New Armed Groups in Colombia: the Emergence of the Bacrim in the 21St Century a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Informe 2013 Bacrim

Las BACRIM despue s de 2013: ¿prono stico reservado? BERNARDO PÉREZ SALAZAR CARLOS MONTOYA CELY A mediados de 2012, el ministro de defensa, Juan Carlos Pinzón, dio un parte de tranquilidad frente a las bandas criminales –bacrim–, señalando que en 934 municipios del país “no hay presencia de bandas criminales”.1 No aclaró el alcance de la expresión “no hay presencia” ni la definición de “banda criminal”. Tampoco refirió cómo llegó a la mentada cifra de municipios. En todo caso la declaración contrastó visiblemente con el parte que a principios del 2011 habían entregado las autoridades de la Policía Nacional, con el general Oscar Naranjo a la cabeza, al indicar que las vendettas y los ajustes de cuentas entre narcos representarían el 47% de los 15.400 homicidios registrados en 2010. Dadas las violentas disputas territoriales que se registraban en aquel entonces por el control del “microtráfico” en sectores urbanos de Medellín entre alias “Sebastián” y “Valenciano”, así como por rutas de narcotráfico en Córdoba entre “Paisas” (aliados a los Rastrojos) y “Aguilas Negras“ (aliados de los Urabeños), no es de extrañar que una nota informativa cubriendo la noticia se hubiese titulado: “Las bacrim cometen la mitad de los asesinatos en Colombia”.2 Declaraciones sobre el tema del entonces ministro del Interior, Germán Vargas Lleras, entregadas también en enero de 2011, no fueron menos inquietantes, y se resumieron en el titular “Las bacrim ya actúan en 24 departamentos colombianos”, lo que propició que algunos analistas refirieran la presencia de -

PRISM Vol 5, No.1

PRISM VOL. 5, NO. 1 2014 A JOURNAL OF THE CENTER FOR COMPLEX OPERATIONS PRISM About VOL. 5, NO. 1 2014 PRISM is published by the Center for Complex Operations. PRISM is a security studies journal chartered to inform members of U.S. Federal agencies, allies, and other partners on complex EDITOR and integrated national security operations; reconstruction and state-building; relevant policy Michael Miklaucic and strategy; lessons learned; and developments in training and education to transform America’s security and development EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Ross Clark Ben Graves Caliegh Hernandez Communications Daniel Moore Constructive comments and contributions are important to us. Direct communications to: COPY EDITORS Dale Erickson Editor, PRISM Rebecca Harper 260 Fifth Avenue (Building 64, Room 3605) Christoff Luehrs Fort Lesley J. McNair Sara Thannhauser Washington, DC 20319 Nathan White Telephone: (202) 685-3442 DESIGN DIRecTOR FAX: Carib Mendez (202) 685-3581 Email: [email protected] ADVISORY BOARD Dr. Gordon Adams Dr. Pauline H. Baker Ambassador Rick Barton Contributions Professor Alain Bauer PRISM welcomes submission of scholarly, independent research from security policymakers Dr. Joseph J. Collins (ex officio) and shapers, security analysts, academic specialists, and civilians from the United States and Ambassador James F. Dobbins abroad. Submit articles for consideration to the address above or by email to [email protected] Ambassador John E. Herbst (ex officio) with “Attention Submissions Editor” in the subject line. Dr. David Kilcullen Ambassador Jacques Paul Klein Dr. Roger B. Myerson This is the authoritative, official U.S. Department of Defense edition of PRISM. Dr. Moisés Naím Any copyrighted portions of this journal may not be reproduced or extracted MG William L. -

