J.S. Bach - Well-Tempered Clavier 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bach: Goldberg Variations

The Choir of King’s College, Cambridge Final Logo Brand Extension Logo 06.27.12 BACH GOLDBERG VARIATIONS Parker Ramsay | harp PARKER RAMSAY Parker Ramsay was the first American to hold the post of Organ Scholar at King’s, from 2010–2013, following a long line of prestigious predecessors. Organ Scholars at King’s are undergraduate students at the College with a range of roles and responsibilities, including playing for choral services in the Chapel, assisting in the training of the probationers and Choristers, and conducting the full choir from time to time. The position of Organ Scholar is held for the duration of the student’s degree course. This is Parker’s first solo harp recording, and the second recording by an Organ Scholar on the College’s own label. 2 BACH GOLDBERG VARIATIONS Parker Ramsay harp 3 CD 78:45 1 Aria 3:23 2 Variatio 1 1:57 3 Variatio 2 1:54 4 Variatio 3 Canone all’Unisono 2:38 5 Variatio 4 1:15 6 Variatio 5 1:43 7 Variatio 6 Canone alla Seconda 1:26 8 Variatio 7 al tempo di Giga 2:24 9 Variatio 8 2:01 10 Variatio 9 Canone alla Terza 1:49 11 Variatio 10 Fughetta 1:45 12 Variatio 11 2:22 13 Variatio 12 Canone alla Quarta in moto contrario 3:21 14 Variatio 13 4:36 15 Variatio 14 2:07 16 Variatio 15 Canone alla Quinta. Andante 3:24 17 Variatio 16 Ouverture 3:26 18 Variatio 17 2:23 19 Variatio 18 Canone alla Sesta 1:58 20 Variatio 19 1:45 21 Variatio 20 3:10 22 Variatio 21 Canone alla Settima 2:31 23 Variatio 22 alla breve 1:42 24 Variatio 23 2:33 25 Variatio 24 Canone all’Ottava 2:30 26 Variatio 25 Adagio 4:31 27 Variatio 26 2:07 28 Variatio 27 Canone alla Nona 2:18 29 Variatio 28 2:29 30 Variatio 29 2:04 31 Variatio 30 Quodlibet 2:38 32 Aria da Capo 2:35 4 AN INTRODUCTION analysis than usual. -

Prelude | Grove Music

Prelude (Fr. prélude; Ger. Vorspiel; It., Sp. preludio; Lat. praeludium, praeambulum) David Ledbetter and Howard Ferguson https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.43302 Published in print: 20 January 2001 Published online: 2001 updated and revised, 1 July 2014 A term of varied application that, in its original usage, indicated a piece that preceded other music whose tonic, mode, or key it was designed to introduce; was instrumental (the roots ludus and Spiel mean ‘played’ as opposed to ‘sung’); and was improvised (hence the French préluder and the German präludieren, meaning ‘to improvise’). The term ‘praeambulum’ (preamble) adds the rhetorical function of attracting the attention of an audience and introducing a topic. The earliest notated preludes are for organ, and were used to introduce vocal music in church. Slightly later ones, for other chordal instruments such as the lute, grew out of improvisation and were a means of checking the tuning of the instrument and the quality of its tone, and of loosening the player’s fingers (as was the Tastar de corde). The purpose of notating improvisation was generally to provide models for students, so an instructive intention, often concerned with a particular aspect of instrumental technique, remained an important part of the prelude. Because improvisation may embrace a wide range of manners, styles, and techniques, the term was later applied to a variety of formal prototypes and to pieces of otherwise indeterminate genre. 1. Before 1800. David Ledbetter The oldest surviving preludes are the five short praeambula for organ in Adam Ileborgh’s tablature of 1448 (ed. -

Simone Dinnerstein, Piano Sat, Jan 30 Virtual Performance Simone Dinnerstein Piano

SIMONE DINNERSTEIN, PIANO SAT, JAN 30 VIRTUAL PERFORMANCE SIMONE DINNERSTEIN PIANO SAT, JAN 30 VIRTUAL PERFORMANCE PROGRAM Ich Ruf Zu Dir Frederico Busoni (1866-1924) Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Three Chorales Johann Sebastian Bach Ich Ruf Zu Dir Richard Danielpour Frederico Busoni (1866-1924) | Johann Sebastian Bach, (1685-1750) (b, 1956) Les Barricades Mysterieuses François Couperin (1688-1733) Arabesque in C major, Op. 18 Robert Schumann (1810-1856) Mad Rush Philip Glass (b. 1937) Tic Toc Choc François Couperin BACH: “ICH RUF’ ZU DIR,” BWV 639 (ARR. BUSONI) Relatively early in his career, Bach worked in Weimar as the court organist. While serving in this capacity, he produced his Orgelbüchlein (little organ book): a collection of 46 chorale preludes. Each piece borrows a Lutheran hymn tune, set in long notes against a freer backdrop. “Ich ruf’ zu dir,” a general prayer for God’s grace, takes a particularly plaintive approach. The melody is presented with light ornamentation in the right hand, a flowing middle voice is carried by the left, and the organ’s pedals offer a steady walking bassline. The work is further colored by Bach’s uncommon choice of key, F Minor, which he tended to reserve for more wrought contrapuntal works. In this context, though, it lends a warmth to the original text’s supplication. In arranging the work for piano, around the year 1900, Busoni’s main challenge was to condense the original three-limbed texture to two. Not only did he manage to do this, while preserving the original pitches almost exactly, he found a way to imitate the organ’s timbral fullness. -

