Chapter 2 Forgotten History Lessons, Delhi's Missed Date with Water

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adv. No. 12/2019, Cat No. 65, Junior Programer, SKIL DEVELOPMENT and INDUSTRIAL TRAINING DEPARTMENT, HARYANA Evening Session

Adv. No. 12/2019, Cat No. 65, Junior Programer, SKIL DEVELOPMENT AND INDUSTRIAL TRAINING DEPARTMENT, HARYANA Evening Session Q1. A. B. C. D. Q2. A. B. C. D. Q3. A. B. C. D. Q4. A. B. C. D. Q5. A. B. C. D. February 23, 2020 Page 1 of 26 Adv. No. 12/2019, Cat No. 65, Junior Programer, SKIL DEVELOPMENT AND INDUSTRIAL TRAINING DEPARTMENT, HARYANA Evening Session Q6. __________ is the synonym of "JOIN." A. Release B. Attach C. Disconnect D. Detach Q7. __________ is the antonym of "SYMPATHETIC." A. Insensitive B. Thoughtful C. Caring D. Compassionate Q8. Identify the meaning of the idiom "Miss the boat." A. Let too much time go by to complete a task. B. Long for something that you don't have. C. Miss out on an opportunity. D. Not know the difference between right and wrong. Q9. The sentence has an incorrect phrase, which is in bold and underlined. Select the option that is the correct phrase to be replaced so that the statement is grammatically correct. "I train to be a pilot because my dream is to join the Air Force." A. am training B. would train C. are training D. will have trained Q10. Complete the sentence by choosing the correct form of the verb given in brackets. I was very grateful that he _____ (repair) my computer so promptly. A. repairs B. will be repairing C. will repair D. repaired Q11. Which was the capital of Ashoka's empire? A. Ujjain B. Taxila C. Indraprastha D. Pataliputra February 23, 2020 Page 2 of 26 Adv. -

JOURNEY SO FAR of the River Drain Towards East Water

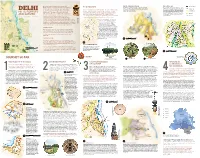

n a fast growing city, the place of nature is very DELHI WITH ITS GEOGRAPHICAL DIVISIONS DELHI MASTER PLAN 1962 THE REGION PROTECTED FOREST Ichallenging. On one hand, it forms the core framework Based on the geology and the geomorphology, the region of the city of Delhi The first ever Master plan for an Indian city after independence based on which the city develops while on the other can be broadly divided into four parts - Kohi (hills) which comprises the hills of envisioned the city with a green infrastructure of hierarchal open REGIONAL PARK Spurs of Aravalli (known as Ridge in Delhi)—the oldest fold mountains Aravalli, Bangar (main land), Khadar (sandy alluvium) along the river Yamuna spaces which were multi functional – Regional parks, Protected DELHI hand, it faces serious challenges in the realm of urban and Dabar (low lying area/ flood plains). greens, Heritage greens, and District parks and Neighborhood CULTIVATED LAND in India—and river Yamuna—a tributary of river Ganga—are two development. The research document attempts to parks. It also included the settlement of East Delhi in its purview. HILLS, FORESTS natural features which frame the triangular alluvial region. While construct a perspective to recognize the role and value Moreover the plan also suggested various conservation measures GREENBELT there was a scattering of settlements in the region, the urban and buffer zones for the protection of river Yamuna, its flood AND A RIVER of nature in making our cities more livable. On the way, settlements of Delhi developed, more profoundly, around the eleventh plains and Ridge forest. -

Hydrogeological Characterization and Assessment of Groundwater Quality in Shallow Aquifers in Vicinity of Najafgarh Drain of NCT Delhi

