Mahadevi Verma Mythili P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post-War English Literature 1945-1990

Post-War English Literature 1945-1990 Sara Martín Alegre P08/04540/02135 © FUOC • P08/04540/02135 Post-War English Literature 1945-1990 Index Introduction............................................................................................... 5 Objectives..................................................................................................... 7 1. Literature 1945-1990: cultural context........................................ 9 1.1. The book market in Britain ........................................................ 9 1.2. The relationship between Literature and the universities .......... 10 1.3. Adaptations of literary works for television and the cinema ...... 11 1.4. The minorities in English Literature: women and post-colonial writers .................................................................... 12 2. The English Novel 1945-1990.......................................................... 14 2.1. Traditionalism: between the past and the present ..................... 15 2.2. Fantasy, realism and experimentalism ........................................ 16 2.3. The post-modern novel .............................................................. 18 3. Drama in England 1945-1990......................................................... 21 3.1. West End theatre and the new English drama ........................... 21 3.2. Absurdist drama and social and political drama ........................ 22 3.3. New theatre companies and the Arts Council ............................ 23 3.4. Theatre from the mid-1960s onwards ....................................... -

Title <Translated Article> Western Zhou History in the Collective

<Translated Article> Western Zhou History in the Collective Title Memory of the People of the Western Zhou: An Interpretation of the Inscription of the "Lai pan" Author(s) MATSUI, Yoshinori Citation 東洋史研究 (2008), 66(4): 712-664 Issue Date 2008-03 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/141873 Right Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University 712 WESTERN ZHOU HISTORY IN THE COLLECTIVE MEMORY OF THE PEOPLE OF THE WESTERN ZHOU: AN INTERPRETATION OF THE INSCRIPTION OF THE "LAI PAN" MATSUI Y oshinori Introduction On January 19, 2003, twenty-seven bronze pieces were excavated from a hoard at Yangjiacun (Meixian county, Baoji city, Shaanxi province).l All the bronzes, which include twelve ding ~, nine Ii rn, two fanghu 11 if., one pan ~, one he :ii\'t, one yi [ffi, and one yu k, have inscriptions. Among them, the bronzes labeled "Forty-second-year Lai ding" ~ ~ (of which there are two pieces), "Forty-third-year Lai ding" (ten pieces), and "Lai pan" ~~ (one piece) have in scriptions that are particularly long for inscriptions from the Western Zhou period and run respectively to 281, 316 and 372 characters in length. The inscription of the "Lai pan," containing 372 characters, is divided into two parts, the first part is narrated from Lai's point of view but employs the third-person voice, opening with the phrase, "Lai said." The second part records an appointment (ceming :IlJt frJ) ceremony that opens, "The King said." The very exceptional first part records the service of generations of Lai's ancestors to successive Zhou Kings. The inscription mentions eleven former kings, King Wen X3:., King Wu TIk3:., King Cheng JIlG3:., King Kang *3:., King Zhao BR3:., King Mu ~~3:., King Gong *3:., King Yi i~3:., King Xiao ~(~)3:., King Yi 1J$(~)3:., King Li Jj1U (J~)3:. -

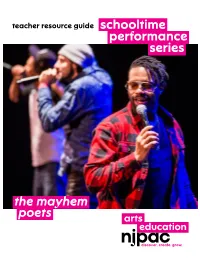

The Mayhem Poets Resource Guide

teacher resource guide schooltime performance series the mayhem poets about the who are in the performance the mayhem poets spotlight Poetry may seem like a rarefied art form to those who Scott Raven An Interview with Mayhem Poets How does your professional training and experience associate it with old books and long dead poets, but this is inform your performances? Raven is a poet, writer, performer, teacher and co-founder Tell us more about your company’s history. far from the truth. Today, there are many artists who are Experience has definitely been our most valuable training. of Mayhem Poets. He has a dual degree in acting and What prompted you to bring Mayhem Poets to the stage? creating poems that are propulsive, energetic, and reflective Having toured and performed as The Mayhem Poets since journalism from Rutgers University and is a member of the Mayhem Poets the touring group spun out of a poetry of current events and issues that are driving discourse. The Screen Actors Guild. He has acted in commercials, plays 2004, we’ve pretty much seen it all at this point. Just as with open mic at Rutgers University in the early-2000s called Mayhem Poets are injecting juice, vibe and jaw-dropping and films, and performed for Fiat, Purina, CNN and anything, with experience and success comes confidence, Verbal Mayhem, started by Scott Raven and Kyle Rapps. rhymes into poetry through their creatively staged The Today Show. He has been published in The New York and with confidence comes comfort and the ability to be They teamed up with two other Verbal Mayhem regulars performances. -

