Romantic Poetry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post-War English Literature 1945-1990

Post-War English Literature 1945-1990 Sara Martín Alegre P08/04540/02135 © FUOC • P08/04540/02135 Post-War English Literature 1945-1990 Index Introduction............................................................................................... 5 Objectives..................................................................................................... 7 1. Literature 1945-1990: cultural context........................................ 9 1.1. The book market in Britain ........................................................ 9 1.2. The relationship between Literature and the universities .......... 10 1.3. Adaptations of literary works for television and the cinema ...... 11 1.4. The minorities in English Literature: women and post-colonial writers .................................................................... 12 2. The English Novel 1945-1990.......................................................... 14 2.1. Traditionalism: between the past and the present ..................... 15 2.2. Fantasy, realism and experimentalism ........................................ 16 2.3. The post-modern novel .............................................................. 18 3. Drama in England 1945-1990......................................................... 21 3.1. West End theatre and the new English drama ........................... 21 3.2. Absurdist drama and social and political drama ........................ 22 3.3. New theatre companies and the Arts Council ............................ 23 3.4. Theatre from the mid-1960s onwards ....................................... -

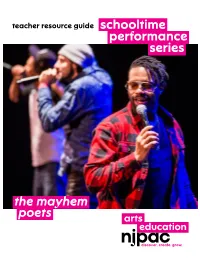

The Mayhem Poets Resource Guide

teacher resource guide schooltime performance series the mayhem poets about the who are in the performance the mayhem poets spotlight Poetry may seem like a rarefied art form to those who Scott Raven An Interview with Mayhem Poets How does your professional training and experience associate it with old books and long dead poets, but this is inform your performances? Raven is a poet, writer, performer, teacher and co-founder Tell us more about your company’s history. far from the truth. Today, there are many artists who are Experience has definitely been our most valuable training. of Mayhem Poets. He has a dual degree in acting and What prompted you to bring Mayhem Poets to the stage? creating poems that are propulsive, energetic, and reflective Having toured and performed as The Mayhem Poets since journalism from Rutgers University and is a member of the Mayhem Poets the touring group spun out of a poetry of current events and issues that are driving discourse. The Screen Actors Guild. He has acted in commercials, plays 2004, we’ve pretty much seen it all at this point. Just as with open mic at Rutgers University in the early-2000s called Mayhem Poets are injecting juice, vibe and jaw-dropping and films, and performed for Fiat, Purina, CNN and anything, with experience and success comes confidence, Verbal Mayhem, started by Scott Raven and Kyle Rapps. rhymes into poetry through their creatively staged The Today Show. He has been published in The New York and with confidence comes comfort and the ability to be They teamed up with two other Verbal Mayhem regulars performances. -

Saving Sarah Fricker: Accurately Representing the Realities of the Coleridges’ Marriage

Saving Sarah Fricker: Accurately Representing the Realities of the Coleridges’ Marriage Saving Sarah Fricker: Accurately Representing the Realities of the Coleridges’ Marriage Cori Mathis Abstract The Lake Poets circle was prolific; they wrote letters to each other constantly, leaving a clear picture of the beginning and eventual decline of the marriage between Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Sarah Fricker Coleridge. Coleridge also was fond of chronicling his personal life in his work. Coleridge’s poetry and prose clearly show that, though he may have come to regret it, he originally married Sarah Fricker for love and was very happy in the beginning of their relationship. The problem with their marriage was that they were just fundamentally incompatible, something that was not Sarah Fricker’s fault—she was a product of her society and simply unprepared to be a wife to someone like Coleridge. Unfortunately, scholars have taken Coleridge’s letters as pure truth and seem to have forgotten that every marriage has two partners, both with their own perspectives. This reflects a deliberate ignorance of Coleridge’s tendency to see situations quite differently from how they actually were. Because of this tradition, Sarah Fricker Coleridge is often portrayed as difficult at best and a harridan at worst. It does not help that she attempted to help her husband’s reputation by the majority of their letters that she possessed—one cannot see her side as clearly. In this essay, I hope to prove that she was simply an unhappy wife, married to a poetic genius who had decided she was the impediment to his happiness while she only wanted to keep their family together and safe. -