Bach and Money: Sources of Salary and Supplemental Income in Leipzig from 1723 to 1750*

Understanding Bach, 12, 111–125 © Bach Network UK 2017 Young Scholars’ Forum Bach and Money: Sources of Salary and Supplemental Income in Leipzig * from 1723 to 1750 NOELLE HEBER It was his post as Music Director and Cantor at the Thomasschule that primarily marked Johann Sebastian Bach’s twenty-seven years in Leipzig. The tension around the unstable income of this occupation drove Bach to write his famous letter to Georg Erdmann in 1730, in which he expressed a desire to seek employment elsewhere.1 The difference between his base salary of 100 Thaler and his estimated total income of 700 Thaler was derived from legacies and foundations, funerals, weddings, and instrumental maintenance in the churches, although many payment amounts fluctuated, depending on certain factors such as the number of funerals that occurred each year. Despite his ongoing frustration at this financial instability, it seems that Bach never attempted to leave Leipzig. There are many speculations concerning his motivation to stay, but one could also ask if there was a financial draw to settling in Leipzig, considering his active pursuit of independent work, which included organ inspections, guest performances, private music lessons, publication of his compositions, instrumental rentals and sales, and, from 1729 to 1741, direction of the collegium musicum. This article provides a new and detailed survey of these sources of revenue, beginning with the supplemental income that augmented his salary and continuing with his freelance work. This exploration will further show that Leipzig seems to have been a strategic location for Bach to pursue and expand his independent work. -

Goldberg Variations

J. S. Bach Goldberg-Variationen BWV 988 1 ARIA mit verschiedenen Veränderungen für Cembalo mit 2 Manualen (Goldberg-Variationen) BWV 988 3 4 43 5 9 13 To our lovely children, from Mom and Dad. Thank you for all of the joy you have brought to our lives. 2 17 20 23 27 30 3 VARIATIO 1 a 1 Clav. 3 4 3 4 4 7 10 13 Für Natalie, Fiona und Isabelle. 'Dem höchsten Gott allein zu Ehren, dem Nächsten, draus sich zu belehren' - 4 Lebensmusik, im Sinne des Meisters nun freigesetzt, für Euch und Eure Welt. 17 20 23 26 -

Goldberg Variations' in the Neue Bach Ausgabe Erich Schwandt

Performance Practice Review Volume 3 Article 2 Number 1 Spring Questions concerning the Edition of the 'Goldberg Variations' in the Neue Bach Ausgabe Erich Schwandt Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Schwandt, Erich (1990) "Questions concerning the Edition of the 'Goldberg Variations' in the Neue Bach Ausgabe," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 3: No. 1, Article 2. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199003.01.2 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol3/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Editing Problems Questions Concerning the Edition of the 'Goldberg Variations* in the Neue Bach Ausgabe Erich Schwandt The world has been waiting for almost 250 years for a completely authoritative text of the "Goldberg Variations," which were published in Bach's lifetime (in 1741 or 1742) as the fourth part of the Clavierilbung. Balthasar Schmid of Nuremburg engraved them with great care; nonetheless, his elegant engraving contained a few wrong notes, and some slurs, ties, accidentals, and ornament signs were inadvertently omitted. In addition, some of the ornaments are ambiguous, and some blurred. In the absence of Bach's autograph, Schmid's engraving must remain the primary source for the "Goldberg Variations," and Bach's own 'corrected' copy1 takes pride of place over the other extant copies corrected by Bach. When the Bach Gesellschaft (hereafter BGA) published the "Goldberg Variations" in 18532, the editor, C. -