The Fragmentation of Imagism It Was 1912, and a New Mode of Poetry Was Taking Root

The Fragmentation of Imagism It was 1912, and a new mode of poetry was taking root. Sparked by the ideas of T.E. Hulme and from distaste of the drippy sentimentalism of the Romantic era (Britannica “Imagist”), Ezra Pound, Richard Aldington, and H.D. literally wrote the rules of Imagism. Their dry, concise look at an image or “complex,” as Pound described it, helped lay the foundation for modernist poetry. However, the Imagists’ granite rules could not ensure strict adherence to their form, not even from founding members of Imagism themselves. As the years went by, the Imagists themselves grew weary of their own form by both their own admittance and through their later works. Ezra Pound was the first leader of the Imagist movement, and his autocratic grip on the concept of Imagism may be partly to blame for the fragmentation of the movement. Pound makes it quite clear that, “At least for myself, I want [twentieth-century poetry] so, austere, direction, free from emotional slither (“A Retrospect” 23).” He carefully selected and edited poems for published volumes of Imagist poetry, but the appearance of the popular and wealthy poet heiress Amy Lowell swept in a new democratic format for the group’s publications. Authors were to select what they considered their best work, without the stamp of approval from Pound deeming it true to the Imagist credo (Bradshaw 159). Amy Lowell and Ezra Pound clashed quite famously over the direction Imagism would take, as seen in Lowell’s poem to Pound, harshly dubbed “Astigmatism.” The poem pulls no punches; the analogy is clear in Lowell’s image of the Poet smashing lovely flowers of all kinds, saying “They are useless. -

Foreigners and Propaganda War and Peace in the Imperial Images of Augustus and Qin Shi Huangdi

Foreigners and Propaganda War and Peace in the Imperial Images of Augustus and Qin Shi Huangdi This thesis is presented by Dan Qing Zhao (317884) to the School of Historical and Philosophical Studies in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the field of Classics in the School of Historical and Philosophical Studies Faculty of Arts University of Melbourne Principal Supervisor: Dr Hyun Jin Kim Secondary Supervisor: Associate Professor Frederik J. Vervaet Submission Date: 20/07/2018 Word Count: 37,371 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements i Translations and Transliterations ii Introduction 1 Current Scholarship 2 Methodology 7 Sources 13 Contention 19 Chapter One: Pre-Imperial Attitudes towards Foreigners, Expansion, and Peace in Early China 21 Western Zhou Dynasty and Early Spring and Autumn Period (11th – 6th century BCE) 22 Late Spring and Autumn Period (6th century – 476 BCE) 27 Warring States Period (476 – 221 BCE) 33 Conclusion 38 Chapter Two: Pre-Imperial Attitudes towards Foreigners, Expansion, and Peace in Rome 41 Early Rome (Regal Period to the First Punic War, 753 – 264 BCE) 42 Mid-Republic (First Punic War to the End of the Macedonian Wars, 264 – 148 BCE) 46 Late Republic (End of the Macedonian Wars to the Second Triumvirate, 148 – 43 BCE) 53 Conclusion 60 Chapter Three: Peace through Warfare 63 Qin Shi Huangdi 63 Augustus 69 Conclusion 80 Chapter Four: Morality, Just War, and Universal Consensus 82 Qin Shi Huangdi 82 Augustus 90 Conclusion 104 Chapter Five: Victory and Divine Support 106 Qin Shi Huangdi 108 Augustus 116 Conclusion 130 Conclusion 132 Bibliography 137 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to offer my sincerest thanks to Dr Hyun Jin Kim. -

Download File

On the Periphery of a Great “Empire”: Secondary Formation of States and Their Material Basis in the Shandong Peninsula during the Late Bronze Age, ca. 1000-500 B.C.E Minna Wu Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMIBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 @2013 Minna Wu All rights reserved ABSTRACT On the Periphery of a Great “Empire”: Secondary Formation of States and Their Material Basis in the Shandong Peninsula during the Late Bronze-Age, ca. 1000-500 B.C.E. Minna Wu The Shandong region has been of considerable interest to the study of ancient China due to its location in the eastern periphery of the central culture. For the Western Zhou state, Shandong was the “Far East” and it was a vast region of diverse landscape and complex cultural traditions during the Late Bronze-Age (1000-500 BCE). In this research, the developmental trajectories of three different types of secondary states are examined. The first type is the regional states established by the Zhou court; the second type is the indigenous Non-Zhou states with Dong Yi origins; the third type is the states that may have been formerly Shang polities and accepted Zhou rule after the Zhou conquest of Shang. On the one hand, this dissertation examines the dynamic social and cultural process in the eastern periphery in relation to the expansion and colonization of the Western Zhou state; on the other hand, it emphasizes the agency of the periphery during the formation of secondary states by examining how the polities in the periphery responded to the advances of the Western Zhou state and how local traditions impacted the composition of the local material assemblage which lay the foundation for the future prosperity of the regional culture. -

Gopal Singh Nepali - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Gopal Singh Nepali - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Gopal Singh Nepali(1911–1963) Gopal Singh Nepali was an eminent poet of Hindi literature and a famous lyricist of Bollywood. His association with Bollywood spanned around two decades, beginning in 1944 and ended with his death in 1963. He was a poet of post- Chhayavaad period, and he wrote several collections of Hindi poems including "Umang" (published in 1933). He was also a journalist and edited at least four Hindi magazines, namely, Ratlam Times, Chitrapat, Sudha, and Yogi. He was born in Bettiah in the state of Bihar. In fact, he was not a Nepali but has taken this as a part of his literary name. During Sino-Indian War of 1962, he wrote many patriotic songs and poems which include Savan, Kalpana, Neelima, Naveen Kalpana Karo,etc. www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 Apnepan Ka Matvala Gopal Singh Nepali www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 2 Badnam Rahe Batmar Gopal Singh Nepali www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 3 Basanta Git Gopal Singh Nepali www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 4 Chowpatty Ka Suryasta Gopal Singh Nepali www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 5 Dipak Jalta Rahe Ratbhar Gopal Singh Nepali www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 6 Do Pran Mile Gopal Singh Nepali www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 7 Dur Jakar Na Koi Bisara Kare Gopal Singh Nepali www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 8 Garib Ka Salam -

SURREALISM IS a THING RUBRICS and OBJECTIVATION in the SURREALIST PERIODICAL, 1924–2015 Catherine Hansen

ARTICLE Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/artm/article-pdf/5/3/62/1832938/artm_a_00158.pdf by guest on 28 September 2021 SURREALISM IS A THING RUBRICS AND OBJECTIVATION IN THE SURREALIST PERIODICAL, 1924–2015 Catherine hansen What Will Be is the title of a 2014 anthology compiled by members of a 21st-century international network of Surrealist groups, announcing the continuing ambitions of a movement that fi rst began amid the sleeping fi ts and Dada-inspired provocations of the early 1920s. The anthology includes a special feature on the publishing activities of the various groups, which frequently coordinate their efforts across group and national boundaries—operating as a kind of dispersed organism whose vital functions have never seen fi t to cease, even as Surrealism has come to be considered a historical and concluded phenomenon. There is particular emphasis on the Surrealist attitude, in general, toward publishing, publicization, circulation, the digital revolution, and the rise of on-demand printing. Contributors, for example, speak- ing on behalf of the Montreal- and Miami-based Surrealist publisher Editions Sonámbula, state: “any attempt aiming to expand the fi eld of the real and of the poetic has necessarily to refl ect on the means of communication to use.”1 Surrealism has always claimed to extend the domain of what is 1 “The Utility of Surrealist Editions and of the Surrealist Gallery: An Inquiry,” in Ce qui sera/What Will Be/Lo que serà: Almanac of the International Surrealist Movement, “hors- série” number of Brumes Blondes, ed. Her de Vries and Laurens Vancrevel (Amsterdam: Brumes Blondes, 2014), 438–39. -

UNIT 1 - Women’S Writing – SHS5012

SCHOOL OF SCIENCE AND HUMANITIES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH UNIT 1 - Women’s Writing – SHS5012 0 1. Juliet Mitchell, “Femininity, Narrative and Psychoanalysis” In Juliet Mitchell’s essay, “Femininity, Narrative and Psychoanalysis,” Mitchell examines the role that the novel has played in our capitalist society for women and the influence of psychoanalytic motives for writing the novel to prove that the novel was, and perhaps still is, the defining element of women in our society. Mitchell’s essay addresses more than a single topic. All of her topics are link together, though, as Mitchell places each topic as a constraint around the identity of the women in society. In terms of language, the woman is constrained because language is a masculine language. In a capitalist society, the woman is constrained by the bourgeois roles expected of women. And finally, and perhaps most importantly, from a psychoanalytic perspective, the woman is constrained by the resulting masculine or not-masculine society derived from pre-Oedipal childhood (I think). The combination of these constraints ways down upon the women and results in a feminist movement that simultaneously rejects masculine society, while adhering to its rules. The novel is, in Mitchell’s words, “the prime example of the way women start to create themselves as social subjects under bourgeois capitalism.” After finishing Mitchell’s essay, I couldn’t tell if she was opposed to the novel, which I think is an important point to clarify, as Mitchell herself asserts the novel as the defining element for women in a capitalist society. Perhaps she is in favor of novels that are critical, such as a main subject her essay, Wuthering Heights, and not for conformist novels, such as those by Mills and Boon. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 284 2nd International Conference on Art Studies: Science, Experience, Education (ICASSEE 2018) Song Dynasty Gate Structure and Its Typology Reflected in the Paintings of Chinese Artists of 10th– 13th Centuries* Marianna Shevchenko Moscow Institute of Architecture (State Academy) Scientific Research Institute of Theory and History of Architecture and Urban Planning Moscow, Russia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract—In Chinese architecture, gate structures have ranking system for government officials in Imperial China, always served as an indicator of the status of the owner and the different requirements to the forms of the gate structures of rank of the entire complex. Unfortunately, since the time of the their residences have emerged. According to the rank system Song Dynasty very few gates have been preserved up to the of the Tang dynasty (618-907 A.D.), government officials of present day, and mostly they belong to the monastery gates. rank three or higher were allowed to build a three-bay gate However, Song dynasty paintings and frescoes show a well- structures covered with two-slope roofs of xuanshan (悬山) developed typology of the gates and diversity in form. Besides type [3]. A special room for the gatekeepers could be different constructive and decorative elements, used in the arranged behind the gates of particularly large residences. Song dynasty gates structures are presented in detail in Song One family could have several high rank court officials. In paintings. The analysis of the depiction of the entrance this case behind the residence’s main gates the additional buildings on the scrolls and the frescoes of the 10 th –13th centuries allows us to expand existing understanding about the gates with a name of the official and his insignia were placed. -

Lecture Notes, by James Cahill

Lecture Notes, by James Cahill Note: The image numbers in these lecture notes do not exactly coincide with the images onscreen but are meant to be reference points in the lectures’ progression. Lecture 9B: Political and Poetic Themes in Southern Song Painting As we move into a period from which more reliable work survives, we can begin to address big concerns such as political themes in court painting, and poetic painting. The latter, poetic painting, means different things to different people; I myself gave a series of lectures that turned into a book titled The Lyric Journey: Poetic Painting in China and Japan (Harvard University Press, 1996). As I acknowledge in that book, there are a number of ways one can define poetic painting in China; I certainly donʹt claim that mine is the only right one, or even that itʹs the best way. In a broad sense, a lot of Southern Song Academy and academy‐style painting can be called poetic, either because it was done in response to couplets and quatrains of poetry presented to the artists by the emperor or others in the court, or simply because they knew that their imperial patrons preferred paintings that could be called poetic. I will develop that theme more as we move further into Southern Song painting; but I want to keep it always problematic, not a quality that one can define clearly or identify easily in paintings. Political Themes and Dynastic Restoration 9.13.1: The Virtuous Brothers Po‐I and Shu‐chʹi in the Wilderness Picking Herbs, early copy after Li Tang, handscroll, Palace Museum, Beijing. -

Spring and Autumn China (771-453)

Indiana University, History G380 – class text readings – Spring 2010 – R. Eno 1.7 SPRING AND AUTUMN CHINA (771-453) The history of the Spring and Autumn period was traditionally pictured as a narrative in which the major actors were states, their rulers, and certain high ministers and colorful figures. The narrative generally was shaped by writers to convey ethical points. It was, on the largest scale, a “true” story, but its drama was guided by a moral rationale. In these pages, we will survey the events of this long period. Our narrative will combine a selective recounting of major events with an attempt to illustrate the political variety that developed among the patrician states of the time. It embeds also certain stories from traditional sources, which are intended to help you picture more vividly and so recall more easily major turning points. These tales (which appear in italics) are retold here in a way that eliminates the profusion of personal and place names that characterize the original accounts. There are four such stories and each focuses on a single individual (although the last and longest has a larger cast of characters). The first two stories, those of Duke Huan of Qi and Duke Wen of Jin, highlight certain central features of Spring and Autumn political structures. The third tale, concerning King Ling of Chu, illustrates the nature of many early historical accounts as cautionary tales. The last, the story of Wu Zixu, is one of the great “historical romances” of the traditional annals. It is important to bear in mind that the tales recounted here are parts of a “master narrative” of early China, crafted by literary historians.