Arxiv:1303.1588V2 [Physics.Hist-Ph] 8 Jun 2015 4.4 Errors in the Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ball Lightning Conundrum

most famous deadis due to ball lightning occun-ed in 1752 or 1753, when die Swedish sci entist Professor Georg Wilhelm Richman was The Ball attempting to repeat Benjamin Franklin's observa dons with a lightning rcxl. An eyewitness report ed that when Richman w;is "a foot away from the iron rod, the] looked at die elecuical indicator Lightning again; just then a palish blue ball of fire, ;LS big as a fist, came out of die rod without any contaa whatst:)ever. It went right to the forehead of die Conundrum professor , who in diat instant fell back without uttering a sound."' Somedmes a luminous globe is said to rapidly descend 6own die path of a linear lightning WILLIAM D STANSFIELD strike and stop near the ground at die impact site. It may dien hover motionless in mid-air or THE EXISTENCE OF BALL UGHTNING HAS move randomly, but most often horizontally, at been questioned for hundreds of years. Today, die relatively slow velocities of walking speed. the phenomenon is a realit>' accepted by most Sometimes it touches or bounces along or near scientists, but how it is foniied and maintiiined the ground, or travels inside buildings, along has yet to be tully explained. Uncritical observers walls, or over floors before being extingui.shed. of a wide variety of glowing atmospheric entities Some balls have been observed to travel along may be prone to call tliem bail lightning. Open- power lines or fences. Wind does not .seem to minded skepdas might wish to delay judgment have any influence on how diese balls move. -

Units and Magnitudes (Lecture Notes)

physics 8.701 topic 2 Frank Wilczek Units and Magnitudes (lecture notes) This lecture has two parts. The first part is mainly a practical guide to the measurement units that dominate the particle physics literature, and culture. The second part is a quasi-philosophical discussion of deep issues around unit systems, including a comparison of atomic, particle ("strong") and Planck units. For a more extended, profound treatment of the second part issues, see arxiv.org/pdf/0708.4361v1.pdf . Because special relativity and quantum mechanics permeate modern particle physics, it is useful to employ units so that c = ħ = 1. In other words, we report velocities as multiples the speed of light c, and actions (or equivalently angular momenta) as multiples of the rationalized Planck's constant ħ, which is the original Planck constant h divided by 2π. 27 August 2013 physics 8.701 topic 2 Frank Wilczek In classical physics one usually keeps separate units for mass, length and time. I invite you to think about why! (I'll give you my take on it later.) To bring out the "dimensional" features of particle physics units without excess baggage, it is helpful to keep track of powers of mass M, length L, and time T without regard to magnitudes, in the form When these are both set equal to 1, the M, L, T system collapses to just one independent dimension. So we can - and usually do - consider everything as having the units of some power of mass. Thus for energy we have while for momentum 27 August 2013 physics 8.701 topic 2 Frank Wilczek and for length so that energy and momentum have the units of mass, while length has the units of inverse mass. -

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI)

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) m kg s cd SI mol K A NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Ambler Thompson and Barry N. Taylor NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Ambler Thompson Technology Services and Barry N. Taylor Physics Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, 1995 Edition, April 1995) March 2008 U.S. Department of Commerce Carlos M. Gutierrez, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology James M. Turner, Acting Director National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication 811, 2008 Edition (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, April 1995 Edition) Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Publ. 811, 2008 Ed., 85 pages (March 2008; 2nd printing November 2008) CODEN: NSPUE3 Note on 2nd printing: This 2nd printing dated November 2008 of NIST SP811 corrects a number of minor typographical errors present in the 1st printing dated March 2008. Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Preface The International System of Units, universally abbreviated SI (from the French Le Système International d’Unités), is the modern metric system of measurement. Long the dominant measurement system used in science, the SI is becoming the dominant measurement system used in international commerce. The Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of August 1988 [Public Law (PL) 100-418] changed the name of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and gave to NIST the added task of helping U.S. -

