Cake and Cockhorse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WIN a ONE NIGHT STAY at the OXFORD MALMAISON | OXFORDSHIRE THAMES PATH | FAMILY FUN Always More to Discover

WIN A ONE NIGHT STAY AT THE OXFORD MALMAISON | OXFORDSHIRE THAMES PATH | FAMILY FUN Always more to discover Tours & Exhibitions | Events | Afternoon Tea Birthplace of Sir Winston Churchill | World Heritage Site BUY ONE DAY, GET 12 MONTHS FREE ATerms precious and conditions apply.time, every time. Britain’sA precious time,Greatest every time.Palace. Britain’s Greatest Palace. www.blenheimpalace.com Contents 4 Oxford by the Locals Get an insight into Oxford from its locals. 8 72 Hours in the Cotswolds The perfect destination for a long weekend away. 12 The Oxfordshire Thames Path Take a walk along the Thames Path and enjoy the most striking riverside scenery in the county. 16 Film & TV Links Find out which famous films and television shows were filmed around the county. 19 Literary Links From Alice in Wonderland to Lord of the Rings, browse literary offerings and connections that Oxfordshire has created. 20 Cherwell the Impressive North See what North Oxfordshire has to offer visitors. 23 Traditions Time your visit to the county to experience at least one of these traditions! 24 Transport Train, coach, bus and airport information. 27 Food and Drink Our top picks of eateries in the county. 29 Shopping Shopping hotspots from around the county. 30 Family Fun Farm parks & wildlife, museums and family tours. 34 Country Houses and Gardens Explore the stories behind the people from country houses and gardens in Oxfordshire. 38 What’s On See what’s on in the county for 2017. 41 Accommodation, Tours Broughton Castle and Attraction Listings Welcome to Oxfordshire Connect with Experience Oxfordshire From the ancient University of Oxford to the rolling hills of the Cotswolds, there is so much rich history and culture for you to explore. -

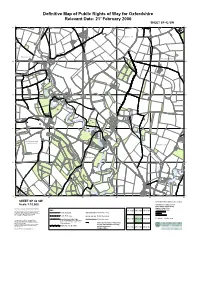

Definitive Map of Public Rights of Way for Oxfordshire Relevant Date: 21St February 2006 Colour SHEET SP 42 SW

Definitive Map of Public Rights of Way for Oxfordshire Relevant Date: 21st February 2006 Colour SHEET SP 42 SW 40 41 42 43 44 45 0004 8900 9600 4900 7100 0003 0006 2800 0003 2000 3700 5400 7100 8800 3500 5500 7000 8900 0004 0004 5100 8000 0006 25 365/1 Woodmans Cottage 25 Spring Close 9 202/31 365/3 202/36 1392 365/2 8891 365/17 202/2 400/2 8487 St Mary's Church 5/23 4584 36 0682 8381 Drain 202/30 CHURCH LANE 7876 2/56 20 8900 7574 365/2 2772 Westcot Barton CP 5568 2968 1468 1267 365/3 9966 4666 202/ 0064 8964 0064 5064 5064 202/29 Drain Spring 1162 0961 11 202/31 202/56 1359 0054 0052 365/1 0052 5751 0050 Oathill Farm Oathill Lodge 264/8 0050 264/7 6046 The Folly 0044 0044 6742 264/8 202/32 264/7 3241 7841 0940 7640 1839 2938 Drain 3637 7935 0033 0032 0032 0033 1028 4429 El Sub Sta 3729 7226 202/11 3124 6423 6023 Pond 0022 202/30 365/28 8918 0218 2618 7817 9217 4216 0015 0015 Spring 8214 2014 Willowbrook Cottage 9610 Radford House Enstone CP Radford 0001 House 202/32 Charlotte Cottage 224/1 Spring Steeple Barton CP Reservoir Nelson's Cottage 0077 6400 2000 3900 6200 2400 5000 7800 0005 3800 6400 0001 1300 3900 6100 0005 RADFORD Convent Cottage 8700 2600 6400 2000 3900 0002 1300 24 Convent Cottage 0002 5000 7800 0005 3800 4800 6400 365/4 0001 3900 6100 0005 24 Holly Tree House Brook Close 0005 Brook Close White House Farm Radford Lodge 365/3 365/5 365/4 8889 Radford Farm 0084 6583 8083 0084 202/33 4779 0077 0077 0077 8976 3175 202/45 9471 224/1 Barton Leys Farm Pond 2669 8967 Mill House Kennels 7665 Pond 202/44 2864 6561 6360 Glyme The -

