Prelude | Grove Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

0 – Inleiding – Drie Bedenkingen

0 – INLEIDING – DRIE BEDENKINGEN Bedenking 1 ‘Klassieke muziek’ is een wijd verbreid begrip. Toch is het een beetje een ongelukkige benaming. Het gaat om meer dan muziek uit de classicistische tijd – de tweede helft van de 18de eeuw. Mogelijk een betere omschrijving is: Europese (westerse) ‘kunstmuziek’, waarvan de geschiedenis een periode van ongeveer 1000 jaar omspant. Deze westerse ‘kunstmuziek’ onderscheidt zich: 1) van populaire muziek (volksmuziek – ‘wereld’muziek – jazz – pop – …), 2) van kunstmuziek uit andere culturen door: gecomponeerde en dus genoteerde meerstemmigheid Bedenking 2 De plaats die muziek in onze eigentijdse samenleving inneemt, is – vergeleken met het verleden – nieuw en bijzonder. Deze breuk met het verleden, die zich kort na 1900 begon af te tekenen onder invloed van allerlei technologische en maatschappelijke veranderingen, kunnen we ons als volgt voorstellen: de ste tot en met de 19 eeuw vanaf de 20 eeuw alle muziek is live muziek is eindeloos reproduceerbaar, waardoor live-uitvoeringen zwaar onder druk komen te staan ( zijn ze wel nodig? + al te kritische benadering ) beperkt aanbod onbeperkt aanbod het overgrote deel van de muziek is de gehoorde muziek is vaak niet eigen- eigentijds en is dus een directe tijds, waardoor een eigentijds klankbeeld uitdrukking van de tijdsgeest veel minder eenduidig wordt de gehoorde muziek past in de eigen muziek kan uit alle leefruimtes komen, leefruimte, zowel geografisch als zowel geografisch als naar stand en naar stand en geloof geloof - wat met het echte begrip? pas -

The Lute Society Microfilm Catalogue Version 2 12/13 the List Is Divided by Instrument. Works for Renaissance Lute with Voice A

The Lute Society Microfilm Catalogue Version 2 12/13 The list is divided by instrument. Works for Renaissance lute with voice and in ensemble are separated because of the size of the main list. The categories are: Renaissance lute Renaissance lute with voice Renaissance lute in ensemble (with other instruments) Lute in transitional tunings (accords nouveaux) Vihuela Baroque lute Renaissance guitar Baroque guitar Bandora Cittern Mandore Orpharion Theorbo Musical scores without plucked instrument tablature Theoretical works without music The 'Other instruments' column shows where there is music in the work for other listed instruments. The work also appears in the other list(s) for ease of reference. The list is sorted by composer or compiler, where known. Anonymous manuscripts are listed at the end of each section, sorted by shelf mark. Date references are to HM Brown Instrumental Music printed before 1600. Where the date is asterisked the work is not in Brown. Tablature style is shown as French (F), German (G), Italian (I), Inverted Italian (II) or Keyboard (K) The Collection and MCN fields identify each reel and the collection to which it belongs. Renaissance Lute Other Composer/ Compiler Title Shelf Mark or HMB Tab Format Coll MCN Duplicates Notes Instrument(s) Intabolatura di Julio Abondante Sopra el Julio Abondante 1546 I Print MP 59 Lauto Libro Primo 1 Julio Abondante Intabolatura di Lauto Libro Secondo 15481 I Print MP 60 GC 195 Intabolatura di liuto . , novamente Julio Abondante ristampati, Libro primo 15631 I Print MP 62 GC 194, -

