(Épilogue) AB 130 : Le Dossier Anton Bruckner The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saisonprogramm 2019/20

19 – 20 ZWISCHEN Vollendeter HEIMAT Genuss TRADITION braucht ein & BRAUCHTUM perfektes MODERNE Zusammenspiel KULTURRÄUME NATIONEN Als führendes Energie- und Infrastrukturunternehmen im oberösterreichischen Zentralraum sind wir ein starker Partner für Wirtschaft, Kunst und Kultur und die Menschen in der Region. Die LINZ AG wünscht allen Besucherinnen und Besuchern beste Unterhaltung. LINZ AG_Brucknerfest 190x245 mit 7mm Bund.indd 1 30.01.19 09:35 6 Vorworte 12 Saison 19/20 16 Abos 19/20 22 Das Große Abonnement 32 Sonntagsmatineen 42 Kost-Proben 44 Das besondere Konzert 100 Moderierte Foyer-Konzerte am Sonntagnachmittag 50 Chorkonzerte 104 Musikalischer Adventkalender 54 Liederabende 112 BrucknerBeats 58 Streichquartette 114 Russische Dienstage INHALTS- 62 Kammermusik 118 Musik der Völker 66 Stars von morgen 124 Jazz 70 Klavierrecitals 130 BRUCKNER’S Jazz 74 C. Bechstein Klavierabende 132 Gemischter Satz 80 Orgelkonzerte VERZEICHNIS 134 Comedy.Music 84 Orgelmusik zur Teatime 138 Serenaden 88 WortKlang 146 Kooperationen 92 Ars Antiqua Austria 158 Jugend 96 Hier & Jetzt 162 Kinder 178 Kalendarium 193 Team Brucknerhaus 214 Saalpläne 218 Karten & Service 5 Kunst und Kultur sind anregend, manchmal im flüge unseres Bruckner Orchesters genießen Hommage an das Genie Anton Bruckner Das neugestaltete Musikprogramm erinnert wahrsten Sinn des Wortes aufregend – immer kann. Dass auch die oberösterreichischen Linz spielt im Kulturleben des Landes Ober- ebenso wie das Brucknerfest an das kompo- aber eine Bereicherung unseres Lebens, weil Landesmusikschulen immer wieder zu Gast österreich ohne Zweifel die erste Geige. Mit sitorische Schaffen des Jahrhundertgenies sie die Kraft haben, über alle Unterschiedlich- im Brucknerhaus Linz sind, ist eine weitere dem internationalen Brucknerfest, den Klang- Bruckner, für den unsere Stadt einen Lebens- keiten hinweg verbindend zu wirken. -

Schubert: the Nonsense Society Revisited

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Schubert: The Nonsense Society Revisited RITA STEBLIN Twenty years have now passed since I discovered materials belonging to the Unsinnsgesellschaft (Nonsense Society).1 This informal club, active in Vienna from April 1817 to December 1818, consisted mainly of young painters and poets with Schubert as one of its central members. In this essay I will review this discovery, my ensuing interpretations, and provide some new observations. In January 1994, at the start of a research project on Schubert ico- nography, I studied some illustrated documents at the Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien (now the Wienmuseum am Karlsplatz), titled “Unsinniaden.”2 The documents comprise forty-four watercolor pictures and thirty-seven pages of text recording two festive events celebrated by the Nonsense Society: the New Year’s Eve party at the end of 1817 and the group’s first birthday party on 18 April 1818.3 The pictures depict various club members, identified by their code names and dressed in fan- ciful costumes, as well as four group scenes for the first event, including Vivat es lebe Blasius Leks (Long live Blasius Leks; Figure 1), and two group scenes for the second event, including Feuergeister-Scene (Fire Spirit Scene; Figure 6 below).4 Because of the use of code names—and the misidentifi- cations written on the pictures by some previous owner of the -