Oxfordshire Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by Bride’s Parish Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1635 Gerrard, Ralph --- Eustace, Bridget --- 1635 Saunders, William Caversham Payne, Judith --- 1635 Lydeat, Christopher Alkerton Micolls, Elizabeth --- 1636 Hilton, Robert Bloxham Cook, Mabell --- 1665 Styles, William Whatley Small, Simmelline --- 1674 Fletcher, Theodore Goddington Merry, Alice --- 1680 Jemmett, John Rotherfield Pepper Todmartin, Anne --- 1682 Foster, Daniel --- Anstey, Frances --- 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1683 Hatherill, Anthony --- Matthews, Jane --- 1684 Davis, Henry --- Gomme, Grace --- 1684 Turtle, John --- Gorroway, Joice --- 1688 Yates, Thos Stokenchurch White, Bridgett --- 1688 Tripp, Thos Chinnor Deane, Alice --- 1688 Putress, Ricd Stokenchurch Smith, Dennis --- 1692 Tanner, Wm Kettilton Hand, Alice --- 1692 Whadcocke, Deverey [?] Burrough, War Carter, Elizth --- 1692 Brotherton, Wm Oxford Hicks, Elizth --- 1694 Harwell, Isaac Islip Dagley, Mary --- 1694 Dutton, John Ibston, Bucks White, Elizth --- 1695 Wilkins, Wm Dadington Whetton, Ann --- 1695 Hanwell, Wm Clifton Hawten, Sarah --- 1696 Stilgoe, James Dadington Lane, Frances --- 1696 Crosse, Ralph Dadington Makepeace, Hannah --- 1696 Coleman, Thos Little Barford Clifford, Denis --- 1696 Colly, Robt Fritwell Kilby, Elizth --- 1696 Jordan, Thos Hayford Merry, Mary --- 1696 Barret, Chas Dadington Hestler, Cathe --- 1696 French, Nathl Dadington Byshop, Mary --- Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by -

SUPPLEMENT to the LONDON GAZETTE, Io FEBKUAEY,'1917. 1615

. .,. -, --.-,.- .^- -. - SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, io FEBKUAEY,'1917. 1615 - --• Silver Medal. Lieutenant-Colonel (temporary Colonel) Archi- 'T.2/017277 Driver Joeepli Bernard Elton bald Philip- Dpuglas, Royal Artillery. \- - North, Army Service Corps (British' Major Alexander Coburn Edwardes, Grena- Adriatic Mission). diers, Indian Army. -. - Captain (temporary Lieutenant-Colonel) Wil- (August 27th, 1916.) liam Frederick Oliver Faviell, Worcester- shire Regiment. Qrder of the White Eagle, 2nd Class (with Lieutenant-Colonel Theodore Fraser, C.M.Gi, Swords). Royal Engineers. Major (temporary Lieutenant-Colonel) William .Major-General Maitland Cowper, C.I.E., Welch Barrows Gover, Cheshire Regiment, Indian Army. Royal Warwickshire Regiment. Major-General Arthur Wigram Money, C.B. Major (temporary Lieutenant-Colonel) Charles ^Surgeon-General Francis Harper Treherne, Basil Lees Greenstreet, Royal Engineers. C.M.G., F.R.C.S. Major (temporary Lieutenant-Colonel) William Allardice Hamilton, Connaught Rangers. "Order of the White Eagle, 3rd Class (with Major (temporary Lieutenant-Colonel) Gfeorge Swords). Melbourne Herbert, D.S.O., Dorsetshire Lieutenant-Colonel (temporary Brigadier- Regiment. General) Herbert Henry Austin, C.M.G., Major and Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel Reginald D.S.O., Royal Engineers.' John Thoroton Hildyafd, D.S.O., Royal .Major Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel (temporary West Kent Regiment. Brigadier-General) Herbert Jose Pierson Captain (temporary Major) Henry Walter Browne, Gurkha Biflesi, Indian .Army. Dunlop Hill, Cavalry, Indian Army. -Lieutenant-Colonel (temporary Brigadier- Major (Brevet" Lieutenant-Colonel) Herbert General) Leslie Warner Yule Campbell, Reginald Hopwood, Light Cavalry, Indian Punjabis, Indian Army. Army. -Colonel and Brigadier-General Gerard Chris- Major Walter Stewart Leslie, Punjabis; tian, D.S.O. Indian Army. •Colonel and temp. Brigadier-General James Major Alexander Charles Broughton Mackin- Archibald Douglas, C.M.G., Indian Army. -

