Ragtime and the Music Oj Charles Ives Judith Tick

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is Jazz? Concert on April 15, 2020 Symphony of Southeast Texas

Exploring American Music: What Is Jazz? Concert on April 15, 2020 Symphony of Southeast Texas Table of Contents Acknowledgement of the Symphony League 1 History of the SOST 2 What is an Orchestra? 3 Who is the Conductor? 4 Audience Etiquette 5 Exploring American Music—What Is Jazz?: An Overview 6 Exploring American Music—What Is Jazz?: Repertoire Duke Ellington (1899–1974): “It Don’t Mean Thing” 9 Scott Joplin (c. 1867–1917): “The Ragtime Dance” 11 Dr. Tim Dueppen: What Is Improvisation? 13 George Gershwin (1898-1937): “Summertime” from Porgy and Bess 15 Joseph Haydn (1732-1809): Concerto for Piano [Soloist: Seth Weeks] 17 Satchmo! A Tribute to Louis Armstrong: arr. Ted Ricketts 19 “A Salute to the Big Bands”: arr. Custer 21 My Concert Journal 23 Musical Terms 24 About the Teacher’s Guide 25 0 Exploring American Music: What Is Jazz? Concert on April 15, 2020 Symphony of Southeast Texas Acknowledgement of the Symphony League of Beaumont In 1955 a group of dedicated symphony supporters formed the Beaumont Symphony Women’s League Inc. Although the name changed in 1993 to the Symphony League of Beaumont, the purpose and commitment remain the same. The League’s mission is to support and promote the growth of the Symphony of Southeast Texas (SOST) and to foster and encourage musical education, participation, and appreciation of the membership and the general public. This organization provides generous financial support and essential services to the orchestra. Their annual String Competition, Youth Guild, Symphony Belles debutante program, and Junior Escorts encourage future generations of musicians, music lovers, and Symphony supporters. -

2018-Wcrsf-Program Web-Version.Pdf

How You Can Help with WCRS contact info ...............2 Message from the WCRS President ............................3 WCRS Board of Directors ...........................................4 Program Editors .........................................................4 WCRS Volunteer Coordinators ...................................4 Festival Volunteers ..................................................... 5 West Coast Ragtime Society Members ........................6 Sacramento Ragtime Society ......................................7 Thanks to Our Donors ........................................... 8–9 WCRS Youth Ragtime Piano Competition ........... 10–11 Ragtime Store ..........................................................12 Recording Policy ....................................................... 12 Food ........................................................................ 13 Seminars ........................................................... 14–16 Special Events ....................................................18–25 Other Festival Features .......................................26-27 Theme Sets by Various Performers .....................28–34 Performers, Presenters and Dance Instructors ..........36 Festival Performers ............................................ 37–81 Venue Map ..............................................................40 Schedule ............................................................ 41–43 Piano Tuning ............................................................ 81 In Memoriam .....................................................82–83 -

Bethena Scott Joplins Ragtime Waltz for Viola Ensemble Sheet Music

Bethena Scott Joplins Ragtime Waltz For Viola Ensemble Sheet Music Download bethena scott joplins ragtime waltz for viola ensemble sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 6 pages partial preview of bethena scott joplins ragtime waltz for viola ensemble sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 3312 times and last read at 2021-09-27 13:14:50. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of bethena scott joplins ragtime waltz for viola ensemble you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Viola Ensemble: Mixed Level: Early Intermediate [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Scott Joplins Bethena Scott Joplins Bethena sheet music has been read 3246 times. Scott joplins bethena arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-27 23:50:44. [ Read More ] Three Ragtime Waltzes By Scott Joplin Bethena Binks Waltz Pleasant Moments Piano Solo Three Ragtime Waltzes By Scott Joplin Bethena Binks Waltz Pleasant Moments Piano Solo sheet music has been read 2443 times. Three ragtime waltzes by scott joplin bethena binks waltz pleasant moments piano solo arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-27 03:27:55. [ Read More ] Scott Joplin Bethena A Concert Waltz Waltz 1905 Arranged For Flute String Trio Scott Joplin Bethena A Concert Waltz Waltz 1905 Arranged For Flute String Trio sheet music has been read 5930 times. Scott joplin bethena a concert waltz waltz 1905 arranged for flute string trio arrangement is for Advanced level. -

