The Greensboro Four: Taking a Stand by Taking a Seat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greensboro Sit-Ins

Published on NCpedia (https://www.ncpedia.org) Home > Greensboro Sit-Ins Greensboro Sit-Ins [1] Share it now! Greensboro Sit-Ins by Alexander R. Stoesen, 2006 See also: Greensboro Four [2], Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee [3]. Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, Billy Smith and Clarence Henderson. Greensboro News and Record. The Greensboro [4] sit-ins of February 1960 launched the movement to integrate lunch counters and other eating establishments throughout North Carolina and the rest of the South. Sit-ins [5] had previously occurred in other places, but the Greensboro protests sparked widespread activism and media attention. The sit-ins began when four students from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University [6]—Ezell A. Blair [7] (now Jibreel Khazan), Franklin E. McCain [8], Joseph A. McNeil [9], and David L. Richmond [10]—sat at the lunch counter of the Woolworth Store on Elm Street in Greensboro late on the afternoon of 1 Feb. 1960. At the time, Woolworth's only served African Americans [11] at a stand-up counter. Instead of having the students arrested for trespassing, the manager closed the lunch counter, intending to leave them stranded at closing time. The Greensboro store, one of the most profitable in the region, had a large black clientele-hence the need for prudence. However, by not filing charges, the manager left an opening for further nonviolent action. The next day, the number of demonstrators grew rapidly, and in the days and weeks that followed, sit-ins spread to other eating places in Greensboro's central business district. Some managers closed their operations, but by the end of the summer an agreement had been reached to end segregation [12] in public eating places. -

Have a Seat to Be Heard: the Sit-In Movement of the 1960S

(South Bend, IN), Sept. 2, 1971. Have A Seat To Be Heard: Rodgers, Ibram H. The Black Campus Movement: Black Students The Sit-in Movement Of The 1960s and the Racial Reconstih,tion ofHigher Education, 1965- 1972. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. "The Second Great Migration." In Motion AAME. Accessed April 9, E1~Ai£-& 2017. http://www.inmotion.org/print. Sulak, Nancy J. "Student Input Depends on the Issue: Wolfson." The Preface (South Bend, IN), Oct. 28, 1971. "If you're white, you're all right; if you're black, stay back," this derogatory saying in an example of what the platform in which seg- Taylor, Orlando. Interdepartmental Communication to the Faculty regation thrived upon.' In the 1960s, all across America there was Council.Sept.9,1968. a movement in which civil rights demonstrations were spurred on by unrest that stemmed from the kind of injustice represented by United States Census Bureau."A Look at the 1940 Census." that saying. Occurrences in the 1960s such as the Civil Rights Move- United States Census Bureau. Last modified 2012. ment displayed a particular kind of umest that was centered around https://www.census.gov/newsroom/cspan/194ocensus/ the matter of equality, especially in regards to African Americans. CSP AN_194oslides. pdf. More specifically, the Sit-in Movement was a division of the Civil Rights Movement. This movement, known as the Sit-in Movement, United States Census Bureau. "Indiana County-Level Census was highly influenced by the characteristics of the Civil Rights Move- Counts, 1900-2010." STATSINDIANA: Indiana's Public ment. Think of the Civil Rights Movement as a tree, the Sit-in Move- Data Utility, nd. -

Civil Rights Activism in Raleigh and Durham, North Carolina, 1960-1963

SUTTELL, BRIAN WILLIAM, Ph.D. Campus to Counter: Civil Rights Activism in Raleigh and Durham, North Carolina, 1960-1963. (2017) Directed by Dr. Charles C. Bolton. 296 pp. This work investigates civil rights activism in Raleigh and Durham, North Carolina, in the early 1960s, especially among students at Shaw University, Saint Augustine’s College (Saint Augustine’s University today), and North Carolina College at Durham (North Carolina Central University today). Their significance in challenging traditional practices in regard to race relations has been underrepresented in the historiography of the civil rights movement. Students from these three historically black schools played a crucial role in bringing about the end of segregation in public accommodations and the reduction of discriminatory hiring practices. While student activists often proceeded from campus to the lunch counters to participate in sit-in demonstrations, their actions also represented a counter to businesspersons and politicians who sought to preserve a segregationist view of Tar Heel hospitality. The research presented in this dissertation demonstrates the ways in which ideas of academic freedom gave additional ideological force to the civil rights movement and helped garner support from students and faculty from the “Research Triangle” schools comprised of North Carolina State College (North Carolina State University today), Duke University, and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Many students from both the “Protest Triangle” (my term for the activists at the three historically black schools) and “Research Triangle” schools viewed efforts by local and state politicians to thwart student participation in sit-ins and other forms of protest as a restriction of their academic freedom. -

