The Future of the Iraqi Kurds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iraq's Democratic Dilemmas: from Entrenched Dictatorship to Fragile

Information, Society and Justice, Volume 3 No. 2, July 2010: pp 107-115 ISSN 1756-1078 Iraq’s democratic dilemmas: from entrenched dictatorship to fragile democracy Namo Abdulla1 Abstract The US-led allied invasion of Iraq in 2003 toppled Iraq’s long ruling dictator, Saddam Hussein, promising to import democracy to a country whose history had been shaped by both religious and secular totalitarianism. Lack of deep-understanding of the Iraq’s culture had led to the former US administration to equate the demise of Saddam with the demise of totalitarianism. The presence of Saddam was a great obstacle of democracy, but his removal changed little. Saddam and his former like-minded people created a culture capable of producing as many dictators as it wants. This essay argues that Iraq’s political culture is highly undemocratic; and thus the future of democracy in the country is bleak. It proves so by highlighting the most important incompatible elements of Iraq’s culture with democracy. Keyword Democracy, oligarchy, political elites, authoritarianism, power, globalization, Islam, ethno-nationalism, Iraq Introduction This paper examines the dilemmas of democratic development in Iraq, particularly in the aftermaths of US and allied invasion of the country (2003 to present). Iraqi is often described as a country where democracy does not work: “Iraq has never had a genuine democracy in its modern history’ (Basham, 2004: 2). Why? Is it because democracy is a foreign concept to Iraq’s culture and society? If so, is there the problem with the concept ‘democracy’ as a child of the West, which cannot suit every culture or the vice-versa? To what extent does the diversity of the Iraqi society make it difficult for democracy to take root? Is Islam, as a religion of an overwhelming majority of the Iraqis, to be blamed for the incapability of Iraq to boast democracy? If so, then how? This essay tries to provide 1 Namo Abdulla is a freelance journalist based in Erbil, the capital of Iraqi Kurdistan. -

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

Perceptual Dialectology and GIS in Kurdish 1

Perceptual Dialectology and GIS in Kurdish 1 Full title: A perceptual dialectological approach to linguistic variation and spatial analysis of Kurdish varieties Main Author: Eva Eppler, PhD, RCSLT, Mag. Phil Reader/Associate Professor in Linguistics Department of Media, Culture and Language University of Roehampton | London | SW15 5SL [email protected] | www.roehampton.ac.uk Tel: +44 (0) 20 8392 3791 Co-author: Josef Benedikt, PhD, Mag.rer.nat. Independent Scholar, Senior GIS Researcher GeoLogic Dr. Benedikt Roegergasse 11/18 1090 Vienna, Austria [email protected] | www.geologic.at Short Title: Perceptual Dialectology and GIS in Kurdish Perceptual Dialectology and GIS in Kurdish 2 Abstract: This paper presents results of a first investigation into Kurdish linguistic varieties and their spatial distribution. Kurdish dialects are used across five nation states in the Middle East and only one, Sorani, has official status in one of them. The study employs the ‘draw-a-map task’ established in Perceptual Dialectology; the analysis is supported by Geographical Information Systems (GIS). The results show that, despite the geolinguistic and geopolitical situation, Kurdish respondents have good knowledge of the main varieties of their language (Kurmanji, Sorani and the related variety Zazaki) and where to localize them. Awareness of the more diverse Southern Kurdish varieties is less definitive. This indicates that the Kurdish language plays a role in identity formation, but also that smaller isolated varieties are not only endangered in terms of speakers, but also in terms of their representations in Kurds’ mental maps of the linguistic landscape they live in. Acknowledgments: This work was supported by a Santander and by Ede & Ravenscroft Research grant 2016. -

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq Julie Ahn—Maeve Campbell—Pete Knoetgen Client: Office of Iraq Affairs, U.S. Department of State Harvard Kennedy School Faculty Advisor: Meghan O’Sullivan Policy Analysis Exercise Seminar Leader: Matthew Bunn May 7, 2018 This Policy Analysis Exercise reflects the views of the authors and should not be viewed as representing the views of the US Government, nor those of Harvard University or any of its faculty. Acknowledgements We would like to express our gratitude to the many people who helped us throughout the development, research, and drafting of this report. Our field work in Iraq would not have been possible without the help of Sherzad Khidhir. His willingness to connect us with in-country stakeholders significantly contributed to the breadth of our interviews. Those interviews were made possible by our fantastic translators, Lezan, Ehsan, and Younis, who ensured that we could capture critical information and the nuance of discussions. We also greatly appreciated the willingness of U.S. State Department officials, the soldiers of Operation Inherent Resolve, and our many other interview participants to provide us with their time and insights. Thanks to their assistance, we were able to gain a better grasp of this immensely complex topic. Throughout our research, we benefitted from consultations with numerous Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) faculty, as well as with individuals from the larger Harvard community. We would especially like to thank Harvard Business School Professor Kristin Fabbe and Razzaq al-Saiedi from the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative who both provided critical support to our project. -

