The Feng Shui Detective Books

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Channel U

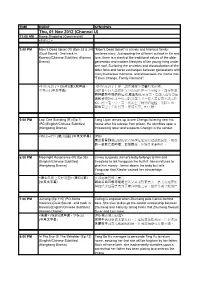

TIME EVENT SYNOPSIS Sat, 01 Sep 2012 (Channel U) 6:00 AM Home Shopping (Commercial) <购物乐> 10:00 AM Million Singer (R) (Variety) "Million Singer" is currently one of the top variety shows in Taiwan. Hosted by Harlem Yu, the programme invites famous singers to take part in "Remember the Song Lyrics Contest" every week. Winners stand to win the grand prize of NT$1,000,000. <百万大歌星> (综艺节目)(重) <百万大歌星>是目前台湾最新最热门的综艺节目。主持人庾 澄庆每期都会邀请许多艺人来参加歌唱游戏, 考验他们背记歌词的功力。如果他们一路过关斩将, 就可赢取一百万元奖金。 11:30 AM Wonders of Horus (R) (Dual Sound - 2nd track in Japanese)(Chinese Subtitles) (Variety) <科学大不同> (综艺节目)(重)(双声道 - 华日语) (中文字幕) 12:00 PM Unique Discovery (Info/Education) "Unique Discovery" is a unique delicacies programme that introduces China's top local delights. Through news reporting, it provides the audiences with an accurate and realistic introduction of these local dishes. Host: Li Wenjuan <非凡大探索> (资讯节目) 《非凡大探索》这个美食节目利用近似新闻报导的方式去介 绍中国各地的美食小吃,让观众们亲身品尝之后少有"报导 不实"的感觉。 主持人:李文娟 1:00 PM Sunday Splendid Showtime (R) Have fun with Zeng Guo Cheng, Blackie Chen and Tammy (Variety) Chen in this awesome variety show! Celebrities are split into two teams in a Red vs White segment where their singing, dancing and impersonation skills are challenged. <周日大精彩> (综艺节目)(重) 由曾国城、陈建州(黑人)和陈怡蓉主持的娱乐性丰富综艺 节目。在"红白大赏"单元里,每一集曾国城和黑人会分别带 领一班艺人,在舞蹈、歌唱、模仿等各方面互相竞技,争取 胜利。 2:00 PM Super Taste (R) (Infotainment) <时尚玩家 - 就要酱玩> (娱乐资讯节目)(重) 3:00 PM Pink Lipstick (PG) (R) (Eps 1 & 2) Jia'en is delighted to know that her best friend, Meilan will (Dual Sound - 2nd track in be returning from the States. When the day comes, Jia'en Korean)(English/Chinese Subtitles) goes to receive Meilan at the airport. -

Australian Journal of Applied Linguistics Interpersonal Meaning

OPEN ACCESS Australian Journal of Applied Linguistics ISSN 2209-0959 https://journals.castledown-puBlishers.com/ajal/ Australian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 1 (1), 3-19 (2018) https://dx.doi.org/10.29140/ajal.v1n1.4 Interpersonal Meaning of Code-switching: An Analysis of Three TV Series WANG HUABIN a a Department of English, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Email: [email protected] Abstract As one of the most widespread linguistic phenomena, code-switching has attracted increasing attention nowadays. Inspired by previous studies in this field, this paper addresses code-switching under the guidance of Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL), with the primary goal of analysing the interpersonal meanings of code-switching in three TV series. The research data were collected as follows: first, internet resources were examined to find three popular TV series with code-switching, namely I Not Stupid, Moonlight Resonance and Humble Abode; second, the data were selected, classified and observed for analysis. As the focus of this paper is interpersonal meaning, functional theories were elaborated towards a single framework for interpersonal meanings of code-switching in two parts: appraisal theory and tenor in register. The first part aims to evaluate emotions which are embedded in code-switching. The second part deals with the roles and relationships between different participants. With these theories included in the research, qualitative analyses were conducted: first of all, sample data were categorised based on their grammatical structures; then interpersonal meanings of code-switching are discussed under the guidance of these functional theories to test the applicability of SFL in this field. -