Congressional Record—House H572

H572 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE January 28, 2020 regulated. Ninety-nine percent of The four young men—Ezell Blair, Jr.; ing Woolworth’s and other establish- Pennsylvania was swept under these David Richmond; Franklin McCain; ments to change their discriminatory overreaching WOTUS regulations. and Joseph McNeil—were students policies. On July 26, 1960, the Wool- In addition to taking away States’ from North Carolina A&T College, now worth’s lunch counter was finally inte- authority to manage water resources, known as North Carolina A&T State grated. Today, the former Woolworth’s the 2015 WOTUS rule expanded the University. I might add that A&T now houses the International Civil Clean Water Act far beyond the law’s State University is now the largest Rights Center and Museum, which fea- historical limits of navigable waters HBCU in the country. tures a restored version of the lunch and the long-held intent of Congress. Mr. Speaker, I would also mention counter where the Greensboro Four Instead of providing much-needed clar- that Congresswoman ALMA ADAMS is a sat. Part of the original counter is on ity to the Clean Water Act, WOTUS graduate of A&T State University and display at the Smithsonian National created even more confusion. served as a college professor across the Museum of American History here in Thankfully, the negative impact of street at Bennett College for more than Washington. WOTUS was brought to an end when 40 years. On Saturday of this week, February the Trump administration repealed it The Greensboro Four students were 1, the museum will commemorate the this past fall. -

A&T Four Box 0002

Inventory of the A&T Four Collection, Box 002 Contact Information Archives and Special Collections F.D. Bluford Library North Carolina A&T State University Greensboro, NC 27411 Telephone: 336-285-4176 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ncat.edu/resources/archives Descriptive Summary Repository F. D. Bluford Library Archives and Special Collections Creator Franklin McCain Ezell Blair, Jr. (Jibreel Khazan) David Richmond, Sr. Joseph Mc Neil Title “A&T Four” Box #2 Language of Materials English Extent 1 archival boxes, 121 items, 1.75 linear feet Abstract The Collection consists Events programs and newspaper articles and editorials commemorating the 1960 sit-ins over the years from 1970s to 2000s. The articles cover how A&T, Greensboro and the nation honor the Four and the sit-in movement and its place in history. They also put it in context of racial relations contemporary with their publication. Administrative Information Restrictions to Access No Restrictions Acquisitions Information Please consult Archives Staff for additional information. Processing Information Processed by James R. Jarrell, April 2005; Edward Lee Love, Fall 2016. Preferred Citation [Identification of Item], in the A&T Four Box 2, Archives and Special Collections, Bluford Library, North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, Greensboro, NC. Copyright Notice North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College owns copyright to this collection. Individuals obtaining materials from Bluford Library are responsible for using the works in conformance with United State Copyright Law as well as any restriction accompanying the materials. Biographical Note On February 1, 1960, NC A&T SU freshmen Franklin McCain, David Richmond, Joseph McNeil, and Ezell Blair (Jibreel Khazan) sat down at the whites only lunch counter at the F.W. -

FEBRUARY ONE Lesson Plan Pbs.Org/Independentlens/Februaryone the Greensboro Sit-Ins: a Continuing Tradition of Nonviolent Protest

FEBRUARY ONE Lesson Plan pbs.org/independentlens/februaryone The Greensboro Sit-Ins: A Continuing Tradition of Nonviolent Protest Grade Levels: 8-12 Estimated time: Four class periods (three if you choose to assign the Assessment activity for homework) Introduction: The Greensboro Four were adamant that their lunch counter protest be nonviolent. They based this philosophy on the teachings of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Mahatma Gandhi, who received much of their guidance from the teachings of Jesus as outlined in the Sermon on the Mount in the Bible’s New Testament. The success of their protest has been attributed in large part to its adherence to this nonviolent approach. Students will learn more about the philosophy of nonviolence by reading a sermon given by Dr. King, two passages about Gandhi, and some verses from the Sermon on the Mount. They will view the FEBRUARY ONE program with the goal of learning about the nonviolent approach and seeing how this technique succeeded. They will also read the letter that the Greensboro Four wrote to people who were considering participating in the sit-ins. They will conclude the lesson by imagining that they’re organizing a protest after the sit-ins and writing letters that explain the nonviolent method to people who are considering joining the protest. It would be ideal if students have a general understanding of the Civil Rights Movement before doing this lesson. Lesson Objectives: Students will: • Review some basic information about the Civil Rights Movement. • Watch an excerpt from FEBRUARY ONE which provides a historical background to the Greensboro sit-ins and introduces the protest, and consider what they might do in a situation similar in which the Greensboro students found themselves. -