Hydrogeological characterization and assessment of groundwater quality in shallow aquifers in vicinity of Najafgarh drain of NCT Delhi Shashank Shekhar and Aditya Sarkar Department of Geology, University of Delhi, Delhi 110 007, India. ∗Corresponding author. e-mail: [email protected] Najafgarh drain is the biggest drain in Delhi and contributes about 60% of the total wastewater that gets discharged from Delhi into river Yamuna. The drain traverses a length of 51 km before joining river Yamuna, and is unlined for about 31 km along its initial stretch. In recent times, efforts have been made for limited withdrawal of groundwater from shallow aquifers in close vicinity of Najafgarh drain coupled with artificial recharge of groundwater. In this perspective, assessment of groundwater quality in shallow aquifers in vicinity of the Najafgarh drain of Delhi and hydrogeological characterization of adjacent areas were done. The groundwater quality was examined in perspective of Indian as well as World Health Organization’s drinking water standards. The spatial variation in groundwater quality was studied. The linkages between trace element occurrence and hydrochemical facies variation were also established. The shallow groundwater along Najafgarh drain is contaminated in stretches and the area is not suitable for large-scale groundwater development for drinking water purposes. 1. Introduction of this wastewater on the groundwater system is even more profound. There is considerable contam- The National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi ination of groundwater by industrial and domestic (figure 1) is one of the fast growing metropoli- effluents mostly carried through various drains tan cities in the world. It faces a massive problem (Singh 1999). -

On the Brink: Water Governance in the Yamuna River Basin in Haryana By

Water Governance in the Yamuna River Basin in Haryana August 2010 For copies and further information, please contact: PEACE Institute Charitable Trust 178-F, Pocket – 4, Mayur Vihar, Phase I, Delhi – 110 091, India Society for Promotion of Wastelands Development PEACE Institute Charitable Trust P : 91-11-22719005; E : [email protected]; W: www.peaceinst.org Published by PEACE Institute Charitable Trust 178-F, Pocket – 4, Mayur Vihar – I, Delhi – 110 091, INDIA Telefax: 91-11-22719005 Email: [email protected] Web: www.peaceinst.org First Edition, August 2010 © PEACE Institute Charitable Trust Funded by Society for Promotion of Wastelands Development (SPWD) under a Sir Dorabji Tata Trust supported Water Governance Project 14-A, Vishnu Digambar Marg, New Delhi – 110 002, INDIA Phone: 91-11-23236440 Email: [email protected] Web: www.watergovernanceindia.org Designed & Printed by: Kriti Communications Disclaimer PEACE Institute Charitable Trust and Society for Promotion of Wastelands Development (SPWD) cannot be held responsible for errors or consequences arising from the use of information contained in this report. All rights reserved. Information contained in this report may be used freely with due acknowledgement. When I am, U r fine. When I am not, U panic ! When I get frail and sick, U care not ? (I – water) – Manoj Misra This publication is a joint effort of: Amita Bhaduri, Bhim, Hardeep Singh, Manoj Misra, Pushp Jain, Prem Prakash Bhardwaj & All participants at the workshop on ‘Water Governance in Yamuna Basin’ held at Panipat (Haryana) on 26 July 2010 On the Brink... Water Governance in the Yamuna River Basin in Haryana i Acknowledgement The roots of this study lie in our research and advocacy work for the river Yamuna under a civil society campaign called ‘Yamuna Jiye Abhiyaan’ which has been an ongoing process for the last three and a half years. -

Phoolwalon Ki Sair.Indd 1 27/07/12 1:21 PM 1

CORONATION To the south of the western gateway is the tomb of Qutb Sahib. was meant for the grave of Bahadur Shah Zafar, who was however PARK It is a simple structure enclosed by wooden railings. The marble exiled after the Mutiny and died in Burma. balustrade surrounding the tomb was added in 1882. The rear wall To the north-east of the palace enclosure lies an exquisite mosque, Phoolwalon was added by Fariduddin Ganj-e-Shakar as a place of prayer. The the Moti Masjid, built in white marble by Bahadur Shah I in the early western wall is decorated with coloured fl oral tiles added by the eighteenth century as a private mosque for the royal family and can be Delhi Metro Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb. approached from the palace dalan as well as from the Dargah Complex. Route 6 ki Sair The screens and the corner gateways in the Dargah Complex were Civil Ho Ho Bus Route built by the Mughal emperor Farrukhsiyar. The mosque of Qutb Lines Heritage Route Sahib, built in mid-sixteenth century by Islam Shah Suri, was later QUTBUDDIN BAKHTIYAR KAKI DARGAH AND ZAFAR added on to by Farrukhsiyar. MAHAL COMPLEX The Dargah of Qutbuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki continues to be a sacred place for the pilgrims of different religions. Every week on Thursday 5 SHAHJAHANABAD Red Fort and Friday qawwali is also performed in the dargah. 5. ZAFAR MAHAL COMPLEX 6 Kotla 9 Connaught Firoz Shah Adjacent to the western gate of the Dargah of Place Jantar Qutbuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki, this complex Mantar 2 7 8 NEW DELHI has various structures built in 3 Route 5 1 Rashtrapati the eighteenth and nineteenth 4 Bhavan Purana century. -