Channel U

TIME EVENT SYNOPSIS Mon, 01 Oct 2012 (Channel U) 11:00 AM Home Shopping (Commercial) <购物乐> 3:00 PM Money Week (R) (Local Current Tung Soo Hua hosts Money Week, the Mandarin Business Affairs) Current Affairs Programme, that provides comprehensive insights and analysis of the business world. <财经追击> (本地时事节目)(重) 《财经追击》是新加坡唯一以中文制作的经济时事节目。节 目将深入分析最新的经济趋势和商业动态,让观众能更好地 掌握市场走势和投资情报。 3:30 PM P.R.D. Walker (R) (Info/Education) In this series of travelogues, host Leung Ka Ki and Karman Cheng takes us through the many interesting places throughout China's Pearl River Delta. <潮游珠三角> (资讯节目)(重) 在这系列旅游记事里, 让主持人梁嘉琪与郑嘉雯带我们潮游珠三角. 4:00 PM The Stories In China (R) Hosted by Cai Li Qun and Ken, "Stories of China" is a fun (Infotainment) and adventurous travelogue that takes its viewers to the different parts of China. From cultural to traditional activities, each episode features the most authentic aspects of China ever as Li Qun shares with the viewers stories about the place visited and its people. <在中国的故事> (娱乐资讯节目)(重) 最真实的中国,最动人的故事! 让节目主持人蔡立群与阿Ken,带大家去见识中国各地多姿 多彩的文化与习俗,品尝各种风味不同的地方美食,以及与 观众分享一些鲜为人知的民间轶事。 5:00 PM Angel Lover (R) (Ep 9) (Taiwan As members of an organisation called "Angel Lover", a Drama) group of five young men devote themselves to helping women, who have troubles in their relationships with men, to rediscover the true meaning of love and to regain confidence in life. <天使情人> (台湾剧)(重) 曾经为爱伤痛的Angelina, 成立了一个名叫"Angel Lover"的组织。这个组织有五个男生, 他们愿意付出自己的关心和智慧, 帮助那些在感情上受过伤害的女人,重新获得爱与生命的勇 气。 6:00 PM Moonlight Resonance (R) (Ep 12) Taizu's mum goes on a hunger strike when Yongzhong (English/Chinese Subtitles) and Yongjia refuse to return home. -

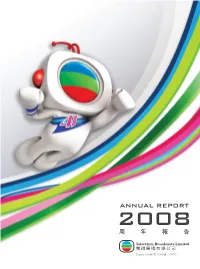

2008 Annual Report

Highlights Turnover & Profit Attributable to Equity 2008 2007 Change Holders of the Company Turnover Profit Attributable to Equity Holders of the Company Financial Highlights Performance 5,000 Earnings per share HK$2.41 HK$2.89 -17% Dividend per share – Interim HK$0.30 HK$0.30 – 4,000 – Final HK$1.40 HK$1.50 -7% HK$1.70 HK$1.80 -6% 3,000 For the year HK$’ mil HK$’ mil Turnover HK$’ mil – Terrestrial television broadcasting 2,346 2,373 -1% 2,000 – Programme licensing and distribution 773 743 +4% – Overseas satellite pay TV operations 289 281 +3% – Channel operations 1,065 965 +10% 1,000 – Other activities 107 101 +6% – Inter-segment elimination (173 ) (137 ) +26% 4,407 4,326 +2% 0 20042005 2006 2007 2008 YEAR Total expenses (3,102 ) (2,787 ) +11% Share of losses of associates (63 ) (125 ) -50% Profit attributable to equity holders 1,055 1,264 -17% Earnings & Dividends Per Share Earnings per Share Dividends per Share As at 31 December Total assets 6,742 6,251 +8% 3.5 Total liabilities 1,108 882 +26% Total equity 5,634 5,369 +5% 3 Number of issued shares 438,000,000 438,000,000 2.5 Ratios Current ratio 5.34 5.42 Gearing 6% – 2 HK$ Operational Highlights 1.5 Average audience share Weekday prime time – Jade 85% 84% 1 Weekly prime time – Pearl 75% 79% 0.5 Number of terrestrial TV channels in Hong Kong 5 * 3 0 20042005 2006 2007 2008 * as of 25 Mar 2009 YEAR 2008 Turnover by Business Segment 2008 Segment Results by Business Segment Terrestrial television Terrestrial television broadcasting 53% (55%) broadcasting 47% (62%) Programme licensing -

João Gilberto

SEPTEMBER 2019 VOLUME 86 / NUMBER 9 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

Nury Vittachi

NURY VITTACHI The lighter Side of Business: Funny, Quirky and Highly Original NURY VITTACHI The lighter side of business Nury Vittachi was born in Sri Lanka whose family one night escaped the communal violence under the cover of darkness and spent many years traveling as nomads. He eventually settled in Hong Kong. Nury Vittachi has informed and entertained millions of people through various media; numerous regular television appearances, regular radio broadcasts and literally thousands of columns in dozens of periodicals. But he is best known for his offbeat thriller novel series The Feng Shui Detective which has been published many languages around the world. He has since published other books and novels. Nury regularly speaks at business forums about the peculiar things we do and say, cross-cultural idiosyncrasies and provides his audiences with a unique, off-beat humour. He is also a Master of Ceremonies at awards and conference social functions. NURY VITTACHI The Art of Story-Telling in Business “The art of telling stories is the deliberate use of narrative to achieve practical outcomes for individuals, within communities and for businesses.” In a world where we’re all constantly deluged with unrelated points of information, how do you stand out? Well, by having a tale to tell. By assembling your key points into a story, you’ll achieve memorability, likeability and a great deal more. Tales create a vital emotional bond. Leaders don’t get into top positions without ‘stories’ as pedestals. Marketing professionals now realize that a brand is more than a mere logo -- it needs to encapsulate a story. -

Time Event Synopsis

TIME EVENT SYNOPSIS Thu, 01 Nov 2012 (Channel U) 11:00 AM Home Shopping (Commercial) <购物乐> 3:00 PM Mom's Dead Upset (R) (Eps 23 & 24) "Mom's Dead Upset" is a lively and hilarious family- (Dual Sound - 2nd track in centered story. Juxtaposing the different outlook in life and Korean)(Chinese Subtitles) (Korean love, there is a clash of the traditional values of the older Drama) generation and modern lifestyles of the young living under one roof. Surfacing the anxieties and dissatisfaction of the older folks and harsh exchanges between generations with many humorous moments, and showcases the theme that "Times Change, Family Remains". <妈妈发怒了> (韩剧)(重)(双声道 - 《妈妈发怒了》是一部充满爆笑温馨的家庭剧. 华韩语) (中文字幕) 讲述着年轻人虽然和父母们同住在一个屋檐下,却存在着 两种截然不同的价值观,看法和处事方式。年轻人在对待生 活和爱情的追求令保守的父母等老一辈人看着既不满又担 心。剧中老、中、青三代发生了剧烈的碰撞,笑料百出, 却也带出了「时代变,亲情不变」的主题。 5:00 PM Last One Standing (R) (Ep 1) Tang Liyan tenses up to see Chengxi loitering near his (PG)(English/Chinese Subtitles) house after his release from prison. He stumbles upon a (Hongkong Drama) threatening letter and suspects Chengxi is the sender. <与敌同行> (港剧)(重) (中英文字幕) (PG) 唐立言看到刚出狱的承希徘徊在他家附近感到紧张,再收 到一封死亡恐吓信,更加慌张,怀疑是承希所作。 6:00 PM Moonlight Resonance (R) (Ep 35) Jimmy suspects Jiamei's baby belongs to him and (English/Chinese Subtitles) threatens to tell Yongyuan the truth if Jiamei refuses to (Hongkong Drama) give him money. Jiamei aborts the baby but tells Yongyuan that Xiaohe caused her miscarriage. Jimmy. <溏心风暴之家好月圆> (港剧)(重) 发现嘉美已嫁入豪门, (中英文字幕) 因此以自己极可能是婴儿父亲来勒索嘉美。嘉美决定堕胎 以绝后患但嘉美竟为了掩饰堕胎之事,指责笑荷令她流产 。 7:00 PM Jumong (Ep 115) (PG-Some Cailing is angered when Zhumeng puts Canxiu behind Violence)(Dual Sound - 2nd track in bars. -

©2016 Tara Coleman ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

©2016 Tara Coleman ALL RIGHTS RESERVED RE-VISIONS OF THE PAST: LYRICISM AS HISTORY IN CONTEMPORARY CHINESE POETRY AND FILM by TARA COLEMAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School – New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Comparative Literature Written under the direction of Weijie Song And approved by _________________________________ _________________________________ _________________________________ _________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey October, 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Re-visions of the Past: Lyricism as History in Contemporary Chinese Poetry and Film By TARA COLEMAN Dissertation Director: Weijie Song This dissertation investigates the role of lyricism in mainland Chinese and Taiwanese poetry and film. The project centers on the directors Hou Hsiao-hsien and Jia Zhangke, whose films are frequently described as lyrical despite their detailed, realistic recreation of the past. The analysis of these filmmakers is paired with chapters dealing with poetry by Ya Xian, Bei Dao, Xi Chuan and others. Drawing on concepts from both the Chinese and Western traditions, the dissertation identifies key poetic strategies that are operative in the films while taking into account the particularities of each medium. Lyricism is a flexible term that has been applied variously to these poems and films in an attempt to capture the way they translate the affective layers of historical experience into comprehensible artistic forms. Much more than a genre or style, lyricism is the result of a particular activation of the reader or spectator, who must participate in the meaning- making process and therefore bring something of his or her own emotional and personal resources to the work. -

{PDF EPUB} Heavenly Sword Prima Official Game Guide by Doublejump Productions Heavenly Sword: Prima Official Game Guide by Doublejump Productions

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Heavenly Sword Prima Official Game Guide by Doublejump Productions Heavenly Sword: Prima Official Game Guide by Doublejump Productions. Darksiders Iii also available in docx and mobi. Read Darksiders Iii online, read in mobile or Kindle. The Art of Darksiders III. Author : Thq. Publisher: Udon Entertainment. Download Now. Darksiders III. Official Collector's Edition Guide. Author : Doug Walsh. Publisher: Prima Games. Category: Art. Download Now. Focus On: 100 Most Popular Unreal Engine Games. Author : Wikipedia contributors. Publisher: e-artnow sro. Download Now. The Walkthrough. Insider Tales from a Life in Strategy Guides. Author : Doug Walsh. Publisher: Snoke Valley Books. Category: Computers. Download Now. Darksiders 3 Game, Walkthrough, Armor, Wiki, Gameplay, Bosses, Tips, Cheats, Jokes, Builds, Guide Unofficial. Author : Master Gamer. Publisher: Hiddenstuff Entertainment LLC. Category: Games & Activities. Download Now. Darksiders: The Abomination Vault. Author : Ari Marmell. Publisher: Del Rey. Category: Fiction. Download Now. Notebook. Darksiders 3 Fury , Journal for Writing, College Ruled Size 6 X 9 , 110 Pages. Author : DarksidersFf Notebook. Download Now. Notebook. Darksiders 3 Fury , Journal for Writing, College Ruled Size 6 X 9 , 110 Pages. Author : Darksidersm Notebook. Download Now. Darksiders II: Death's Door #3. Author : Andrew Kreisberg. Publisher: Dark Horse Comics (Single Issues) Category: Comics & Graphic Novels. Download Now. Game Informer Magazine. For Video Game Enthusiasts. Category: Computer games. Download Now. Becoming a Video Game Artist. From Portfolio Design to Landing the Job. Author : John Pearl. Publisher: CRC Press. Category: Computers. Download Now. Comics Values Annual. The Comic Book Price Guide. Author : Alex G. Malloy. Publisher: Krause Publications Incorporated. Category: Antiques & Collectibles. -

Starhub TVB Awards Presentation” in Singapore Raymond Lam and Charmaine Sheh Emerged the Biggest Winners of the Night

Press Release 4th February 2010 The inaugural “StarHub TVB Awards Presentation” in Singapore Raymond Lam and Charmaine Sheh emerged the biggest winners of the night The highly anticipated StarHub TVB Awards Presentation was successfully held on January 29, Friday at 8pm, at The Ritz-Carlton Millenia Hotel in Singapore. In celebration of the 18 years of close partnership between TVB and StarHub, the two giant broadcasters joined hands to organize the first ever StarHub TVB Awards, aiming to reward TVB‟s high quality programmes and celebrated stars. Raymond Lam and Charmaine Sheh, stole the hearts of many Singaporean fans, were named My Favourite TVB Actor and Actress. The renowned Singapore radio presenter Wenhong Huang and 2001 Miss Hong Kong Pageant Second Runner-up Heidi Chu were invited to host the award show. Mr. Stephen Chan, General Manager of Broadcasting, Television Broadcasts Limited, together with ten top-notch TVB stars including Moses Chan, Raymond Lam, Roger Kwok, Steven Ma, Wayne Lai, Susanna Kwan, Charmaine Sheh, Sonija Kwok, Fala Chen and Nancy Sit were in full dress to attend the ceremony. Ahead of the show, they appeared in pairs and strolled along the „green paparazzi walk‟ where fans were screaming and media cameras kept flashing. After the two-month long voting campaign, a buzz has been created among Singaporean fans and media on their favourite TVB dramas and artistes. Finally, a total of 18 awards were presented at the show (details please refer to the awardees list attached). Moonlight Resonance, one of the best-hit TVB dramas, has won excellent reception in Singapore since its release. -

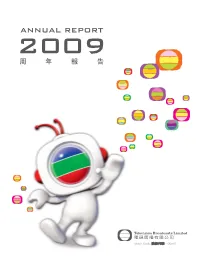

2009 Annual Report

FFinancialinancial HHighlightsighlights Turnover & Profit Attributable to 2009 2008 Change Equity Holders of the Company Turnover Profit Attributable to Equity Holders of the Company Performance 5,000 Earnings per share HK$2.06 HK$2.41 -15% Dividends per share - Interim HK$0.25 HK$0.30 -17% 4,000 - Final HK$1.35 HK$1.40 -4% HK$1.60 HK$1.70 -6% 3,000 HK$’mil HK$’mil Turnover HK$’ mil 2,000 - Hong Kong terrestrial television broadcasting 2,072 2,346 -12% - Programme licensing and 1,000 distribution 667 728 -8% - Overseas satellite pay TV operations 348 346 +1% 0 - Taiwan operations 630 720 -13% 20052006 2007 2008 2009 YEAR - Channel operations 329 344 -4% - Other activities 97 107 -9% - Inter-segment elimination (160 ) (184 ) -13% Earnings & Dividends Per Share 3,983 4,407 -10% Earnings per Share Dividends per Share Total expenses (2,741 ) (3,102 ) -12% 3.5 Share of losses of associates (65 ) (63 ) +3% Profit attributable to equity holders 900 1,055 -15% 3 2.5 31 December 31 December 2009 2008 2 HK$’mil HK$’mil HK$ Total assets 7,043 6,742 +4% 1.5 Total liabilities 1,224 1,108 +11% Total equity 5,819 5,634 +3% 1 Number of issued shares 438,000,000 438,000,000 0.5 Ratios Current ratio 4.39 5.34 0 20052006 2007 2008 2009 Gearing 5% 6% YEAR 2009 Turnover by Operating Segment 2009 Reportable Segment Profit by Operating Segment Hong Kong terrestrial television Hong Kong terrestrial television broadcasting 52% (53%) broadcasting 44% (47%) Programme licensing and Programme licensing and distribution 14% (13%) distribution 31% (28%) Overseas satellite -

CONGRATULATIONS—PROMAX|BDA WORLD GOLD DESIGN AWARD WINNERS *Entries Are Listed As Entered

BDA design award booklet 2009:Layout 1 6/10/09 1:50 AM Page 10 CONGRATULATIONS—PROMAX|BDA WORLD GOLD DESIGN AWARD WINNERS *Entries are listed as entered INTEGRATED MEDIA INTEGRATED MEDIA Bronze (Certificate) LOGO DESIGN: NETWORK/ CAMPAIGN DESIGN: TOPICAL StarHub UEFA EURO 2008 STATION ALL MEDIA ON-AIR StarHub Cable Vision Silver Silver INTEGRATED MEDIA 1st. Channel Georgia, Logo MTV Music Video Hours NETWORK PACKAGE DESIGN: Design MTV Japan Inc. IMAGE ON-AIR UnitedSenses Bronze (Certificate) Gold Bronze (Certificate) Clipmania Idents Cult Flipbooks Animal Planet Rebrand: Logo DW-TV Fox Channels Italy Animal Planet Bronze (Certificate) Silver Space Week Idents and Space INTEGRATED MEDIA Ztele - Package design Week Promo CAMPAIGN DESIGN: IMAGE ON- Ztele, A Station of Astral Media Nat Geo Uk + Brothers & Sisters AIR AND PRINT COMBINATION Silver Bronze (Certificate) Gold BBC Knowledge Idents The Sopranos MTV Australia Branding BBC Worldwide Warner Channel MTV Networks Australia Silver Silver INTEGRATED MEDIA MTV Australia Branding Id Icons FTV and Calendar CAMPAIGN DESIGN: TOPICAL ON- MTV Turner International Argentina AIR AND PRINT COMBINATION Bronze (Certificate) Bronze (Certificate) Gold Fox Rebrand CNN=Politics Martial Artist Troika Design Group CNN NBC Universal Global INTERACTIVE MEDIA Bronze (Certificate) Networks Germany E-COMMUNICATIONS Arte Redesign 2008 Silver Luxlotusliner GmbH A Lamp Is a Princess Bronze (Certificate) OnceTV TV1 What's Hot eNewsletter INTEGRATED MEDIA TV1 Bronze (Certificate) CAMPAIGN DESIGN: NEWS ALL Gossip Girl