1960: the Greensboro Sit

1960: The Greensboro Sit Ins When Four students sat down at a lunch counter in Greensboro, N.C., over 50 years ago, they helped re- ignite the Civil Rights Movement By Suzanne Bilyeu It was shortly after four in the afternoon when four college freshmen entered the Woolworth's store in downtown Greensboro, North Carolina. They purchased a few small items—school supplies, toothpaste—and were careful to keep their receipts. Then they sat down at the store's lunch counter and ordered coffee. "I'm sorry," said the waitress. "We don't serve Negroes here." "I beg to differ," said one of the students. He pointed out that the store had just served them—and accepted their money—at a counter just a few feet away. They had the receipts to prove it. A black woman working at the lunch counter scolded the students for trying to stir up trouble, and the store manager asked them to leave. But the four young men sat quietly at the lunch counter until the store closed at 5:30. Ezell Blair Jr., Franklin McCain, Joseph McNeil, and David Richmond, now known as the "Greensboro Four," were all students at North Carolina A&T (Agricultural and Technical) College, a black college in Greensboro. They were teenagers, barely out of high school. But on that Monday afternoon, Feb. 1, 1960, they started a movement that changed America. A Decade of Protest The Greensboro sit-in 50 years ago, and those that followed, ignited a decade of civil rights protests in the U.S. It was a departure from the approach of the N.A.A.C.P. -

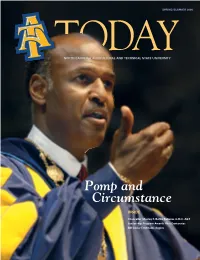

Pomp and Circumstance

SPRING/SUMMER 2008 TODAY NORTH CAROLINA AGRICULTURAL AND TECHNICAL STATE UNIVERSITY Pomp and Circumstance INSIDE Chancellor Stanley F. Battle Believes in N.C. A&T Leadership Program Awards First Doctorates Bill Cosby Entertains Aggies TONorth Carolina AgriculturalD and Technical AState UniversityY Spring/Summer 2008 DEPARTMENTS ARTICLES 2) Inside Aggieland 9) Distinguished Nanoscientist to Lead Joint School 5) Campus Briefs 12) Leadership Program Awards First Doctorates 8) Research 22) Perseverance Sustains Aggie Club 23) Aggie Sports 26) Aggies on the Move FEATURE ARTICLES 29) In Memoriam 14) A Twinspirational Moment 32) Mixed Bag A&T’s top senior and twin brother surprise mom at commencement 18) I Believe in North Carolina A&T Chancellor Stanley Fred Battle’s Installation Address 30) “FUNraising” North Carolina Agricultural and Technical Alumni use non-traditional methods to State University is a learner-centered community that develops and preserves raise funds for N.C. A&T intellectual capital through interdisciplinary PAGE 18 learning, discovery, engagement, and operational excellence. PAGE 12 PAGE 14 PAGE 16 On the Cover: A&T TODAY Editor Printing Executive Cabinet Alumni Association Board of Directors Chancellor Stanley North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University Sandra M. Brown P.N. Thompson/Henry Wurst, Inc. Chancellor - Stanley F. Battle President - Pamela L. Johnson ’91 Fred Battle Spring/Summer 2008 Provost/Vice Chancellor, Academic Affairs - Alton Thompson (Interim) First Vice President - Marvin L. Walton ’91 Editorial Assistants Board of Trustees Vice Chancellor, Business and Finance - Robert Pompey Jr. ’87 Second Vice President - “Chuck” Burch Jr. ’82 Velma R. Speight-Buford ’53, Chair A&T TODAY is published quarterly by Samantha V. -

Freedom on the Menu: the Greensboro Sit-Ins Lesson

WTTM 2016 Grade 2 Freedom on the Menu: The Greensboro Sit-Ins Lesson Summary Students will explore how segregation affected every day and ways to respond to injustice and discrimination. This will lead into discussion of civil disobedience, non-violent demonstrations, and the power of the written word. After engaging students in a discussion of segregation, the teacher reads Freedom on the Menu to second graders. The teacher then leads students in discussion of major issues raised by the text. Students brainstorm slogans and design signs that they would have carried on the picket lines. Introduction On February 1, 1960, four African-American students of North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University sat at a white-only lunch counter inside a Greensboro, North Carolina Woolworth’s store. While sit-ins had been held elsewhere in the United States, the Greensboro sit-in catalyzed a wave of nonviolent protest against private-sector segregation. Materials Photo handout Freedom on the Menu: The Greensboro Sit-Ins by Carole Boston Weatherford Markers and paper Procedures 1. Distribute photo handout to students. Define segregation for the students and ask them to find examples of segregation in the pictures. Explain that segregation was part of a larger set of laws called Jim Crow laws. Cite several laws that affected children: separate rooms or sections of restaurants and libraries, separate schools, theaters, lunch counters and public parks, and separate ticket offices and entrances to circuses and other shows. One North Carolina law stated, “Books shall not be interchangeable the white and colored school, but shall continue to be used by the race first using them.” 2. -