Museums and Galleries of Oxfordshire 2014

Museums and Galleries of Oxfordshire 2014 includes 2014 Museum and Galleries D of Oxfordshire Competition OR SH F IR X E O O M L U I S C MC E N U U M O S C Soldiers of Oxfodshire Museum, Woodstock www.oxfordshiremuseums.org The SOFO Museum Woodstock By a winning team Architects Structural Project Services CDM Co-ordinators Engineers Management Engineers OXFORD ARCHITECTS FULL PAGE AD museums booklet ad oct10.indd 1 29/10/10 16:04:05 Museums and Galleries of Oxfordshire 2012 Welcome to the 2012 edition of Museums or £50, there is an additional £75 Blackwell andMuseums Galleries of Oxfordshire and Galleries. You will find oftoken Oxfordshire for the most questions answered2014 detailsWelcome of to 39 the Museums 2014 edition from of everyMuseums corner and £75correctly. or £50. There is an additional £75 token for ofGalleries Oxfordshire of Oxfordshire, who are your waiting starting to welcomepoint the most questions answered correctly. Tokens you.for a journeyFrom Banbury of discovery. to Henley-upon-Thames, You will find details areAdditionally generously providedthis year by we Blackwell, thank our Broad St, andof 40 from museums Burford across to Thame,Oxfordshire explore waiting what to Oxford,advertisers and can Bloxham only be redeemed Mill, Bloxham in Blackwell. School, ourwelcome rich heritageyou, from hasBanbury to offer. to Henley-upon- I wouldHook likeNorton to thank Brewery, all our Oxfordadvertisers London whose Thames, all of which are taking part in our new generousAirport, support Smiths has of allowedBloxham us and to bring Stagecoach this Thecompetition, competition supported this yearby Oxfordshire’s has the theme famous guidewhose to you, generous and we supportvery much has hope allowed that us to Photo: K T Bruce Oxfordshirebookseller, Blackwell. -

Official Records

SECTION B JUNE 19, 2017 BANKER & TRADESMAN Official Records MASSACHUSETTS MARKET STATISTICS INDEX Volume of Mortgages County Sales Charts In This Week’s Issue for Single-Family Homes None 6000$6,0006000 Both Both 5000 Real Estate Records 5000$5,000 Renance Renance 4000 Purchase PAGE COUNTY TRANSACTIONS THRU PAGE COUNTY TRANSACTIONS THRU 4000$4,0003000 B2 SuffolkPurchase ........ 06/02/17 B14 Franklin ....... 06/02/17 2000 $3,000 B6 Barnstable ..... 06/02/17 B15 Hampden ...... 06/02/17 3000 1000 0 B7 Berkshire Middle 06/02/17 B17 Hampshire ..... 06/02/17 2000$2,000 Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun B8 Berkshire North .06/02/17 B17 Middlesex North. 06/02/17 $1,000 1000 B8 Berkshire South .06/02/17 B19 Middlesex South. 06/02/17 0$0 B8 Bristol Fall River 06/02/17 B24 Nantucket ...... 06/02/17 JunMay JulJun. AuJul.g SeAug.p OcSept.t NoOct.v DeNov.c JanDec. FeJan.b MaMayr ApMar.r MaApr.y JuMayn ’16 ’17 B9 Bristol North ... 06/02/17 B24 Norfolk ........ 06/02/17 B10 Bristol South ... 06/02/17 B27 Plymouth ...... 06/02/17 6600 $6,600 BothMonth Purchase Refinance Both 6600 Both B11 Dukes ......... 06/02/17 B30 Worcester ...... 06/02/17 5500 5500 $5,500 Renance Renance 4400 Purchase B11 Essex North .... 06/02/17 B34 Worcester North. 06/02/17 $4,4004400 Purchase 3300 May 2013 $1,399 $4,236 $5,636 B12 Essex South .... 06/02/17 2200 $3,3003300 May 2014 $1,394 $1,392 $2,786 1100 0 2200 May 2015 $1,335 $2,573 $3,908 Fe$2,200b. -

