To Read a PDF-Chapter About Robert and Ludvig

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Granting the Nobel Prize to the European Union Is in Violation of Alfred Nobel’S Will

The EU is not a “Person”: Granting the Nobel Prize to the European Union is in Violation of Alfred Nobel’s Will By Prof Michel Chossudovsky Region: Europe Global Research, October 13, 2012 Theme: Law and Justice This year’s Nobel Peace Prize was granted to the European Union (EU) for its relentless contribution to “the advancement of peace and reconciliation, democracy and human rights in Europe.” While the EU’s contribution to peace is debatable, the key issue is whether a union of nation states, which constitutes a political, economic, monetary and fiscal entity is an “eligible candidate” for the Peace Prize, in accordance with the mandate of the Norwegian Committee. The Olympic Games are “granted” to countries. But the Nobel Peace Prize cannot under any stretch of the imagination be granted to a nation-state, let alone a union of nation states. The Norwegian Nobel Committee has a responsibility to ascertain “the eligibility of candidates” in accordance with the Will of Alfred Bernhard Nobel Paris,( 27 November, 1895). “The whole of my remaining realizable estate shall be dealt with in the following way: the capital, invested in safe securities by my executors, shall constitute a fund, the interest on which shall be annually distributed in the form of prizes to those who, during the preceding year, shall have conferred the greatest benefit to mankind…. The said interest shall be divided into five equal parts, which shall be apportioned as follows: one part to the person who shall have made the most important discovery or invention within -

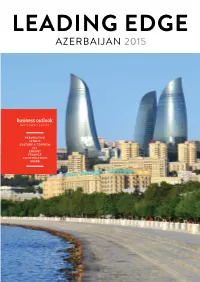

Azerbaijan Investment Guide 2015

PERSPECTIVE SPORTS CULTURE & TOURISM ICT ENERGY FINANCE CONSTRUCTION GUIDE Contents 4 24 92 HE Ilham Aliyev Sports Energy HE Ilham Aliyev, President Find out how Azerbaijan is The Caspian powerhouse is of Azerbaijan talks about the entering the world of global entering stage two of its oil future for Azerbaijan’s econ- sporting events to improve and gas development plans, omy, its sporting develop- its international image, and with eyes firmly on the ment and cultural tolerance. boost tourism. European market. 8 50 120 Perspective Culture & Finance Tourism What is modern Azerbaijan? Diversifying the sector MICE tourism, economic Discover Azerbaijan’s is key for the country’s diversification, international hospitality, art, music, and development, see how relations and building for tolerance for other cultures PASHA Holdings are at the future. both in the capital Baku the forefront of this move. and beyond. 128 76 Construction ICT Building the monuments Rapid development of the that will come to define sector will see Azerbaijan Azerbaijan’s past, present and future in all its glory. ASSOCIATE PUBLISHERS: become one of the regional Nicole HOWARTH, leaders in this vital area of JOHN Maratheftis the economy. EDITOR: 138 BENJAMIN HEWISON Guide ART DIRECTOR: JESSICA DORIA All you need to know about Baku and beyond in one PROJECT DIRECTOR: PHIL SMITH place. Venture forth and explore the ‘Land of Fire’. PROJECT COORDINATOR: ANNA KOERNER CONTRIBUTING WRITERS: MARK Elliott, CARMEN Valache, NIGAR Orujova COVER IMAGE: © RAMIL ALIYEV / shutterstock.com 2nd floor, Berkeley Square House London W1J 6BD, United Kingdom In partnership with T: +44207 887 6105 E: [email protected] LEADING EDGE AZERBAIJAN 2015 5 Interview between Leading Edge and His Excellency Ilham Aliyev, President of the Republic of Azerbaijan LE: Your Excellency, in October 2013 you received strong reserves that amount to over US $53 billion, which is a very support from the people of Azerbaijan and were re-elect- favourable figure when compared to the rest of the world. -