THE ELECTRIC DISCHARGE EXPERIMENTS a Theorist’S Exploration of First Laboratory Plasmas I

THE ELECTRIC DISCHARGE EXPERIMENTS A Theorist’s Exploration of First Laboratory Plasmas I. INTRODUCTION • Who? • Experimentalists interested in electrical properties of matter • What? • Experiments with electromagnetic fields in low-pressure Gases • Where? • Germany and Britain • When? • Late nineteenth / Early twentieth centuries • Why? • Unify classical theories for light and matter • kinetic theory, electromagnetic theory • “The study of the electrical properties of gases seems to offer the most promising field for investigatinG the Nature of Electricity and Matter, for thanks to the Kinetic Theory of Gases our idea of non-electric processes in gases is much more vivid than they are for liquids or solids”– JJ Thomson [Thomson, 1896] II. RESULTS • Failure to unify classical theories for light and matter • Evidence of complex electromagnetic interactions between light and matter at the sub-atomic level • Experimental basis for Modern Era of Physics • "a New Era has beGun in Physics, in which the electrical properties of gases have played and will play a most important part.“ JJ Thomson [Thomson, 1896] III. DISCHARGE TUBE • DischarGe Tube • Weakly-Conducting Exterior Solid • Weakly-Conducting Interior Gas (WCG) • Strongly-Conducting Interior Gas (SCG) • Applied Interior Pressure (P) • Electrodes (Cathode and Anode) • Model as Ideal Capacitor with Dielectric (D) • Applied Potential Difference (V) • Applied Electric Field (E) • Particle Drifts • Electric field transfers energy to charged particles • Particles scatter in the Gas interior -

Current-Voltage Characteristics of DC Plasma Discharges Employed In

IRAQI JOURNAL OF APPLIED PHYSICS Current-Voltage Mohammed K. Khalaf 1 Characteristics of DC Plasma Oday A. Hammadi 2 Firas J. Kadhim 3 Discharges Employed in Sputtering Techniques In this work, the current-voltage characteristics of dc plasma discharges were 1 Ministry of Science studied. The current-voltage characteristics of argon gas discharge at different and Technology, inter-electrode distances and working pressure of 0.7mbar without magnetrons Baghdad, IRAQ 2 were introduced. Then the variation of discharge current with inter-electrode Department of Physics, distance at certain discharge voltages without using magnetron was determined. College of Education, The current-voltage characteristics of discharge plasma at inter-electrode Al-Iraqia University, Baghdad, IRAQ distance of 4cm without magnetron, with only one magnetron and with dual 3 Department of Physics, magnetrons were also determined. The variation of discharge current with inter- College of Science, electrode distance at certain discharge voltage (400V) for the cases without University of Baghdad, magnetron, using one magnetron and dual magnetrons were studied. Finally, the Baghdad, IRAQ discharge current-voltage characteristics for different argon/nitrogen mixtures at total gas pressure of 0.7mbar and inter-electrode distance of 4cm were presented. Keywords: Plasma discharge; Magnetron; Glow discharge; Sputtering 1. Introduction emission effects, which lead to increase the flowing Glow discharge is low-temperature neutral current gradually approaching the breakdown point plasma where the number of electrons is equal to the beyond which the avalanche occurs and the current number of ions despite that local but negligible increases drastically in the Townsend discharge imbalances may exist at walls [1]. -

Plasma Discharge in Water and Its Application for Industrial Cooling Water Treatment

