The Topic of Terrorism on Yahoo! Answers : Questions, Answers and Users’ Anonymity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recommending Best Answer in a Collaborative Question Answering System

RECOMMENDING BEST ANSWER IN A COLLABORATIVE QUESTION ANSWERING SYSTEM Mrs Lin Chen Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Information Technology (Research) School of Information Technology Faculty of Science & Technology Queensland University of Technology 2009 Recommending Best Answer in a Collaborative Question Answering System Page i Keywords Authority, Collaborative Social Network, Content Analysis, Link Analysis, Natural Language Processing, Non-Content Analysis, Online Question Answering Portal, Prestige, Question Answering System, Recommending Best Answer, Social Network Analysis, Yahoo! Answers. © 2009 Lin Chen Page i Recommending Best Answer in a Collaborative Question Answering System Page ii © 2009 Lin Chen Page ii Recommending Best Answer in a Collaborative Question Answering System Page iii Abstract The World Wide Web has become a medium for people to share information. People use Web- based collaborative tools such as question answering (QA) portals, blogs/forums, email and instant messaging to acquire information and to form online-based communities. In an online QA portal, a user asks a question and other users can provide answers based on their knowledge, with the question usually being answered by many users. It can become overwhelming and/or time/resource consuming for a user to read all of the answers provided for a given question. Thus, there exists a need for a mechanism to rank the provided answers so users can focus on only reading good quality answers. The majority of online QA systems use user feedback to rank users’ answers and the user who asked the question can decide on the best answer. Other users who didn’t participate in answering the question can also vote to determine the best answer. -

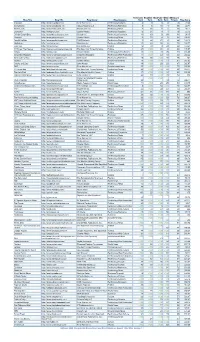

Blog Title Blog URL Blog Owner Blog Category Technorati Rank

Technorati Bloglines BlogPulse Wikio SEOmoz’s Blog Title Blog URL Blog Owner Blog Category Rank Rank Rank Rank Trifecta Blog Score Engadget http://www.engadget.com Time Warner Inc. Technology/Gadgets 4 3 6 2 78 19.23 Boing Boing http://www.boingboing.net Happy Mutants LLC Technology/Marketing 5 6 15 4 89 33.71 TechCrunch http://www.techcrunch.com TechCrunch Inc. Technology/News 2 27 2 1 76 42.11 Lifehacker http://lifehacker.com Gawker Media Technology/Gadgets 6 21 9 7 78 55.13 Official Google Blog http://googleblog.blogspot.com Google Inc. Technology/Corporate 14 10 3 38 94 69.15 Gizmodo http://www.gizmodo.com/ Gawker Media Technology/News 3 79 4 3 65 136.92 ReadWriteWeb http://www.readwriteweb.com RWW Network Technology/Marketing 9 56 21 5 64 142.19 Mashable http://mashable.com Mashable Inc. Technology/Marketing 10 65 36 6 73 160.27 Daily Kos http://dailykos.com/ Kos Media, LLC Politics 12 59 8 24 63 163.49 NYTimes: The Caucus http://thecaucus.blogs.nytimes.com The New York Times Company Politics 27 >100 31 8 93 179.57 Kotaku http://kotaku.com Gawker Media Technology/Video Games 19 >100 19 28 77 216.88 Smashing Magazine http://www.smashingmagazine.com Smashing Magazine Technology/Web Production 11 >100 40 18 60 283.33 Seth Godin's Blog http://sethgodin.typepad.com Seth Godin Technology/Marketing 15 68 >100 29 75 284 Gawker http://www.gawker.com/ Gawker Media Entertainment News 16 >100 >100 15 81 287.65 Crooks and Liars http://www.crooksandliars.com John Amato Politics 49 >100 33 22 67 305.97 TMZ http://www.tmz.com Time Warner Inc. -

Location-Based Services: Industrial and Business Analysis Group 6 Table of Contents

Location-based Services Industrial and Business Analysis Group 6 Huanhuan WANG Bo WANG Xinwei YANG Han LIU Location-based Services: Industrial and Business Analysis Group 6 Table of Contents I. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................. 2 II. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................ 3 III. Analysis ................................................................................................................................................................ 3 IV. Evaluation Model .................................................................................................................................................. 4 V. Model Implementation ........................................................................................................................................... 6 VI. Evaluation & Impact ........................................................................................................................................... 12 VII. Conclusion ........................................................................................................................................................ 16 1 Location-based Services: Industrial and Business Analysis Group 6 I. Executive Summary The objective of the report is to analyze location-based services (LBS) from the industrial -