Introduction: Professionalism and the Lake School of Poetry

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-15279-2 - The Lake Poets and Professional Identity Brian Goldberg Excerpt More information Introduction: Professionalism and the Lake School of Poetry When William Wordsworth, Robert Southey, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge – the Lake school – formulated their earliest descrip- tions of the role of the poet, two models of vocational identity exerted special pressure on their thinking. One was the idea of the professional gentleman. In their association of literary composi- tion with socially useful action, their conviction that the judgment of the poet should control the literary marketplace, and their efforts to correlate personal status with the poet’s special training, the Lake writers modified a progressive version of intellectual labor that was linked, if sometimes problematically, to develop- ments in the established professions of medicine, church, and law. In short, they attempted to write poetry as though writing poetry could duplicate the functions of the professions. The other model, and it is related to the first, is literary. Like the Lake poets, earlier eighteenth-century authors had been stimulated, if occasionally frustrated, by the puzzle of how to write poetry in the face of changing conceptions of intellectual work. While ideals of medi- cal, legal, and theological effectiveness that measured ‘‘techni- que’’ were competing with those that emphasized ‘‘character,’’ literary production was moving (more slowly and less completely than is sometimes thought) from a patronage- to a market-based 1 model. Eighteenth-century writers developed a body of figural resources such as the poetic wanderer that responded to new constructions of experience, merit, and evaluation, and the Lake writers seized on these resources in order to describe their own professional situation. -

ABSURDNÍ DRAMA (Překlad „Theatre of the Absurd“; Z Lat

STRUČNÝ ABECENDNÍ PŘEHLED LITERÁRNÍCH SMĚRŮ, HNUTÍ A SKUPIN Uvedený přehled by měl studentům románských literatur (ale nejen jim) usnadnit orientaci ve vybraných literárněvědných pojmech. Nečiní si nároky na úplnost a jeho autor bude vděčný za jakékoli doplňky a upřesnění, ale také za opravy nepřesností, kterých se nevěda či mimoděk dopustil. Předem za ně děkuje Petr Kyloušek ([email protected]). ABSURDNÍ DRAMA (překlad „theatre of the absurd“; z lat. „absurdus“ = „sluchu nelibý“, „nemístný“, „nesmyslný“) je označení, kterým Martin Esslin charakterizoval typ dramatické tvorby, jež se rozvinula v 50. a 60. letech 20. stol. Ve franc. kontextu se vedle toho užívaly termíny „antidivadlo“ a „nové divadlo“ („antithéâtre“; „nouveau théâtre“), navozující paralelu s novým románem. V obou případech se totiž jedná o analogický projev týchž modernistických tendencí pramenících z týchž ontologických a noetických předpokladů – ze zpochybnění esencialistického modelu uchopení skutečnosti a tím i tradiční mimeze. Termín nadto odráží dobový vliv literárního existencialismu zesílený poválečnou citlivostí k mezním situacím, existenciálním otázkám, metafyzické úzkosti. V širším smyslu se hovoří o absurdní literatuře, tedy o přítomnosti absurdity v próze (groteska, černý humor) a poezii (nonsens). Poetika absurdního dramatu rozrušuje tradiční pojetí výstavby – charakterologii postav, motivaci jednání, ztvárnění časoprostoru, realistické ukotvení, strukturu dialogu, ba zpochybňuje komunikativní funkci řeči vůbec. Chybí nejen tradiční členění dramatické -

The Fragmentation of Imagism It Was 1912, and a New Mode of Poetry Was Taking Root

The Fragmentation of Imagism It was 1912, and a new mode of poetry was taking root. Sparked by the ideas of T.E. Hulme and from distaste of the drippy sentimentalism of the Romantic era (Britannica “Imagist”), Ezra Pound, Richard Aldington, and H.D. literally wrote the rules of Imagism. Their dry, concise look at an image or “complex,” as Pound described it, helped lay the foundation for modernist poetry. However, the Imagists’ granite rules could not ensure strict adherence to their form, not even from founding members of Imagism themselves. As the years went by, the Imagists themselves grew weary of their own form by both their own admittance and through their later works. Ezra Pound was the first leader of the Imagist movement, and his autocratic grip on the concept of Imagism may be partly to blame for the fragmentation of the movement. Pound makes it quite clear that, “At least for myself, I want [twentieth-century poetry] so, austere, direction, free from emotional slither (“A Retrospect” 23).” He carefully selected and edited poems for published volumes of Imagist poetry, but the appearance of the popular and wealthy poet heiress Amy Lowell swept in a new democratic format for the group’s publications. Authors were to select what they considered their best work, without the stamp of approval from Pound deeming it true to the Imagist credo (Bradshaw 159). Amy Lowell and Ezra Pound clashed quite famously over the direction Imagism would take, as seen in Lowell’s poem to Pound, harshly dubbed “Astigmatism.” The poem pulls no punches; the analogy is clear in Lowell’s image of the Poet smashing lovely flowers of all kinds, saying “They are useless. -