A Study of Musical Rhetoric in JS Bach's Organ Fugues

A Study of Musical Rhetoric in J. S. Bach’s Organ Fugues BWV 546, 552.2, 577, and 582 A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Keyboard Division of the College-Conservatory of Music March 2015 by Wei-Chun Liao BFA, National Taiwan Normal University, 1999 MA, Teachers College, Columbia University, 2002 MEd, Teachers College, Columbia University, 2003 Committee Chair: Roberta Gary, DMA Abstract This study explores the musical-rhetorical tradition in German Baroque music and its connection with Johann Sebastian Bach’s fugal writing. Fugal theory according to musica poetica sources includes both contrapuntal devices and structural principles. Johann Mattheson’s dispositio model for organizing instrumental music provides an approach to comprehending the process of Baroque composition. His view on the construction of a subject also offers a way to observe a subject’s transformation in the fugal process. While fugal writing was considered the essential compositional technique for developing musical ideas in the Baroque era, a successful musical-rhetorical dispositio can shape the fugue from a simple subject into a convincing and coherent work. The analyses of the four selected fugues in this study, BWV 546, 552.2, 577, and 582, will provide a reading of the musical-rhetorical dispositio for an understanding of Bach’s fugal writing. ii Copyright © 2015 by Wei-Chun Liao All rights reserved iii Acknowledgements The completion of this document would not have been possible without the help and support of many people. -

Gregory Butler. Bach's Clavier-Ubung III: the Mak Ing of a Print

Gregory Butler. Bach's Clavier-Ubung III: The Mak ing of a Print. With a Companion Study of the Canonic Variations on "Vom Himmel Hoch," BWV 769. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1990. 139 pp. When I read Gregory Butler's Bach's Clavier-Ubung III' The Making of a Print, I could not help but think of a remark made by Arthur Mendel at the first meeting of the American Bach Society some twenty years ago. At the conclusion of a round table on post-World War II developments in Bach research, a long session in which the manuscript studies of Alfred Durr, Georg von Dadelsen, and Robert Marshall were discussed in some detail, Mendel quipped, with a wry smile: "And if the original manuscripts have revealed a lot about Bach's working habits, wait until we take a closer look at the original prints!" The remark drew laughter, as Mendel intend ed, and struck one at the time as facetious, for how could the prints of Bach's works ever show as much about chronology and the compositional process as the manuscripts? The surviving manuscript materials, written by Bach and his copyists, display a wealth of information that can be unrav eled through source-critical investigation: revisions, corrections, organiza tional second thoughts. The prints, by contrast, appear inscrutable. Uni form and definitive in appearance, made by engravers rather than Bach or his assistants, they seem to be closed books, telling little-if anything about the genesis of the texts they contain. In the earliest volumes of the Neue Bach-Ausgabe (NBA), the original prints were viewed in precisely that way. -

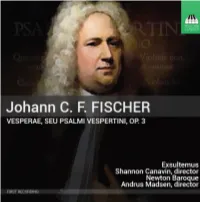

TOC 0364 CD Booklet.Indd

JOHANN CASPAR FERDINAND FISCHER Vesperae, seu Psalmi Vespertini, Op. 3 1 Blumen-Strauss (before 1736): Praeludium VIII 1:15 2 Domine ad adjuvandum 1:06 3 Beatus vir 3:23 4 Ariadne musica neo-organoedum (1702): Praeludium et Fuga IV 1:51 5 Conftebor 4:17 6 Ariadne musica neo-organoedum: Praeludium et Fuga XVIII 1:41 7 Credidi 2:03 8 Ariadne musica neo-organoedum: Praeludium et Fuga VIII 1:46 9 Nisi Dominus 3:28 10 Ariadne musica neo-organoedum: Praeludium et Fuga III 1:44 11 Lauda Jerusalem 5:20 12 Ariadne musica neo-organoedum: Praeludium et Fuga XVII 1:54 JOHANN CHRISTOPH PEZ Sonata in G minor 14:43 13 I Adagio 2:13 14 II Allegro 2:23 15 III Adagio 1:25 16 IV Allegro 4:21 17 V Adagio 0:41 18 VI Gigue 1:40 2 JOHANN CASPAR FERDINAND FISCHER FISCHER 19 Magnifcat 6:31 Vesperae, seu Psalmi Vespertini, Op. 3 PEZ Duplex Genius sive Gallo-Italus Instrumentorum Concentus (1696): Sonata Quinta 9:08 20 Blumen-Strauss (before 1736): Praeludium VIII 1:15 I Adagio 1:58 21 Domine ad adjuvandum 1:06 II Allegro 1:39 22 Beatus vir 3:23 III Adagio 3:03 23 Ariadne musica neo-organoedum (1702): Praeludium et Fuga IV 1:51 IV Vivace 1:28 Conftebor 4:17 FISCHER Ariadne musica neo-organoedum: Praeludium et Fuga XVIII 1:41 24 Lytaniae Lauretanae VII (1711): Salve Regina 5:27 Credidi 2:03 TT 63:35 Ariadne musica neo-organoedum: Praeludium et Fuga VIII 1:46 Nisi Dominus 3:28 Exsultemus Ariadne musica neo-organoedum: Praeludium et Fuga III 1:44 Shannon Canavin and Margot Rood, sopranos Lauda Jerusalem 5:20 Thea Lobo and Gerrod Pagenkopf, altos Ariadne musica neo-organoedum: -