Sustaining Software Innovation from the Client to the Web Working Paper

Principles that Matter: Sustaining Software Innovation from the Client to the Web Marco Iansiti Working Paper 09-142 Copyright © 2009 by Marco Iansiti Working papers are in draft form. This working paper is distributed for purposes of comment and discussion only. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies of working papers are available from the author. Principles that Matter: Sustaining Software Innovation 1 from the Client to the Web Marco Iansiti David Sarnoff Professor of Business Administration Director of Research Harvard Business School Boston, MA 02163 June 15, 2009 1 The early work for this paper was based on a project funded by Microsoft Corporation. The author has consulted for a variety of companies in the information technology sector. The author would like to acknowledge Greg Richards and Robert Bock from Keystone Strategy LLC for invaluable suggestions. 1. Overview The information technology industry forms an ecosystem that consists of thousands of companies producing a vast array of interconnected products and services for consumers and businesses. This ecosystem was valued at more than $3 Trillion in 2008.2 More so than in any other industry, unique opportunities for new technology products and services stem from the ability of IT businesses to build new offerings in combination with existing technologies. This creates an unusual degree of interdependence among information technology products and services and, as a result, unique opportunities exist to encourage competition and innovation. In the growing ecosystem of companies that provide software services delivered via the internet - or “cloud computing” - the opportunities and risks are compounded by a significant increase in interdependence between products and services. -

2019-09-23-UNGA-Release 0.Pdf

News Release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media contact: September 23, 2019 Bernadette Brijlall [email protected] Alex Martinetti [email protected] Ground-Breaking Immersive Installation Brings to Life Urgency of Climate Action What you need to know: 2019 Climate Action Summit kicked off with an immersive look at devasting impacts of climate change, produced by RYOT a Verizon Media company. Verizon to focus its support of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), emphasizing SDG 4: Quality Education and SDG 13: Climate Action, through social responsibility programs such as Verizon Innovative Learning and the company's sustainability efforts. New York, New York (September 23, 2019) – As world leaders and diplomats convene for the 74th United Nations General Assembly (UNGA), Verizon continues to focus on responsible business and the power of cutting-edge technology to deliver compelling story-telling that reinforces the need for urgent climate action. During UNGA, Verizon will focus on its support of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), emphasizing SDG 4: Quality Education and SDG 13: Climate Action, through social responsibility programs such as Verizon Innovative Learning and the company's sustainability efforts. Verizon has also joined the UN Global Compact, as part of a long-term pledge to a principles-based approach to corporate sustainability that upholds a commitment to people and the planet. As part of UNGA, the 2019 Climate Action Summit kicked off with an immersive look at the devastating impacts climate change is having right now, as well as the vast opportunities ahead as the world moves from the grey to the green economy, with technological innovation playing a key role. -

Why Google Dominates Advertising Markets Competition Policy Should Lean on the Principles of Financial Market Regulation

Why Google Dominates Advertising Markets Competition Policy Should Lean on the Principles of Financial Market Regulation Dina Srinivasan* * Since leaving the industry, and authoring The Antitrust Case Against Face- book, I continue to research and write about the high-tech industry and competition, now as a fellow with Yale University’s antitrust initiative, the Thurman Arnold Pro- ject. Separately, I have advised and consulted on antitrust matters, including for news publishers whose interests are in conflict with Google’s. This Article is not squarely about antitrust, though it is about Google’s conduct in advertising markets, and the idea for writing a piece like this first germinated in 2014. At that time, Wall Street was up in arms about a book called FLASH BOYS by Wall Street chronicler Michael Lewis about speed, data, and alleged manipulation in financial markets. The controversy put high speed trading in the news, giving many of us in advertising pause to appre- ciate the parallels between our market and trading in financial markets. Since then, I have noted how problems related to speed and data can distort competition in other electronic trading markets, how lawmakers have monitored these markets for con- duct they frown upon in equities trading, but how advertising has largely remained off the same radar. This Article elaborates on these observations and curiosities. I am indebted to and thank the many journalists that painstakingly reported on industry conduct, the researchers and scholars whose work I cite, Fiona Scott Morton and Aus- tin Frerick at the Thurman Arnold Project for academic support, as well as Tom Fer- guson and the Institute for New Economic Thinking for helping to fund the research this project entailed. -