Plasma Discharge in Water and Its Application for Industrial Cooling Water Treatment A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Drexel University by Yong Yang In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2011 ii © Copyright 2008 Yong Yang. All Rights Reserved. iii Acknowledgements I would like to express my greatest gratitude to both my advisers Prof. Young I. Cho and Prof. Alexander Fridman. Their help, support and guidance were appreciated throughout my graduate studies. Their experience and expertise made my five year at Drexel successful and enjoyable. I would like to convey my deep appreciation to the most dedicated Dr. Alexander Gutsol and Dr. Andrey Starikovskiy, with whom I had pleasure to work with on all these projects. I feel thankful for allowing me to walk into their office any time, even during their busiest hours, and I’m always amazed at the width and depth of their knowledge in plasma physics. Also I would like to thank Profs. Ying Sun, Gary Friedman, and Alexander Rabinovich for their valuable advice on this thesis as committee members. I am thankful for the financial support that I received during my graduate study, especially from the DOE grants DE-FC26-06NT42724 and DE-NT0005308, the Drexel Dean’s Fellowship, George Hill Fellowship, and the support from the Department of Mechanical Engineering and Mechanics. I would like to thank the friendship and help from the friends and colleagues at Drexel Plasma Institute over the years. Special thanks to Hyoungsup Kim and Jin Mu Jung. Without their help I would not be able to finish the fouling experiments alone. -

From Cell to Battery System in Bevs: Analysis of System Packing Efficiency and Cell Types

Article From Cell to Battery System in BEVs: Analysis of System Packing Efficiency and Cell Types Hendrik Löbberding 1,* , Saskia Wessel 2, Christian Offermanns 1 , Mario Kehrer 1 , Johannes Rother 3, Heiner Heimes 1 and Achim Kampker 1 1 Chair for Production Engineering of E-Mobility Components, RWTH Aachen University, 52064 Aachen, Germany; c.off[email protected] (C.O.); [email protected] (M.K.); [email protected] (H.H.); [email protected] (A.K.) 2 Fraunhofer IPT, 48149 Münster, Germany; [email protected] 3 Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, RWTH Aachen University, 52072 Aachen, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 7 November 2020; Accepted: 4 December 2020; Published: 10 December 2020 Abstract: The motivation of this paper is to identify possible directions for future developments in the battery system structure for BEVs to help choosing the right cell for a system. A standard battery system that powers electrified vehicles is composed of many individual battery cells, modules and forms a system. Each of these levels have a natural tendency to have a decreased energy density and specific energy compared to their predecessor. This however, is an important factor for the size of the battery system and ultimately, cost and range of the electric vehicle. This study investigated the trends of 25 commercially available BEVs of the years 2010 to 2019 regarding their change in energy density and specific energy of from cell to module to system. Systems are improving. However, specific energy is improving more than energy density. -

The Modelling and Characterization of Dielectric Barrier Discharge-Based Cold Plasma Jets

The Modelling and Characterization of Dielectric Barrier Discharge-Based Cold Plasma Jets The Modelling and Characterization of Dielectric Barrier Discharge-Based Cold Plasma Jets By G. Divya Deepak, Narendra Kumar Joshi and Ram Prakash The Modelling and Characterization of Dielectric Barrier Discharge-Based Cold Plasma Jets By G. Divya Deepak, Narendra Kumar Joshi and Ram Prakash This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by G. Divya Deepak, Narendra Kumar Joshi and Ram Prakash All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-4539-3 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-4539-7 CONTENTS List of Figures........................................................................................... viii List of Tables ............................................................................................. xii List of Abbreviations ................................................................................ xiii Acknowledgements ................................................................................... xv Preface ..................................................................................................... -