Summerfest Theatre James K

EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY THEATRE presents Doudna Fine Arts Center PLAYBILL '95 College of Arts and Humanities SummerFest Theatre James K. Johnson, Dean presents University Theatre Staff Professors Clarence P. Blanchette Jerry D. Eisenhour E.T. Guidotti, Chair David L. Jorns Associate Professors Majorie A. Duehmig David W. Wolski Instructors Karen A. Maim Jean K. Wolski Mary E. Yarbrough Academic Support Professional J. Sain Directed and Staged by Jerry Eisenhour Specialist Musical Direction by James G. Pierson Kevin Cranston Choreography by A Theatre Arts M~or is resident at EIU Jacqueline Bennett which includes specializations in performance, design, and literature and directing Scenery Design by James G. Pierson For those interested, (under the supervision of C.P. Blanchette)* a teacher certification option is available. Costume Design by For additional information see Jerry Eisenhour (3219) Karen Maim or E.T. Guidotti (3121) or visit the main office, FAT 105. Lighting Design by Brandon Hoefle EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY THEATRE Executive Director is a member of the Illinois Theatre Association, E.T. Guidotti the American Alliance for Theatre and Education, and the Association for Theatre in Higher Education, Producer/Company Manager J. Sain the New England Theatre Conference, and the Southwest Theatre Association, Inc. Associate Producer Jerry Eisenhour EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY THEATRE *in partial fullfillment of requirements for is a participant in Region III Independent Study, THA-3500 of the American College Theatre Festival. TINTYPES Conceived by TINTYPES MARY KYTE MUSICAL NUMBERS with ACT ONE MEL MARVIN and GARY PEARLE ARRIVALS Musical & Vocal Arrangements by Mel Marvin Ragtime Nightingale (Joseph F. Lamb, 1915} .................. Charlie & Ensemble Orchestration &Vocal Arrangements by John McKinney The Yankee Doodle Boy (George M. -

AN IN-DEPTH LOOK at SCOTT JOPLIN's TREEMONISHA By

AN IN-DEPTH LOOK AT SCOTT JOPLIN’S TREEMONISHA by Darian M. Clonts Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University December 2020 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Brian Horne, Research Director/Chair ______________________________________ Gary Arvin ______________________________________ Carolyn Calloway-Thomas ______________________________________ Mary Ann Hart September 4, 2020 ii Table of Contents Table of Contents....………………………………………………………………………………iii List of Examples………………………………………………………………………………….iv List of Figures……………………………………………………………………………………..v Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………….1 Chapter I : Scott Joplin’s Early Life and Education………………………………………………8 Chapter II : Scott Joplin and Ragtime……………………………………………………………15 Chapter III : Operas of Scott Joplin and the Story of Treemonisha……………………………...25 Chapter IV : Character and Vocal Analysis of Treemonisha……………………………………34 Chapter V : Musical Analysis of Treemonisha…………………………………………………..50 Chapter VI : Conversation of Authenticity………………………………………………………71 Chapter VII : The Premiere of Treemonisha…………………………………………………….79 Chapter VIII : Houston Grand Opera Production of Treemonisha………………………………87 Chapter IX : Conclusion- Sociological Implications of Treemonisha…………………………...93 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………………108 -