THE UNIVERSITY of HULL Four Literary Protegees of the Lake

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL Four Literary Protegees of the Lake Poets: Caroline Bowles, Maria Gowen Brooks, Sara Coleridge and Maria Jane Jewsbury being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Hull by Dennis Jun-Yu Low, SA (Oxon) March 2003 Therefore, although it be a history Homely and rude, I will relate the same For the delight of a few natural hearts: And, with yet fonder feeling, for the sake Of youthful Poets, who among these hills Will be my second self when I am gone. Wordsworth Contents Contents ......................................................................................................................................... 1 Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................ 2 List of Abbreviations ....................................................................................................................... 4 Preface ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Chapter 1: The Lake Poets and 'The Era of Accomplished Women' ............................................ 13 Chapter 2: Caroline Bowles .......................................................................................................... 51 Chapter 3: Maria Gowen Brooks ................................................................................................ 100 Chapter 4: Sara Coleridge ......................................................................................................... -

SURREALISM IS a THING RUBRICS and OBJECTIVATION in the SURREALIST PERIODICAL, 1924–2015 Catherine Hansen

ARTICLE Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/artm/article-pdf/5/3/62/1832938/artm_a_00158.pdf by guest on 28 September 2021 SURREALISM IS A THING RUBRICS AND OBJECTIVATION IN THE SURREALIST PERIODICAL, 1924–2015 Catherine hansen What Will Be is the title of a 2014 anthology compiled by members of a 21st-century international network of Surrealist groups, announcing the continuing ambitions of a movement that fi rst began amid the sleeping fi ts and Dada-inspired provocations of the early 1920s. The anthology includes a special feature on the publishing activities of the various groups, which frequently coordinate their efforts across group and national boundaries—operating as a kind of dispersed organism whose vital functions have never seen fi t to cease, even as Surrealism has come to be considered a historical and concluded phenomenon. There is particular emphasis on the Surrealist attitude, in general, toward publishing, publicization, circulation, the digital revolution, and the rise of on-demand printing. Contributors, for example, speak- ing on behalf of the Montreal- and Miami-based Surrealist publisher Editions Sonámbula, state: “any attempt aiming to expand the fi eld of the real and of the poetic has necessarily to refl ect on the means of communication to use.”1 Surrealism has always claimed to extend the domain of what is 1 “The Utility of Surrealist Editions and of the Surrealist Gallery: An Inquiry,” in Ce qui sera/What Will Be/Lo que serà: Almanac of the International Surrealist Movement, “hors- série” number of Brumes Blondes, ed. Her de Vries and Laurens Vancrevel (Amsterdam: Brumes Blondes, 2014), 438–39. -

Thomas De Quinceys Portrait of the Lake Poets

69 Thomas De Quincey’s Portrait of the Lake Poets: Individual Reality and Universal Ideal Akira Fujimaki Introduction: Pictorial versus Literary Portraits As David Piper (120) and Richard Holmes (12) concurrently mention, Washing- ton Allston, the American painter of arguably the best portrait of Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834) [Figure 1], confessed to feeling incompetent to paint the poet in 1814: So far as I can judge of my own production the likeness of Coleridge is a true one, but it is Coleridge in repose; and, though not unstirred by the perpetual ground-swell of his ever-working intellect, and shadowing forth something of the deep philosopher, it is not Coleridge in his highest mood, the poetic state, when the divine affl atus of the poet possessed him. When in that state, no face I ever saw was like his; it seemed almost spirit made visible without a shadow of the physical upon it. Could I then have fi xed it upon canvas! but it was beyond the reach of my art. (Flagg 104) Morton D. Paley, who has studied the portraits of the poet, suggests one of the 70 reasons why it is not easy to paint him: “it does seem as if Coleridge’s personal appearance could vary dramatically within short periods, and this may have been one of the effects of his opium ad- diction” (45). We have to consider other effects as well. According to Frances Blanshard, who has done thorough research on all the extant portraits of William Words- worth (1770-1850), portrait painters of these Romantic poets, under the re- maining infl uence of Sir Joshua Reyn- olds’s classicist theory of art, usually did not pursue the likeness or singu- Fig. -