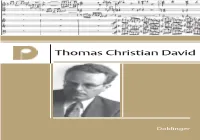

Thomas Christian David

Thomas Christian David Foto Seite 1: Kobé, Seite 3: Heinz Moser Notenbeispiel Seite 1: Thomas Christian David, Konzert für Orgel und Orchester Redaktion: Dr. Christian Heindl H/8-2007 d INFO-DOBLINGER, Postfach 882, A-1011 Wien Tel.: +43/1/515 03-33,34 Fax: +43/1/515 03-51 E-Mail: [email protected] 99 306 website: www.doblinger-musikverlag.at Doblinger Inhalt / Contents Biographie . 3 Biography . 4 Werke bei / Music published by Doblinger INSTRUMENTALMUSIK / INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC Flöte / Flute . 5 Klarinette / Clarinet . 5 Violine / Violin . 5 Klavier / Piano . 5 Orgel / Organ . 5 Violine und Klavier / Violin and piano . 6 Violoncello und Klavier / Cello and piano . 6 Duos und Kammermusik für Blasinstrumente / Duos and chamber music for wind instruments . 6 Duos und Kammermusik für Streichinstrumente / Duos and chamber music for string instruments . 7 Kammermusik für Gitarre / Chamber music for guitar . 8 Duos und Kammermusik für gemischte Besetzung / Duos and chamber music for mixed instruments . 8 Soloinstrument und Orchester / Solo instrument and orchestra . 10 Blasorchester / Wind orchestra . 11 Streichorchester / String orchestra . 12 Orchester / Orchestra . 12 VOKALMUSIK / VOCAL MUSIC Gesang und Klavier / Solo voice and piano . 12 Gesang und Orchester / Solo voice and orchestra . 13 Gemischter Chor a cappella / Unaccompanied choral music . 14 Gemischter Chor mit Begleitung / Accompanied choral music . 14 Kantate, Oratorium / Cantata, Oratorio . 15 Oper / Opera . 15 Abkürzungen / Abbreviations: L = Aufführungsmaterial leihweise / Orchestral parts for hire UA = Uraufführung / World premiere Nach den Werktiteln sind Entstehungsjahr und ungefähre Aufführungsdauer angegeben. Bei Or- chesterwerken folgt die Angabe der Besetzung der üblichen Anordnung in der Partitur. Käufliche Ausgaben sind durch Angabe der Bestellnummer links vom Titel gekennzeichnet. -

UNA VOCE March 2013 Vol

UNA VOCE March 2013 Vol. 20, No. 3 The Organization of Canadian Symphony Musicians (ocsm)isthe voice of Canadian professional orchestral musicians. ocsm’s mission is to uphold and improve the working conditions of professional Canadian orchestral musicians, to promote commu- nication among its members, and to advocate on behalf of the Canadian cultural community. Editorial Vancouver dispute leads to By Barbara Hankins new rights for symphonic Editor extra musicians Does it matter to music lovers how the orchestra By Matt Heller looks? Many will say that people see us before they ocsm President hear us, and that ‘‘visual cohesion’’ is of paramount importance. Others say that a change of dress code In recent years, Vancouver Symphony musicians have from the stuffy tails and white tie is needed to break toured China, opened a new School of Music, and won down the barrier between the orchestra and audience. aGrammy Award. Atthe negotiating table, vso musi- Arlene Dahl’s article gives a clear overview of the cians have fought to keep pace with the city’s booming choices musicians and managements are considering. economy and to recover from a 25 per cent salary cut If you have an opinion on this, feel free to chime in on in 2000. The Vancouver Symphony’s last agreement the ocsm list or send me your thoughts for possible finished with the 2011–12 season, so negotiations use in the next Una Voce. should have begun last spring. What happened instead My personal view is was a contentious and complex dispute between the that while the dress vso Musicians Association (vsoma), and the Vancou- code should reflect our ver Musicians Association (vma), the afm Local repre- respect for our art and senting all unionized Vancouver musicians, including the tone of the concert, those in the vso. -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

