Conscientization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Commitment to Black Lives

Our Commitment to Black Lives June 3, 2020 Dear Friends of the CCE, We are writing today to affirm that we, the staff of the Center for Community Engagement, believe and know that Black Lives Matter. We honor wide-spread grief for the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery among the many named and unnamed Black lives lost to racial violence and hatred in the United States. The Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement — co-founded by Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi — arose to address ongoing legacies of racialized violence in our country. As BLM leaders have consistently stated, disproportionate violence toward Black communities by law enforcement is one manifestation of anti-Black systemic racism perpetuated across public and private institutions including health care, housing and education. We are firmly and deeply committed to the lives of Black community members, Black youth and their families, and Seattle U’s Black students, faculty and staff. We believe that messages like this one can have an impact, and yet our words ring hollow without action. The Center for Community Engagement is committed to becoming an anti-racist organization. Fulfilling our mission of connecting campus and community requires long-term individual, organizational, and system-wide focus on understanding and undoing white supremacy. We see our commitment to anti-racism as directly linked to Seattle University’s pursuit of a more just and humane world as well as our Jesuit Catholic ethos of cura personalis, care for the whole person. We urge you to participate in ways that speak to you during the national racial crisis that is continuing to unfold. -

A Herstory of the #Blacklivesmatter Movement by Alicia Garza

A Herstory of the #BlackLivesMatter Movement by Alicia Garza From The Feminist Wire, October 7, 2014 I created #BlackLivesMatter with Patrisse Cullors and Opal Tometi, two of my sisters, as a call to action for Black people after 17-year-old Trayvon Martin was post-humously placed on trial for his own murder and the killer, George Zimmerman, was not held accountable for the crime he committed. It was a response to the anti-Black racism that permeates our society and also, unfortunately, our movements. Black Lives Matter is an ideological and political intervention in a world where Black lives are systematically and intentionally targeted for demise. It is an affirmation of Black folks’ contributions to this society, our humanity, and our resilience in the face of deadly oppression. We were humbled when cultural workers, artists, designers and techies offered their labor and love to expand #BlackLivesMatter beyond a social media hashtag. Opal, Patrisse, and I created the infrastructure for this movement project—moving the hashtag from social media to the streets. Our team grew through a very successful Black Lives Matter ride, led and designed by Patrisse Cullors and Darnell L. Moore, organized to support the movement that is growing in St. Louis, MO, after 18-year old Mike Brown was killed at the hands of Ferguson Police Officer Darren Wilson. We’ve hosted national conference calls focused on issues of critical importance to Black people working hard for the liberation of our people. We’ve connected people across the country working to end the various forms of injustice impacting our people. -

Applicant V. DERAY MCKESSON; BLACK LIVES MATTER; BLACK LIVES MATTER NETWORK, INCORPORATED Defendants - Respondents

STATE OF LOUISIANA 2021-CQ-00929 LOUISIANA SUPREME COURT OFFICER JOHN DOE, Police Officer Plaintiff - Applicant v. DERAY MCKESSON; BLACK LIVES MATTER; BLACK LIVES MATTER NETWORK, INCORPORATED Defendants - Respondents OFFICER JOHN DOE Plaintiff - Applicant Versus DeRAY McKESSON; BLACK LIVES MATTER; BLACK LIVES MATTER NETWORK, INCORPORATED Defendants - Respondents On Certified Question from the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit No. 17-30864 Circuit Judges Jolly, Elrod, and Willett Appeal From the United States District Court for the Middle District of Louisiana USDC No. 3:16-CV-742 Honorable Judge Brian A. Jackson, Presiding OFFICER JOHN DOE ORIGINAL BRIEF ON APPLICATION FOR REVIEW BY CERTIFIED QUESTION Respectfully submitted: ATTORNEY FOR THE APPLICANT OFFICER JOHN DOE Donna U. Grodner (20840) GRODNER LAW FIRM 2223 Quail Run, B-1 Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70808 (225) 769-1919 FAX 769-1997 [email protected] CIVIL PROCEEDING TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.. ii CERTIFIED QUESTIONS. 1 1. Whether Louisiana law recognizes a duty, under the facts alleged I the complaint, or otherwise, not to negligently precipitate the crime of a third party? 2. Assuming McKesson could otherwise be held liable for a breach of duty owed to Officer Doe, whether Louisiana’s Professional Rescuer’s Doctrine bars recovery under the facts alleged in the complaint? . 1 STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION. 1 STATEMENT OF THE CASE. 1 A. NATURE OF THE CASE. 1 B. PROCEDURAL HISTORY. 12 1. ACTION OF THE TRIAL COURT. 12 2. ACTION OF THE FIFTH CIRCUIT. 12 3. ACTION OF THE SUPREME COURT. 13 4. ACTION OF THE FIFTH CIRCUIT. 13 C. -