The “Objectivists”: a Website Dedicated to the “Objectivist” Poets by Steel Wagstaff a Dissertation Submitted in Partial

The “Objectivists”: A Website Dedicated to the “Objectivist” Poets By Steel Wagstaff A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN‐MADISON 2018 Date of final oral examination: 5/4/2018 The dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Lynn Keller, Professor, English Tim Yu, Associate Professor, English Mark Vareschi, Assistant Professor, English David Pavelich, Director of Special Collections, UW-Madison Libraries © Copyright by Steel Wagstaff 2018 Original portions of this project licensed under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license. All Louis Zukofsky materials copyright © Musical Observations, Inc. Used by permission. i TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ..................................................................................... vi Abstract ................................................................................................... vii Introduction ............................................................................................... 1 The Lives ................................................................................................ 31 Who were the “Objectivists”? .............................................................................................................................. 31 Core “Objectivists” .............................................................................................................................................. 31 The Formation of the “Objectivist” -

I Was a Poet, I Was Young”: a Reconsideration of the Georgian Group

”I was a poet, I was young”: a reconsideration of the Georgian group Cora MacGregor Published: 23 May 2020 Keywords: Georgian, poetry, traditional, literary past, divine, modernity Broad Street Humanities Review, 2 www.broadstreethumanitiesreview.com Broad Street Humanities Review, 2 2 of 10 1. Introduction In a 1932 article written for The Bookman, Wilfred Gibson, a former member of the self- titled Georgian group, acknowledged somewhat mournfully the infelicitous fate of their chosen nomen: if a young critic wishes to say something really nasty about another writer, he accuses them of being a Georgian poet; and in so doing not only offers him the last insult, but commits him irretrievably to the limbo of forgotten things.1 The dual effect of the insult, identified by Gibson here, offers a synecdochal vision of the movement’s legacy following the publication of the final Georgian Poetry, a biennial anthology which ran between 1911 and 1922: treated with contempt by their immediate successors, the repute of the group dwindled to the point of obsolescence. Recent critical accounts of early twentieth century literature tend to handle the ‘problem’ of the Georgians by making sweeping statements about their poetic commitments, which endeavour to impose a homogeneity upon this miscellaneous coalescence of young poets, brought together under the mentorship of Edward Marsh. One such assessment is made by C. K. Stead, whose characterisation of the Georgians typifies the modern attitude, being for the most part comparative: he contrasts them against -

Wholly Communion, Literary Nationalism, and the Sorrows of the Counterculture Daniel Kane

Wholly Communion, Literary Nationalism, and the Sorrows of the Counterculture Daniel Kane all those americans here writing about america it’s time to give something back, after all our heroes were always the gangster the outlaw why surprised you act like it now, a place the simplest man was always the most complex you gave me the usual things, comics, music, royal blue drape suits & what they ever give me but unreadable books? Tom Raworth, “I Mean” These opening lines from “I Mean” by British poet Tom Raworth, published in 1967 in Raworth’s fi rst full- length collection, The Relation Ship (Goliard Press),1 stand as a kind of metaphor for a larger problem facing British avant- garde poetry in the 1960s. Put simply, “I Mean” addresses an “American” infl uence on British letters that was to weigh heavily on poets challenging the restrained formalism and hostility to the modernist project characteris- tic of the British “Movement” poets.2 How were the many Beat and Black Mountain– enamored versifi ers of Albion to be innovative on their own terms? The avant- garde, as Raworth seems to have it, is predicated on the aura of the “outlaw,” the “gangster.” Such fi gures are suggestively American, par- ticularly when read within the context of the poem’s opening lines. American signs pointing the way forward for a developing British poetics include an idealized simplicity, comics, and music.3 Raworth’s poem works in part to ask whether the English will be able to “give something back.” What would that “something” sound like? What would it look like? Would it be somehow Framework 52, No.