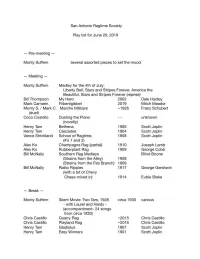

Monty Suffern Several Assorted Pieces to Set the Mood

San Antonio Ragtime Society Play list for June 29, 2019 - Pre-meeting - Monty Suffern several assorted pieces to set the mood -Meeting - Monty Suffern Medley for the 4th of July: Liberty Bell, Stars and Stripes Forever, America the Beautiful, Stars and Stripes Forever (reprise) Bill Thompson My Hero 2002 Dale Hadley Mark Camann Flibertigibbet 2019 Mitch Meador Monty S. I Mark C. Marche Militaire -1826 Franz Schubert (duet) Coco Costello Dusting the Piano unknown (novelty) Henry Tam Beth en a 1905 Scott Joplin Henry Tam Cascades 1904 Scott Joplin Vance Strickland School of Ragtime, 1908 Scott Joplin (#'s 1 and 2) Alex Ko Champagne Rag (partial) 1910 Joseph Lamb Alex Ko Rubberplant Rag 1909 George Cobb Bill McNally Southern Rag Medleys Blind Boone (Strains from the Alley) 1908 (Strains from the Flat Branch) 1909 Bill McNally Rialto Ripples 1917 George Gershwin (with a bit of Chevy Chase mixed in) 191 4 Eubie Blake -Break- Monty Suffern Silent Movie: Two Tars, 1928 circa 1930 various - with Laurel and Hardy - (accompaniment- 24 songs from circa 1930) Chris Castillo Quarry Rag -2015 Chri s Castillo Chris Castillo Playland Rag -2016 Chris Castillo Henry Tam Gladiolus 1907 Scott Joplin Henry Tam Easy Winners 1901 Scott Joplin San Antonio Ragtime Society Meeting: April 27, 2019 List of performers and music played Performer Title Composer Year The Entertainer Weeping Willow The Ragtime Dance Jimmy Drury Scott Joplin The Easy Winners Leola Elite Syncopations Vicki McRae Red Rose Rag Percy Wenrich 1911 Bill Thompson Race Horse Rag Mike Bernard 1911 Vicki McRae & Cleopha - March & Two Step Scott Joplin 1902 Bill Thompson (duet - arr. -

Cast the Band

Award-winning Broadway Musicals Captured LIVE IN PERFORMANCE www.broadwayonline.com Conceived by Mary Kyte with Mel Marvin and Gary Pearle Directed by Gary Pearle Musical Staging by Mary Kyte Performed on Broadway at the John Golden Theatre Directed for Broadway Worldwide by Don Roy King TINTYPES is a charming musical revue focusing on the exciting yet tumultuous period of American history between the turn of CAST the 20th century and the onset of World War I. The score is a Carolyn Mignini blend of patriotic songs, romantic tunes and ragtime by the Lynne Thigpen musical masters of the era, including George M. Cohan, John Trey Wilson Philip Sousa and Scott Joplin. Conceived by Mary Kyte with Mary Catherine Wright Mel Marvin and Gary Pearle, TINTYPES played Broadway’s Jerry Zaks John Golden Theatre in late 1980 through early 1981 and was nominated for three Tony Awards® that year, including Best Musical. THE BAND The cast of five, including Tony Award® winning actress Lynne Mel Marvin, Conductor and Piano Thigpen (An American Daughter) and multi-Tony® winning director Clay Fullum, Assistant Conductor Jerry Zaks (Guys and Dolls, Six Degrees of Separation, Lend Me A Dean Plank,Trombone Tenor,The House of Blue Leaves), portray a variety of characters Jill Jaffe, Violin including hopeful strivers and dream-filled achievers among Daryl Goldberg, Cello the common folk and politician William Jennings Bryan, radical Les Scott,Woodwinds Emma Goldman, inventors Thomas Edison and Henry Ford, among the famous. TINTYPES takes us through a time in our Bruce Doctor, Drums/Percussion nation’s development when the transcontinental railroad and Carnegie Hall were built, electricity and the telephone were introduced to homes, cowboy Theodore Roosevelt became President of the United States and automobiles joined horse- drawn carriages on city streets. -

Classic Ragtime: an Overlooked American Art Form

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity The Expositor: A Journal of Undergraduate Research in the Humanities English Department 2017 Classic Ragtime: An Overlooked American Art Form Daniel Stephens Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/eng_expositor Repository Citation Stephens, D. (2017). Classics ragtime: An overlooked American art form. The Expositor: A Journal of Undergraduate Research in the Humanities, 13, 109-119. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Expositor: A Journal of Undergraduate Research in the Humanities by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 109 Classic Ragtime: An Overlooked American Art Form Daniel Stephens s Nancy Ping-Robbins observed, “Ragtime as a topic of real schol- arly pursuit [was] mostly ignored until the 1980s,” and most sources Apublished prior to that “were originally designed for a general audience.”1 Since Ping-Robbins wrote almost two decades ago, scholarly interest in ragtime has lessened again. This decline is unfortunate, since classic ragtime contains a high degree of complexity, blending the traditions of African American folk songs with the practices of nineteenth-century European music—seen especially in pieces composed by Scott Joplin, inventor and master of the genre—making it a topic rich for critical commentary. However, the genre was poorly received by the classical audiences, due both to its ties to popular music and its roots in African American culture, and it consequently did not receive the attention it deserved. -