Black Lives Matter, American Jews, and Antisemitism: Distinguishing Between the Organization(S), the Movement, and the Ubiquitous Phrase

Black Lives Matter, American Jews, and Antisemitism: Distinguishing Between the Organization(s), the Movement, and the Ubiquitous Phrase Today’s Black Lives Matter movement has become one of the most prolific social movements in decades. It is a movement focused on improving the safety and well-being of Black people in the U.S., achieving racial justice, and ending racial disparities in all areas of our society. When Jews are asked to march with or just assert “Black lives matter,” we are not being asked to “check” our love of Israel at the door or embrace an antisemitic agenda. To most invoking the phrase, Black Lives Matter is an inspiring rallying cry, a slogan, and a demand for racial justice. That fight for racial justice is also a fight for our own multiracial, multiethnic Jewish community. The phrase “Black Lives Matter” was coined as the Twitter “hashtag” #BlackLivesMatter in response to George Zimmerman’s 2013 acquittal in 17-year-old Treyvon Martin’s murder. Both his death and Zimmerman’s acquittal sparked large-scale protests across the country. The originators of the hashtag, Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi went on to found the Black Lives Matter Network as an organizing platform for activists that emphasizes local over national leadership. The Black Lives Matter network now has 16 chapters. There are at least two other national groups with Black Lives Matter Network in their titles. Not surprisingly, the overall BLM movement is a decentralized network of activists with no formal hierarchy. In response to the high-profile police killings of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, and Tamir Rice in 2015, about 1500 activists, including those with the Black Lives Matter Network, gathered at Cleveland State University to discuss the movement. -

And Visual and Performance Art in the Era of Extrajudicial Police Killings

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 5, No. 10; October 2015 Protesting Police Violence: “Blacklivesmatter” And Visual and Performance Art in the Era of Extrajudicial Police Killings John Paul, PhD Washburn University Departments of Sociology and Art Topeka, Kansas 66621 Introduction This visual essay is an exploration of the art, performance, and visual iconography associated with the BlackLivesMatter social movement organization.[1]Here I examine art that is used to protest and draw awareness to extrajudicial violence and the “increasingly militarized systems of killer cops…in the United States of America.”[2]In this review, secondary themes of racism, dehumanization, racial profiling and political and economic injustice will also be highlighted. Ultimately this work intertwines (and illustrates with art) stories of recent and historic episodes of state violence against unarmed black and brown citizens, and my goals with this project are several. First, I simply seek to organize, in one place, a record of visual protest against excessive policing. In particular, I am interested in what these images have to say about the use of state violence when compared and analyzed collectively. Second, via these images, I hope to explore the various ways they have been used to generate commentary and suggest explanations (as well as alternatives) to racism, police brutality, and a militarized culture within police departments. Within this second goal, I ask whose consciousness is being challenged, what social change is being sought, and how these images hope to accomplish this change. Third, I claim these images as part of the symbolic soul of the BlackLivesMatter social movement—and I explore the art directly within the movement as well as the art in the surrounding culture.[3] I begin however with conceptions of social movement activism. -

Biracial Activism in the Black Lives Matter Era Maria Hamming Grand Valley State University

McNair Scholars Journal Volume 21 | Issue 1 Article 4 2017 Counting Color: Biracial Activism in the Black Lives Matter Era Maria Hamming Grand Valley State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/mcnair Recommended Citation Hamming, Maria (2017) "Counting Color: Biracial Activism in the Black Lives Matter Era," McNair Scholars Journal: Vol. 21 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/mcnair/vol21/iss1/4 Copyright © 2017 by the authors. McNair Scholars Journal is reproduced electronically by ScholarWorks@GVSU. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/ mcnair?utm_source=scholarworks.gvsu.edu%2Fmcnair%2Fvol21%2Fiss1%2F4&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages Counting Color: Biracial Activism in the Black Lives Matter Era Introduction and was pregnant. Nixon knew that Colvin would be a “political liability in certain On March 2, 1955 Claudette Colvin parts of the black community”6 and would would find a seat on a city bus in certainly fuel stereotypes from the White Montgomery, Alabama and send the community.7 Montgomery bus boycott into motion. A 10th grader at Booker T. Washington Colorism explains why Claudette High School, Claudette felt empowered Colvin was not used as the face of the by her class history lessons on Harriet Montgomery bus boycott. Color classism, Tubman and Sojourner Truth, and was or colorism, is defined as “a social, disillusioned by the “bleak racial conditions economic, and political societal framework in Montgomery.”1 Per the segregation laws that follows skin-color differences, such at the time, Claudette sat in the rear of the as those along a continuum of possible bus, which was designated for “colored” shades, those with the lightest skin color passengers. -