Ad Tech Inquiry: Issues Paper Response from Verizon Media

ACCC - Ad tech Inquiry: Issues Paper Response from Verizon Media Australia April 2020 1. Introduction 1.1. Verizon Media is pleased to provide these initial comments in response to the issues paper. We support competition authorities deepening their understanding of the digital advertising market, to fully understand the competitive dynamics and broader context - regulatory, contractual, and otherwise - within which competition takes place. 1.2. The inquiry impacts our business at all levels. Verizon Media is active in the advertising market as an advertiser, media owner and advertising intermediary. 2. About Verizon Media 2.1. Verizon Media is a global house of digital media and technology brands. Verizon Media’s brands include Yahoo, AOL, Ryot, HuffPost, TechCrunch and BUILD. Through our own operations, and in partnership with others, Verizon Media helps drive diversity and choice in consumer services and brand advertising. 2.2. Verizon Media is a business division of Verizon Communications Inc. Verizon Media operates in Australia as Verizon Media Australia Pty Ltd. 3. General comments 3.1. The digital advertising market provides benefits to both businesses and consumers. Revenue generated by digital advertising funds content creation and is critical for fueling investment in platforms, content creation and journalism. Competition in the ad intermediation market provides publishers the ability to partner with multiple platforms and to maximise the value of their inventory. In turn, this promotes plurality by providing a sustainable revenue stream for digital media. Consumers, in turn, reap the benefits of more diverse media. 3.2. We welcome the ACCC’s commitment to detailed evidence-gathering and analysis. -

Ronto Colostate 0053N 10925.Pdf (291.1Kb)

THESIS WHAT IS GOING ON IN THE BLOGOSPHERE: AN EXPLORATORY STUDY OF HOW CONSUMERS AND COMPANIES USE WEBLOGS IN THE MARKETING AND COMMUNICATION PROCESS Submitted by Paul Ronto Department of Journalism and Technical Communication In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Spring 2012 Master’s Committee : Advisor: Jamie Switzer Joseph Champ Joseph Cannon ABSTRACT WHAT IS GOING ON IN THE BLOGOSPHERE: AN EXPLORATORY STUDY OF HOW CONSUMERS AND COMPANIES USE WEBLOGS IN THE MARKETING AND COMMUNICATION PROCESS In the past few years weblogs have become a major channel for publishing content over the Internet. With the popularity of social media as a medium to communicate with consumers, companies around the world have started using weblogs as part of their communication strategy. However there remains a void of literature on company blogging, and users still do not have a solid understanding of how and why both consumers and companies are using this tool. This is an exploratory study into the world of company blogging, and it aims to add some insight as to what is going on in the blogosphere. Qualitative interviews were conducted with participants representing both the company and consumer perspective. The results indicate that although some companies believe having a blog is important, this belief is based more on blind faith in the medium than actual measurable data. The companies studied showed that their blogging strategy was very casual and the actual benefits to the company or consumer needs were not taken into account. From the consumer perspective, blogs were viewed as a tool to gather information and a place where a consumer would hopefully receive some sort of value for their time. -

Predicting Web Searcher Satisfaction with Existing Community-Based Answers

Predicting Web Searcher Satisfaction with Existing Community-based Answers Qiaoling Liu§, Eugene Agichtein§, Gideon Dror†, Evgeniy Gabrilovich‡, Yoelle Maarek†, Dan Pelleg†, Idan Szpektor†, §Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA †Yahoo! Research, Haifa, Israel ‡Yahoo! Research, Santa Clara, CA, USA {qliu26, eugene}@mathcs.emory.edu, {gideondr, gabr, yoelle, dpelleg, idan}@yahoo-inc.com ABSTRACT 1. INTRODUCTION Community-based Question Answering (CQA) sites, such “Just because Google exists doesn’t mean you should as Yahoo! Answers, Baidu Knows, Naver, and Quora, have stop asking people things.” – Alexia Tsotsis [35] been rapidly growing in popularity. The resulting archives Community-based Question Answering (CQA) sites, such of posted answers to questions, in Yahoo! Answers alone, as Yahoo! Answers, Baidu Knows, and Naver Ji-Sik-In, as already exceed in size 1 billion, and are aggressively indexed well as more social-oriented newcomers such as Vark and by web search engines. In fact, a large number of search Quora, have gained substantial popularity over the recent engine users benefit from these archives, by finding existing years, effectively filling a niche left by the mainstream Web answers that address their own queries. This scenario poses search engines. People around the globe resort to commu- new challenges and opportunities for both search engines nity help for a variety of reasons, from lack of proficiency in and CQA sites. To this end, we formulate a new problem of Web search to seeking an answer “with a human touch”. Al- predicting the satisfaction of web searchers with CQA an- though some of these sites allow for monetary payments in swers. -