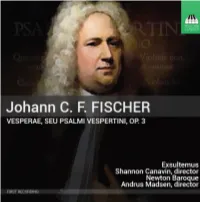

TOC 0364 CD Booklet.Indd

JOHANN CASPAR FERDINAND FISCHER Vesperae, seu Psalmi Vespertini, Op. 3 1 Blumen-Strauss (before 1736): Praeludium VIII 1:15 2 Domine ad adjuvandum 1:06 3 Beatus vir 3:23 4 Ariadne musica neo-organoedum (1702): Praeludium et Fuga IV 1:51 5 Conftebor 4:17 6 Ariadne musica neo-organoedum: Praeludium et Fuga XVIII 1:41 7 Credidi 2:03 8 Ariadne musica neo-organoedum: Praeludium et Fuga VIII 1:46 9 Nisi Dominus 3:28 10 Ariadne musica neo-organoedum: Praeludium et Fuga III 1:44 11 Lauda Jerusalem 5:20 12 Ariadne musica neo-organoedum: Praeludium et Fuga XVII 1:54 JOHANN CHRISTOPH PEZ Sonata in G minor 14:43 13 I Adagio 2:13 14 II Allegro 2:23 15 III Adagio 1:25 16 IV Allegro 4:21 17 V Adagio 0:41 18 VI Gigue 1:40 2 JOHANN CASPAR FERDINAND FISCHER FISCHER 19 Magnifcat 6:31 Vesperae, seu Psalmi Vespertini, Op. 3 PEZ Duplex Genius sive Gallo-Italus Instrumentorum Concentus (1696): Sonata Quinta 9:08 20 Blumen-Strauss (before 1736): Praeludium VIII 1:15 I Adagio 1:58 21 Domine ad adjuvandum 1:06 II Allegro 1:39 22 Beatus vir 3:23 III Adagio 3:03 23 Ariadne musica neo-organoedum (1702): Praeludium et Fuga IV 1:51 IV Vivace 1:28 Conftebor 4:17 FISCHER Ariadne musica neo-organoedum: Praeludium et Fuga XVIII 1:41 24 Lytaniae Lauretanae VII (1711): Salve Regina 5:27 Credidi 2:03 TT 63:35 Ariadne musica neo-organoedum: Praeludium et Fuga VIII 1:46 Nisi Dominus 3:28 Exsultemus Ariadne musica neo-organoedum: Praeludium et Fuga III 1:44 Shannon Canavin and Margot Rood, sopranos Lauda Jerusalem 5:20 Thea Lobo and Gerrod Pagenkopf, altos Ariadne musica neo-organoedum: -

Web Feature 17.1 1

Kevin Holm-Hudson Music Theory Remixed, Web Feature 17.1 1 Web Feature 17.1 Tonality as a journey The idea of key relationships in music as “distances” to be traveled goes back at least as far as the eighteenth century; in 1702 the composer J. K. F. Fischer published a collection of pieces in nineteen different keys (plus the Phrygian mode) entitled Ariadne musica. The work’s title is a reference to Ariadne’s ball of thread that guided Theseus through the labyrinth in Greek mythology; thus, this was a set of pieces that systematically and collectively explored the relationships among the different keys and “guided” the performer among them. Similarly, J. S. Bach’s son Carl Phillipp Emanuel Bach (1714– 1788) described in his influential book, Essay on the True Art of Playing Keyboard Instruments (1762), how a performer might negotiate a dramatic path among keys that had different perceived “distances” from one another: “in a free fantasia modulation may be made to closely related, remote, and all other keys.”1 He also points out: “It is one of the beauties of improvisation to feign modulation to a new key through a formal cadence and then move off in another direction. This and other rational deceptions make a fantasia attractive.”2 All the same, he cautions the performer to use restraint in structuring the improvisation in a manner that would befit a narrative, not veering off into the “adventure” at the beginning or returning “home” at the end too early: When only little time is available for the display of craftsmanship, the performer should not wander into too remote keys, for the performance must soon come to an end. -

Copyright by Gary Dean Beckman 2007

Copyright by Gary Dean Beckman 2007 The Dissertation Committee for Gary Dean Beckman Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Sacred Lute: Intabulated Chorales from Luther’s Age to the beginnings of Pietism Committee: ____________________________________ Andrew Dell’ Antonio, Supervisor ____________________________________ Susan Jackson ____________________________________ Rebecca Baltzer ____________________________________ Elliot Antokoletz ____________________________________ Susan R. Boettcher The Sacred Lute: Intabulated Chorales from Luther’s Age to the beginnings of Pietism by Gary Dean Beckman, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2007 Acknowledgments I would like to acknowledge Dr. Douglas Dempster, interim Dean, College of Fine Arts, Dr. David Hunter, Fine Arts Music Librarian and Dr. Richard Cherwitz, Professor, Department of Communication Studies Coordinator from The University of Texas at Austin for their help in completing this work. Emeritus Professor, Dr. Keith Polk from the University of New Hampshire, who mentored me during my master’s studies, deserves a special acknowledgement for his belief in my capabilities. Olav Chris Henriksen receives my deepest gratitude for his kindness and generosity during my Boston lute studies; his quite enthusiasm for the lute and its repertoire ignited my interest in German lute music. My sincere and deepest thanks are extended to the members of my dissertation committee. Drs. Rebecca Baltzer, Susan Boettcher and Elliot Antokoletz offered critical assistance with this effort. All three have shaped the way I view music. -