AP Physics 2: Algebra Based

AP® PHYSICS 2 TABLE OF INFORMATION CONSTANTS AND CONVERSION FACTORS -27 -19 Proton mass, mp =1.67 ¥ 10 kg Electron charge magnitude, e =1.60 ¥ 10 C -27 -19 Neutron mass, mn =1.67 ¥ 10 kg 1 electron volt, 1 eV= 1.60 ¥ 10 J -31 8 Electron mass, me =9.11 ¥ 10 kg Speed of light, c =3.00 ¥ 10 m s Universal gravitational Avogadro’s number, N 6.02 1023 mol- 1 -11 3 2 0 = ¥ constant, G =6.67 ¥ 10 m kg s Acceleration due to gravity 2 Universal gas constant, R = 8.31 J (mol K) at Earth’s surface, g = 9.8 m s -23 Boltzmann’s constant, kB =1.38 ¥ 10 J K 1 unified atomic mass unit, 1 u=¥= 1.66 10-27 kg 931 MeV c2 -34 -15 Planck’s constant, h =¥=¥6.63 10 J s 4.14 10 eV s -25 3 hc =¥=¥1.99 10 J m 1.24 10 eV nm -12 2 2 Vacuum permittivity, e0 =8.85 ¥ 10 C N m 9 22 Coulomb’s law constant, k =1 4pe0 = 9.0 ¥ 10 N m C -7 Vacuum permeability, mp0 =4 ¥ 10 (T m) A -7 Magnetic constant, k¢ =mp0 4 = 1 ¥ 10 (T m) A 1 atmosphere pressure, 1 atm=¥= 1.0 1052 N m 1.0¥ 105 Pa meter, m mole, mol watt, W farad, F kilogram, kg hertz, Hz coulomb, C tesla, T UNIT second, s newton, N volt, V degree Celsius, ∞C SYMBOLS ampere, A pascal, Pa ohm, W electron volt, eV kelvin, K joule, J henry, H PREFIXES VALUES OF TRIGONOMETRIC FUNCTIONS FOR COMMON ANGLES Factor Prefix Symbol q 0 30 37 45 53 60 90 12 tera T 10 sinq 0 12 35 22 45 32 1 109 giga G cosq 1 32 45 22 35 12 0 106 mega M 103 kilo k tanq 0 33 34 1 43 3 • 10-2 centi c 10-3 milli m The following conventions are used in this exam. -

Plasma of Underwater Electric Discharges with Metal Vapors V.F

PLASMA OF UNDERWATER ELECTRIC DISCHARGES WITH METAL VAPORS V.F. Boretskij1, A.N. Veklich1, T.A. Tmenova1, Y. Cressault2, F. Valensi2, K.G. Lopatko3, Y.G. Aftandilyants3 1Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, Kyiv, Ukraine; 2Universite Paul Sabatier, Toulouse, France; 3National University of Life and Environmental Sciences of Ukraine, Kyiv, Ukraine E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] This paper deals with spectroscopy of underwater electric discharge plasma with. In particular, the focus is on configuration where the electrodes are immersed in liquid and its application in nanoscience and biotechnology. General overview of the experimental approach adopted by authors aiming to study the water-submerged electrical discharge plasma and effects of various parameters on its properties is described. The electron density was estimated on the base of spectral line broadening and shifting. PACS: 52.25.−b, 52.80.−s, 52.80.Wq INTRODUCTION components are typically studied in distinct fields of PLASMAS IN LIQUID research. Plasmas in liquid are becoming an increasingly PLASMA-LIQUID INTERACTIONS FOR important topic in the field of plasma science and NANOMATERIAL SYNTHESIS technology. In the last two decades, attention of research on the The focus of this paper, in particular, is directed interactions of plasmas with liquids has spread on a towards a relatively new branch of plasma research, variety of applications that include electrical switching nanomaterial synthesis through plasma–liquid [1], analytical chemistry [2], environmental remediation interactions, which has been developing rapidly, mainly [3, 4], sterilization and medical applications [5], etc. due to the various recently developed plasma sources These opportunities have challenged plasma community operating at low and atmospheric pressures. -