Ddd Plays Scott Joplin and J.S. Bach

PLAYS SCOTT JOPLIN AND J.S. BACH WWW.ALBANYRECORDS.COM TROY1163 ALBANY RECORDS U.S. 915 BROADWAY, ALBANY, NY 12207 TEL: 518.436.8814 FAX: 518.436.0643 ALBANY RECORDS U.K. BOX 137, KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA8 0XD TEL: 01539 824008 © 2010 ALBANY RECORDS MADE IN THE USA DDD WARNING: COPYRIGHT SUBSISTS IN ALL RECORDINGS ISSUED UNDER THIS LABEL. Conductor, pianist and educator William Appling was As he intimately explored each composition, Appling was amazed at the complexity of Joplin’s works, his grounded in a traditional European music education, his harmonic genius and exquisite sense of musical balance. The precision of the voicings in several piano works piano teachers claiming direct lineage to Franz Liszt and led him to believe that Joplin had intended them for small musical ensemble. And as Bach and Joplin began Artur Schnabel, and he spent his professional life teaching to demand equal time in Appling’s daily piano work, he soon discovered striking similarities in their music. and conducting the classical repertoire, particularly champi- Though pianists had rarely programmed their works together in recital (and perhaps never before on a record- oning the works of contemporary American composers. ing), he felt the music of each perfectly complemented the other. He was passionate to have people hear that In 1987, a freshman at Western Reserve Academy in the two composers were comparable in the caliber of their work—two geniuses writing at the highest level. Hudson, Ohio, signed up for piano lessons with a heated desire The idea for performances and a recording pairing the music of Scott Joplin and J.S. -

Jazz Fundamentals Chapter 1 Pre-Jazz

Jazz Fundamentals Academy for Lifelong Learning Cape Cod Community College Greg Polanik Spring 2015 Chapter 1 Pre-Jazz Music Links Brass Bands Do Watcha Wanna (homework) Rebirth Brass Band https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3E1VBCcA76E not historically accurate, contains elements of early jazz The Stars and Stripes Forever John Philip Sousa https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a-7XWhyvIpE classic marching band music Ragtime Piano Maple Leaf Rag (homework) Scott Joplin https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pMAtL7n_-rc Left Hand Technique, Ragtime Lesson https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hoRXAporV98 watch: 5:40 - 7:25 - 9:00 The Entertainer Scott Joplin https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fPmruHc4S9Q Swipsey Cakewalk Scott Joplin https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pQnCT9HnMNA a Cakewalk was an exhibition dance, parodying white formal dances The Ragtime Dance Scott Joplin Played by Richard Zimmerman https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GL0GhUMoLg8 { PAGE } Jazz Fundamentals Academy for Lifelong Learning Cape Cod Community College Greg Polanik Spring 2015 The Charleston Rag Eubie Blake https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oQ92_oiVLyk https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R7oQfRGUOnU note the Boogie Woogie bass line, alternating with Ragtime left hand Left Hand Technique, Boogie Woogie Lesson https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7YEl1-0N8d0 Blues Come On In My Kitchen (homework) Robert Johnson https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4up4VP8zjyc folk blues vocal & guitar I Believe I'll Dust My Broom Robert Johnson https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-P4WhmJt9XM Soon One Mornin' Mississippi' Fred -