Fuerzas Militares

Editores Hubert Gehring El presente libro reexiona sobre los nuevos roles domésticos e internacionales de las Fuerzas Militares en la construcción de paz y Eduardo Pastrana Buelvas el fortalecimiento del Estado, luego de que el Gobierno colombiano, en cabeza del expresidente Juan Manuel Santos, negoció y acordó el n del conicto armado interno con la mayor y más antigua guerrilla: las Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC-EP). No obstante, el posacuerdo ha implicado para las FF.MM. la continuidad de misiones no convencionales, como la lucha contra el ELN (Ejército de Liberación Nacional), las disidencias de las FARC-EP, las bandas criminales ligadas al narcotráco, la minería ilegal y la depredación del medio ambiente, así como también tareas Fuerzas Militares de apoyo al desarrollo estructural e institucional del país. Sin embargo, el posacuerdo plantea también un cambio para que de Colombia: se abran escenarios en misiones convencionales, como el control de las fronteras de manera conjunta con otros países de la región La Fundación Konrad Adenauer (KAS) es una fundación para combatir actividades criminales transfronterizas y confrontar nuevos roles y desafíos político alemana con orientación democráta cristiana las nuevas amenazas que enfrenta el sistema internacional. Así Autores allegada a la Unión Demócrata Cristiana (CDU). mismo, las FF.MM. advierten la necesidad de concebir sus roles nacionales e internacionales Carlos Enrique Álvarez Calderón institucionales en relación con la importancia de armonizar su Mario Arroyave Quintero Para la Fundación Konrad Adenauer, la principal meta de transformación con los procesos de ampliación democrática, Javier Alberto Ayala Amaya nuestro trabajo es el fortalecimiento de la democracia en emergentes en el mismo posacuerdo, al igual que adquirir Jaime Baeza Freer todas sus dimensiones. -

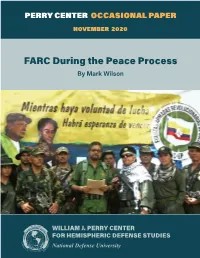

FARC During the Peace Process by Mark Wilson

PERRY CENTER OCCASIONAL PAPER NOVEMBER 2020 FARC During the Peace Process By Mark Wilson WILLIAM J. PERRY CENTER FOR HEMISPHERIC DEFENSE STUDIES National Defense University Cover photo caption: FARC leaders Iván Márquez (center) along with Jesús Santrich (wearing sunglasses) announce in August 2019 that they are abandoning the 2016 Peace Accords with the Colombian government and taking up arms again with other dissident factions. Photo credit: Dialogo Magazine, YouTube, and AFP. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and are not an official policy nor position of the National Defense University, the Department of Defense nor the U.S. Government. About the author: Mark is a postgraduate candidate in the MSc Conflict Studies program at the London School of Economics. He is a former William J. Perry Center intern, and the current editor of the London Conflict Review. His research interests include illicit networks as well as insurgent conflict in Colombia specifically and South America more broadly. Editor-in-Chief: Pat Paterson Layout Design: Viviana Edwards FARC During the Peace Process By Mark Wilson WILLIAM J. PERRY CENTER FOR HEMISPHERIC DEFENSE STUDIES PERRY CENTER OCCASIONAL PAPER NOVEMBER 2020 FARC During the Peace Process By Mark Wilson Introduction The 2016 Colombian Peace Deal marked the end of FARC’s formal military campaign. As a part of the demobilization process, 13,000 former militants surrendered their arms and returned to civilian life either in reintegration camps or among the general public.1 The organization’s leadership were granted immunity from extradition for their conduct during the internal armed conflict and some took the five Senate seats and five House of Representatives seats guaranteed by the peace deal.2 As an organiza- tion, FARC announced its transformation into a political party, the Fuerza Alternativa Revolucionaria del Común (FARC). -