The Emergence of the French Oil Industry Between the Two Wars

The Emergence of the French Oil Industry between the Two Wars Mohamed Sassi The late emergence of a French oil industry, precisely between the two wars, at first appears to be an economic miracle. It was born from a determination to set up an independent energy policy. France is a country deprived of natural resources and, on the eve of the First World War, its vital need for energy pushed it to give more importance to oil, which explains private initiatives such as the case of Desmarais Frères. In 1914, the French supply of oil was totally dependant on the Majors, particularly on the American company Standard Oil. Although from 1917 Shell was privileged, the problem of the oil industry was not yet resolved. In 1919, the French objective was to recover a part of the interests of the Turkish Petroleum Company (T.P.C.) in the Near East. France recovered the share of the Deutsche Bank and thus created the Compagnie Française des Pétroles (C.F.P.). Born in 1924, the company was to be associated with any preexisting French oil company in order to assure an indisputable majority of national capital. The second important step was the setting-up of the law of 1928 that took care of special export authorizations of the crude and refined oils. The final step was the creation of the refining company (C.F.R.). The state supported the development of the C.F.P. by some institutional arrangements and succeeded in integrating it upstream, by adding the capital of the largest distribution companies and by encouraging the development of their distribution activity. -

Utvikling Av Lokale Foretak I Oljesektoren I Aserbajdsjan

Utvikling av lokale foretak i oljesektoren i Aserbajdsjan Hilde Solli Hovedoppgave i samfunnsgeografi Institutt for sosiologi og samfunnsgeografi Universitetet i Oslo februar 2005 Utvikling av lokale foretak i oljesektoren i Aserbajdsjan Hilde Solli Hovedoppgave i samfunnsgeografi Institutt for sosiologi og samfunnsgeografi Universitetet i Oslo februar 2005 Forsidefoto, gamle oljetårn i området rundt Baku. Hilde Solli 2 Forord Jeg vil gjerne takke de som har bidratt med inspirasjon, hjelp og støtte i arbeidet med hovedoppgaven. Takk til veilederne mine Tone Haraldsen og Hege Knutsen. Tone har bidratt med å kreve teoretisk grundighet i startfasen. En spesiell takk til Hege som har hjulpet meg i sluttfasen med oppgaven og som har kommet med så mange konstruktive innspill. Jeg vil takke Pål Eitrheim og Jamila Gadijeva i Statoil Aserbajdsjan for god hjelp i planlegging av feltarbeidet og praktisk hjelp under oppholdet i Baku. Jeg vil også takke den norske ambassaden i Baku for hjelp og støtte. En spesiell takk til Thea som gjorde oppholdet mitt i Baku mye hyggeligere enn det ellers ville ha vært. Takk til Torleif og Tarana Nilsen for praktisk hjelp med blant annet bosetning i Baku. Takk til BP, BP Enterprisesenter, Business Development Alliance, Maritime Hydrolics, Eupec, McDermott, Janubsanayetikinti, MCG, REM Services og RISK Company for intervjuer og omvisning på verkstedsområder. Takk for at dere satt av tid til intervjuet og hjalp meg videre i prosessen. Takk til institutt for sosiologi og samfunnsgeografi for økonomisk støtte til feltarbeidet. Takk til kollokviegruppen min Anja, Yohan, Steinar og Camilla for at dere leste tidlige utkast av oppgaven min og for at dere har vært med å diskutere teoretiske tilnærminger. -

Companies Involved in Oilfield Services from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Companies Involved in Oilfield Services From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Diversified Oilfield Services Companies These companies deal in a wide range of oilfield services, allowing them access to markets ranging from seismic imaging to deep water oil exploration. Schlumberger Halliburton Baker Weatherford International Oilfield Equipment Companies These companies build rigs and supply hardware for rig upgrades and oilfield operations. Yantai Jereh Petroleum Equipment&Technologies Co., Ltd. National-Oilwell Varco FMC Technologies Cameron Corporation Weir SPM Oil & Gas Zhongman Petroleum & Natural Gas Corpration LappinTech LLC Dresser-Rand Group Inc. Oilfield Services Disposal Companies These companies provide saltwater disposal and transportation services for Oil & Gas.. Frontier Oilfield Services Inc. (FOSI) Oil Exploration and Production Services Contractors These companies deal in seismic imaging technology for oil and gas exploration. ION Geophysical Corporation CGG Veritas Brigham Exploration Company OYO Geospace These firms contract drilling rigs to oil and gas companies for both exploration and production. Transocean Diamond Offshore Drilling Noble Hercules Offshore Parker Drilling Company Pride International ENSCO International Atwood Oceanics Union Drilling Nabors Industries Grey Wolf Pioneer Drilling Co Patterson-UTI Energy Helmerich & Payne Rowan Companies Oil and Gas Pipeline Companies These companies build onshore pipelines to transport oil and gas between cities, states, and countries. -