Research Notes

RESEARCH NOTES The Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ No. 38 ■ Oc t ober 2016 How to Secure Mosul Lessons from 2008—2014 MICHAEL KNIGHTS N EARLY 2017, Iraqi security forces (ISF) are likely to liberate Mosul from Islamic State control. But given the dramatic comebacks staged by the Islamic State and its predecessors in the city in I2004, 2007, and 2014, one can justifiably ask what will stop IS or a similar movement from lying low, regenerating, and wiping away the costly gains of the current war. This paper aims to fill an important gap in the literature on Mosul, the capital of Ninawa province, by looking closely at the underexplored issue of security arrangements for the city after its liberation, in particular how security forces should be structured and controlled to prevent an IS recurrence. Though “big picture” politi- cal deals over Mosul’s future may ultimately be decisive, the first priority of the Iraqi-international coalition is to secure Mosul. As John Paul Vann, a U.S. military advisor in Vietnam, noted decades ago: “Security may be ten percent of the problem, or it may be ninety percent, but whichever it is, it’s the first ten percent or the first ninety percent. Without security, nothing else we do will last.”1 This study focuses on two distinct periods of Mosul’s Explanations for both the 2007–2011 successes and recent history. In 2007–2011, the U.S.-backed Iraqi the failures of 2011–2014 are easily identified. In the security forces achieved significant success, reducing earlier span, Baghdad committed to Mosul’s stabilization security incidents in the city from a high point of 666 and Iraq’s prime minister focused on the issue, authoriz- per month in the first quarter of 2008 to an average ing compromises such as partial amnesty and a reopen- of 32 incidents in the first quarter of 2011. -

The Yazidis Perceptions of Reconciliation and Conflict

The Yazidis Perceptions of Reconciliation and Conflict Dave van Zoonen Khogir Wirya About MERI The Middle East Research Institute engages in policy issues contributing to the process of state building and democratisation in the Middle East. Through independent analysis and policy debates, our research aims to promote and develop good governance, human rights, rule of law and social and economic prosperity in the region. It was established in 2014 as an independent, not-for-profit organisation based in Erbil, Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Middle East Research Institute 1186 Dream City Erbil, Kurdistan Region of Iraq T: +964 (0)662649690 E: [email protected] www.meri-k.org NGO registration number. K843 © Middle East Research Institute, 2017 The opinions expressed in this publication are the responsibility of the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of MERI, the copyright holder. Please direct all enquiries to the publisher. The Yazidis Perceptions of Reconciliation and Conflict MERI Policy Paper Dave van Zoonen Khogir Wirya October 2017 1 Contents 1. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................4 2. “Reconciliation” after genocide .........................................................................................................5 -

Fighting-For-Kurdistan.Pdf

Fighting for Kurdistan? Assessing the nature and functions of the Peshmerga in Iraq CRU Report Feike Fliervoet Fighting for Kurdistan? Assessing the nature and functions of the Peshmerga in Iraq Feike Fliervoet CRU Report March 2018 March 2018 © Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’. Cover photo: Peshmerga, Kurdish Army © Flickr / Kurdishstruggle Unauthorized use of any materials violates copyright, trademark and / or other laws. Should a user download material from the website or any other source related to the Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’, or the Clingendael Institute, for personal or non-commercial use, the user must retain all copyright, trademark or other similar notices contained in the original material or on any copies of this material. Material on the website of the Clingendael Institute may be reproduced or publicly displayed, distributed or used for any public and non-commercial purposes, but only by mentioning the Clingendael Institute as its source. Permission is required to use the logo of the Clingendael Institute. This can be obtained by contacting the Communication desk of the Clingendael Institute ([email protected]). The following web link activities are prohibited by the Clingendael Institute and may present trademark and copyright infringement issues: links that involve unauthorized use of our logo, framing, inline links, or metatags, as well as hyperlinks or a form of link disguising the URL. About the author Feike Fliervoet is a Visiting Research Fellow at Clingendael’s Conflict Research Unit where she contributes to the Levant research programme, a three year long project that seeks to identify the origins and functions of hybrid security arrangements and their influence on state performance and development. -