History Preserved in Names: Delhi Urban Toponyms of Perso-Arabic

History preserved in names: Delhi urban toponyms of Perso-Ara bic origin Agnieszka Kuczkiewicz-Fraś Toponyms [from the Greek topos (τόπος) ‘place’ and ónoma (δνομα) ‘name’] are often treated merely as words, or simple signs on geographical maps of various parts of the Earth. How ever, it should be remembered that toponyms are also invaluable elements of a region’s heritage, preserving and revealing differ ent aspects of its history and culture, reflecting patterns of set tlement, exploration, migration, etc. They are named points of reference in the physical as well as civilisational landscape of various areas. Place-names are an important source of information regard ing the people who have inhabited a given area. Such quality results mainly from the fact that the names attached to localities tend to be extremely durable and usually resist replacement, even when the language spoken in the area is itself replaced. The in ternal system of toponyms which is unique for every city, when analysed may give first-rate results in understanding various features, e.g. the original area of the city and its growth, the size and variety of its population, the complicated plan of its markets, 5 8 A g n ie s z k a K u c z k ie w ic z -F r a ś habitations, religious centres, educational and cultural institu tions, cemeteries etc. Toponyms are also very important land-marks of cultural and linguistic contacts of different groups of people. In a city such as Delhi, which for centuries had been conquered and in habited by populaces ethnically and linguistically different, this phenomenon becomes clear with the first glance at the city map. -

Blue Riverriver

Reviving River Yamuna An Actionable Blue Print for a BLUEBLUE RIVERRIVER Edited by PEACE Institute Charitable Trust H.S. Panwar 2009 Reviving River Yamuna An Actionable Blue Print for a BLUE RIVER Edited by H.S. Panwar PEACE Institute Charitable Trust 2009 contents ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................................................................... v PREFACE .................................................................................................................................................... vii CHAPTER 1 Fact File of Yamuna ................................................................................................. 9 A report by CHAPTER 2 Diversion and over Abstraction of Water from the River .............................. 15 PEACE Institute Charitable Trust CHAPTER 3 Unbridled Pollution ................................................................................................ 25 CHAPTER 4 Rampant Encroachment in Flood Plains ............................................................ 29 CHAPTER 5 There is Hope for Yamuna – An Actionable Blue Print for Revival ............ 33 This report is one of the outputs from the Ford Foundation sponsored project titled CHAPTER 6 Yamuna Jiye Abhiyaan - An Example of Civil Society Action .......................... 39 Mainstreaming the river as a popular civil action ‘cause’ through “motivating actions for the revival of the people – river close links as a precursor to citizen’s mandated actions for the revival -