Cake & Cockhorse

CAKE & COCKHORSE BANBURY HISTORICAL SOCIETY SUMMER 1979. PRICE 50p. ISSN 0522-0823 BANBURY HISTORICAL SOCIETY President: The Lord Saye and Sele chairman: Alan Donaldson, 2 Church Close, Adderbury, Banbury. Magazine Editor: D. E. M. Fiennes, Woadmill Farm, Broughton, Banbury. Hon. Secretary: Hon. Treasurer: Mrs N.M. Clifton Mr G. de C. Parmiter, Senendone House The Halt, Shenington, Banbury. Hanwell, Banbury.: (Tel. Edge Hill 262) (Tel. Wroxton St. Mary 545) Hm. Membership Secretary: Records Series Editor: Mrs Sarah Gosling, B.A., Dip. Archaeol. J.S. W. Gibson, F.S.A., Banbury Museum, 11 Westgate, Marlborough Road. Chichester PO19 3ET. (Tel: Banbury 2282) (Tel: Chichester 84048) Hon. Archaeological Adviser: J.H. Fearon, B.Sc., Fleece Cottage, Bodicote, Banbury. committee Members: Dr. E. Asser, Mr. J.B. Barbour, Miss C.G. Bloxham, Mrs. G. W. Brinkworth, B.A., David Smith, LL.B, Miss F.M. Stanton Details about the Society’s activities and publications can be found on the inside back cover Our cover illustration is the portrait of George Fox by Chinn from The Story of Quakerism by Elizabeth B. Emmott, London (1908). CAKE & COCKHORSE The Magazine of the Banbury Historical Society. Issued three times a year. Volume 7 Number 9 Summer 1979 Barrie Trinder The Origins of Quakerism in Banbury 2 63 B.K. Lucas Banbury - Trees or Trade ? 270 Dorothy Grimes Dialect in the Banbury Area 2 73 r Annual Report 282 Book Reviews 283 List of Members 281 Annual Accounts 2 92 Our main articles deal with the origins of Quakerism in Banbury and with dialect in the Ranbury area. -