Download Booklet

© Manu Theobald 1 FRIEDRICH CERHA (*1926) Eine Art Chansons Teil I Teil II 1 Statt Ouvertüre [Instead of an Overture] 1:27 18 ich bekreuzige mich [I cross myself] Ernst Jandl 0:34 2 hörprobe [audition] Ernst Jandl 0:57 19 lichtung [(d)irection] Ernst Jandl 0:20 3 sonett [sonnett] Gerhard Rühm 0:42 20 fragment Ernst Jandl 0:30 4 Klatsch [Gossip] Horst Beinek 0:15 21 österreichisches fragment [austrian fragment] Friedrich Cerha 0:34 5 Zungentraining [Tounge training] Brigitte Peter 0:18 22 ich brech dich [i‘ll break you] Ernst Jandl 0:18 6 Klassisch [Classic] Hermann Jandl 0:22 23 Waschmaschinen [Washing Machine] Beat Brechbühl 0:24 7 ein deutsches denkmal [A German Monument] Ernst Jandl 1:09 24 thechdthen jahr [sixteenth year] Ernst Jandl 0:46 8 Kleines Gedicht für große Stotterer 25 falamaleikum Ernst Jandl 0:32 [Small Poem for Big Stutterers] Kurt Schwitters 1:28 26 loch [laugh/hole] Ernst Jandl 0:29 9 Epitaph Klabund 1:10 27 wien: heldenplatz [vienna: heldenplatz] Ernst Jandl 1:03 10 Wenn der Puls [When the Pulse] anonymous 0:38 28 13. märz [March 13] Ernst Jandl 1:08 11 Mazurka (nach Satie) [Mazurka (after Satie)] 1:11 29 keiner schließlich [no one finally] Ernst Jandl 0:26 12 Vierzeiler [Quatrain] Werner Finck 0:57 30 vater komm erzähl vom krieg 13 sieben Kinder [seven Children] Ernst Jandl 0:33 [father come tell me about the war] Ernst Jandl 0:52 14 Die Wühlmaus [The Vole] Fred Endrikat 0:57 31 was können sie dir tun [what can they do to you] Ernst Jandl 1:18 15 Puppenmarsch [Doll March] 0:38 32 koexistenz [coexist] Ernst Jandl 1:18 -

Franz Schubert: Inside, out (Mus 7903)

FRANZ SCHUBERT: INSIDE, OUT (MUS 7903) LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY, COLLEGE OF MUSIC & DRAMATIC ARTS FALL 2017 instructor Dr. Blake Howe ([email protected]) M&DA 274 meetings Thursdays, 2:00–4:50 M&DA 273 office hours Fridays, 9:30–10:30 prerequisite Students must have passed either the Music History Diagnostic Exam or MUS 3710. Blake Howe / Franz Schubert – Syllabus / 2 GENERAL INFORMATION COURSE DESCRIPTION This course surveys the life, works, and times of Franz Schubert (1797–1828), one of the most important composers of the nineteenth century. We begin by attempting to understand Schubert’s character and temperament, his life in a politically turbulent city, the social and cultural institutions that sponsored his musical career, and the circles of friends who supported and inspired his artistic vision. We turn to his compositions: the influence of predecessors and contemporaries (idols and rivals) on his early works, his revolutionary approach to poetry and song, the cultivation of expression and subjectivity in his instrumental works, and his audacious harmonic and formal practices. And we conclude with a consideration of Schubert’s legacy: the ever-changing nature of his posthumous reception, his impact on subsequent composers, and the ways in which modern composers have sought to retool, revise, and refinish his music. COURSE MATERIALS Reading assignments will be posted on Moodle or held on reserve in the music library. Listening assignments will link to Naxos Music Library, available through the music library and remotely accessible to any LSU student. There is no required textbook for the course. However, the following texts are recommended for reference purposes: Otto E. -

Cyberarts 2018

Hannes Leopoldseder · Christine Schöpf · Gerfried Stocker CyberArts 2018 International Compendium Prix Ars Electronica Computer Animation · Interactive Art + · Digital Communities Visionary Pioneers of Media Art · u19–CREATE YOUR WORLD STARTS Prize’18 Grand Prize of the European Commission honoring Innovation in Technology, Industry and Society stimulated by the Arts INTERACTIVE ART + Navigating Shifting Ecologies with Empathy Minoru Hatanaka, Maša Jazbec, Karin Ohlenschläger, Lubi Thomas, Victoria Vesna Interactive Art was introduced to Prix Ars Electronica farewell and prayers of a dying person into the robot as a key category in 1990. In 2016, in response to a software; seeking life-likeness—computational self, growing diversity of artistic works and methods, the and environmental awareness; autonomous, social, “+” was added, making it Interactive Art +. and unpredictable physical movement; through to Interactivity is present everywhere and our idea of the raising of a robot as one's own child. This is just what it means to engage with technology has shifted a small sample of the artificial ‘life sparks’ in this from solely human–machine interfaces to a broader year’s category. Interacting with such artificial enti- experience that goes beyond the anthropocentric ties draws us into both a practical and ethical dia- point of view. We are learning to accept machines as logue about the future of robotics, advances in this other entities we share our lives with while our rela- field, and their role in our lives and society. tionship with the biological world is intensified by At the same time, many powerful works that deal the urgency of environmental disasters and climate with social issues were submitted. -