Rejuvenating Yamuna River by Wastewater Treatment and Management

In ternational Journal of Energy and Environmental Science 2020; 5(1): 14-29 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ijees doi: 10.11648/j.ijees.20200501.13 ISSN: 2578-9538 (Print); ISSN: 2578-9546 (Online) Rejuvenating Yamuna River by Wastewater Treatment and Management Natarajan Pachamuthu Muthaiyah Department of Centre for Climate Change, Periyar Maniammai University, Thanjavur, India Email address: To cite this article: Natarajan Pachamuthu Muthaiyah. Rejuvenating Yamuna River by Wastewater Treatment and Management. International Journal of Energy and Environmental Science. Vol. 5, No. 1, 2020, pp. 14-29. doi: 10.11648/j.ijees.20200501.13 Received : July 12, 2020; Accepted : November 13, 2020; Published : MM DD, 2020 Abstract: Yamuna is the most important tributary of Ganga River originating from the Yamunotri glacier of Himalaya, the ‘Asian Water Tower ’. Since Yamuna is fed by the above glacier, the Ganga River supplies water perennially. The catchment area of Yamuna River is 3, 45,848km 2 which is the largest among the other tributaries of Ganga. Surface water resource of the Yamuna River is 61.22km 3 and the net groundwater availability is 45.43km 3. Total sewage generation per annum from domestic and industrial sources in Yamuna River basin is about 9.63km 3. Due to the mixing of the above human influenced sewage, the waterways of this basin are stinking in many reaches and almost dead near Delhi. The pollution loads of the stinking and dead reaches of this river pollute the groundwater of the Yamuna River basin in many reaches. To treat and recycle the above sewage load about 1,320 sewage treatment plants are necessary. -

FORTS of INDIA Anurit Vema

FORTS OF INDIA Anurit Vema *'9^7” \ < > k M' . J . i <• : » I : *='>- >.% ' nvjl •I' 4 V FORTS OF INDIA ■ \ f 0i''. ■ V'; ’ V, , ’' I* ;■'; -r^/A ci''> Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2018 with funding from Public.Resource.org https ;//archive.org/details/fortsofindiaOOverm JAMkJ AND KASHMIR FORTS OF INDIA HARIPARBAT "■^Arot kangraW ( HIMACHAL\ ( .' V.PRADESH\ r PUNJAB S', i /kalibangM ■'HARYANA > ARUNACHAL PRADESH ®BIKANER \ A/ D. AMBEr'f-X UTTAR PRADESH^-'... ® RAJASTHAN ® X BHUTAN "'^JAISALMER BHARATPUR’^A--^,@i®/lGPA JODHPUR /^^f^ji^^i^gff^j^^®^ BWALIOR J ALLAHABAD ROHTASGARH MEGHALAYA 'KUMBHALGARH % (\ \ ®\ .0 n.1 , ^•‘-fCHUHAR BANGLADESH TRIPURA f AHtAADABAD ■> WEST C !■ r'^' BENGALI, ® .^XHAMPANIR MADHYA PRADESH FORT WILLIAM A RAT /rOABHOlV ®MANDU BURMA DAULATABAD MAHARASHTRA ^AHMEDNABAR SHJVNER ARABIAN SEA mSINHGARH l\i,' WARANGAL 1, bay of BENGAL RAIGARH . /“ < GULBARGA GOLKUNOA PANHALA BIJAPUR JANDHRA PRADESH VUAYANAGAR iKARNATAKA| '^RJRANGAPATAM m GINGEEi LAKSHADWEEP (INDIA) SRI \ INDIAN OCEAN LANKA 6aMd upon Survey ol India outline map printed in 1980 The territorial waters of India extend into the sea to a distance of twelve nautical miles measured from the appropriate base line. ) Government of India copyrliht. The twundary of Meghalaya shown on this map is as interpreted from the Nonh-Eestern Areas (Reorgamaaiion) Act, 1971. but has yet to be venlied 49 FORTS OF INDIA AMRIT VERMA PUBLICATIONS DIVISION MINISTRY OF INFORMATION AND BROADCASTING GOVERNMENT OF INDIA May 1985 {Jyaistha 1907) ® Publications Division Price -

Case Study of Najafgarh Drain

Case study of Najafgarh Drain - A rich wetland ecosystemin Delhi turning into a highly polluted water body Dr.Nibedita Khuntia*, Esha Govil**, Vikas** and Cessna Sahu** *Assistant Professor, Department of Biology, ** B. Tech, Department of Computer Science– Maharaja Agrasen College, Universityof Delhi Abstract Over the past years due to rigorous agricultural practice, urbanization,rapid industrialization and daily household activities, water pollution has becomea major issue. These factors have played havoc on a water body in the national capital of India as well.The famous Najafgarh Drain in Delhi, once a rich wetland,has turned into one of the most polluted water body in the country. This paper discusses the ecological importance of the drain, the causes and effects of the subsequent decline in its quality. It also discusses the findings of two field visits undertaken to understand the local effects of water pollution of the drain on the lives of residents who live in proximity of the drain. Keywords: Najafgarh Drain, pollution loads, industrialization, urbanization, sewage disposal, environmental degradation Introduction: The famous Najafgarh drain (See Map in Figure 1) in the national capital of the country got its name from a town called Najafgarh in South West Delhi. It is now recognized as the “Ganda Nallah” by the residents of the city due to high levels of pollution. The situation is so bad, that in 2005, the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) stamped it as a highly polluted drain and put it under “D” category with other 13 highly polluted wetlands(7). This wasn't always the state of the drain. -