Shakespeare 400 Music, Songs and Poetry from the Renaissance - the Cultural Bridge Between the Middle Ages and Modern History in Europe

13thInternational Music Festival Phnom Penh 3-7 November 2016 Shakespeare 400 Music, songs and poetry from the Renaissance - the cultural bridge between the Middle Ages and modern history in Europe European Union International Music Festival Phnom Penh www.musicfestival-phnompenh.org Contact 077 787038 / 015755718 / [email protected] Dear Music Lovers This year, I am pleased to invite you to explore European Renais- sance Music. The central inspirational figure - William Shakespeare - indeed influenced Drama and Music. His stage directions call for music more than 300 times, and his plays are full of beautiful tributes to music. The Festival will mark the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death in 1616. The Renaissance in music occurred between 1450 and 1625, including the transitional period from Renaissance to Early Baroque. As in the other arts, the horizons of music were greatly expanded. The circulation of music and the number of composers and performers increased. The humanistic interest in language (Shakespeare and his contemporaries) influenced vocal music, creating a close relationship between words and music. Renais- sance composers wrote music to enhance the meaning and emotion of the text. The festival program is a snapshot of the musical life during the European Renaissance and leads us to refined musical forms, such as the opera during the end of the period. In six concerts, you will experience selected songs, poetry and pure instrumental forms. These performing practices took place mostly in domestic interiors in a private sphere of all milieu of society. I look forward to welcome again international artists, with their luggage of historical Instruments including a Spinet, Lute, and Viola da Gamba, to perform music from: England, France, The Nether- lands, Belgium, Germany, Italy and Spain I warmly invite all music lovers, young and old and also those new to classical music to take full advantage of the feast of music offered by this year’s concert program of European Renaissance music. -

J.S. Bach - Well-Tempered Clavier 1

J.S. BACH - WELL-TEMPERED CLAVIER 1 For more than two centuries Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier has had a distinct status in our musical cultural heritage. No other composition has been so prevalent in reaching the performing musician, listener, theoretician and composer, even outranking the Goldberg Variations and the Inventions and Sinfonias. The Well-Tempered Clavier has virtually never been absent from the podium or the music room. Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin, Mendelssohn, Liszt, Bruckner and Brahms were all intimately familiar with this music! Not only the repeated set combination of a prelude and fugue, but also the added fact that Bach moves step by step through all the twelve major and minor keys, and does not for one moment give the impression, that it is an ingenious study piece of the composer or for the performing musician: the Well-Tempered Clavier has provided a function as an outstanding example. “Das Wohltemperirte Clavier. oder Praeludia, und Fugen durch alle Tone und Semitonia, So wohl tertiam majoram oder Ut Re Mi anlan- gend, als auch tertiam minorem oder Re Mi Fa betreffend. Zum Nutzen und Gebrauch der Lehr-begierigen Musicalischen Jugend, als auch dere in diesem stu- dio schon habil seyenden besonderem ZeitVertreib auffgesetzet und verfertigt von Johann Sebastian Bach. p.t.: HochFürstlich Anhalt- Cöthenschen Capel- Meistern und Di- rectore derer Cammer Mu- siquen. Anno 1722" Although the title page of the first book of the Well-Tempered Clavier – a similar second book would appear later – indicates the year 1722, after Bach’s death a story did the rounds for a long time that he had written the whole volume out of sheer boredom because of the lack of a clavier (in Weimar or Carlsbad). -

GERMAN ORGAN MUSIC Volume 1 Fischer Praetorius Bohm Scheidemann and Others Joseph Payne, Organ GERMAN ORGAN MUSIC VOLUME 1

8.550964 GERMAN ORGAN MUSIC Volume 1 Fischer Praetorius Bohm Scheidemann and others Joseph Payne, Organ GERMAN ORGAN MUSIC VOLUME 1 Organ music of the German-speaking countries is vast and varied, and more than anywhere else in Europe, it reached considerable complexity by the early 15th century. This repertory reflects the complex development of large, fixed organs, about which few generalizations can be made, as well as the more uniform evolution of smaller forms of organs. Among these was the portative, a small portable organ blown by a pair of bellows operated by one of the player's hands. Capable of performing only one part, this was a "monophonic" instrument used mainly in ensembles with other instruments and singers in the performance of polyphonic music. Somewhat larger and more or less stationary was the positive. It employed bellows that were operated by a second person, enabling the organist to use both hands so that several notes might be played simultaneously on a chromatic keyboard. Both these smaller types of organ employed flue pipes, while reed pipes were used in a third type, the regal. (There are many depictions of these small organs; a famous one can be found on the altar painting by Jan van Eyck at St. Bavo in Ghent). Towards the end of the Middle Ages, many tonal and mechanical features of the smaller organs were incorporated into the resources of the full-sized church Orgelwerk. This was a decisive step towards the modern organ: the organ came to be regarded as a composite of several instruments of various capabilities and functions, its resources controlled from several different keyboards. -

Bach Notes 29

No. 29 Fall 2018 BACH NOTES NEWSLETTER OF THE AMERICAN BACH SOCIETY BACHFEST LEIPZIG 2018: CYCLES A CONFERENCE REPORT BY YO TOMITA achfest Leipzig listening experience. B2018 took place There was an immensely from June 8–17 with warm and appreciative at- the theme “Zyklen” mosphere in the acoustic (Cycles), featuring space once owned and ex- works that can be ploited to its full by Bach grouped together, for himself almost 300 years instance collections ago. To me this part of the of six or twenty-four Bachfest was a resound- pieces, numbers with ing success. It will be long potential biblical sig- remembered, especially by nificance, or works the fully packed exuberant that share formal or audience at the tenth and stylistic features. In the final concert of the addition, this year’s Kantaten-Ring on June festival presented 10 in the Nikolaikirche, something quite ex- where the Monteverdi traordinary: nearly all Choir and English Ba- the main slots in the John Eliot Gardiner in the Nikolaikirche (Photo Credit: Leipzig Bach Festival/Gert Mothes) roque Soloists directed by first weekend (June 8–10) were filled by a vocal works from the sixteenth and seven- series of concerts called “Leipziger Kantat- teenth centuries. This arrangement exposed en-Ring” (Leipzig Ring of Cantatas), which the stylistic differences between Bach and In This Issue: looked like a festival of Bach cantatas within his predecessors, prompting us to consider the Bachfest. (Its own program book, at why and how Bach’s musical style might Conference Report: Bachfest Leipzig . 1 351 pages, was three times thicker than the have evolved, a precious moment to reflect entire booklet of the Bachfest!) Altogether on Bach’s ingenuity. -

The Sources and the Performing Traditions. Alexander Agricola: Musik Zwischen Vokalität Und Instrumentalismus, Ed

Edwards, W. (2006) Agricola's songs without words: the sources and the performing traditions. Alexander Agricola: Musik zwischen Vokalität und Instrumentalismus, ed. Nicole Schwindt, Trossinger Jahrbuch für Renaissancemusik 6:pp. 83-121. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/4576/ 21th October 2008 Glasgow ePrints Service https://eprints.gla.ac.uk Warwick Edwards Agricola’s Songs Without Words The Sources and the Performing Traditions* In 1538 the Nuremberg printer Hieronymus Formschneider issued a set of part- books entitled Trium vocum carmina1 and containing a retrospective collection of one hundred untexted and unattributed three-voice compositions, six of which can be assigned to Agricola. Whoever selected them and commissioned the publication added a preface (transcribed, with English translation in Appendix pp. 33–4) that offers – most unusually for the time – a specific explanation for leaving out all the words. This turns out to have nothing to do with performance, let alone the possible use of instruments, which are neither ruled in nor ruled out. Nor does it express any worries about readers’ appetites for texts in foreign languages, or mention that some texts probably never existed in the first place. Instead, the author pleads, rather surprisingly, that the appearance of the books would have been spoilt had words variously in German, French, Italian and Latin been mixed in together. Moreover, the preface continues, the composers of the songs had regard for erudite sonorities rather than words. The learned musician, then, will enjoy the -