The Changing Face of Colombian Organized Crime

PERSPECTIVAS 9/2014 The Changing Face of Colombian Organized Crime Jeremy McDermott ■ Colombian organized crime, that once ran, unchallenged, the world’s co- caine trade, today appears to be little more than a supplier to the Mexican cartels. Yet in the last ten years Colombian organized crime has undergone a profound metamorphosis. There are profound differences between the Medellin and Cali cartels and today’s BACRIM. ■ The diminishing returns in moving cocaine to the US and the Mexican domi- nation of this market have led to a rapid adaptation by Colombian groups that have diversified their criminal portfolios to make up the shortfall in cocaine earnings, and are exploiting new markets and diversifying routes to non-US destinations. The development of domestic consumption of co- caine and its derivatives in some Latin American countries has prompted Colombian organized crime to establish permanent presence and structures abroad. ■ This changes in the dynamics of organized crime in Colombia also changed the structure of the groups involved in it. Today the fundamental unit of the criminal networks that form the BACRIM is the “oficina de cobro”, usually a financially self-sufficient node, part of a network that functions like a franchise. In this new scenario, cooperation and negotiation are preferred to violence, which is bad for business. ■ Colombian organized crime has proven itself not only resilient but extremely quick to adapt to changing conditions. The likelihood is that Colombian organized crime will continue the diversification -

Nuevos Escenarios De Conflicto Armado Y Violencia

NORORIENTE Y MAGDALENA MEDIO, LLANOS ORIENTALES, SUROCCIDENTE Y BOGOTÁ DC NUEVOS ESCENARIOS DE CONFLICTO ARMADO Y VIOLENCIA Panorama posacuerdos con AUC Nororiente y Magdalena Medio, Llanos Orientales, Félix Tomás Bata Jiménez Suroccidente y Bogotá DC Blanca Berta Rodríguez Peña NUEVOS ESCENARIOS DE CONFLICTO ARMADO Y VIOLENCIA Representantes de organizaciones de víctimas Panorama posacuerdos con AUC CENTRO NACIONAL DE MEMORIA HISTÓRICA Director General Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica Gonzalo Sánchez Gómez Gonzalo Sánchez Gómez Director General Coordinador de la investigación y edición Asesores de Dirección Álvaro Villarraga Sarmiento María Emma Wills Obregón, Patricia Linares Prieto, Paula Andrea Ila, Andrés Fernando Suárez, Luz Amanda Granados Urrea, Doris Yolanda Asistente de Coordinación Ramos Vega, César Augusto Rincón Vicentes Sandra Marcela Flórez Directores Técnicos Investigadores e Investigadoras Alberto Santos Peñuela, Lukas Rodríguez Lizcano, Luisa Fernanda Álvaro Villarraga Sarmiento Hernández Mercado y Juanita Esguerra Rezk Dirección Acuerdos de la Verdad Comité de Lectores /Lectoras del CNMH Martha Angélica Barrantes Reyes Nororiente: Vladimir Caraballo, investigador CNMH-DAV Dirección para la Construcción de la Memoria Histórica Llanos Orientales: Bernardo Pérez, investigador, Fundación Paz y Reconciliación Ana Margoth Guerrero de Otero Suroccidente: Adolfo Atehortúa. Doctor en Sociología EHESS París, Dirección de Archivos de Derechos Humanos Francia. Profesor UPN Bogotá DC: Oscar David Andrade Becerra. Asesor Cualitativo -

Diapositiva 1

Latina Finance & Co Corporate Finance Advisory in Latin America Latin America 2009 Political, Economical and Financial snapshot January 2010 Latina Finance & Co www.latinafinance.net Table of contents 1. Introduction 2. Latin America political 2009 3. Latin America economical 2009 4. Latin America financial 2009 5. Latam – Europe business 2009 6. Outlook 2010 7. Contact 8. Disclaimer Latina Finance & Co 2 1 . Introduction We are very happy to provide you with a quick overview of what has been the year 2009 in Latin America. It is not an extensive review but much more a snapshot which should hopefully provide you with a helicopter view of what has been a very interesting year. We have now entered 2010 and the prospect for this year is encouraging with continuous political stability in the key countries of the region and confirmation of an increasing democratic environment. Brazil is taking the lead of the region’s economic recovery with Peru, Chile and Colombia following the path. Mexico should follow the footsteps of the US progressive recovery. Argentina still needs to fix its debt restructuring issue which it will hopefully achieve in 2010. After a great 4Q rally, financial markets seem to be pursuing a positive trend in early 2010. Equity and capital markets should keep a strong momentum while the bank market might reopen as banks will have re-adjusted their capital ratios . Given the strong demand for infrastructure financing, project financing should continue to recover with the support of multi and bilateral organizations such as BNDES, IADB, IFC and EIB. One can also see renewed interest from large US private equity funds which could tempt European PEs to enter the region. -