Volume 08 Number 02

CAKE & COCKHORSE BA4NBURY HISTORICAL SOCIETY SPRING 1980. PRICE 50p. ISSN 0522-0823 BANBURY HISTORICAL SOCIETY President: The Lord Saye and Sele Chairman: J. S.W. Gibson, Harts Cottage, Church Hanborough, Oxford. Magazine Editor: D. E. M. Fiennes, Woadmill Farm, Broughton, Banbury. Hon. Secretary: Hon. Treasurer: t Mrs N.M. Clifton, Mr G. de C. Parmiter, Senendone House, The Halt, Shenington, Banbury. Hanwell, Banbury, (Tel: Edge Hill 262) (Tel: Wroxton St. Mary 545) Hon. Membership Secretary: Records Series Editor: Mrs Sarah Gosling, J. S. W. Gibson, Banbury Museum, Harts Cottage, Marlborough Road. Church Hanborough, (Tel: Banbury 2282) Oxford OX7 2AB. Hon. Archaeological Adviser: J.H. Fearon, Fleece Cottage, Bodic.nt.e, Einb1iry. Committee Members: Dr E. Asser, Miss C.G. Bloxham, Mrs G.W. Brinkworth, Mr A. DonaIdson, Mr N. Griffiths, Miss F.M. Stanton Details about the Society’s activities and publications can be found on the inside back cover Our cover picture shows Broughton church and its tower, and is reproduced, by kind permission of the artist, from “Churches of the Ban- bury Area n, by George Graham Walker. CAKE & COCKHORSE The Magazine of the Banbury Historical Society. Issued three times a year. Volume 8 Number 2 Spring 1980 J. P. Brooke-Little Editorial 25 D.E.M. Fiennes A Study in Family Relationships: 27 William Fiennes and Margaret Wykeham Nicholas Cooper Book Review: 'Broughton Castle 46 Sue Read and Icehouses: An Investigation at Wroxton 48 John Seagrave With a most becoming, but I dare to suggest, unnecessary modesty, the Editor of Take and Cockhorse" has invited me to write this Editorial as he himself is the author of the principal article in this issue. -

New Brewery Coming to Our Branch Beer on Tap Is Pleased to Announce That We Should Soon Have a New Brewery in the North Oxon CAMRA Branch

Issue 54 – Autumn 2013 FREE – Please take one Newsletter of North Oxfordshire Branch of CAMRA New Brewery Coming To Our Branch Beer on Tap is pleased to announce that we should soon have a new brewery in the North Oxon CAMRA Branch. The Turpin Brewery, named after its location at Turpin’s Lodge, Hook Norton hopes to be supplying beers regularly after months of trialling brews. With the exception of our long-standing favourite Hook Norton Brewery, the only other breweries we have seen in our Branch’s recent history have been the Bodicote Brewery John Romer (left) meets CAMRA North Oxon Branch Chairman John Bellinger (centre) and Branch member Douglas Rudlin at the Turpin Brewery, Hook Norton (which brewed for over 20 years in The Plough, Bodicote) and to the Hook Norton area. John Turpin Brewery at his premises the short-lived Banbury Brewery Romer, who has a technical at Turpin’s Lodge, Hook Norton and Henry’s Butchers Yard engineering background, has (the Horse Riding Centre). Brewery (which opened briefly set up, designed and built the Continued on page 3 in Chipping Norton), along with the Cotswold Brewing Co. Good Beer Guide 2014 Launch (which at the time only brewed lager) but which has since At The White Horse, Banbury moved across the border into Gloucestershire. On Thursday 12th September, the It was a close thing a couple North Oxfordshire Branch held a of years ago when XT Brewery launch event to mark the publication of initially wanted to open for busi- the 2014 edition of CAMRA’s premiere ness at Heyford Wharf, but sadly publication, the Good Beer Guide, at it was not to be, as they eventu- the White Horse in North Bar Street, ally plumped for Long Crendon Banbury at 8.00pm. -

The Warriner School

The Warriner School PLEASE CAN YOU ENSURE THAT ALL STUDENTS ARRIVE 5 MINUTES PRIOR TO THE DEPARTURE TIME ON ALL ROUTES From 15th September- Warriner will be doing an earlier finish every other Weds finishing at 14:20 rather than 15:00 Mon - Fri 1-WA02 No. of Seats AM PM Every other Wed 53 Sibford Gower - School 07:48 15:27 14:47 Burdrop - Shepherds Close 07:50 15:25 14:45 Sibford Ferris - Friends School 07:53 15:22 14:42 Swalcliffe - Church 07:58 15:17 14:37 Tadmarton - Main Street Bus Stop 08:00 15:15 14:35 Lower Tadmarton - Cross Roads 08:00 15:15 14:35 Warriner School 08:10 15:00 14:20 Heyfordian Travel 01869 241500 [email protected] 1-WA03/1-WA11 To be operated using one vehicle in the morning and two vehicles in the afternoon Mon - Fri 1-WA03 No. of Seats AM PM Every other Wed 57 Hempton - St. John's Way 07:45 15:27 14:42 Hempton - Chapel 07:45 15:27 14:42 Barford St. Michael - Townsend 07:50 15:22 14:37 Barford St. John - Farm on the left (Street Farm) 07:52 15:20 14:35 Barford St. John - Sunnyside Houses (OX15 0PP) 07:53 15:20 14:35 Warriner School 08:10 15:00 14:20 Mon - Fri 1-WA11 No. of Seats AM PM Every other Wed 30 Barford St. John 08:20 15:35 15:35 Barford St. Michael - Lower Street (p.m.) 15:31 15:31 Barford St. -