Baroque and Classical Style in Selected Organ Works of The

BAROQUE AND CLASSICAL STYLE IN SELECTED ORGAN WORKS OF THE BACHSCHULE by DEAN B. McINTYRE, B.A., M.M. A DISSERTATION IN FINE ARTS Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Chairperson of the Committee Accepted Dearri of the Graduate jSchool December, 1998 © Copyright 1998 Dean B. Mclntyre ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am grateful for the general guidance and specific suggestions offered by members of my dissertation advisory committee: Dr. Paul Cutter and Dr. Thomas Hughes (Music), Dr. John Stinespring (Art), and Dr. Daniel Nathan (Philosophy). Each offered assistance and insight from his own specific area as well as the general field of Fine Arts. I offer special thanks and appreciation to my committee chairperson Dr. Wayne Hobbs (Music), whose oversight and direction were invaluable. I must also acknowledge those individuals and publishers who have granted permission to include copyrighted musical materials in whole or in part: Concordia Publishing House, Lorenz Corporation, C. F. Peters Corporation, Oliver Ditson/Theodore Presser Company, Oxford University Press, Breitkopf & Hartel, and Dr. David Mulbury of the University of Cincinnati. A final offering of thanks goes to my wife, Karen, and our daughter, Noelle. Their unfailing patience and understanding were equalled by their continual spirit of encouragement. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii ABSTRACT ix LIST OF TABLES xi LIST OF FIGURES xii LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES xiii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS xvi CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1 11. BAROQUE STYLE 12 Greneral Style Characteristics of the Late Baroque 13 Melody 15 Harmony 15 Rhythm 16 Form 17 Texture 18 Dynamics 19 J. -

Web Feature 17.1 1

Kevin Holm-Hudson Music Theory Remixed, Web Feature 17.1 1 Web Feature 17.1 Tonality as a journey The idea of key relationships in music as “distances” to be traveled goes back at least as far as the eighteenth century; in 1702 the composer J. K. F. Fischer published a collection of pieces in nineteen different keys (plus the Phrygian mode) entitled Ariadne musica. The work’s title is a reference to Ariadne’s ball of thread that guided Theseus through the labyrinth in Greek mythology; thus, this was a set of pieces that systematically and collectively explored the relationships among the different keys and “guided” the performer among them. Similarly, J. S. Bach’s son Carl Phillipp Emanuel Bach (1714– 1788) described in his influential book, Essay on the True Art of Playing Keyboard Instruments (1762), how a performer might negotiate a dramatic path among keys that had different perceived “distances” from one another: “in a free fantasia modulation may be made to closely related, remote, and all other keys.”1 He also points out: “It is one of the beauties of improvisation to feign modulation to a new key through a formal cadence and then move off in another direction. This and other rational deceptions make a fantasia attractive.”2 All the same, he cautions the performer to use restraint in structuring the improvisation in a manner that would befit a narrative, not veering off into the “adventure” at the beginning or returning “home” at the end too early: When only little time is available for the display of craftsmanship, the performer should not wander into too remote keys, for the performance must soon come to an end. -

GERMAN ORGAN MUSIC Volume 1 Fischer Praetorius Bohm Scheidemann and Others Joseph Payne, Organ GERMAN ORGAN MUSIC VOLUME 1

8.550964 GERMAN ORGAN MUSIC Volume 1 Fischer Praetorius Bohm Scheidemann and others Joseph Payne, Organ GERMAN ORGAN MUSIC VOLUME 1 Organ music of the German-speaking countries is vast and varied, and more than anywhere else in Europe, it reached considerable complexity by the early 15th century. This repertory reflects the complex development of large, fixed organs, about which few generalizations can be made, as well as the more uniform evolution of smaller forms of organs. Among these was the portative, a small portable organ blown by a pair of bellows operated by one of the player's hands. Capable of performing only one part, this was a "monophonic" instrument used mainly in ensembles with other instruments and singers in the performance of polyphonic music. Somewhat larger and more or less stationary was the positive. It employed bellows that were operated by a second person, enabling the organist to use both hands so that several notes might be played simultaneously on a chromatic keyboard. Both these smaller types of organ employed flue pipes, while reed pipes were used in a third type, the regal. (There are many depictions of these small organs; a famous one can be found on the altar painting by Jan van Eyck at St. Bavo in Ghent). Towards the end of the Middle Ages, many tonal and mechanical features of the smaller organs were incorporated into the resources of the full-sized church Orgelwerk. This was a decisive step towards the modern organ: the organ came to be regarded as a composite of several instruments of various capabilities and functions, its resources controlled from several different keyboards.