February One

February One Documentary Film Study Guide By Rebecca Cerese & Diane Wright Available online at www.newsreel.org Film Synopsis Greensboro, North Carolina, was a fairly typical Southern city in the middle of the 20th Century. The city was certainly segregated, but city officials prided themselves on handling race relations with more civility than many other Southern cities. Ezell Blair, Jr. (who later changed his name to Jibreel Khazan) was the son of an early member of the NAACP, who introduced him to the idea of activism at an early age. Ezell attended segregated Dudley High School, where he befriended Franklin McCain. Franklin, raised in the more racially open city of Washington, DC, was angered by the segregation he encountered in Greensboro. Ezell and Franklin became fast friends with David Richmond, the most popular student at Dudley High. In 1958, Ezell and David heard Martin Luther King, Jr., speak at Bennett College in Greensboro. At the same time, the rapid spread of television was bringing images of oppression and conflict from around the world into their living rooms. Ezell was inspired by the non-violent movement for independence led by Mahatma Gandhi and chilled by the brutal murder of Emmett Till. In the fall of 1959, Ezell, Franklin, and David enrolled in Greensboro’s all-black college, North Carolina A&T State University. Ezell’s roommate was Joseph McNeil, an idealistic young man from New York City. Ezell, Franklin, David, and Joseph became a close-knit group and got together for nightly bull sessions in their dorm rooms. During this time they began to consider challenging the institution of segregation. -

Sitting Down to Stand up for Democracy

Sitting Down To Stand Up For Democracy Overview Students will evaluate the actions of various citizens during the Civil Rights Movement and how their actions brought about changes for society (then and now) through the examination of poetry, biographies, speeches, photographs, historical events, and civil rights philosophies. Grade 8 North Carolina Essential Standards for 8th Grade • 8.H.1: Apply historical thinking to understand the creation and development of North Carolina and the United States. • 8.H.2.1: Explain the impact of economic, political, social, and military conflicts (e.g. war, slavery, states’ rights and citizenship and immigration policies) on the development of North Carolina and the United States • 8.H.2.2: Summarize how leadership and citizen actions influenced the outcome of key conflicts in North Carolina and the United States. • 8.H.3.3: Explain how individuals and groups have influenced economic, political and social change in North Carolina and the United States. • 8.C&G.1.4: Analyze access to democratic rights and freedoms among various groups in North Carolina and the United States • 8.C&G.2.1: Evaluate the effectiveness of various approaches used to effect change in North Carolina and the United States • 8.C&G.2.2: Analyze issues pursued through active citizen campaigns for change • 8.C&G.2.3: Explain the impact of human and civil rights issues throughout North Carolina and United States history • 8.C.1.3: Summarize the contributions of particular groups to the development of North Carolina and the United States Essential Questions • In what ways were African Americans deprived of equality during the Jim Crow Era? • In what ways did citizens and engaged community members work to bring about change during the Civil Rights Movement? • Evaluate the effectiveness and/or ineffectiveness of legislation in regards to eQual rights. -

International Civil Rights Center & Museum

★ Celebrate Greensboro art. Culture. Entertainment. By Tara TiTcomBe A movement that inspired the nation The International Civil Rights Center & Museum must-see vital piece of history stands and the following with more in the center of downtown Greensboro, than 300. By the end of that March, similar protests were welcoming and educating all who visit. taking place in more than The International Civil Rights Center 55 cities and 13 states. The & Museum tells the story of the non- non-violent sit-in movement was born, and the nation would tre violent civil rights movement that be- never be the same. A the gan 51 years ago in its very location. Today the International A rolin Civil Rights Center & A Museum, housed in the former the c M F AOn February 1, 1960, four African-American Woolworth store in downtown Greensboro, freshmen from Greensboro’s N.C. A&T State celebrates that moment in history and University sat down at the F.W. Woolworth remains devoted to the global struggle for enter & Museu c store’s “whites only” civil and human rights. ights r Visit, ExplorE , Learn lunch counter and The two-floor, 43,000-square-foot ivil c For more information on Greensboro’s ordered coffee. They museum opened on February 1, 2010 — l A International Civil Rights Center & were denied service, commemorating the 50th anniversary of the tion A Museum, stop by 134 South Elm St., call nd (right) Andy Ferrell/courtesy o 336 . 274.9199 or 800.748 .7 116, or check ignored, then asked to sit-ins.