Modern GPU Architecture

Modern GPU Architecture Msc Software Engineering student of Tartu University Ismayil Tahmazov [email protected] Agenda • What is a GPU? • GPU evolution!! • GPU costs • GPU pipeline • Fermi architecture • Kepler architecture • Pascal architecture • Turing architecture • AMD Radeon R9 • AMD vs Nvidia What is it a GPU? A graphics processing unit is a specialized electronic circuit designed to rapidly manipulate and alter memory to accelerate the creation of images in a frame buffer intended for output to a display device. photo reference Wikipedia What is it a GPU? GPU Evolution image:reference Evolution of Nvidia GeForce 1999 - 2018 Modern GPU First GPU Nvidia GeForce 256 GeForce GTX 1050 CUDA CUDA is a parallel computing platform and programming model developed by NVIDIA for general computing on graphical processing units (GPUs). With CUDA, developers are able to dramatically speed up computing applications by harnessing the power of GPUs. text source photo reference Graphics Processing image:refence source Nvidia GeForce 8880 GPU pipeline Why GPUs so fast ? Why GPUs so fast ? simplified Nvidia GPU architecture MP = Multi Processor SM = Shared Memory SFU = Special Functions Unit IU = Instruction Unit SP = Streaming processor reference Nvidia Fermi GPU Architecture Nvidia Fermi GPU Architecture photo Nvidia Kepler GPU Architecture reference Specifications reference for table Pascal architecture reference GP100 (Tesla P100) image Pascal Streaming Multiprocessor Compute Capabilities: GK110 vs GM200 vs GP100 Cross-section Illustrating GP100 adjacent HBM2 stacks Cross-section Photomicrograph of a P100 HBM2 stack and GP100 GPU image reference image refence Nvidia Turing GPU Architecture reference Nvidia Turing TU102 GPU reference NVIDIA Pascal GP102 vs Turing TU102 reference Turing Streaming Multiprocessor (SM) reference New shared memory architecture reference Turing Shading Performance reference Costs !!! Really? image image Conclusion We have several GPU architectures from different companies. -

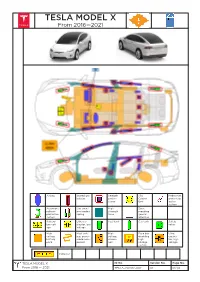

TESLA MODEL X from 2016—2021

TESLA MODEL X From 2016—2021 Airbag Stored gas Seatbelt SRS Pedestrian inflator preten- Control protection sioner Unit active system Automatic Gas strut/ High Zone rollover pre-loaded strength requiring protection spring zone special system attention Battery Ultra ca- Fuel tank Gas tank Safety low volt- pacitor, low valve age voltage High High volt- High Fuse box Ultra voltage age power voltage disabling capaci- battery cable/com- discon- high tor, high pack ponent nect voltage voltage system Cable cut TESLA MODEL X ID No. Version No. Page No. From 2016 — 2021 TESLA–202012–002 01 01/04 1. Identification / recognition WARNING LACK OF ENGINE NOISE DOES NOT MEAN VEHICLE IS OFF. SILENT MOVEMENT OR INSTANT RESTART CAPABILITY EXISTS UNTIL VEHICLE IS FULLY SHUT DOWN. WEAR APPROPRIATE PERSONAL PROTECTIVE EQUIPMENT (PPE). NOTE: The Tesla emblem indicates a fully electric vehicle. NOTE: The model name is located on the rear of the vehicle. 2. Immobilization / stabilization / lifting IMMOBILIZATION STABILIZATION/ LIFTING POINTS 1. CHOCK WHEELS 2. PUT VEHICLE INTO PARK POSITION Appropriate lift areas PUSH 1x Safe stabilization points for Model X resting on its side High Voltage (HV) Battery 3. Disable direct hazards / safety regulations ACCESS MAIN DISABLE METHOD 1. Open the hood (see chapter 4). 1. Double cut the first responder loop. 2. Remove the access panel by pulling it upward 2. Disable the 12V battery. to release the clips that hold it in place. WARNING Not every high voltage component is labeled. Always wear appropriate PPE. Always double cut the first responder loop. Do not attempt to open the High Voltage (HV) battery.