Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prelude | Grove Music

Prelude (Fr. prélude; Ger. Vorspiel; It., Sp. preludio; Lat. praeludium, praeambulum) David Ledbetter and Howard Ferguson https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.43302 Published in print: 20 January 2001 Published online: 2001 updated and revised, 1 July 2014 A term of varied application that, in its original usage, indicated a piece that preceded other music whose tonic, mode, or key it was designed to introduce; was instrumental (the roots ludus and Spiel mean ‘played’ as opposed to ‘sung’); and was improvised (hence the French préluder and the German präludieren, meaning ‘to improvise’). The term ‘praeambulum’ (preamble) adds the rhetorical function of attracting the attention of an audience and introducing a topic. The earliest notated preludes are for organ, and were used to introduce vocal music in church. Slightly later ones, for other chordal instruments such as the lute, grew out of improvisation and were a means of checking the tuning of the instrument and the quality of its tone, and of loosening the player’s fingers (as was the Tastar de corde). The purpose of notating improvisation was generally to provide models for students, so an instructive intention, often concerned with a particular aspect of instrumental technique, remained an important part of the prelude. Because improvisation may embrace a wide range of manners, styles, and techniques, the term was later applied to a variety of formal prototypes and to pieces of otherwise indeterminate genre. 1. Before 1800. David Ledbetter The oldest surviving preludes are the five short praeambula for organ in Adam Ileborgh’s tablature of 1448 (ed. -

Magdalena Kožená Anna Gourari Friedrich Gulda

www.klassikakzente.de • C 43177 • 2 • 2005 Magdalena Kožená GLUCKS VERSCHOLLENE OPER Anna Gourari DER KLANG DER WOLGA Friedrich Gulda JOACHIM KAISER, FREUND UND KRITIKER JANINE JANSEN Der Kern der „Vier Jahreszeiten“ INHALT EDITORIAL INTRO 3 Edelmetall für Anna Netrebko Heißer Herbst für Renée Fleming Andreas Kluge TITEL Foto: Kai Lerner 4 Janine Jansen: Der musikalische Kern Liebe Musikfreundin, lieber Musikfreund, MAGAZIN eigentlich könnte ich es mir leicht machen und Ihnen an dieser 8 Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau: Stelle – parallel zu Salzburg, Bayreuth, München, Luzern und Der Mann, den sie abkürzten anderswo – einfach eine neue „Opernsaison“ auf Universal 10 Sonderteil: Oper 2005 Classics ankündigen. Denn natürlich gibt’s neue Recitals, 10 Magdalena Kožená: Aufnahmen in Troja Opernquerschnitte und -gesamtaufnahmen, im CD- wie im 12 Augenschmaus: Opern-DVDs DVD-Format. Etwa Recitals mit Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, da- 14 Händel und Weber: Die Deutschen in London neben Händels „Rodelinda“, Webers „Oberon“ und Wagners 15 Riccardo Chailly: Mahler als zweite Haut „Fliegender Holländer“. Alles schon mal da gewesen, werden 16 MoMu: Mehrheitsfähige Moderne Sie denken. Aber so einfach ist die Sache nicht, denn der Teu- 18 Das andere Jubiläum: Keith Jarrett fel steckt hier im Detail. In der 9-CD-Box mit „Early Recordings“ 20 Classic Recitals: Gute alte Neuzeit des gefeierten deutschen Baritons entdeckt man nämlich bei 21 Neue ECM-Veröffentlichungen: In Kontrastwelten genauerer Untersuchung unter den 220 (sic!) Tracks dieser Ar- 22 Cristina Branco: -