Liederbuch Dancing Through the Songbooks of Renaissance Germany

Early Music Hawaii presents Liederbuch Dancing Through the Songbooks of Renaissance Germany Ciaramella Adam Gilbert, shawm, recorder, bagpipe, dulcian Rotem Gilbert, shawm, recorder, bagpipe Malachai Komanoff Bandy, shawm, viol, hurdy-gurdy, bagpipe Aki Nishiguchi, shawm, recorder, cornamuse Jason Yoshida, vihuela, guitar, percussion Saturday, March 10, 2018, 7:30 pm Lutheran Church of Honolulu Sunday, March 11, 2018, 2:00 pm Lutheran Church of the Holy Trinity, Kailua-Kona This concert is supported in part with funds provided by the Western States Arts Foundation (WESTAF), the Hawaii State Foundation on Culture and the Arts and the Program Branles double Michael Praetorius (1571-1621) Gavottes Praetorius Maria salve virginum Conradus Rupsch der Singer (c.1475-1530) Hymnizemus regi altissimo Rupsch? Annavasanna Conrad Paumann (c.1410-1473) Mater sancta dulcis Anna Anon. German (c.1500) Mit ganczem willen Paumann Mein traut geselle Anon. German (c.1500) Zart Lieb Anon. German (c.1500) Ach Elslein, liebes Elslein mein Ludwig Senfl (1486-1542) In Gottes Namen fahren wir Paul Hofhaimer (1459-1537) In Gottes Namen fahren wir Heinrich Finck (1445-1527) Nigra sum sed formosa Finck Ach liebe Herr Adam Gilbert, over 15th c. Melody Ach reine zart Anonymous In feurs hitz Anonymous Le petit Rouen Gilbert, over 15th c. Tenor Intermission Dance suite from Danserye Tielman Susato (c.1510-after 1570) Ronde IV, Ronde VI/Salterelle, Ronde IX Preambel Hans Neusidler (c.1508-1563) Variations over “Wil nieman singen” Melody after Ludwig Senfl (1486-1542) Variations over “Mein junges Leben hat ein Ende” Gilbert Variations over Praetorius’ Pavane d’Espagne Gilbert Canarios Gaspar Sanz (1640-1710) Volte Praetorius 2 Ciaramella Praised for performing 15th century counterpoint “with the ease of jazz musicians improvising on a theme,” Ciaramella brings to life medieval and early renaissance music from historical events and manuscripts. -

Davitt Moroney, Harpsichord 14

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS PROGRAM A Saturday, October 24, 2009, 8pm Hertz Hall 13. Prelude and Fugue in F-sharp major, bwv 858 Davitt Moroney, harpsichord 14. Prelude and Fugue in F-sharp minor, bwv 859 harpsichord by John Phillips (Berkeley, 1995), 15. Prelude and Fugue in G major, bwv 860 after the historical instrument in the Musée instrumental, Citée de la Musique, Paris, 16. Prelude and Fugue in G minor, bwv 861 built by Andreas Ruckers (Antwerp, 1646), rebuilt by François-Étienne Blanchet (Paris, 1756) and Pascal Taskin (Paris, 1780) 17. Prelude and Fugue in A-flat major, bwv 862 18. Prelude and Fugue in G-sharp minor, bwv 863 19. Prelude and Fugue in A major, bwv 864 20. Prelude and Fugue in A minor, bwv 865 PROGRAM 21. Prelude and Fugue in B-flat major,bwv 866 22. Prelude and Fugue in B-flat minor,bwv 867 Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) 23. Prelude and Fugue in B major, bwv 868 24. Prelude and Fugue in B minor, bwv 869 Das Wolhtemperirte Clavier (“The Well-Tempered Clavier”), bwv 846–893 Book 1 (1722) Cal Performances’ 2009–2010 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. 1. Prelude and Fugue in C major, bwv 846 2. Prelude and Fugue in C minor, bwv 847 3. Prelude and Fugue in C-sharp major, bwv 848 4. Prelude and Fugue in C-sharp minor, bwv 849 5. Prelude and Fugue in D major, bwv 850 6. Prelude and Fugue in D minor, bwv 851 Sightlines 7. Prelude and Fugue in E-flat major,bwv 852 8.