Measuring Security and Stability in Iraq

MMMeeeaaasssuuurrriiinnnggg SSStttaaabbbiiillliiitttyyy aaannnddd SSSeeecccuuurrriiittyyy iiinnn IIIrrraaaqqq December 2007 Report to Congress In accordance with the Department of Defense Appropriations Act 2007 (Section 9010, Public Law 109-289) Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... iii 1. Stability and Security in Iraq .................................................................................................1 1.1. Political Stability......................................................................................................1 National Reconciliation...........................................................................................1 Political Commitments.............................................................................................1 Government Reform ................................................................................................3 Transnational Issues.................................................................................................5 1.2. Economic Activity...................................................................................................8 Budget Execution.....................................................................................................8 IMF Stand-By Arrangement and Debt Relief..........................................................9 Indicators of Economic Activity..............................................................................9 -

Between Ankara and Tehran: How the Scramble for Kurdistan Can Reshape Regional Relations

Between Ankara and Tehran: How the Scramble for Kurdistan Can Reshape Regional Relations Micha’el Tanchum On June 30, 2014, President Masoud Barzani of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) made the historic announcement that he would seek a formal referendum on Kurdish independence. Barzani’s announcement came after the June 2014 advance into northern Iraq by the jihadist forces of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) had effectively eliminated Iraqi government control over the provinces bordering the KRG. As Iraq’s army abandoned its positions north of Baghdad, the KRG’s Peshmerga advanced into the “disputed territories” beyond the KRG’s formal boundaries and took control of the oil-rich city of Kirkuk, the jewel in the crown of Iraqi Kurdish territorial ambitions. Thus, the Barzani-led KRG calculated it had attained the necessary political and economic conditions to contemplate outright independence. Asserting Iraq had been effectively “partitioned” and that “conditions are right,” the KRG President declared, “From now on, we will not hide that the goal of Kurdistan is independence.” 1 The viability of an independent Kurdish state will ultimately depend on the Barzani government’s ability to recalibrate its relations with its two powerful neighbors, Turkey and Iran. This, in turn, depends on the ability of Barzani’s Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP) to preserve its hegemony over Iraqi Kurdistan in the face of challenges posed by its Iraqi political rival, the PUK (Patriotic Union of Kurdistan), and the Turkish-based PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party). Barzani’s objective to preserve the KDP’s authority from these threats forms one of the main drivers behind his Dr. -

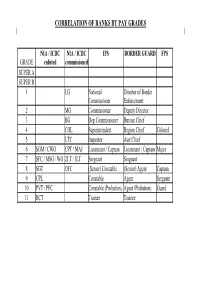

Security Salary Matrix (.Pdf)

CORRELATION OF RANKS BY PAY GRADES NIA / ICDC NIA / ICDC IPS BORDER GUARDFPS GRADE enlisted commissioned SUPER A SUPER B 1 LG National Director of Border Commissioner Enforcement 2 MG Commissioner Deputy Director 3 BG Dep Commissioner Bureau Chief 4 COL Superintendent Region Chief Colonel 5 LTC Inspector Asst Chief 6 SGM / CWO CPT / MAJ Lieutenant / Captain Lieutenant / Captain Major 7 SFC / MSG / WO 2LT / 1LT Sergeant Sergeant 8 SGT OFC (Senior) Constable (Senior) Agent Captain 9 CPL Constable Agent Sergeant 10 PVT / PFC Constable (Probation) Agent (Probation) Guard 11 RCT Trainee Trainee COMPARISON OF RANKS (SHOWING INITIAL STEP INCREMENT) NIA / ICDC NIA / ICDC IPS BORDER FPS GRADE enlisted commissioned SUPER A SUPER B National Dir of Border 1 LG Commissioner Enforcement 1 1 1 2 MG Commissioner Deputy Director 1 1 1 Dep 3 BG Commissioner Bureau Chief 1 1 1 4 COL Superintendent Region Chief Colonel 1 1 1 1 5 LTC Inspector Asst Chief 1 1 1 6 SGM / CWO CAPT/MAJ Lieut / Captain Lieut / Captain Major 1 2 1 6 1 6 1 6 1 7 SFC/MSG/WO 2LT / 1LT Sergeant Sergeant 4 7 8 6 7 6 6 8 SGT OFC (Snr) Constable (Snr) Agent Captain 6 8 6 6 1 9 CPL Constable Agent Sergeant 7 5 5 1 10 PVT / PFC Constable (Probation) Agent (Probation) Guard 4 8 4 4 1 11 Recruit Trainee Trainee 1 4 4 ENTRY LEVEL SALARIES FOR NEW IRAQI ARMY / IRAQI CIVIL DEFENCE CORPS STEPS- SALARIES LISTED IN NEW IRAQI DINAR Grade Enlisted Commission 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 LG 740,000 760,000 780,000 80,0000 820,000 840,000 860,000 880,000 2 MG 574,000 589,000 605,000 620,000 636,000 651,000 -

Why Is the World So Unsettled?

www.csbaonline.org 1 Why Is the World So Unsettled? The End of the Post-Cold War Era and the Crisis of Global Order The essence of a revolution is that it appears to contemporaries as a series of more or less unrelated upheavals. The temptation is great to treat each issue as an immediate and isolated problem which once surmounted will permit the fundamental stability of the international order to reassert itself. But the crises which form the headlines of the day are symptoms of deep-seated structural problems. --Henry Kissinger, 19691 During Donald Trump’s presidency and after, both U.S. foreign policy and the international system are likely to be wracked by crises. The instability and violence caused by a militarily resurgent Russia’s aggressive behavior in Ukraine and elsewhere; the growing frictions and threat of conflict with an increasingly assertive China; the provocations of an insecure and progressively more dangerous North Korea; the profound Middle Eastern instability generated by a revolutionary, revisionist Iran as well as by persistent challenges from non-state actors—these and other challenges have tested U.S. officials and the basic stability of international affairs in recent years, and they are likely to do so for the foreseeable future. The world now seems less stable and more perilous than at any time since the Cold War; both the number and severity of today’s global crises are on the rise. Yet as Henry Kissinger wrote nearly a half-century ago, during another time of great upheaval in the international environment, making sense of crises requires doing more than simply viewing them—or seeking to address them—individually, for all are symptomatic of deeper changes in the structure of international relations. -

UNCLASSIFIED � Ll 67

UNCLASSIFIED Ll 67 ' ; RELEASED IN FULL SFRC hearing "Iraq: the way ahead" Publication: FNS-Transcript Wire Service Date: 05/18/2004 HEARING OF THE SENATE FOREIGN RELATIONS COMMITTEE SUBJECT: "IRAQ: THE WAY AHEAD" CHAIRED BY: SENATOR RICHARD LUGAR (R-IN) WITNESSES: DEPUTY SECRETARY OF STATE RICHARD ARMITAGE; DEPUTY SECRETARY OF DEFENSE PAUL WOLFOWITZ; AND LIEUTENANT GENERAL WALTER SHARP, DIRECTOR, STRATEGIC PLANS AND POLICY, JOINT CHIEFS OF STAFF 106 DIRKSEN SENATE OFFICE BUILDING, WASHINGTON, 1).C. 9:33 A.M. EDT, TUESDAY. MAY 18. 2004 Copyright ©2004 by Federal News Service, Inc., %lite 220. 1919 M St. NW, Washington, DC, 20036, USA. Federal News Service is a private firm not of with the federal government. No portion of this transcript may be copied, sold or retransmitted without the written authority of Federal News Service. Inc. Copyright is not claimed as to any part of the original work prepared by a United States government officer or employee as a part of that person'sofficial d For information on subscribing to the FNS Internet Service at www.fednews.com , please email lack Graeme at [email protected] or call 1-800-211-402' SEN. LUGAR: (Sounds gavel.) This hearing of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee is called to order. Today the Committee on Foreign Relations meets to continue our ongoing oversight of American policy toward Iraq. The coalition intends to hand over sovereignty to an Iraqi government six weeks from tomorrow. We're pleased to welcome Mr. Richard Armitage, deputy secretary of State; Mr. Paul Wolfowitz, deputy secretary of Defense; Lieutenant General Walter Sharp, director of strategic plans and policy for the Joint Chiefs of Staff.