KONZERTE 2013 Musikzentren Und Im Ausland

von Mozart. Es folgten Solo-Recitals in allen spanischen Elmau, Wiener Festwochen und Schleswig-Holstein Musik KONZERTE 2013 Musikzentren und im Ausland. Er erregte Aufsehen mit der Festival. Seit einigen Jahren arbeitet Florian Uhlig an einer Interpretation von Klavierkonzerten von Beethoven und Gesamtaufnahme von Robert Schumanns Klavierwerken mit 15 PIANO SOLO im Jahres-Abonnement Schumann. Bei mehreren nationalen Wettbewerben wurde CDs beim Label Hänssler Classic. Erwähnenswert ist ferner Spenden von Privatpersonen und Unternehmen ermöglichen dem Floristan jeweils mit einem ersten Preis geehrt. Der sehr sein Engagement als künstlerischer Leiter des Johannesburg Kunstverein Südsauerland die Reihe Piano Solo mit Pianisten von sympathische Pianist studiert an der Escuela Superior de International Mozart Festivals, das er seit 2008 leitet. Weltruf am Konzertflügel Steinway D des Kreises Olpe. Música Reina Sofía in Madrid und erhält wichtige Anregungen ABO- und Einzelkarten-Vorverkauf in der Volkshochschule, in Meisterkursen z. B. bei Daniel Barenboim. Als Elisabeth TILL FELLNER, WIEN Kurfürst-Heinrichstr. 34, 57462 Olpe, Tel. 02761-923 630; Fax Leonskaja 2011 mit dem Preis des Klavier-Festivals Ruhr Freitag, 11. Oktober 2013, 20 Uhr, Kreishaus Olpe 923 600; oder nach Vereinbarung per Vorabüberweisung auf das ausgezeichnet wurde, benannte sie den jungen Juan Pérez Wolfgang A. Mozart, Rondo KV 511 Konto 46888, BLZ 46250049 Sparkasse Olpe. Bestellungen per E- Floristán als ihren Stipendiaten, der sich 2012 mit einem Mail: [email protected] Joh. Seb. Bach, Wohltemp. Klavier II, Nr. 5-8 BWV 874-877 glänzenden Rezital dem Publikum vorgestellt hat. Internet: www.kunstverein-suedsauerland.de Joseph Haydn, Sonate D-Dur Hob. XVI:37 Robert Schumann, Davidsbündlertänze op. -

Guide-Mains Contexte Historique Et Enseignement Du Pianoforte Auxixe Siècle Klavierspiel Und Klavierunterricht Im 19

Guide-mains Contexte historique et enseignement du pianoforte auxixe siècle Klavierspiel und Klavierunterricht im 19. Jahrhundert Herausgegeben von Leonardo Miucci, Suzanne Perrin-Goy und Edoardo Torbianelli unter redaktioneller Mitarbeit von Daniel Allenbach und Nathalie Meidhof Edition Argus Diese PDF-Version ist seitenidentisch mit dem gedruckten Buch, das 2018 in der Edition Argus erschienen ist. Für die PDF-Version gelten dieselben Urheber- und Nutzungsrechte wie für das gedruckte Buch. Dies gilt insbesondere für Abbildungen und Notenbeispiele. Das heißt: Sie dürfen aus der PDF-Version zitieren, wenn Sie die im wissenschaftlichen Bereich üblichen Urheberangaben machen. Für die Nutzung von Abbildungen und Notenbeispielen müssen Sie gegebenenfalls die Erlaubnis der Rechteinhaber einholen. Musikforschung der Hochschule der Künste Bern Herausgegeben von Martin Skamletz und Thomas Gartmann Band 11 Guide-mains Contexte historique et enseignement du pianoforte auxixe siècle Klavierspiel und Klavierunterricht im 19. Jahrhundert Herausgegeben von Leonardo Miucci, Suzanne Perrin-Goy und Edoardo Torbianelli unter redaktioneller Mitarbeit von Daniel Allenbach und Nathalie Meidhof Inhalt Introduction 7 Vorwort 12 Pierre Goy Beethovenetleregistrequilèveles étouffoirs – innovation ou continuité? 18 Jeanne Roudet La question de l’expression au piano. Le cas exemplaire de la fantaisie libre pour clavier (1780–1850) 45 Suzanne Perrin-Goy/Alain Muller Quels doigtés pour quelle interprétation? Une analyse sémiotique des prescriptions dans les méthodes -