Jury Streichquartett

Kurt Schwertsik Geboren 1935 in Wien. Kompositionsstudien bei Joseph Marx und Karl Schiske an der Wiener Musikakademie sowie bei Gottfried Freiberg. Weiterführende Studien in Darmstadt und Köln bei Karlheinz Stockhausen, Mauricio Kagel und John Cage. Erste Stelle als Hornist beim Niederösterreichischen Tonkünstlerorchester, danach bei den Wiener Symphonikern. 1958 zusammen mit seinem Komponistenfreund Friedrich Cerha Gründung des Ensembles "die reihe", 1965 Organisation der ersten "Salonkonzerte" in Wien mit Otto M. Zykan, 1968 zusammen mit Zykan und Heinz Karl Gruber Gründung des Ensembles "MOB art & tone ART", für das u. a. die "Symphonie im MOB-Stil op. 19" entstand. Nach einer Gastprofessur für Komposition und Analyse an der University of California in Riverside (1966) Kompositionslehrer am Wiener Konservatorium, dann Gastprofessor und ab 1989 ordentlicher Professor für Komposition an der Hochschule für Musik und darstellende Kunst Wien. Zahlreiche Kompositionsaufträge, Werkpräsentationen und Aufführungen, u. a. bei den Darmstädter Ferienkursen, der EXPO in Montréal, im steirischen herbst, den Wiener Festwochen, den Salzburger Festspielen. Zahlreiche Preise und Auszeichnungen: Würdigungspreis der Republik Österreich (1974), Musikpreis der Stadt Wien (1980) und Großer Österreichischer Staatspreis (1992). Born in Vienna in 1935, studied composition with Joseph Marx and Karl Schiske at the Vienna Academy of Music and with Gottfried Freiberg. He continued studies in Darmstadt and Cologne with Karlheinz Stokhausen, Mauricio Kagel and John Cage. First position as french hornist in the Niederösterreichische Tonkünstlerorchester, then with the Wiener Symphoniker. In 1958 he founded the New Music ensemble "die reihe" together with his fellow composer Friedrich Cerha. In 1965 organisation of the first "Salonkonzerte" in Vienna together with Otto M. Zykan. -

2005 Next Wave Festival

November 2005 2005 Next Wave Festival Mary Heilmann, Last Chance for Gas Study (detail), 2005 BAM 2005 Next Wave Festival is sponsored by: The PerformingNCOREArts Magazine Altria 2005 ~ext Wave FeslliLaL Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman William I. Campbell Chairman of the Board Vice Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins Joseph V. Melillo President Executive Prod ucer presents Symphony No.6 (Plutonian Ode) & Symphony No.8 by Philip Glass Bruckner Orchestra Linz Approximate BAM Howard Gilman Opera House running time: Nov 2,4 & 5, 2005 at 7:30pm 1 hour, 40 minutes, one intermission Conducted by Dennis Russell Davies Soprano Lauren Flanigan Symphony No.8 - World Premiere I II III -intermission- Symphony No. 6 (Plutonian Ode) I II III BAM 2005 Next Wave Festival is sponsored by Altria Group, Inc. Major support for Symphonies 6 & 8 is provided by The Robert W Wilson Foundation, with additional support from the Austrian Cultural Forum New York. Support for BAM Music is provided by The Aaron Copland Fund for Music, Inc. Yamaha is the official piano for BAM. Dennis Russell Davies, Thomas Koslowski Horns Executive Director conductor Gerda Fritzsche Robert Schnepps Dr. Thomas Konigstorfer Aniko Biro Peter KeserU First Violins Severi n Endelweber Thomas Fischer Artistic Director Dr. Heribert Schroder Heinz Haunold, Karlheinz Ertl Concertmaster Cellos Walter Pauzenberger General Secretary Mario Seriakov, Elisabeth Bauer Christian Pottinger Mag. Catharina JUrs Concertmaster Bernhard Walchshofer Erha rd Zehetner Piotr Glad ki Stefa n Tittgen Florian Madleitner Secretary Claudia Federspieler Mitsuaki Vorraber Leopold Ramerstorfer Elisabeth Winkler Vlasta Rappl Susanne Lissy Miklos Nagy Bernadett Valik Trumpets Stage Crew Peter Beer Malva Hatibi Ernst Leitner Herbert Hoglinger Jana Mooshammer Magdalena Eichmeyer Hannes Peer Andrew Wiering Reinhard Pirstinger Thomas Wall Regina Angerer- COLUMBIA ARTISTS Yuko Kana-Buchmann Philipp Preimesberger BrUndlinger MANAGEMENT LLC Gorda na Pi rsti nger Tour Direction: Gudrun Geyer Double Basses Trombones R. -

Bläserphilharmonie Mozarteum Salzburg

BLÄSERPHILHARMONIE MOZARTEUM SALZBURG DANY BONVIN GALACTIC BRASS GIOVANNI GABRIELI ERNST LUDWIG LEITNER RICHARD STRAUSS ANTON BRUCKNER WERNER PIRCHNER CD 1 WILLIAM BYRD (1543–1623) (17) Station XIII: Jesus wird vom Kreuz GALAKTISCHE MUSIK gewesen ist. In demselben ausgehenden (1) The Earl of Oxford`s March (3'35) genommen (2‘02) 16. Jahrhundert lebte und wirkte im Italien (18) Station XIV: Jesus wird ins „Galactic Brass“ – der Titel dieses Pro der Renaissance Maestro Giovanni Gabrieli GIOVANNI GABRIELI (1557–1612) Grab gelegt (1‘16) gramms könnte dazu verleiten, an „Star im Markusdom zu Venedig. Auf den einander (2) Canzon Septimi Toni a 8 (3‘19) Orgel: Bettina Leitner Wars“, „The Planets“ und ähnliche Musik gegenüber liegenden Emporen des Doms (3) Sonata Nr. XIII aus der Sterne zu denken. Er meint jedoch experimentierte Gabrieli mit Ensembles, „Canzone e Sonate” (2‘58) JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACh (1685–1750) Kom ponisten und Musik, die gleichsam ins die abwechselnd mit und gegeneinander (19) Passacaglia für Orgel cMoll, BWV 582 ERNST LUDWIG LEITNER (*1943) Universum der Zeitlosigkeit aufgestiegen musizierten. Damit war die Mehrchörigkeit in der Fassung für acht Posaunen sind, Stücke, die zum kulturellen Erbe des gefunden, die Orchestermusik des Barock Via Crucis – Übermalungen nach den XIV von Donald Hunsberger (6‘15) Stationen des Kreuzweges von Franz Liszt Planeten Erde gehören. eingeleitet und ganz nebenbei so etwas für Orgel, Pauken und zwölf Blechbläser, RICHARD STRAUSS (1864–1949) wie natürliches Stereo. Die Besetzung mit Uraufführung (20) Feierlicher Einzug der Ritter des William Byrd, der berühmteste Komponist verschiedenen Blasinstrumenten war flexibel JohanniterOrdens, AV 103 (6‘40) Englands in der Zeit William Shakespeares, und wurde den jeweiligen Räumen ange (4) Hymnus „Vexilla regis“ (1‘12) hat einen Marsch für jenen Earl of Oxford passt. -

Kevin John Crichton Phd Thesis

'PREPARING FOR GOVERNMENT?' : WILHELM FRICK AS THURINGIA'S NAZI MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR AND OF EDUCATION, 23 JANUARY 1930 - 1 APRIL 1931 Kevin John Crichton A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2002 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/13816 This item is protected by original copyright “Preparing for Government?” Wilhelm Frick as Thuringia’s Nazi Minister of the Interior and of Education, 23 January 1930 - 1 April 1931 Submitted. for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of St. Andrews, 2001 by Kevin John Crichton BA(Wales), MA (Lancaster) Microsoft Certified Professional (MCP) Microsoft Certified Systems Engineer (MCSE) (c) 2001 KJ. Crichton ProQuest Number: 10170694 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10170694 Published by ProQuest LLO (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author’. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLO. ProQuest LLO. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.Q. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 CONTENTS Abstract Declaration Acknowledgements Abbreviations Chapter One: Introduction 1 Chapter Two: Background 33 Chapter Three: Frick as Interior Minister I 85 Chapter Four: Frick as Interior Ministie II 124 Chapter Five: Frickas Education Miannsti^r' 200 Chapter Six: Frick a.s Coalition Minister 268 Chapter Seven: Conclusion 317 Appendix Bibliography 332.