Economic Advantages of Bilingualism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Linguistic Profile of the Bilingual Visible Minority Population in Canada Prepared for the Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages

Linguistic Profile of the Bilingual Visible Minority Population in Canada Prepared for the Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages Fall 2007 Ce document est également offert en français. Overview The Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages (OCOL) works to ensure the implementation of the Official Languages Act. The Commissioner of Official Languages is required to take all actions and measures within his authority to ensure recognition of the status of each of the official languages and compliance with the spirit and intent of the Official Languages Act in the administration of the affairs of federal institutions, including any of their activities relating to the advancement of English and French in Canadian society. In order to obtain a general picture of the bilingual visible minority population in Canada, Government Consulting Services undertook for OCOL, an analysis using data from the 2001 Census of Canada carried out by Statistics Canada. The analysis looks at bilingualism and education levels of visible minorities and where visible minority populations are located in Canada. Particular attention is given to visible minorities between the ages of 20 and 49, the ideal age for recruitment into the work force. For the purposes of this study, the term "bilingual" refers to the two official languages of Canada. The term "Canadians" is used in this study to refer to people living in Canada, without regard to citizenship. It should be noted that 23% of the visible minority population residing in Canada are not Canadian -

The Vitality of Quebec's English-Speaking Communities: from Myth to Reality

SENATE SÉNAT CANADA THE VITALITY OF QUEBEC’S ENGLISH-SPEAKING COMMUNITIES: FROM MYTH TO REALITY Report of the Standing Senate Committee on Official Languages The Honourable Maria Chaput, Chair The Honourable Andrée Champagne, P.C., Deputy Chair October 2011 (first published in March 2011) For more information please contact us by email: [email protected] by phone: (613) 990-0088 toll-free: 1 800 267-7362 by mail: Senate Committee on Official Languages The Senate of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, K1A 0A4 This report can be downloaded at: http://senate-senat.ca/ol-lo-e.asp Ce rapport est également disponible en français. Top photo on cover: courtesy of Morrin Centre CONTENTS Page MEMBERS ORDER OF REFERENCE PREFACE INTRODUCTION .................................................................................... 1 QUEBEC‘S ENGLISH-SPEAKING COMMUNITIES: A SOCIO-DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE ........................................................... 4 QUEBEC‘S ENGLISH-SPEAKING COMMUNITIES: CHALLENGES AND SUCCESS STORIES ...................................................... 11 A. Community life ............................................................................. 11 1. Vitality: identity, inclusion and sense of belonging ......................... 11 2. Relationship with the Francophone majority ................................. 12 3. Regional diversity ..................................................................... 14 4. Government support for community organizations and delivery of services to the communities ................................ -

Language Planning and Education of Adult Immigrants in Canada

London Review of Education DOI:10.18546/LRE.14.2.10 Volume14,Number2,September2016 Language planning and education of adult immigrants in Canada: Contrasting the provinces of Quebec and British Columbia, and the cities of Montreal and Vancouver CatherineEllyson Bem & Co. CarolineAndrewandRichardClément* University of Ottawa Combiningpolicyanalysiswithlanguagepolicyandplanninganalysis,ourarticlecomparatively assessestwomodelsofadultimmigrants’languageeducationintwoverydifferentprovinces ofthesamefederalcountry.Inordertodoso,wefocusspecificallyontwoquestions:‘Whydo governmentsprovidelanguageeducationtoadults?’and‘Howisitprovidedintheconcrete settingoftwoofthebiggestcitiesinCanada?’Beyonddescribingthetwomodelsofadult immigrants’ language education in Quebec, British Columbia, and their respective largest cities,ourarticleponderswhetherandinwhatsensedemography,languagehistory,andthe commonfederalframeworkcanexplainthesimilaritiesanddifferencesbetweenthetwo.These contextualelementscanexplainwhycitiescontinuetohavesofewresponsibilitiesregarding thesettlement,integration,andlanguageeducationofnewcomers.Onlysuchunderstandingwill eventuallyallowforproperreformsintermsofcities’responsibilitiesregardingimmigration. Keywords: multilingualcities;multiculturalism;adulteducation;immigration;languagelaws Introduction Canada is a very large country with much variation between provinces and cities in many dimensions.Onesuchaspect,whichremainsacurrenthottopicfordemographicandhistorical reasons,islanguage;morespecifically,whyandhowlanguageplanningandpolicyareenacted -

Diversity, Democracy and Federalism: Issues, Options and Opportunities June 7-9, 2011 at Kathmandu, Nepal