Blacklivesmatter 1–2/2016 Unpredictable Intimacies and Political Affects 46

SQS "Queering" #BlackLivesMatter 1–2/2016 Unpredictable Intimacies and Political Affects 46 Bessie P. Dernikos Queer/ View/Mirror Opinion Piece ABSTRACT If I die in police custody, know that I want to live! We want to live! #BlackLivesMatter (#BLM) has garnered considerable attention in We fght to live! Black Lives Mater! All Black Lives Mater! recent years with its commitment to honor all black lives, yet the (Black Lives Mater Netroots Mob 2015) affective dimensions of this global cause remain largely under- theorized. Within this piece, I explore how #BLM, as a larger sociopolitical movement, works to collectively bind strangers Te 2012 shooting of 17-year old Trayvon Martin in Sanford, Florida has together by transmitting affects that produce a sense of immediacy, intimacy, and belonging. I argue that these affective intensities garnered national atention in the United States, fueling intense speculation incite an ‘unpredictable intimacy’ that closely connects strangers to over what it means to live in a morally ambiguous world where police black bodies and intensifies the forces of race, gender, and hetero/ brutality and unchecked violence against African Americans tragically sexuality in ways that—counter to the movement’s purpose— proliferate. According to Washington Post columnist Jonathan Capehart violate the bodies of queer/black women, in particular, via the (2015): processes of replication and erasure. I conclude by proposing that, while #BLM aims to empower black lives and build a collective, we Since that rainy night three years ago, we have watched one horrifc remember the political possibilities that affect and queer theories encounter afer another involving unarmed African Americans on have to offer in order to attend to, and potentially disrupt, the the losing end of a gun or a confrontation with police. -

The Early History of the Black Lives Matter Movement, and the Implications Thereof

18 NEV. L.J. 1091, CHASE - FINAL 5/30/18 2:29 PM THE EARLY HISTORY OF THE BLACK LIVES MATTER MOVEMENT, AND THE IMPLICATIONS THEREOF Garrett Chase* INTRODUCTION From quarterbacks to hashtags, from mall demonstrations to community vigils, and from the streets of New York to the courts of Texas, the Black Lives Matter movement undisputedly has made its mark on America’s consciousness. But what is this “movement”? Where did it come from? Does Black Lives Mat- ter stand for civil rights, or human rights? What are the movement’s goals? What are its motivations? With the onslaught of media attention given to Black Lives Matter, I found the magnitude of these questions troubling. Black Lives Matter has garnered widespread awareness; yet, many know almost nothing about its origins. Black Lives Matter’s ultimate place in the historical narrative of our time is uncertain. Part viral social phenomenon, part civil rights move- ment, Black Lives Matter draws on common themes from previous civil rights movements, but is a marked departure from previous chapters of the centuries- long struggle for Black freedom and equality in America. As a matter of clarification, and with all due respect to those who were re- sponsible for the inception of the Black Lives Matter (“BLM”) movement, this Note addresses Black Lives Matter in the context of America’s history of civil rights movements. In an article for Time Magazine, one of the originators of the movement, Opal Tometi, specified that the aspirations of the movement go be- yond civil rights and that the movement characterizes itself as a human rights movement for “the full recognition of [Blacks’] rights as citizens; and it is a battle for full civil, social, political, legal, economic and cultural rights as en- * Associate Attorney at Shumway Van and William S. -

The Trump Resistance's

THE TRUMP RESISTANCE’S REPERTOIRE OF CONTENTION The Trump Resistance’s Rep- ertoire of Contention and its Practice of Civil Disobedience (2016-2018) Charlotte Thomas-Hébert Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne European Center for Sociology and Political Science (CESSP) France Abstract: The Resistance, formed in opposition to Donald Trump, has seen progressive groups ally in marches and ral- lies all over the United States. Yet one of its most striking fea- tures is that there have been few acts of civil disobedience. Using the tools of social movement studies and political soci- ology as well as ethnographic data, this paper investigates why breaking the law has not been a more popular form of nonvio- lent direct action, and why activists seemed to favor permitted marches at a time when civil disobedience had become if not le- gitimate, at least increasingly accepted as a democratic practice. 1 SOCIETY OF AMERICANISTS REVIEW he election of Barack Obama as well as the Great Reces- sion of 2008 marked a subsequent revival of protest poli- Ttics in the United States, with movements ranging from campaigns for better living wages such as Fight for $15, Black Lives Matter actions against police brutality and institutional racism and strikes in the public sector (Wisconsin in 2011, the Chicago teach- ers’ strike of 2012). Additional protest politics movements include the “Nonviolent Moral Fusion Direct Actions” of the Moral Mon- days in the South in 2013 and Occupy in 2011, that held public space in opposition to “corporate greed” and the financialization of the economy. If these movements have adopted different strategies and repertoires of contention, they have stayed clear of electoral politics and have criticized the legitimacy of the American political system. -