China's Belt and Road

Independent Task Force Report No. 79 Report Force Task Independent China’s Belt and Road China’s Belt Independent Task Force Report No. 79 China’s Belt and Road March 2021 March Implications for the United States Jacob J. Lew and Gary Roughead, Chairs Jennifer Hillman and David Sacks, Project Directors Independent Task Force Report No. 79 China’s Belt and Road Implications for the United States Jacob J. Lew and Gary Roughead, Chairs Jennifer Hillman and David Sacks, Project Directors The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) is an independent, nonpartisan membership organization, think tank, and publisher dedicated to being a resource for its members, government officials, business executives, journalists, educators and students, civic and religious leaders, and other interested citizens in order to help them better understand the world and the foreign policy choices facing the United States and other countries. Founded in 1921, CFR carries out its mission by maintaining a diverse membership, with special programs to promote interest and develop expertise in the next generation of foreign policy leaders; convening meetings at its headquarters in New York and in Washington, DC, and other cities where senior government officials, members of Congress, global leaders, and prominent thinkers come together with Council members to discuss and debate major international issues; supporting a Studies Program that fosters independent research, enabling CFR scholars to produce articles, reports, and books and hold roundtables that analyze foreign policy issues and make concrete policy recommendations; publishing Foreign Affairs, the preeminent journal on international affairs and U.S. foreign policy; sponsoring Independent Task Forces that produce reports with both findings and policy prescriptions on the most important foreign policy topics; and providing up-to- date information and analysis about world events and American foreign policy on its website, CFR.org. -

US E-Commerce Sales to Jump 18% in 2020, but Not Enough to Offset Retail’S Decline | Techcrunch

9/22/2020 US e-commerce sales to jump 18% in 2020, but not enough to offset retail’s decline | TechCrunch US e-commerce sales to jumJopin E1xt8ra% in Login 2020, but not enough to offsCerutnc rhetail’s decline Sarah Perez Search @sarahintampa / 10:42 am EDT • June 8, 2020 Disrupt 2020 Startups Videos Disrupt Videos Audio Newsletters Extra Crunch The TC List Advertise Events — More Image Credits: Sari Montag / Flickr under a CC BY-SA 2.0 license. U.S. e-commerce sales will jump 18% this year due to the impact of the coronavirus pandemic that forced more shoppers online, according to a new forecast released today by eMarketer i . However, the surge in new online orders won’t make up for the overall hit that the U.S. retail sector will take this year, the firm noted. The analysts estimate that total U.S. retail sales, which also includes auto and fuel, will drop by 10.5% in 2020 to $4.894 trillion — a level not seen since 2016. This is also steeper than the 8.2% drop last seen in 2009, amid the recession. “This is the sharpest consumer spending freeze in decades in the U.S.,” said eMarketer senior forecasting analyst Cindy Liu, in a report. ‘In just a couple weeks, as Americans sheltered in place, retail sales fell dramatically in March. With sales hitting their lowest point https://techcrunch.com/2020/06/08/u-s-e-commerce-sales-to-jump-18-in-2020-but-not-enough-to-offset-retails-decline/ 1/10 9/22/2020 US e-commerce sales to jump 18% in 2020, but not enough to offset retail’s decline | TechCrunch of the year in Q2, it will take years before consumer activity returns to normal levels,” she predicted. -

Rank by Time Or by Relevance?

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301417684 Rank by Time or by Relevance? Conference Paper · January 2015 DOI: 10.1145/2806416.2806471 CITATIONS READS 0 15 5 authors, including: David Carmel Yoelle Maarek Yahoo Yahoo 112 PUBLICATIONS 3,248 CITATIONS 90 PUBLICATIONS 2,294 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by David Carmel on 02 January 2017. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. All in-text references underlined in blue are added to the original document and are linked to publications on ResearchGate, letting you access and read them immediately. Rank by Time or by Relevance? Revisiting Email Search David Carmel1, Guy Halawi2, Liane Lewin-Eytan2, Yoelle Maarek1, Ariel Raviv2 Yahoo Labs, MATAM Park Haifa, 31905, Israel 1fdavid.carmel,yoelle}@ymail.com, 2fghalawi,liane,arielr}@yahoo-inc.com ABSTRACT range from 15GB for Gmail to 1TB for Yahoo Mail. For With Web mail services offering larger and larger storage most users, cleaning up inboxes is not compulsory anymore, capacity, most users do not feel the need to systematically and they adopt the \lazy" approach of rarely deleting mes- delete messages anymore and inboxes keep growing. It is sages. We have verified over 2 months of users' activities in quite surprising that in spite of the huge progress of rele- Yahoo Web mail service, that 82% of users never deleted a vance ranking in Web Search, mail search results are still single message. Thus, mailboxes have grown and will keep typically ranked by date.