List of Cabinet Ministers, 1945-51

Appendix A: List of Cabinet Ministers, 1945-51 Prime Minister and Minister of Defence C. R. Attlee Lord President and Leader of the Commons Herbert Morrison Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin Lord Privy Seal Arthur Greenwood Chancellor of the Exchequer Hugh Dalton President of the Board of Trade Sir Stafford Cripps Lord Chancellor Lord Jowitt First Lord of the Admiralty A. V. Alexander Home Secretary J. Chuter Ede Dominions Secretary and Leader of the Lords Viscount Addison Secretary for India and Burma Lord Pethick-Lawrence Colonial Secretary G. H. Hall Secretary for War J. J. Lawson Secretary for Air Viscount Stansgate Secretary for Scotland Joseph Westwood Minister of Labour and National Service G. A. Isaacs Minister of Fuel and Power Emanuel Shinwell Minister of Education Ellen Wilkinson Minister of Health Aneurin Bevan Minister of Agriculture and Fisheries Tom Williams Changes in 1946: On 4 Oct A. V. Alexander became Minister without Portfolio in preparation for becoming Minister of Defence when the new legislation concerning the post had been enacted. This he was able to do on 20 Dec. But on the earlier date the three Service Ministers (Admiralty, War and Air) were all excluded from the Cabinet. On 4 Oct A. Creech Jones succeeded G. H. Hall as Colonial Secretary. Changes in 1947: On the death of Ellen Wilkinson, George Tomlinson became Minister of Education on 10 Feb. On 17 Apr Arthur Greenwood became Minister without Portfolio and Lord Inman succeeded him as Lord Privy Seal; Lord Pethick-Lawrence retired and was succeeded by Lord Listowel. On 7 July the Dominions Office was renamed the Commonwealth Relations Office. -

The Role of Rhetoric in Anglo-French Imperial Relations, 1940-1945

1 Between Policy Making and the Public Sphere: The Role of Rhetoric in Anglo-French Imperial Relations, 1940-1945 Submitted by Rachel Renee Chin to the University of Exeter As a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History In September 2016 This thesis is available for library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other university. Signature: 2 Abstract The long history of Anglo-French relations has often been acrimonious. After the German defeat of France in June 1940 the right to represent the French nation was contested by Philippe Pétain’s Vichy government and Charles de Gualle’s London-based Free French resistance movement. This thesis will examine the highly complex relationship between Britain and these two competing sources of Frenchness between 1940 and 1945. It will do so through a series of empire-themed “crisis points,” which contributed to a heightened state of Anglo-French tension affecting all three actors. This study uses rhetoric as a means to link decision makers or statesman to the public sphere. It argues that policy makers, whether in the British War Cabinet, de Gaulle’s headquarters at Carlton Gardens, or Pétain’s ministries at Vichy anticipated how their policies were likely to be received by a group or groups of individuals. -

HAROLD MACMILLAN's APPOINTMENT AS MINISTER at ALGIERS, 1942: the Military, Political, and Diplomatic Background1

HAROLD MACMILLAN'S APPOINTMENT AS MINISTER AT ALGIERS, 1942: The Military, Political, and Diplomatic Background1 BY SYDNEY H. ZEBEL Mr. Zebel is a professor at Rutgers University, Newark N THE autumn of 1942, Allied forces operating under Dwight Eisenhower's direction invaded French North Africa. Because of Iunanticipated developments, the American general and his military and political advisers found themselves cooperating closely with Ad- miral Jean Darlan and other reputedly fascist officials2—this in seem- ingly flagrant disregard of the idealistic war aims announced in the Atlantic Charter and the Declaration of the United Nations. The reac- tion to this strange and distasteful collaboration was a public uproar in liberal circles in the United States and a greater, more general, and more sustained wave of protest in Britain. British cabinet ministers, for moral and less altruistic reasons, likewise expressed their deep concern. Dissatisfaction was most profound among those dissident Frenchmen, notably General Charles de Gaulle, who remained at war against the Axis. Then, about six weeks later, the public indignation subsided when Darlan was replaced by a more reputable but ineffectual leader, General Henri Giraud. But the diplomatic controversies which had erupted over North African policies were not really eased until Washington agreed to the appointment of the future Prime Minister Harold Macmillan as the new British representative at Eisenhower's headquarters to share more fully in the political decision-making with the Americans. I. The invasion of Vichy-controlled North Africa was first considered at the Washington ( Arcadia) conference between President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill in December, 1941. -

The Anglo-American ‘Special Relationship’ During the Second World War: a Selective Guide to Materials in the British Library

THE BRITISH LIBRARY THE ANGLO-AMERICAN ‘SPECIAL RELATIONSHIP’ DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR: A SELECTIVE GUIDE TO MATERIALS IN THE BRITISH LIBRARY by ANNE SHARP WELLS THE ECCLES CENTRE FOR AMERICAN STUDIES INTRODUCTION I. BIBLIOGRAPHIES, REFERENCE WORKS AND GENERAL STUDIES A. BIBLIOGRAPHICAL WORKS B. BIOGRAPHICAL DICTIONARIES C. ATLASES D. REFERENCE WORKS E. GENERAL STUDIES II. ANGLO-AMERICAN RELATIONSHIP A. GENERAL WORKS B. CHURCHILL AND ROOSEVELT [SEE ALSO III.B.2. WINSTON S. CHURCHILL; IV.B.1. FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT] C. CONFERENCES AND DECLARATIONS D. MILITARY 1. GENERAL WORKS 2. LEND-LEASE AND LOGISTICS 3. STRATEGY E. INTELLIGENCE F. ECONOMY AND RAW MATERIALS G. SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 1. GENERAL STUDIES 2. ATOMIC ENERGY H. PUBLIC OPINION, PROPAGANDA AND MEDIA I. HOLOCAUST [SEE ALSO VI.C. MIDDLE EAST] III. UNITED KINGDOM A. GENERAL WORKS B. PRIME MINISTERS 1. NEVILLE CHAMBERLAIN 2. WINSTON S. CHURCHILL [SEE ALSO II.B. CHURCHILL AND ROOSEVELT] 3. CLEMENT R. ATTLEE C. GOVERNMENT, EXCLUDING MILITARY 1. MISCELLANEOUS STUDIES 2. ANTHONY EDEN 3. PHILIP HENRY KERR (LORD LOTHIAN) 4. EDWARD FREDERICK LINDLEY WOOD (EARL OF HALIFAX) D. MILITARY IV. UNITED STATES A. GENERAL WORKS B. PRESIDENTS 1. FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT [SEE ALSO II.B. CHURCHILL AND ROOSEVELT] 2. HARRY S. TRUMAN C. GOVERNMENT, EXCLUDING MILITARY 1. MISCELLANEOUS WORKS 2. JAMES F. BYRNES 3. CORDELL HULL 4. W. AVERELL HARRIMAN 5. HARRY HOPKINS 6. JOSEPH P. KENNEDY 7. EDWARD R. STETTINIUS 8. SUMNER WELLES 9. JOHN G. WINANT D. MILITARY 1. GENERAL WORKS 2. CIVILIAN ADMINISTRATION 3. OFFICERS a. MISCELLANEOUS STUDIES b. GEORGE C. MARSHALL c. DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER E.