BRANOBEL HISTORY PROJECT NEWSLETTER NO. 2, 11 OCT. 2010 Sponsored by Stiftelsen Olle Engkvist Byggmästare

BRANOBEL HISTORY PROJECT NEWSLETTER NO. 2, 11 OCT. 2010 sponsored by stiftelsen olle engkvist byggmästare. Azerbaijani archives’ delegation After launching our first newsletter three months ago the Branobel History Project has made important progress. By now, we are actually designing and developing the new in- ternational website that will make historical source material widely available for research on the fascinating oil industry of the Nobel brothers in Azerbaijan 1873-1922. In parallel with that, a special database is being assembled for hosting the The Centre for Business History in Stockholm (CBHS) multitude of digital documents that will soon become easily preserves and presents the business history of Sweden. We handle the archives and photos of more than seven and safely accessible via Internet. thousand Sweden-based companies from 1740 to the present. The CBHS has taken a lead in presenting his- The partnership between CBHS and the National Archives tory, for example in producing historical websites for of Azerbaijan has deepened and strengthened. During the several companies and transnational corporations, the first week of September a top level Azerbaijani archives’ most recent one being www.ericssonhistory.com that delegation headed by Dr. Atakhan Pashayev, Director of Na- attracts some 25.000 visitors monthly. For more infor- mation about CBHS, visit www.naringslivshistoria.se tional Board of Archives of the Azerbaijan Republic, visited Stockholm for project discussions upon invitation by the The National Board of Archives of Centre for Business History. Dr. Pashayev was accompanied Azerbaijan Republic represents 79 ar- by Dr. Anar Mammadov, Deputy Director of the National chives all across Azerbaijan, of which History Archive in Baku, and Mr. -

Memory of the World – Världsminnesprogrammet

En introduktion till Memory of the World – Världsminnesprogrammet SVENSKA. UNESCORÅDETS. 1/2012 SKRIFTSERIE En introduktion till Memory of the World – Världsminnesprogrammet United Nations Världsminnesprogrammet Educational, Scientific and Memory of the World Cultural Organization Innehåll Svenska unescorådets årsbok 2011 Förord..............................................................................................7 Svenska unescorådets skriftserie, nr 1/2012 Världsminnesprogrammet.i.Sverige.......................................................8 unesco Inledning........................................................................................10 Unesco är Förenta nationernas organisation för utbildning, vetenskap, kultur och kommunikation. Unescos mål är att bidra till fred och säkerhet genom Alfred.Nobels.familjearkiv..................................................................23 internationellt samarbete inom dessa ansvarsområden. Unesco grundades år 1945, har 195 medlemsländer och sekretariat i Paris. Sverige blev Ingmar.Bergmans.Arkiv.....................................................................31 medlem år 1951. Astrid.Lindgrens.Arkiv.......................................................................39 Mer information om Unesco: www.unesco.org Stockholms.stads.byggnadsritningar....................................................49 SvEnSka unescorådEt Codex.argenteus..............................................................................57 Svenska Unescorådet ger råd till den svenska regeringen när -

Alfred Nobel and His Prizes: from Dynamite to DNA

Open Access Rambam Maimonides Medical Journal NOBEL PRIZE RETROSPECTIVE AFTER 115 YEARS Alfred Nobel and His Prizes: From Dynamite to DNA Marshall A. Lichtman, M.D.* Department of Medicine and the James P. Wilmot Cancer Institute, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY, USA ABSTRACT Alfred Nobel was one of the most successful chemists, inventors, entrepreneurs, and businessmen of the late nineteenth century. In a decision later in life, he rewrote his will to leave virtually all his fortune to establish prizes for persons of any nationality who made the most compelling achievement for the benefit of mankind in the fields of chemistry, physics, physiology or medicine, literature, and peace among nations. The prizes were first awarded in 1901, five years after his death. In considering his choice of prizes, it may be pertinent that he used the principles of chemistry and physics in his inventions and he had a lifelong devotion to science, he suffered and died from severe coronary and cerebral atherosclerosis, and he was a bibliophile, an author, and mingled with the literati of Paris. His interest in harmony among nations may have derived from the effects of the applications of his inventions in warfare (“merchant of death”) and his friendship with a leader in the movement to bring peace to nations of Europe. After some controversy, including Nobel’s citizenship, the mechanisms to choose the laureates and make four of the awards were developed by a foundation established in Stockholm; the choice of the laureate for promoting harmony among nations was assigned to the Norwegian Storting, another controversy. -