Irrigation and Flood Control

IRRIGATION AND FLOOD CONTROL INTRODUCTION Irrigation & Flood Control Department is entrusted with the responsibility of providing irrigation facilities to the farmers of rural villages of Delhi through Effluent received from Sewage Treatment Plant as well as through a Network of State tube-wells available in the rural areas, maintaining the embankments constructed along on bothsides of river Yamuna in the jurisdiction of Govt. of NCT of Delhi, maintenance of 63 Nos. storm water drains in the various Districts of Govt. of NCT of Delhi e.g, Supplementary drain, Najafgarh Drain, Trunk Drain No.I & Trunk Drain No. II, Gazipur Drain, Pankha Road Drain, Palam Drain, Nasirpur Drain, Mungeshpur Drain, Nangloi Drain etc., including construction of bridges over these drains. Besides this, Irrigation & Flood Control Deptt. is also equipped with machinery such as draglines, bulldozers, dredger and heavy duty electrical and diesel pump sets which are utilized for removal of drainage congestion during monsoon from low lying areas. FUNCTIONS AND ACTIVITIES OF THE DEPTT. 1. Protecting the city of Delhi from floods in River Yamuna, by construction, strengthening and maintenance of marginal embankments including planning execution and maintenance of flood protection & river training works 2. Protecting the city of Delhi against floods in Sahibi Nadi- Najafgarh Nallah basin by maintenance of Dhansa Bund, Najafgarh drain and construction of a new drain, called Supplementary Drain. 3. To provide drainage to Delhi area through various trunk storm-water drains having more than 1000 cusecs capacity. 4. Effective monitoring of the flood situation in the river basin during the floods and to take all precautionary/preventive measures to avoid any untoward situation including emergent flood protection/flood fighting measures, if such a situation arises. -

Answered On:22.12.2003 Protection of Monument A.F

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA TOURISM AND CULTURE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:3013 ANSWERED ON:22.12.2003 PROTECTION OF MONUMENT A.F. GOLAM OSMANI Will the Minister of TOURISM AND CULTURE be pleased to state: (a) the details of heritage monuments at Mehrauli included in the list of protected monuments; (b) the details of monuments there which are not yet protected by ASI; ( (c) whether a new heritage site has been identified for protection in Mehrauli: (d) If so, whether any private land or buildings are included in the newly identified site; and (e) If so, the steps taken to remove illegal occupation and construction therefrom? Answer MINISTER FOR TOURISM AND CULTURE (SHRI JAGMOHAN) (a) The list of 24 monuments declared as of national importance under Archaeological Survey of India, in Mehrauli is at Annexure-I. (b) The list of 195 monuments based on the list published by INTACH in Mehrauli which are not yet protected, is at Annexure-II. (c ) Yes, Sir. Lal Kot, Jahanpanah Wall, Balban`s Tomb, unprotected portions of fortification wall of Qila Rai Pithora, Quli-Khan`s Tomb, and monuments/ruined structures located inside the D.D.A. Heritage Park, have been identified for declaration as monuments of national importance. (d) No, Sir. (e) Question does not arise. ANNEXURE-I ANNEXURE REFERRED TO IN REPLY TO PART (a) TO THE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO.3013 FOR 22.12.2003 LIST OF MONUMENTS UNDER CENTRAL PROTECTION IN MEHRAULI, DELHI 1. Bastion where a wall Jahan Panah meets the wall of Rai Pithora Fort 2. Ramp and Gateway of Rai Pithor`s Fort 3.