Treasure Houses of Southern England

Treasure Houses of Southern England Behind the Scenes of the Stately Homes of England May 3rd - 12th 2020 We are pleased to present the first in a two-part series that delves into the tales and traditions of the English aristocracy in the 20th century. The English class system really exists nowhere else in the world, mainly because England has never had the kind of violent social revolution that has taken away the ownership of the land from the families that have ruled it since medieval times. Vast areas of the country are still owned by families that can trace their heritage back to the Norman knights who accompanied William the Conqueror. Here is our invitation to discover how this system has come Blenheim Palace about and to experience the fabulous legacy that it has bequeathed to the nation. We have included a fascinating array of visits, to houses both great and small, private and public, spanning the centuries from the Norman invasion to the Victorian era. This spring, join Discover Europe, and like-minded friends, for a look behind the scenes of Treasure Houses of Southern England. The cost of this itinerary, per person, double occupancy is: Land only (no airfare included): $4980 Single supplement: $ 960 Airfares are available from many U.S. cities. Please call for details. The following services are included: Hotels: 8 nights’ accommodation in first-class hotels including all hotel taxes and service charges Coaching: All ground transportation as detailed in the itinerary Meals: Full breakfast daily, 4 dinners Guides: Discover Europe tour guide throughout Baggage: Porterage of one large suitcase per person Entrances: Entrance fees to all sites included in the itinerary, including private tours of Waddesdon Manor, Blenheim Palace and Stonor Park (all subject to final availability) Ightham Mote House Please note that travel insurance is not included on this tour. -

Of Considerable Interest Locally Is the Mary Robinson Deddington Charity Estates’ Planning Application for Alterations Next Advertising Copy Date: to the Town Hall

Deddington News June 2010 – 1 THIS MONTH’S EDITOR Jill Cheeseman Next copy date: 19 JUNE 2010 What a pity that again we shall not get a Parish Council election Copy please to (see PC notes, p2). Of considerable interest locally is the Mary Robinson Deddington Charity Estates’ planning application for alterations Next advertising copy date: to the Town Hall. Details of how to access the plans are provided 10 JUNE on p2. I would encourage as many people as possible to take an interest in the proposed changes to this historic building. Managing Editors: Jill Cheeseman 338609 Mary Robinson 338272 JUNE [email protected] Wed 2 Photographic Society: Don Byatt, ‘Keeping it Simple – a Talk Parish affairs CorrEsP: with Digital Prints’, Cartwright Hotel, Aynho, 7.30pm Charles Barker 337747 Sat 5 British Legion: Disco with Barney, 8.30pm Mon 7 Monday Morning Club: Coffee Morning, 10.30am–noon Clubs’ Editor: Alison Day 337204 Tue 8 WI: ‘Spinning the Yarn’, Ruth Power, Holly Tree, 7.30pm [email protected] Wed 9 History Society: A guided walk round the parish of St Thomas the Martyr, West Oxford diary Editor: Thu 10 Monday Morning Club: Film evening, Julie and Julia, Holly Jean Flux 338153 Tree, 6.30pm [email protected] Thu 10 Friends of Deddington Festival: Reception, Parish Church, fEaturEs’ Editor: 6.30pm Molly Neild 338521 Fri 11 Deddington Festival: Deddington Rocks, Market Place, 6.30pm [email protected] Mon 14 DOGS: Full day’s golf at Burford Golf Club ChurCh & ChaPEl Editor: Tue 15 Parish Council Meeting: