Volume 08 Number 02

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archaeological Work in Oxford, 2012

Oxoniensia 78 txt 4+index_Oxoniensia 17/11/2013 12:05 Page 213 ROMANO-BRITISH VILLA AT COMBE 213 NOTES Archaeological Work in Oxford, 2012 In 2012 the Heritage and Specialist Services Team completed the Oxford Archaeological Plan (OAP). The resulting resource assessment, research agenda and characterisation reports are available on the council website, along with a six-year Archaeological Action Plan for the city. The year also saw a number of substantial city centre projects resulting from the expansion of college facilities, and some notable new information resulting from small-scale commercial and domestic development. Provisional summaries for selected sites are provided below. SELECTED PROJECTS 19 St Andrew’s Lane, Headington In January JMHS carried out an archaeological evaluation prior to the construction of a small extension at 19 St Andrew’s Lane. The evaluation recorded a post-medieval well and a series of cess pits filled with dump deposits containing animal bone, late-medieval and early post- medieval pottery and brick. At least six post holes from an unidentified structure possibly post- dating the pits were recorded. Nos. 6–7 High Street (Jack Wills, formerly Ryman’s Stationers) In February three test pits were excavated in the basement of Nos. 6–7 High Street by OA. A number of medieval pits containing domestic and butchery waste were recorded, along with a stone drain or wall foundation. The backfill of one feature contained a fired clay annular discoidal loom weight of likely early to middle Anglo-Saxon date (c.400–850). In June a lift pit was excavated in the basement revealing in section the edge of a possible wood-lined pit, potentially a ‘cellar pit’. -

11 Witney - Hanborough - Oxford

11 Witney - Hanborough - Oxford Mondays to Saturdays notes M-F M-F S M-F M-F Witney Market Square stop C 06.14 06.45 07.45 - 09.10 10.10 11.15 12.15 13.15 14.15 15.15 16.20 - Madley Park Co-op 06.21 06.52 07.52 - - North Leigh Masons Arms 06.27 06.58 07.58 - 09.18 10.18 11.23 12.23 13.23 14.23 15.23 16.28 17.30 Freeland Broadmarsh Lane 06.35 07.06 08.07 07.52 09.27 10.27 11.32 12.32 13.32 14.32 15.32 16.37 17.40 Long Hanborough New Road 06.40 07.11 08.11 07.57 09.31 10.31 11.36 12.36 13.36 14.36 15.36 16.41 Eynsham Spareacre Lane 06.49 07.21 08.20 09.40 10.40 11.45 12.45 13.45 14.45 15.45 16.50 Eynsham Church 06.53 07.26 08.24 08.11 09.44 10.44 11.49 12.49 13.49 14.49 15.49 16.54 17.49 Botley Elms Parade 07.06 07.42 08.33 08.27 09.53 10.53 11.58 12.58 13.58 14.58 15.58 17.03 18.00 Oxford Castle Street 07.21 08.05 08.47 08.55 10.07 11.07 12.12 13.12 13.12 15.12 16.12 17.17 18.13 notes M-F M-F S M-F M-F S Oxford Castle Street E2 07.25 08.10 09.10 10.15 11.15 12.15 13.15 14.15 15.15 16.35 16.35 17.35 17.50 Botley Elms Parade 07.34 08.20 09.20 10.25 11.25 12.25 13.25 14.25 15.25 16.45 16.50 17.50 18.00 Eynsham Church 07.43 08.30 09.30 10.35 11.35 12.35 13.35 14.35 15.35 16.55 17.00 18.02 18.10 Eynsham Spareacre Lane 09.34 10.39 11.39 12.39 13.39 14.39 15.39 16.59 17.04 18.06 18.14 Long Hanborough New Road 09.42 10.47 11.47 12.47 13.47 14.47 15.47 17.07 17.12 18.14 18.22 Freeland Broadmarsh Lane 07.51 08.38 09.46 10.51 11.51 12.51 13.51 14.51 15.51 17.11 17.16 18.18 18.26 North Leigh Masons Arms - 08.45 09.55 11.00 12.00 13.00 -

George Edmund Street

DOES YOUR CHURCH HAVE WORK BY ONE OF THE GREATEST VICTORIAN ARCHITECTS? George Edmund Street Diocesan Church Building Society, and moved to Wantage. The job involved checking designs submitted by other architects, and brought him commissions of his own. Also in 1850 he made his first visit to the Continent, touring Northern France. He later published important books on Gothic architecture in Italy and Spain. The Diocese of Oxford is extraordinarily fortunate to possess so much of his work In 1852 he moved to Oxford. Important commissions included Cuddesdon College, in 1853, and All Saints, Boyne Hill, Maidenhead, in 1854. In the next year Street moved to London, but he continued to check designs for the Oxford Diocesan Building Society, and to do extensive work in the Diocese, until his death in 1881. In Berkshire alone he worked on 34 churches, his contribution ranging from minor repairs to complete new buildings, and he built fifteen schools, eight parsonages, and one convent. The figures for Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire are similar. Street’s new churches are generally admired. They include both grand town churches, like All Saints, Boyne Hill, and SS Philip and James, Oxford (no longer in use for worship), and remarkable country churches such as Fawley and Brightwalton in Berkshire, Filkins and Milton- under-Wychwood in Oxfordshire, and Westcott and New Bradwell in Buckinghamshire. There are still some people for whom Victorian church restoration is a matter for disapproval. Whatever one may think about Street’s treatment of post-medieval work, his handling of medieval churches was informed by both scholarship and taste, and it is George Edmund Street (1824–81) Above All Saints, Boyne His connection with the Diocese a substantial asset for any church to was beyond doubt one of the Hill, Maidenhead, originated in his being recommended have been restored by him. -

Oxfordshire Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by Bride’s Parish Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1635 Gerrard, Ralph --- Eustace, Bridget --- 1635 Saunders, William Caversham Payne, Judith --- 1635 Lydeat, Christopher Alkerton Micolls, Elizabeth --- 1636 Hilton, Robert Bloxham Cook, Mabell --- 1665 Styles, William Whatley Small, Simmelline --- 1674 Fletcher, Theodore Goddington Merry, Alice --- 1680 Jemmett, John Rotherfield Pepper Todmartin, Anne --- 1682 Foster, Daniel --- Anstey, Frances --- 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1683 Hatherill, Anthony --- Matthews, Jane --- 1684 Davis, Henry --- Gomme, Grace --- 1684 Turtle, John --- Gorroway, Joice --- 1688 Yates, Thos Stokenchurch White, Bridgett --- 1688 Tripp, Thos Chinnor Deane, Alice --- 1688 Putress, Ricd Stokenchurch Smith, Dennis --- 1692 Tanner, Wm Kettilton Hand, Alice --- 1692 Whadcocke, Deverey [?] Burrough, War Carter, Elizth --- 1692 Brotherton, Wm Oxford Hicks, Elizth --- 1694 Harwell, Isaac Islip Dagley, Mary --- 1694 Dutton, John Ibston, Bucks White, Elizth --- 1695 Wilkins, Wm Dadington Whetton, Ann --- 1695 Hanwell, Wm Clifton Hawten, Sarah --- 1696 Stilgoe, James Dadington Lane, Frances --- 1696 Crosse, Ralph Dadington Makepeace, Hannah --- 1696 Coleman, Thos Little Barford Clifford, Denis --- 1696 Colly, Robt Fritwell Kilby, Elizth --- 1696 Jordan, Thos Hayford Merry, Mary --- 1696 Barret, Chas Dadington Hestler, Cathe --- 1696 French, Nathl Dadington Byshop, Mary --- Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by -

Initial Document Template

West Oxfordshire District Council – DELEGATED ITEMS Agenda Item No. 5 Application Types Key Suffix Suffix ADV Advertisement Consent LBC Listed Building Consent CC3REG County Council Regulation 3 LBD Listed Building Consent - Demolition CC4REG County Council Regulation 4 OUT Outline Application CM County Matters RES Reserved Matters Application FUL Full Application S73 Removal or Variation of Condition/s HHD Householder Application POB Discharge of Planning Obligation/s CLP Certificate of Lawfulness Proposed CLE Certificate of Lawfulness Existing CLASSM Change of Use – Agriculture to CND Discharge of Conditions Commercial PDET28 Agricultural Prior Approval HAZ Hazardous Substances Application PN56 Change of Use Agriculture to Dwelling PN42 Householder Application under Permitted POROW Creation or Diversion of Right of Way Development legislation. TCA Works to Trees in a Conservation Area PNT Telecoms Prior Approval TPO Works to Trees subject of a Tree NMA Non Material Amendment Preservation Order WDN Withdrawn FDO Finally Disposed Of Decision Description Decision Description Code Code APP Approve RNO Raise no objection REF Refuse ROB Raise Objection P1REQ Prior Approval Required P2NRQ Prior Approval Not Required P3APP Prior Approval Approved P3REF Prior Approval Refused P4APP Prior Approval Approved P4REF Prior Approval Refused West Oxfordshire District Council – DELEGATED ITEMS Application Number. Ward. Decision. 1. 17/02767/CND Milton Under Wychwood APP Discharge of condition 5 Highway details (15/03128/OUT). Land South Of High Street Milton Under Wychwood Mr Andrew Smith 2. 18/02366/FUL Burford APP Affecting a Conservation Area Change of use of land for the permanent siting of one caravan for use by the Site Warden at the Wysdom Touring Park (Retrospective). -

Wychwood Walk No. 6: North Leigh

Wychwood Walk No. 6: North Leigh - East End Approximately 4 miles / 6.25 km Parking: Park Road and Perrott Close TL - Turn left BL - Bear left (Please park with consideration to residents) TR - Turn right BR - Bear right Part of a series of circular walks that link in with The Wychwood Way 5 At the far side of the field take the right 6 Opposite ‘Chafont’, take the bridleway hand path around the edge of a small on the left along the edge of the field. wood, through a wooden kissing gate and Continue past the end of the field and, onto a lane. TR and follow the lane for after crossing a bridge, TR. Follow the approx 400m. stream up to the far corner of the field. TR through a gap in the hedge and take the footpath straight ahead along the edge of 4 At the corner TL, ignoring the North Leigh Common. Wychwood Way waymark, and follow the 5 path between electric stock fences across the next field, before continuing along the 7 At a waymark post TL, and follow a well edge of a wood to a kissing gate. defined path for approx 120m. At a Continue straight across the next field. T-junction of paths, TL past some small 6 ponds and along some duck boarding to 4 another junction. Here TR and follow the 3 TL and follow the road downhill to a path straight ahead (crossing a concrete junction. Take the footpath straight ahead 7 footpath), to emerge onto an area of open for approx 600m as it winds between grassland. -

Members of West Oxfordshire District Council 1997/98

MEMBERS OF THE COUNCIL 2020/2021 (see Notes at end of document) FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT COUNCILLORS SEE www.westoxon.gov.uk/councillors Councillor Name & Address Ward and Parishes Term Party Expires ACOCK, JAKE 16 Hewitts Close, Leafield, Ascott and Shipton 2022 Oxon, OX29 9QN (Parishes: Ascott under Mob: 07582 379760 Wychwood; Shipton under Liberal Democrat Wychwood; Lyneham) [email protected] AITMAN, JOY *** 98 Eton Close, Witney, Witney East 2023 Oxon, OX28 3GB Labour (Parish: Witney East) Mob: 07977 447316 (N) [email protected] AL-YOUSUF, Bridleway End, The Green, Freeland and Hanborough 2021 ALAA ** Freeland, Oxon, (Parishes: Freeland; OX29 8AP Hanborough) Tel: 01993 880689 Conservative Mob: 07768 898914 [email protected] ASHBOURNE, 29 Moorland Road, Witney, Witney Central 2023 LUCI ** Oxon, OX28 6LS (Parish: Witney Central) (N) Mob: 07984 451805 Labour and Co- [email protected] operative BEANEY, 1 Wychwood Drive, Kingham, Rollright and 2023 ANDREW ** Milton under Wychwood, Enstone Oxon, OX7 6JA (Parishes: Enstone; Great Tew; Tel: 01993 832039 Swerford; Over Norton; Conservative [email protected] Kingham; Rollright; Salford; Heythrop; Chastleton; Cornwell; Little Tew) BISHOP, Glenrise, Churchfields, Stonesfield and Tackley 2021 RICHARD ** Stonesfield, Oxon, OX29 8PP (Parishes: Combe; Stonesfield; Tel: 01993 891414 Tackley; Wootton; Glympton; Mob: 07557 145010 Kiddington with Asterleigh; Conservative [email protected] Rousham) BOLGER, ROSA c/o Council Offices, -

Cake & Cockhorse

CAKE & COCKHORSE BANBURY HISTORICAL SOCIETY SUMMER 1979. PRICE 50p. ISSN 0522-0823 BANBURY HISTORICAL SOCIETY President: The Lord Saye and Sele chairman: Alan Donaldson, 2 Church Close, Adderbury, Banbury. Magazine Editor: D. E. M. Fiennes, Woadmill Farm, Broughton, Banbury. Hon. Secretary: Hon. Treasurer: Mrs N.M. Clifton Mr G. de C. Parmiter, Senendone House The Halt, Shenington, Banbury. Hanwell, Banbury.: (Tel. Edge Hill 262) (Tel. Wroxton St. Mary 545) Hm. Membership Secretary: Records Series Editor: Mrs Sarah Gosling, B.A., Dip. Archaeol. J.S. W. Gibson, F.S.A., Banbury Museum, 11 Westgate, Marlborough Road. Chichester PO19 3ET. (Tel: Banbury 2282) (Tel: Chichester 84048) Hon. Archaeological Adviser: J.H. Fearon, B.Sc., Fleece Cottage, Bodicote, Banbury. committee Members: Dr. E. Asser, Mr. J.B. Barbour, Miss C.G. Bloxham, Mrs. G. W. Brinkworth, B.A., David Smith, LL.B, Miss F.M. Stanton Details about the Society’s activities and publications can be found on the inside back cover Our cover illustration is the portrait of George Fox by Chinn from The Story of Quakerism by Elizabeth B. Emmott, London (1908). CAKE & COCKHORSE The Magazine of the Banbury Historical Society. Issued three times a year. Volume 7 Number 9 Summer 1979 Barrie Trinder The Origins of Quakerism in Banbury 2 63 B.K. Lucas Banbury - Trees or Trade ? 270 Dorothy Grimes Dialect in the Banbury Area 2 73 r Annual Report 282 Book Reviews 283 List of Members 281 Annual Accounts 2 92 Our main articles deal with the origins of Quakerism in Banbury and with dialect in the Ranbury area. -

The Warriner School

The Warriner School PLEASE CAN YOU ENSURE THAT ALL STUDENTS ARRIVE 5 MINUTES PRIOR TO THE DEPARTURE TIME ON ALL ROUTES From 15th September- Warriner will be doing an earlier finish every other Weds finishing at 14:20 rather than 15:00 Mon - Fri 1-WA02 No. of Seats AM PM Every other Wed 53 Sibford Gower - School 07:48 15:27 14:47 Burdrop - Shepherds Close 07:50 15:25 14:45 Sibford Ferris - Friends School 07:53 15:22 14:42 Swalcliffe - Church 07:58 15:17 14:37 Tadmarton - Main Street Bus Stop 08:00 15:15 14:35 Lower Tadmarton - Cross Roads 08:00 15:15 14:35 Warriner School 08:10 15:00 14:20 Heyfordian Travel 01869 241500 [email protected] 1-WA03/1-WA11 To be operated using one vehicle in the morning and two vehicles in the afternoon Mon - Fri 1-WA03 No. of Seats AM PM Every other Wed 57 Hempton - St. John's Way 07:45 15:27 14:42 Hempton - Chapel 07:45 15:27 14:42 Barford St. Michael - Townsend 07:50 15:22 14:37 Barford St. John - Farm on the left (Street Farm) 07:52 15:20 14:35 Barford St. John - Sunnyside Houses (OX15 0PP) 07:53 15:20 14:35 Warriner School 08:10 15:00 14:20 Mon - Fri 1-WA11 No. of Seats AM PM Every other Wed 30 Barford St. John 08:20 15:35 15:35 Barford St. Michael - Lower Street (p.m.) 15:31 15:31 Barford St. -

Local Election Candidates 2016 Full List

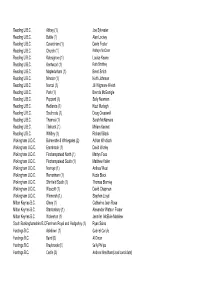

Reading U.B.C. Abbey (1) Joe Sylvester Reading U.B.C. Battle (1) Alan Lockey Reading U.B.C. Caversham (1) David Foster Reading U.B.C. Church (1) Kathryn McCann Reading U.B.C. Katesgrove (1) Louise Keane Reading U.B.C. Kentwood (1) Ruth Shaffrey Reading U.B.C. Mapledurham (1) Brent Smith Reading U.B.C. Minster (1) Keith Johnson Reading U.B.C. Norcot (1) Jill Wigmore-Welsh Reading U.B.C. Park (1) Brenda McGonigle Reading U.B.C. Peppard (1) Sally Newman Reading U.B.C. Redlands (1) Kizzi Murtagh Reading U.B.C. Southcote (1) Doug Cresswell Reading U.B.C. Thames (1) Sarah McNamara Reading U.B.C. Tilehurst (1) Miriam Kennet Reading U.B.C. Whitley (1) Richard Black Wokingham U.D.C. Bulmershe & Whitegates (2) Adrian Windisch Wokingham U.D.C. Emmbrook (1) David Worley Wokingham U.D.C. Finchampstead North (1) Martyn Foss Wokingham U.D.C. Finchampstead South (1) Matthew Valler Wokingham U.D.C. Norreys (1) Anthea West Wokingham U.D.C. Remenham (1) Kezia Black Wokingham U.D.C. Shinfield South (1) Thomas Blomley Wokingham U.D.C. Wescott (1) David Chapman Wokingham U.D.C. Winnersh (1) Stephen Lloyd Milton Keynes B.C. Olney (1) Catherine Jean Rose Milton Keynes B.C. Stantonbury (1) Alexander Watson Fraser Milton Keynes B.C. Wolverton (1) Jennifer McElvie Marklew South Buckinghamshire B.C.Farnham Royal and Hedgerley (1) Ryan Sains Hastings B.C. Ashdown (1) Gabriel Carlyle Hastings B.C. Baird (1) Al Dixon Hastings B.C. -

Ashmolean Museum, See Oxford, University Ashridge College

Index Abingdon lormc.:ri) Bnks .• 3, II, 17. 280, '~13, A!)hmolC'JIl ~Iu~(·um. 1ft Oxford. univ('I'\lty 322 \'hrid~(' Coli<'~(' 8UCk.Il.1, 242.254.26+ "blx", 163, 165 \'''hall. 212 ('a;tulan. I til manor. 2·1I "2 olM'dit'ntiaN, 16) ~t. ~i(hol.l church, 2~1 67 \,h, ilk. I. 13, I.>., 17.85.311.316 17 rhapd' Barton Court hmll. 3, 8, 16 17 Com\\.tJl ('hantry. 2-11 67 Bath Sm'C't, 176 St. \IM'Y and St Katherin('.24-1 :2 CW\.. T1 publi( hClU'oC' 163. 178 rb.10ralion, 2-t2n Oal'" B.lIlk3, R "'hall L.<i~h. H2 ~tr . Warnck'" .\on" hUld, 163. 178 •\'ton Rowant. nil Olk hriclgl', Ili3 •~ lrop :\orthallb .. 68 Oc·k Sln'('t. t.'x('a\.lIions at. 163 78 "ur\"("\ 155+, 16.1. 176 Bakt-r Sir Ih·ri>c:n. architect. 28; 9;.300 I, Inrupp. 313 303. 'IOa romkin" alm .. hou'it.... , 163 l>.lking, Itt trad(" .. \,inc.. yard, 16.j. 171. 176 7 Ball.lnt, ,\dolphu ... 322 Wyndyk(, Furlong, 9111 B"mplOn, 270. 28 I, 285 Abingdon. rarls ur, Iff Bertie Banbury. 1)111, 276, 281, 281. 323 Addabury. 24-8. 259. 276. 279. 281 Britannia Buildings. 323 atriaJ photograph\" 2. 1 S. 83 P.u'llon\ Slr('('t. 323 .\"h,lr<d. 138. 140 I Banoro So. ~ I irhad . 281 •\ga>. R.llpho Bamf'tt. T.G., 311 m"p 1578), 137. 112. 151 Barnoldbv-it'-B(,t'k Lines." 25b" .\.11"<. ~ I akolm. 27.> Barrow II ills. -

Oxfordshire Early Years Provider Directory

Oxfordshire Early Years Provider Directory The following list gives you contact details of providers currently registered to offer the nursery education funding entitlement in your local area. Please contact these providers direct to enquire if they have places available, and for more information on session times and lengths. Private, voluntary and independent providers will also be able to tell you how they operate the entitlement, and give you more information about any additional costs over and above the basic grant entitlement of 15 hours per week. Admissions for Local Authority (LA) school and nursery places for three and four year olds are handled by the nursery or school. Nursery Education Funding Team Contact information for general queries relating to the entitlement: Telephone 01865 815765 Email [email protected] Oxfordshire Early Years Provider Directory Name Telephone Address Independent Windrush Valley School 01993831793 The Green, 2 London Lane, Ascott-under-wychwood, Chipping Norton, OX7 6AN Oxfordshire Early Years Provider Directory Name Telephone Address LEA Nursery, Primary or Special School Wychwood Church of England 01993 830059 Milton Road, Shipton-under-Wychwood, Chipping Primary School Norton, OX7 6BD Woodstock Church of England 01993 812209 Shipton Road, Woodstock, OX20 1LL Primary School Wood Green School 01993 702355 Woodstock Road, Witney, OX28 1DX Witney Community Primary 01993 702388 Hailey Road, Witney, OX28 1HL School William Fletcher Primary School 01865 372301 RUTTEN LANE, YARNTON, KIDLINGTON, OX5 1LW West Witney Primary School 01993 706249 Edington Road, Witney, OX28 5FZ Tower Hill School 01993 702599 Moor Avenue, Witney, OX28 6NB The Marlborough Church of 01993 811431 Shipton Road, Woodstock, OX20 1LP England School The Henry Box School 01993 703955 Church Green, Witney, OX28 4AX The Blake CofE (Aided) Primary 01993 702840 Cogges Hill Road, Witney, OX28 3FR School The Batt CofE (A) Primary 01993 702392 Marlborough Lane, Witney, OX28 6DY School, Witney Tackley Church of England 01869 331327 42 ST.