Alfred Nobel: Inventor, Entrepreneur and Industrialist (1833–1896)

A TRIBUTE TO THE MEMORY OF ALFRED NOBEL: INVENTOR, ENTREPRENEUR AND INDUSTRIALIST (1833–1896) Cover illustration: It is significant that the only existing portrait of Alfred Nobel was painted posthumously. Nobel, shy and busy as he was, had neither the inclination nor the time to sit for a portrait. Oil painting by Emil Österman 1915. (The Nobel Foundation) BY SVA N T E LINDQVIST ROYAL SWEDISH ACADEMY OF ENGINEERING SCIENCES (IVA) IVA-M 335 • ISSN 1102-8254 • ISBN 91-7082-681-1 A TRIBUTE TO THE MEMORY OF A LFRED NOBEL: INVENTOR, ENTREPRENEUR AND INDUSTRIALIST (1833–1896) 1 PRESENTED AT THE 2001 ANNUAL MEETING OF THE ROYAL SWEDISH ACADEMY OF ENGINEERING SCIENCES BY SVANTE LINDQVIST The Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering Sciences (IVA) is an independent, learned society whose main objectives are to promote the engineering and economic sciences, and to further the development of commerce and industry. In cooperation with the business 2 and academic communities, the Academy initiates and proposes measures that will strengthen Sweden’s industrial skills base and competitiveness. For further information, please visit IVA’s web site: www.iva.se. Published by the Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering Sciences (IVA) and Svante Lindqvist, 2001 IVA, P.O. Box 5073, SE-102 42 Stockholm, Sweden Telephone: Int +46 8 791 29 00 Fax: Int +46 8 611 56 23 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.iva.se IVA-M 335 • ISSN 1102-8254 • ISBN 91-7082-681-1 Translation by Bernard Vowles, 2001 Layout and production by Hans Melcherson, Tryckfaktorn AB, Stockholm, Sweden Printed in Sweden by OH-Tryck, Stockholm, Sweden, 2001 P REFACE Each year the Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering Sciences (IVA) produces a book- let commemorating a person whose scientific, engineering, economic or industrial achieve- ments were of significant benefit to the society of his or her day. -

Nobel Brothers’ “ Life

European Scientific Journal December 2013 /SPECIAL/ edition vol.2 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 THE ROLE OF AZERBAIJAN OIL IN “ NOBEL BROTHERS’ “ LIFE Tarana Mirzayeva, Doctorant Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences / Azerbaijan Republic, Baku Abstract The detailed information was given about the famous “Nobel Brothers” who invested capital to having fertile oil reserves Azerbaijan in XIX century in the text. As it is known,possessing oil deposit of Azerbaijan attracted the attention of foreign investors. The investors became the oil magnats of the periods thanks to Azerbaijan oil getting a large amount of oil capitals. One of such oil magnats was “Nobel Brothers” by origin Swiss. The Nobels were four brothers. Emil, Ludvig, Robert and Alfred Nobel. In 1875 the Nobels founded their own company buying a little area,and then turned this company to the “Nobel Brothers Oil Production Society” company in 18 may 1879. The activities of company involved almost all spheres of oil industry:oil research, production, refining, transportation etc. “Nobel Brothers” got leadership for developing of oil industry in Baku thanks to strong competition. Especially, in Russian bazaar they possessed representatives and depots for the purpose of transportation of much needed gas field in some cities of Russia(Charchin, Saratov, Babrusk, Nizhny-Novgorod, Perm etc.), as well as, in various Europe cities (Geneva, Hamburg, London and Manchester etc.) “Nobel Brothers” worked for achieving significant success in all directions of oil business consulting with outstanding oil-chemists scientists (D.I.Mendeleyev, K.I.Lisenko, L.Q.Qurvich and engineers A.V.Bari, V.Q.Shuchov and others). -