825646079261.Pdf

SCOTT JOPLIN 1867/8 –1917 All tracks arr. Itzhak Perlman 1 The Ragtime Dance 3.13 2 The Easy Winners 3.11 3 Bethena (a concert waltz) 6.36 4 Magnetic Rag 4.50 5 The Strenuous Life (a ragtime two-step) 3.53 6 The Entertainer 4.11 7 Elite Syncopations 3.14 8 Solace (a Mexican serenade) 7.12 9 Pine Apple Rag 3.10 10 Sugar Cane (a ragtime classic two-step) 3.44 43.19 ITZHAK PERLMAN violin ANDRÉ PREVIN piano 2 Itzhak Perlman Photo: Don Hunstein © Parlophone Records Limited 3 SCOTT JOPLIN: RAGTIMES This album of ragtimes by Scott Joplin, recorded in 1974, was Itzhak Perlman’s first foray beyond the classical repertory, at least on record. The departure proved a successful one and was to be the first of many other such adventures, which also included jazz with André Previn (volume 24) and Oscar Peterson, recordings of Yiddish folk music (volume 38) and film music. In the tradition of his great predecessors, foremost among them Fritz Kreisler and Jascha Heifetz, Perlman supplied the arrangement for violin and piano himself, remaining faithful to the composer’s style while exploiting the classical violin’s rich palette of colours. His partnership with André Previn, who accompanied him on the piano, always retained a classical perspective, while still allowing for a measure of stylistic freedom. As Perlman himself revealed, the ornamentations added by the two performers varied from session to session as the pieces were recorded. Ragtime began life as the preserve of the piano, but in Joplin’s time travelling violinists would often join in with string ensembles known as “Serenaders”, made up of violinists, guitarists, mandolin players and double bassists. -

Table of Contents Is Interactive

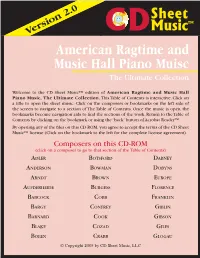

Sheet TM Version 2.0 CDMusic 1 American Ragtime and Music Hall Piano Muisc The Ultimate Collection Welcome to the CD Sheet Music™ edition of American Ragtime and Music Hall Piano Music, The Ultimate Collection. This Table of Contents is interactive. Click on a title to open the sheet music. Click on the composers or bookmarks on the left side of the screen to navigate to a section of The Table of Contents. Once the music is open, the bookmarks become navigation aids to find the sections of the work. Return to the Table of Contents by clicking on the bookmark or using the “back” button of Acrobat Reader™. By opening any of the files on this CD-ROM, you agree to accept the terms of the CD Sheet Music™ license (Click on the bookmark to the left for the complete license agreement). Composers on this CD-ROM (click on a composer to go to that section of the Table of Contents) ADLER BOTSFORD DABNEY ANDERSON BOWMAN DOBYNS ARNDT BROWN EUROPE AUFDERHEIDE BURGESS FLORENCE BABCOCK COBB FRANKLIN BARGY CONFREY GIBLIN BARNARD COOK GIBSON BLAKE COZAD GILES BOLEN CRABB GLOGAU © Copyright 2005 by CD Sheet Music, LLC Sheet TM Version 2.0 CDMusic 2 GUY MACEACHRON SEYMOUR HAHN MAGGIO SILBERBERG HENRICH MARSHALL SILVERMAN AND WARD HOFFMAN MATTHEWS SIMON HUMFELD MCFADDEN SMITH HUNTER MILLS SNYDER INGRAHAM MORRISON STARK JANZA NIEBERGALL STONE JENTES NORTHUP THANE JOHNSON O’HARE THOMPSON JOPLIN POWELL TIERNEY JORDAN PRATT TURPIN KAUFMAN PUCK VODERY KLICKMANN ROBERTS VON TILZER KRELL ROBINSON WENRICH LA ROCCA RUDISILL WHITE LAMB RUSSELL WOODS LAMPE SCHEU WOOLFORD LENZBERG SCHWARTZ WOOLSEY LODGE SCOTT LYONS AND YOSCO SEVERIN The complete Table of Contents begins on the next page Sheet TM Version 2.0 CDMusic 3 BERNARD ADLER GEORGE BOTSFORD Dat Lovin’ Rag (Two Step) Chatterbox Rag The Grizzly Bear (Rag) WILLIE ANDERSON Keystone Rag (Rag) EUDAY L.