Regional Conference on Diversity Theme: Diversity, Democracy and Federalism: issues, options and opportunities June 7-9, 2011 at Kathmandu, Nepal Key Note Speech and Canadian Model: Mr. Rupak Chattopadhyay, President and CEO Forum of Federations Good morning every one, and thank you Zafar and Katherine for a vey lucid words of welcome, I regret very much that this seminar is not in Islamabad, primarily because Nepal is a very active program country for the Forum of Federations, so I will be constantly pulled out of the seminar over the course of the next three days. I would have liked to stay through the entire program. Nevertheless, I am glad that we could put this together. As you all know that the Forum of Federations through its activities in Pakistan has been active on issues of diversity. Indeed the Forum itself was founded in Canada in 1999 in the context of a challenge to Canadian unity posed by its diversity in 1996. The separtist referendum in Quebec almost split the country. It was in that context that the government of Canada set up the Forum of Federations to bring together like minded countries grappling with the issues of unity and diversity. Countries who could sit around the table and share experiences on how they deal with the issue of diversity in their own context and share practices both best practices but also worst practices because we can learn as much from bad practices as we can from best practices. My remarks this morning will be in two parts. First, I will make some general observations about how federal structures respond to challenges posed by diversity in a comparative context and then, I will draw from the Canadian example to high light how we are coping with matters of diversity. -

Language Projections for Canada, 2011 to 2036

Catalogue no. 89-657-X2017001 ISBN 978-0-660-06842-8 Ethnicity, Language and Immigration Thematic Series Language Projections for Canada, 2011 to 2036 by René Houle and Jean-Pierre Corbeil Release date: January 25, 2017 How to obtain more information For information about this product or the wide range of services and data available from Statistics Canada, visit our website, www.statcan.gc.ca. You can also contact us by email at [email protected] telephone, from Monday to Friday, 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., at the following numbers: • Statistical Information Service 1-800-263-1136 • National telecommunications device for the hearing impaired 1-800-363-7629 • Fax line 1-514-283-9350 Depository Services Program • Inquiries line 1-800-635-7943 • Fax line 1-800-565-7757 Standards of service to the public Standard table symbols Statistics Canada is committed to serving its clients in a prompt, The following symbols are used in Statistics Canada reliable and courteous manner. To this end, Statistics Canada has publications: developed standards of service that its employees observe. To . not available for any reference period obtain a copy of these service standards, please contact Statistics .. not available for a specific reference period Canada toll-free at 1-800-263-1136. The service standards are ... not applicable also published on www.statcan.gc.ca under “Contact us” > 0 true zero or a value rounded to zero “Standards of service to the public.” 0s value rounded to 0 (zero) where there is a meaningful distinction between true zero and the value that was rounded p preliminary Note of appreciation r revised Canada owes the success of its statistical system to a x suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements long-standing partnership between Statistics Canada, the of the Statistics Act citizens of Canada, its businesses, governments and other E use with caution institutions. -

Official Language Bilingualism for Allophones in Canada: Exploring Future Research Callie Mady and Miles Turnbull

Official Language Bilingualism for Allophones in Canada: Exploring Future Research Callie Mady and Miles Turnbull This article offers a review of policy and research as they relate to Allophones and their access to French Second Official Language (FSOL) programs in English- dominant Canada. Possible areas of future research are woven throughout the re- view as questions emerge in the summary of relevant literature. Notre article comprend une recension des documents de politique et des projets de recherche concernant les Allophones inscrits aux programmes de français langue seconde et officielle (FLSO) au Canada. Tout au long de l’article, nous tis- sons une série de questions de recherche possible pour le futur comme elles ont émergé pendant le développement de la recension des écrits. The Canadian Constitution (Canada, Department of Justice, 1982) guaran- tees equal status to English and French as the official languages of Canada providing for federal government services in both languages. As such, many federal job opportunities at minimum are centered on official-language bilingualism. In addition to linguistic considerations, the federal govern- ment recognizes official-language bilingualism as vital to Canadian identity (Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages, 2006). The dual privileg- ing of English and French by way of commodity and identity (Heller, 2002), then, encourages immigrants to Canada to consider such proclamations as they establish themselves and reconstruct their identities (Blackledge & Pavlenko, 2001). As Canada moves forward with its agenda to promote linguistic duality and official-language bilingualism, it must consider the effect of the growing Allophone population. In 2000, former Commissioner of Official Languages Dyane Adam called for a clear research agenda relating to Allophones and language education in Canada; she recognized immigration as a challenge to official-language bilingualism (Office of the Commissioner of Official Lan- guages, 2000). -

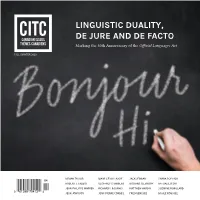

LINGUISTIC DUALITY, DE JURE and DE FACTO Marking the 50Th Anniversary of the Official Languages Act

LINGUISTIC DUALITY, DE JURE AND DE FACTO Marking the 50th Anniversary of the Official Languages Act FALL / WINTER 2019 MIRIAM TAYLOR DIANE GÉRIN-LAJOIE JACK JEDWAB SHANA POPLACK ROBERT J. TALBOT GEOFFREY CHAMBERS RICHARD SLEVINSKY NATHALIE DION JEAN-PHILIPPE WARREN RICHARD Y. BOURHIS MATTHEW HAYDAY SUZANNE ROBILLARD JEAN JOHNSON JEAN-PIERRE CORBEIL FRED GENESEE BASILE ROUSSEL TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 INTRODUCTION SECTION 3 – THE STATE OF BILINGUALISM: CANADA’S OFFICIAL LANGUAGES ACT AT 50: FACTS, FIGURES AND WAYS FORWARD BILINGUALISM, PLURALISM AND IDENTITIES 34 THE EVOLUTION OF FRENCH-ENGLISH Miriam Taylor BILINGUALISM IN CANADA OVER THE PAST SECTION 1 – IDENTITY AND POLITICS 50 YEARS: A REFLECTION OF THE EVOLUTION OF RELATIONS BETWEEN FRENCH AND 6 WHY LINGUISTIC DUALITY STILL MATTERS, ENGLISH-SPEAKING CANADIANS? 50 YEARS AFTER THE OLA: AN ANGLOPHONE Jean-Pierre Corbeil MAJORITY PERSPECTIVE Robert J. Talbot 39 BONJOUR, HI AND OLA With a foreword from Raymond Théberge, Commissioner Jack Jedwab of Official Languages of Canada SECTION 4 – LANGUAGE EDUCATION: OVERVIEW AND CHALLENGES 12 THE PRIME MINISTER OF A BILINGUAL COUNTRY MUST BE BILINGUAL 44 THE EVOLUTION OF FRENCH LANGUAGE Jean-Philippe Warren TERMINOLOGY IN THE FIELD OF EDUCATION FROM CONFEDERATION THROUGH TO THE SECTION 2 – MINORITY VOICES: THE EVOLUTION AND PRESENT DEFENSE OF MINORITY LANGUAGE COMMUNITIES Richard Slevinsky 17 50 YEARS AFTER FIRST OFFICIAL LANGUAGES ACT, THE STATUS OF FRENCH IN CANADA IS RECEDING 48 CAUGHT IN A TIMELOOP: 50 YEARS OF Jean Johnson REPEATED CHALLENGES FOR -

Designing Names: Requisite Identity Labour for Migrants’ Be(Long)Ing in Ontario

Designing Names: Requisite Identity Labour for Migrants’ Be(long)ing in Ontario by Diane Yvonne Dechief A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Information University of Toronto © Copyright by Diane Yvonne Dechief 2015 Designing Names: Migrants’ Identity Labour for Be(long)ing in Ontario Diane Yvonne Dechief Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Information University of Toronto 2015 Abstract This dissertation responds to the question of why people who immigrate to Ontario, Canada frequently choose to use their personal names in altered forms. Between May and December 2010, I engaged in semi-structured interviews with twenty-three people who, while living in Ontario, experienced name challenges ranging from persistent, repetitive misspellings and mispronunciations of their original names to cases of significant name alterations on residency documents, and even to situations of exclusion and discrimination. Drawing on critical perspectives from literature on identity and performativity, science and technology studies, race and immigration, affect, and onomastics (the study of names), I establish that name challenges are a form of “identity labour” required of many people who immigrate to Ontario. I also describe how individuals’ identity labour changes over time. In response to name challenges, and the need to balance between their sometimes-simultaneous audiences, participants design their names for life in Ontario—by deciding which audiences to privilege, they choose where they want to belong, and how their names should be. ii Acknowledgments Thank you very, very much to this study’s participants. You were so generous with your stories, and you articulated your thoughts and your concerns in such novel and passionate ways. -

Canada Du FCFA

FCFA du Canada du FCFA 2nd Edition 2nd Canada Community Profile Profile Community of Acadian Francophone and and 2nd Edition Canada Canada 2e édition Profil des communautés francophones et acadiennes du Canada 2e édition FCFA du Canada www.fcfa.ca : Web Site and International Trade International and et du Commerce international international Commerce du et Department of Foreign Affairs Foreign of Department Ministère des Affaires étrangères Affaires des Ministère [email protected] : Courriel (613) 241-6046 (613) : Télécopieur (613) 241-7600 (613) : Téléphone Heritage canadien Canadian Patrimoine Ottawa (Ontario) K1N 5Z4 K1N (Ontario) Ottawa 450, rue Rideau, bureau 300 bureau Rideau, rue 450, possible grâce à l’appui financier du : : du financier l’appui à grâce possible et acadienne (FCFA) du Canada Canada du (FCFA) acadienne et La publication de ce profil a été rendue rendue été a profil ce de publication La La Fédération des communautés francophones francophones communautés des Fédération La Dépôt légal - Bibliothèque nationale du Canada du nationale Bibliothèque - légal Dépôt 2-922742-21-0 : ISBN © Mars 2004 Mars © Corporate Printers Ltd. Printers Corporate : Impression GLS dezign Inc. dezign GLS : graphique Conception Joelle Dubois, Isabelle Lefebvre, Micheline Lévesque (mise à jour) à (mise Lévesque Micheline Lefebvre, Isabelle Dubois, Joelle Michel Bédard, Karine Lamarre (première édition), Tina Desabrais, Tina édition), (première Lamarre Karine Bédard, Michel : production la à Appui Micheline Doiron (première édition), Robin -

Canadian Bilingualism, Multiculturalism and Neo- Liberal Imperatives

Scholars Speak Out December 2016 Canadian Bilingualism, Multiculturalism and Neo- Liberal Imperatives By Douglas Fleming, University of Ottawa Canadian second language and immigration policies have often been held up as positive models for Americans on both the right and the left. In particular, both the “English Only” and the “English Plus” movements in the United States have claimed that French Immersion programming in Canada support their own positions (Crawford, 1992; King, 1997). However, in this piece I argue that Canadian immigration and language policies are closely intertwined and have been carefully calculated to subsume linguistic and cultural diversity under what Young (1987) once characterized as a form of “patriarchal Englishness against and under which… all others are subordinated” (pp.10-11). These policies have served neo-liberal economic imperatives and have helped perpetuate inequalities. In fact, I am of the opinion that they are not incompatible with empire building. Bilingualism and Multiculturalism Canada is a nation in which French is the first language for 22% of the total population of 36 million. English is the first language for 59%. The remaining 19% speak a third language as their mother tongue. The size of this third language grouping (the so-called Allophones) is due mainly to immigration (the highest rate in the G8 industrialized nations), self- reported visible minority status (19%) and the relatively high numbers of first nation peoples (4.5%). According to the last census, 17.5 % of the total population is now bilingual and 26.5% born outside of the country. It is a highly diverse population (all figures, Statistics Canada, 2016). -

Government of Nunavut Observations on the Role of Languages and Culture in the Promotion and Protection of the Rights and Identity of Inuit

OHCHR Indigenous Language and Culture Study – Submission of the Territory of Nunavut, Canada Government of Nunavut observations on the role of languages and culture in the promotion and protection of the rights and identity of Inuit Submission 1. The Government of Nunavut appreciates the opportunity to share its views on “the role of languages and culture in the promotion and protection of the rights and identity of indigenous people” in Nunavut, Canada as requested by the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) in its communications dated 4 November 2011. The Government of Nunavut understands that the OHCHR is seeking information on this matter, in accordance with Human Rights Council (HRC) resolution 18/8, in support of the Expert Mechanism’s study, which the Mechanism will present to the HRC at its 21st session. 2. As with all languages, the indigenous languages of Canada’s newest territory, Nunavut, operate as the fundamental medium of personal and cultural expression through which Inuit knowledge, values, history, tradition and identity are transmitted. In Nunavut, the Inuit Language (comprised of Inuktitut and Inuinnaqtun) also carries with it a significant legal and political dialogue that represents the protection of the rights of Inuit people. 3. In particular, the Inuit Language constitutes the banner under which the indigenous people of Nunavut exercise their right, reflected in Article 5 of UNDRIP, to “maintain and strengthen their distinct political, legal, economic, social and cultural institutions, while retaining their right to participate fully, if they so choose, in the political, economic, social and cultural life of the State.” The Inuit Language also acts as the vehicle through which Indigenous peoples are able to exercise their right to revitalize, use, develop and transmit to future generations their histories, oral traditions, philosophies, writing systems and literatures, and to designate and retain their own names for communities, places and persons” pursuant to UNDRIP, Article 13. -

The History and Current Status of the Instruction of Spanish As a Heritage Language in Canada Florencia Carlino

Document généré le 1 oct. 2021 04:27 International Journal of Canadian Studies Revue internationale d’études canadiennes The History and Current Status of the Instruction of Spanish as a Heritage Language in Canada Florencia Carlino Borders, Migrations and Managing Diversity: New Mappings Frontières, migrations et gestion de la diversité : nouvelles cartographies Numéro 38, 2008 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/040817ar DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/040817ar Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) Conseil international d'études canadiennes ISSN 1180-3991 (imprimé) 1923-5291 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cette note Carlino, F. (2008). The History and Current Status of the Instruction of Spanish as a Heritage Language in Canada. International Journal of Canadian Studies / Revue internationale d’études canadiennes, (38), 263–277. https://doi.org/10.7202/040817ar Tous droits réservés © Conseil international d'études canadiennes, 2008 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ Florencia Carlino1 The History and Current Status of the Instruction of Spanish as a Heritage Language in Canada2 Spanish as a heritage language (SHL) is a well-recognized field of study and practice in the United States3.