Johannes Brahms Konzert Für Klavier Und Orchester Nr

Johannes Brahms Konzert für Klavier und Orchester Nr. 2 Anna Malikova Duisburger Philharmoniker Jonathan Darlington Johannes Brahms Scherzo weg, das schließlich in das „Deut- Konzert für Klavier und Orchester Nr. 2 sche Requiem“ einging. B-Dur op. 83 Johannes Die beiden Klavierkonzerte von Johannes Auch die Ausarbeitung des zweiten Klavier- Brahms behaupten sich nebeneinander als konzerts nahm viel Zeit in Anspruch, doch Brahms (1833-1897) grandioses Gegensatzpaar. Die Unterschie- während beim Konzert Nr. 1 d-Moll op. 15 de beginnen sich bereits bei einem Vergleich die lange Entstehungszeit durch das Ringen Konzert für Klavier der Eingangstakte abzuzeichnen: Beginnt um die endgültige Werkgestalt begründet und Orchester Nr. 2 B-Dur op. 83 (1881) das Konzert d-Moll op. 15 noch drohend, ist, so kamen jetzt einfach andere Projekte düster und dramatisch, so hebt das Konzert dazwischen. Brahms konnte es sich nun 1 I. Allegro non troppo 19:06 B-Dur op. 83 mit einem idyllischen und na- leisten, sich mit der Ausarbeitung Zeit zu turnahen Hornsolo an. Lange hatte Johan- lassen. Die Fertigstellung des jüngeren Kla- 2 II. Allegro appassionato 9:28 nes Brahms um sein erstes Klavierkonzert vierkonzerts ging mit Gelassenheit und ohne ringen müssen. Es gehört zu denjenigen Selbstzweifel vor sich. Während die ersten 3 III. Andante – Più Adagio 12:48 Werken, mit denen der Komponist sich Aufführungen des Klavierkonzerts Nr. 1 aber 4 IV. Allegretto grazioso – Un poco più presto 9:48 den Weg zu seiner ersten Sinfonie bahnte. noch zu einem totalen Fiasko gerieten, hatte So wurde die endgültige Gestalt auch erst das zweite Klavierkonzert 1881 auf Anhieb nach vielfachem Experimentieren gefunden. -

TOC 0364 CD Booklet.Indd

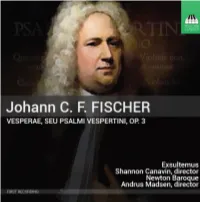

JOHANN CASPAR FERDINAND FISCHER Vesperae, seu Psalmi Vespertini, Op. 3 1 Blumen-Strauss (before 1736): Praeludium VIII 1:15 2 Domine ad adjuvandum 1:06 3 Beatus vir 3:23 4 Ariadne musica neo-organoedum (1702): Praeludium et Fuga IV 1:51 5 Conftebor 4:17 6 Ariadne musica neo-organoedum: Praeludium et Fuga XVIII 1:41 7 Credidi 2:03 8 Ariadne musica neo-organoedum: Praeludium et Fuga VIII 1:46 9 Nisi Dominus 3:28 10 Ariadne musica neo-organoedum: Praeludium et Fuga III 1:44 11 Lauda Jerusalem 5:20 12 Ariadne musica neo-organoedum: Praeludium et Fuga XVII 1:54 JOHANN CHRISTOPH PEZ Sonata in G minor 14:43 13 I Adagio 2:13 14 II Allegro 2:23 15 III Adagio 1:25 16 IV Allegro 4:21 17 V Adagio 0:41 18 VI Gigue 1:40 2 JOHANN CASPAR FERDINAND FISCHER FISCHER 19 Magnifcat 6:31 Vesperae, seu Psalmi Vespertini, Op. 3 PEZ Duplex Genius sive Gallo-Italus Instrumentorum Concentus (1696): Sonata Quinta 9:08 20 Blumen-Strauss (before 1736): Praeludium VIII 1:15 I Adagio 1:58 21 Domine ad adjuvandum 1:06 II Allegro 1:39 22 Beatus vir 3:23 III Adagio 3:03 23 Ariadne musica neo-organoedum (1702): Praeludium et Fuga IV 1:51 IV Vivace 1:28 Conftebor 4:17 FISCHER Ariadne musica neo-organoedum: Praeludium et Fuga XVIII 1:41 24 Lytaniae Lauretanae VII (1711): Salve Regina 5:27 Credidi 2:03 TT 63:35 Ariadne musica neo-organoedum: Praeludium et Fuga VIII 1:46 Nisi Dominus 3:28 Exsultemus Ariadne musica neo-organoedum: Praeludium et Fuga III 1:44 Shannon Canavin and Margot Rood, sopranos Lauda Jerusalem 5:20 Thea Lobo and Gerrod Pagenkopf, altos Ariadne musica neo-organoedum: -

Web Feature 17.1 1

Kevin Holm-Hudson Music Theory Remixed, Web Feature 17.1 1 Web Feature 17.1 Tonality as a journey The idea of key relationships in music as “distances” to be traveled goes back at least as far as the eighteenth century; in 1702 the composer J. K. F. Fischer published a collection of pieces in nineteen different keys (plus the Phrygian mode) entitled Ariadne musica. The work’s title is a reference to Ariadne’s ball of thread that guided Theseus through the labyrinth in Greek mythology; thus, this was a set of pieces that systematically and collectively explored the relationships among the different keys and “guided” the performer among them. Similarly, J. S. Bach’s son Carl Phillipp Emanuel Bach (1714– 1788) described in his influential book, Essay on the True Art of Playing Keyboard Instruments (1762), how a performer might negotiate a dramatic path among keys that had different perceived “distances” from one another: “in a free fantasia modulation may be made to closely related, remote, and all other keys.”1 He also points out: “It is one of the beauties of improvisation to feign modulation to a new key through a formal cadence and then move off in another direction. This and other rational deceptions make a fantasia attractive.”2 All the same, he cautions the performer to use restraint in structuring the improvisation in a manner that would befit a narrative, not veering off into the “adventure” at the beginning or returning “home” at the end too early: When only little time is available for the display of craftsmanship, the performer should not wander into too remote keys, for the performance must soon come to an end. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Negishi, Yuki (2018). Haptic influences on Chopin pianism: case studies from the music of Szymanowska and Kessler. (Unpublished Masters thesis, Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/22012/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] Haptic Influences on Chopin Pianism: Case Studies from the music of Szymanowska and Kessler Submitted for the Degree of Master of Philosophy at Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance for Creative Practice, Music December 2018 Yuki Negishi 1 Table of Contents • Introduction- The meaning of ‘haptic’….………………………………………………………..P.6 • Chapter 1 ◦ Historiographical Framework………………………………………………………………………P.7 -

COMPLETE PRELUDES Alexandra Dariescu FOREWORD

Vol . 1 COMPLETE PRELUDES Alexandra Dariescu FOREWORD I am delighted to present the first disc of a ‘Trilogy of Preludes’ containing the complete works of this genre of Frédéric Chopin and Henri Dutilleux. Capturing a musical genre from its conception to today has been an incredibly exciting journey. Chopin was the first composer to write preludes that are not what the title might suggest – introduction to other pieces – but an art form in their own right. Chopin’s set was the one to inspire generations and has influenced composers to the present day. Dutilleux’s use of polyphony, keyboard layout and harmony echoes Chopin as he too creates beauty though on a different level through his many colours and shaping of resonances. Recording the complete preludes of these two composers was an emotional roller coaster as each prelude has a different story to tell and as a whole, they go through every single emotion a human can possibly feel. Champs Hill Music Room provided the most wonderful forum for creating all of these moods. I am extremely grateful to our producer Matthew Bennett and sound engineer Dave Rowell, who were not only a fantastic team to work with but also an incredible source of information and inspiration. I would also like to express my sincere gratitude to Mary and David Bowerman and the entire team at Champs Hill for believing in me and making this project happen. Heartfelt thanks to photographer Vladimir Molico who captured the atmosphere Chopin found during the rainy winter of 1838 in Majorca through a modern adaptation of Renoir's Les Parapluies . -

J.S. Bach - Well-Tempered Clavier 1

J.S. BACH - WELL-TEMPERED CLAVIER 1 For more than two centuries Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier has had a distinct status in our musical cultural heritage. No other composition has been so prevalent in reaching the performing musician, listener, theoretician and composer, even outranking the Goldberg Variations and the Inventions and Sinfonias. The Well-Tempered Clavier has virtually never been absent from the podium or the music room. Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin, Mendelssohn, Liszt, Bruckner and Brahms were all intimately familiar with this music! Not only the repeated set combination of a prelude and fugue, but also the added fact that Bach moves step by step through all the twelve major and minor keys, and does not for one moment give the impression, that it is an ingenious study piece of the composer or for the performing musician: the Well-Tempered Clavier has provided a function as an outstanding example. “Das Wohltemperirte Clavier. oder Praeludia, und Fugen durch alle Tone und Semitonia, So wohl tertiam majoram oder Ut Re Mi anlan- gend, als auch tertiam minorem oder Re Mi Fa betreffend. Zum Nutzen und Gebrauch der Lehr-begierigen Musicalischen Jugend, als auch dere in diesem stu- dio schon habil seyenden besonderem ZeitVertreib auffgesetzet und verfertigt von Johann Sebastian Bach. p.t.: HochFürstlich Anhalt- Cöthenschen Capel- Meistern und Di- rectore derer Cammer Mu- siquen. Anno 1722" Although the title page of the first book of the Well-Tempered Clavier – a similar second book would appear later – indicates the year 1722, after Bach’s death a story did the rounds for a long time that he had written the whole volume out of sheer boredom because of the lack of a clavier (in Weimar or Carlsbad). -

GERMAN ORGAN MUSIC Volume 1 Fischer Praetorius Bohm Scheidemann and Others Joseph Payne, Organ GERMAN ORGAN MUSIC VOLUME 1

8.550964 GERMAN ORGAN MUSIC Volume 1 Fischer Praetorius Bohm Scheidemann and others Joseph Payne, Organ GERMAN ORGAN MUSIC VOLUME 1 Organ music of the German-speaking countries is vast and varied, and more than anywhere else in Europe, it reached considerable complexity by the early 15th century. This repertory reflects the complex development of large, fixed organs, about which few generalizations can be made, as well as the more uniform evolution of smaller forms of organs. Among these was the portative, a small portable organ blown by a pair of bellows operated by one of the player's hands. Capable of performing only one part, this was a "monophonic" instrument used mainly in ensembles with other instruments and singers in the performance of polyphonic music. Somewhat larger and more or less stationary was the positive. It employed bellows that were operated by a second person, enabling the organist to use both hands so that several notes might be played simultaneously on a chromatic keyboard. Both these smaller types of organ employed flue pipes, while reed pipes were used in a third type, the regal. (There are many depictions of these small organs; a famous one can be found on the altar painting by Jan van Eyck at St. Bavo in Ghent). Towards the end of the Middle Ages, many tonal and mechanical features of the smaller organs were incorporated into the resources of the full-sized church Orgelwerk. This was a decisive step towards the modern organ: the organ came to be regarded as a composite of several instruments of various capabilities and functions, its resources controlled from several different keyboards. -

Rodion Shchedrin

RODION SHCHEDRIN VERZEICHNIS DER BEI SCHOTT VERÖFFENTLICHTEN WERKE LIST OF WORKS PUBLISHED BY SCHOTT Stand Juli 2017 up to July 2017 Mainz · London · Berlin · Madrid · New York · Paris · Prague · Tokyo · Toronto Die Aufführungsmateriale zu den Bühnen-, Orchester- und Chorwerken dieses Verzeichnisses stehen leihweise nach Vereinbarung zur Verfügung, sofern nicht anders angegeben. Bitte richten Sie Ihre Bestellung per E-Mail an [email protected] oder an den für Ihr Liefergebiet zuständigen Vertreter bzw. die zuständige Schott-Niederlassung. Alle Ausgaben mit Bestellnummern erhalten Sie im Musikalienhandel und über unseren Online-Shop, teilweise auch zum Download auf www.notafina.com. Kostenloses Informationsmaterial zu allen Werken können Sie per E-Mail an [email protected] anfor - dern. Dieser Katalog wurde im Juli 2017 abgeschlossen. Alle Zeitangaben sind approximativ. The performance materials of the stage, orchestral and choral works of this catalogue are available on hire upon request, unless otherwise stated. Please send your e-mail order to [email protected] or to the agent responsible for your territory of delivery or to the competent Schott branch. All editions with edition numbers are available from music shops and via our online shop, some of them also for download on www.notafina.com. Free info material on all works can be requested by e-mail at infoservice@schott- music.com. This catalogue was completed in July 2017. All durations are approximate. Titelfoto / Cover photo: Schott-Archiv / Milan Wagner Schott Music GmbH & Co. KG · Mainz Weihergarten 5, 55116 Mainz/Germany, Postfach 3640, 55026 Mainz/Germany Geschäftszeit: Montag bis Donnerstag von 8:30 bis 12:30 und 13:30 bis 17:00 Uhr Freitag von 8:30 bis 12:30 und 13:30 bis 16:00 Uhr Tel +49 6131 246-0, Fax +49 6131 246-211 [email protected] · www.schott-music.com Schott Music Ltd.