Targeting Civilians in Colombia's Internal Armed

‘ L E A V E U S I N P E A C E ’ T LEAVE US IN A ‘ R G E T I N G C I V I L I A N S PEA CE’ I N C O TARG ETING CIVILIANS L O M B I A IN COL OM BIA S INTERNAL ’ S ’ I N T E R ARMED CONFL IC T N A L A R M E D C O N F L I C ‘LEAVE US IN PEACE’ T TARGETING CIVILIANS IN COLOMBIA ’S INTERNAL ARMED CONFLICT “Leave us in peace!” – Targeting civilians in Colombia’s internal armed conflict describes how the lives of millions of Colombians continue to be devastated by a conflict which has now lasted for more than 40 years. It also shows that the government’s claim that the country is marching resolutely towards peace does not reflect the reality of continued A M violence for many Colombians. N E S T Y At the heart of this report are the stories of Indigenous communities I N T decimated by the conflict, of Afro-descendant families expelled from E R their homes, of women raped and of children blown apart by landmines. N A The report also bears witness to the determination and resilience of T I O communities defending their right not to be drawn into the conflict. N A L A blueprint for finding a lasting solution to the crisis in Colombia was put forward by the UN more than 10 years ago. However, the UN’s recommendations have persistently been ignored both by successive Colombian governments and by guerrilla groups. -

PREFACE the Influence of Organised Crime in the Balkan Area, As Is Well

PREFACE The influence of organised crime in the Balkan area, as is well known, has reached levels that have required a considerable acceleration in efforts to combat this phenomenon. Albania is involved in many initiatives set up by the international community, which are matched by efforts at national level. In 2005, the Democratic Party achieved a decisive victory in the political elections with the support of its allies, making a commitment to reduce crime and corruption in the country. This victory, and more importantly the ordered transition of power which followed it, has been regarded at international level as an important step forward towards the confirmation of democracy. Despite the active presence of organised criminal groups over the territorial area and the influence exercised by them in the country's already critical social and economic situation, Albania, recognising the need to bring its legislation up to date and to strengthen the institutions responsible for fighting crime, has moved with determination in the direction of reform. With regard to bringing the legislation into line with international standards, we should remember that in 2002 Albania ratified the United Nations Convention against Trans National Organised Crime (UNTOC) and the relative additional protocols preventing the smuggling of migrants and trafficking of human beings. In February 2008 it also ratified the third and final protocol on arms trafficking. Since 1995, Albania has been a member country of the Council of Europe; in 2001 it became a member of the Group of States Against Corruption (GRECO) and in 2006 it also ratified the United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC). -

COLOMBIA Executive Summary the Constitution and Other Laws And

COLOMBIA Executive Summary The constitution and other laws and policies protect religious freedom and, in practice, the government generally respected religious freedom. The government did not demonstrate a trend toward either improvement or deterioration in respect for and protection of the right to religious freedom. Illegal armed groups, including the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), killed, kidnapped, and extorted religious leaders and practitioners, inhibiting free religious expression in some areas. The National Liberation Army (ELN) continued to threaten members of religious organizations. Terrorist organizations generally targeted religious leaders and practitioners for political rather than religious reasons. Organized crime groups that included some former members of paramilitary groups also targeted representatives and members of religious organizations. There were some reports of societal abuses or discrimination based on religious affiliation, belief, or practice. U.S. embassy representatives met with representatives of a wide range of religious groups and the government, and supported preservation of sites of religious and cultural importance. Section I. Religious Demography The government does not keep statistics on religious affiliation, and estimates from religious leaders varied. A majority of the population is Roman Catholic. According to the Colombian Evangelical Council (CEDECOL), approximately 15 percent of the population is Protestant, whereas the Catholic Bishops’ Conference estimates that 90 percent -