Racial Equity & Social Justice Resources for the Sustainability In

Racial Equity & Social Justice Resources for the Sustainability in Higher Education Community This collection of racial equity and social justice resources was initiated by the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Committee of the AASHE Advisory Council to highlight the vital work of the many incredible people and organizations who have been doing powerful work to bring attention to issues of racial and social justice. The resources are in no particular order and include links to programs and resources related to solidarity and messaging, understanding racial/social/environmental justice, race and sustainability, anti-racism, prominent influencers, podcasts, videos and articles. We encourage everyone to add to and revisit this open-source document to continue learning about racial equity and social justice issues. Solidarity Resources/Messaging ● Solidarity Messaging ● Showing Up for Racial Justice ● Medium ● University of Minnesota Institute on the Environment ● A Guide to Culturally Conscious Identifiers and Emojis Toolkits ● The Campus Divestment From Police College and University Toolkit ● American University’s Environmental Justice Toolkit Racial/Social/Environmental Justice-Understanding the Issues ● Movement for Black Lives ● Showing up for Racial Justice ● Black Lives Matter ● NAACP Environmental Justice ● Indigenous Environmental Network ● https://www.mpd150.com/ ● Campaign Zero ● Color of Change ● Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law ● Diverse: Issues in Higher Education ● Reform Alliance ● Human Rights Watch ● The Climate -

Rankine, the Condition of Black Life Is One of Mourning

‘The Condition of Black Life Is One of Mourning’ The murder of three men and six women at a church in Charleston is a national tragedy, but in America, the killing of black people is an unending spectacle. By CLAUDIA RANKINE JUNE 22, 2015 A friend recently told me that when she gave birth to her son, before naming him, before even nursing him, her first thought was, I have to get him out of this country. We both laughed. Perhaps our black humor had to do with understanding that getting out was neither an option nor the real desire. This is it, our life. Here we work, hold citizenship, pensions, health insurance, family, friends and on and on. She couldn’t, she didn’t leave. Years after his birth, whenever her son steps out of their home, her status as the mother of a living human being remains as precarious as ever. Added to the natural fears of every parent facing the randomness of life is this other knowledge of the ways in which institutional racism works in our country. Ours was the laughter of vulnerability, fear, recognition and an absurd stuckness. I asked another friend what it’s like being the mother of a black son. “The condition of black life is one of mourning,” she said bluntly. For her, mourning lived in real time inside her and her son’s reality: At any moment she might lose her reason for living. Though the white liberal imagination likes to feel temporarily bad about black suffering, there really is no mode of empathy that can replicate the daily strain of knowing that as a black person you can be killed for simply being black: no hands in your pockets, no playing music, no sudden movements, no driving your car, no walking at night, no walking in the day, no turning onto this street, no entering this building, no standing your ground, no standing here, no standing there, no talking back, no playing with toy guns, no living while black. -

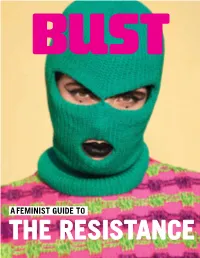

A Feminist Guide to the Resistance Table of Contents

Table of Contents 1 REVOLUTION GIRL STYLE NOW! A woman’s guide to protest, activism, and civil disobedience from fierce babes who have been there before. 9 RECLAIMING HER TIME Congresswoman Maxine Waters of California shares how to reach the votes to impeach. By Jamia Wilson 12 Don’t Get MAD, GET ELECTED! A primer for women who are curious about candidacy. By Jill Miller Zimon 18 AMERICAN WOMAN Women’s March co-chair Linda Sarsour is helping keep the #resistance alive. By Sarah Sophie Flicker 20 DESPERATELY SEEKING SOCIAL JUSTICE Meet three brave women who use detective work to expose dark money, border injustice, and hate groups. By Ian Allen 26 THE ROAD AHEAD Groundbreaking author, academic, and activ- ist bell hooks weighs in on womanhood in the era of Donald Trump. By Lux Alptraum 30 POLITICALLY CORRECT During these troubled times, we could all use a crash course in Civics 101. By Elizabeth King 34 FROM RUSSIA WITH LOVE Nadya Tolokno, of the Russian feminist punk band Pussy Riot, shares her wisdom on turn- ing art into protest. By Erika W. Smith A FEMINIST GUIDE TO THE RESISTANCE Table of Contents 1 REVOLUTION GIRL STYLE NOW! A woman’s guide to protest, activism, and civil disobedience from fierce babes who have been there before. 9 RECLAIMING HER TIME Congresswoman Maxine Waters of California shares how to reach the votes to impeach. By Jamia Wilson 12 Don’t Get MAD, GET ELECTED! A primer for women who are curious about candidacy. By Jill Miller Zimon 18 AMERICAN WOMAN Women’s March co-chair Linda Sarsour is helping keep the #resistance alive.