Nobel Prize Roots in Russia

Nobel Prize roots in Russia Tatiana Antipova [ 0000-0002- 0872-4965] Institute of Certified Specialists, Perm, Russia https://doi.org/10.33847/2712-8148.1.1_4 Abstract. The scientist who does not dream of receiving the Nobel Prize is unthinkable. The main reason for this research is that fact that just about 2,5% of Nobel Prize winners are Russians. This paper analyzed archive and literature documents about the activity of Alfred Nobel in Russia. In 1879 three Nobel Brothers (including Alfred) founded the "Nobel Brothers Association", abbreviated as Branobel, in Russia. Success touched Alfred Nobel’s fut in Russian business and part of his profit was secured in Russian Central Bank as we know from Alfred Nobel’s will. As a result of current research author tried to evaluate contribution of A. Nobel’s Russian business in Nobel Foundation and Russian life. Consequently, it was revealed that A. Nobel’s executor Sohlman R. stated that in the assets of the Nobel Prize the originally share of funds received from Branobel activities was about 12%. Keywords: Nobel Prize, Branobel, Petroleum Company, imperial Russia, oil production, oil storage, oil trade, Alfred Nobel, Nobel’s will. 1. Introduction Nobel Prize is the most prestigious prize among scientists worldwide. Between 1901 and 2019, the Nobel Prizes and the Prize in Economic Sciences were awarded 597 times to 950 people and organizations [1]. Thereof, twenty-four Russians won Nobel Prizes: two in Physiology or Medicine, twelve in Physics, one in Chemistry, two in Economic Sciences, five in Literature, and two Peace Prizes [2]. So just about 2,5% of Nobel Prize winners are Russians. -

:Il:::::::.:.T*I:{I$Í*$:::.[:T:'*:;Íj;A*;::I##' (16) "'Rk Mat a Law Wil (Rzl1"" Il';;# of Abracadabra

.:É E3 ffi-_1"-*. -E . Nyelvisrneret f_tl. j;!"'T.-il[ perc alaft végeztem writing a feladatokkal ;T !"JT."",;:.by a suitab'e Word frnl 10n(o)iu;,;""iJ;*;***k,=3.ili:*"":*""l:trJ,:tT,:ifi;* sale of tovs uri+L ^r-., , .J"oo."'" meals i"* ih;;;""ü ri*l..r," ;1;jfi"Ij::..J'..en,s ",;.;:#i:..";::|]] " i rruit reduced needed to (2) vegetab'"r.T:::::tvegetabres avoici ,"..:::,1l"clude rhe vo're,Ji'.'".*-{t) ';;il I ;:::il ;JllT:i:i T::::$.*u"",i1' -;:::; incen,ive ,,* :-] Lffii:1'r "her ":1T,TJ;::il:*:";"::,*"*n,s mav sive u, *."0. T;:ffi':j.J ; ;:; :::TT,,T1T:::::H-....vq rll tturs' seeds, eggs u€IlV€dffi : :,'.'''',''', : ; added.,, ffi or lT*]ow-fat i:f:::: cheese. (7 i:Tl.j:,uo- o.u."*errLrsr vitt-lvesatives i; Inn (B)(BJ j ; beverapesbeverages' 35?q per bebt ^^,-cent of ............ r ' 1'1(9r totarwL<7t caloriescarories sweeteners' can comecol from fat, and 10 per cent from added meals quarters 'n" must of a cup o.on' :;";":i: :::":'il1ffil;"#'f frui'f and'fhree. i:,:r;H:::*i3;'-ff: """;; Backers,;:il:::::::.:.T*i:{i$Í*$:::.[:T:'*:;Íj;a*;::i##' (16) "'rK mat a law wil (rzl1"" il';;# of abracadabra. , will help """' (:E(18) a to shift . boosrboost for11 the incentives chitdren,s heatrh away fror_ ;;_:nt*n s berieve that fat' salt and """""" (1el ..,.,....... .. shourd sugar;-"d;';:;"ut"* _.ro) be .-:..T::::.1:*1'r'.'"::.""T:ffiT;::".lthvchoices;;even." 0 In about;:-l l!_ and Iess another lot =_as of _______awav on rack other i can ought don't tE! from the nave there !q*"=-"* was lÍ which 6.