Uruguay Latin America´S #1 Business Gateway

2 3 Business Platforms for Life Sciences Companies in Uruguay1 Both pharmaceutical and medical device companies, combine different business platforms, taking advantage of Uruguay´s value proposition - stability, no restrictions on foreign exchange and repatriation of profits, outstanding tax exemptions, talent availability and quality of life, cold chain and logistics for access to Brazil and countries in the region minimizing time and costs. 1 R&D: Research & Development RDC: Regional Distribution Centers HQ-SSC: Regional Head Quarters or Shared Services Centers 4 Life Science Success Stories Roche has a Regional Supply Center in Uruguay which coordinates all logistic activities in Latin America. Also, the Center manages goods supply from the production centers to all its affiliates in the region. The main activities of the Regional Supply Center include: orders management, billing, and customer service. Thus, the Center has three different departments: Intercompany Operations, Supply Chain, and Transport. Each department ensures an alignment with regional interests and requirements. Shimadzu Corporation manufactures analytical tools for precision and measurement, medical imaging systems, aircraft equipment and other industrial equipment. Shimadzu Latinoamérica S.A, works as a Regional Distribution Logistics center throughout Latin America for medical equipment, and analytical equipment (precision balances, and laboratory equipment). The company has business offices, a warehouse and their Regional Headquarters in Uruguay, which they moved from Brazil in 2013. HQ, SSC, Trading & Procurement Merck settled in Uruguay in 1996. The company develops logistic and business services lead by regional and global positions. The operation has grown steadily, following Merck’s growth in Latin America, and currently 80 employees work in both platforms. -

Xi Informe Sobre Presencia De Grupos Narcoparamilitares 2014

NARCOPARAMILITARISMO Y RETOS PARA LOS ACUERDOS DE PAZ XI INFORME SOBRE PRESENCIA DE GRUPOS NARCOPARAMILITARES 2014 36 NARCOPARAMILITARISMO Y RETOS PARA LOS ACUERDOS DE PAZ V. Dirección y gestión del Plan de Urgencia y de los programas en las zonas y NARCOPARAMILITARISMO Y RETOS subzonas escogidas PARA LOS ACUERDOS DE PAZ 1. La Dirección del Plan de Urgencia estará a cargo de la instancia acordada por la Mesa de Paz de La Habana para coordinar el conjunto de la implementación de los acuerdos. Resumen de caracterización 2. Para la puesta en marcha inmediata de los componentes del Plan el gobierno creará una Unidad Interinstitucional, con oficina en cada subzona definida. Una comisión especial acordada en la Mesa de Paz de La Habana colaborará desde ahora con la Unidad Interinstitucional y designará personas Unidad de análisis de INDEPAZ que sean indispensables para la coordinación e implementación del Plan en los territorios. En los acuerdos de implementación se definirán la composición permanente de la Comisión Especial mixta INDEPAZ ha hecho un seguimiento sobre la presencia de grupos paramilitares o narcoparamilitares y las formas de la cooperación posterior a la firma delAcuerdo Final de terminación del conflicto y en Colombia desde el año 2006. Hasta la fecha se han publicado ocho Informes con registros anuales construcción de una paz estable y duradera. y uno con avances semestrales. El objetivo de la investigación ha sido ofrecer a las organizaciones 3. En las instancias de dirección y de gestión en las zonas se incluirán delegados de las organizaciones, sociales y defensoras de derechos humanos mapas sobre la evolución del paramilitarismo después asociaciones y empresas que sean representativas y pertinentes para el Plan de Urgencia y las de las desmovilizaciones en 2005 y 2006 y evaluar su incidencia en el conflicto armado y en el medidas sociales y económicas a desarrollar.