That's Why She Fell for the Leader of the Pack

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BUSINESS 1964 Review 1965 Preview

DECEMBER 31, 1964 -JANUARY 9, 1965-ON SALE TWO WEEKS PRICE THIS ISSUE: 50 CENTS DOUBLE VALUE HOLIDAY ISSUE BUSINESS 1964 Review 1965 Preview The Yearend Awards1964 taw?. OP4PZ VIN1t)81A 1S3m Atlyfi N0130N18d A3xViv*V 1301N 3 413 S- 111111111t.t. "FANCY PANTS,"AL HIRT'S SWINGING NEW SINGLE SERVED UP IN HIS HONEY HORN STYLE Vw "STAR DUST." -8487 -0iiiCk VICIORCO- @The most trusted name in sound .110116_ grftil Illemene 3" 91101 Ammer, I1166 REVIEWOF THEWEEK Epic's GreatYear Victor Gets "Sound" cert dates in Spain,Italy, Ger- V.ctor Records landeda hotmany and Sweden. The taken and dosome more ix _ne last week, the sound ist wound up his pian-cording with them. Soif any of the upcoming track tour last Sat- film versionurday (19) witha concert inone knows where toreach th of Rodgers and Brussels. James Gang, callUnited Art Hammerstein's ists Records. Phone -The Sound OfMusic." The Garner is planninganother No. is Ci film stars JulieAndrews andtour of Europein late 1965 5-6000. (No gagsplease.) Christopher Plummer.The pic-or early 1966. Hemay tour Screen GemsStreak ture will be premieredin NewSouth Americaand Australia Screen Gems -ColumbiaMu York on March2,1965, andthe first half of1965. While insic is heading intothe home. later that monthwill open inEurope he recordedan albumstretch of 1964 intenton lead. cities throughoutthe land. live in Amsterdamwhich willing the parade ofBMI song As a Broadwaymusical "Thebe issued inEurope by Phil-award winners forthe year. Sound Of Music"sold over aips. American The firm, headedup by Don million copies, rights are not one of the rareyet sewed up.(Line formson Kirshner, has alreadyscored albums ever toreach this fig-the left, and the with a half dozentop ten songs ure. -

Author Surname

Author surname Author first name Title Genre Copies Abercrombie Joe Red country Fantasy 10 Shy South hoped to bury her bloody past and ride away smiling, but she'll have to sharpen up some bad old ways to get her family back, and she's not a woman to flinch from what needs doing. She sets off in pursuit with only a pair of oxen and her cowardly old stepfather Lamb for company. But it turns out Lamb's buried a bloody past of his own. And out of the lawless Far Country the past never stays buried. Ackroyd Peter Hawksmoor Crime 10 Nicholas Dyer, assistant to Sir Christopher Wren and the man with a commission to build seven London churches, plans to conceal a dark secret at the heart of each church. 250 years later, detective Nicholas Hawksmoor is investigating a series of gruesome murders. Ackroyd Peter The Lambs of London Historical 10 Touching and tragic, ingenious, funny and vividly alive, this is Ackroyd at the top of his form in a masterly retelling of a 19th century drama which keeps the reader guessing right to the end. Adichie Chimamanda Ngozi Americanah General 10 From the award winning author of Half of a Yellow Sun', a powerful story of love, race and identity. As teenagers in Lagos, Ifemelu and Obinze fall in love. Their Nigeria is under military dictatorship, and people are fleeing the country if they can. The self-assured Ifemelu departs for America. There she suffers defeats and triumphs, finds and loses relationships, all the while feeling the weight of something she never thought of back home: race. -

Delicate Affections

DDDDeeeelllliiiiccccaaaatttteeee AAffffffffeeeeccccttttiiiioooonnnnssss by Adrian Saldanha Let me take you away, for a moment, to a place far from here. A lush green forest meadow grows with patches of exquisite wildflowers blossoming everywhere — a veritable paradise on earth. In the middle of it all is a tiny, crystal clear pond that reflects the light that falls on it. The pond isn't very deep, and you can see the assortment of pebbles at the bottom of it. From that pond stems a wandering stream that ventures further into the wilderness. The grass beneath your feet is thick and a very healthy shade of green. The trees are tall and mighty, a worthy inspiration with their vast grandeur, and between some of the high branches, great rays of sunlight manage to shine through into the forest and create a nearly holy and spiritual glow. The very sight of it is so beautiful and soothing; it makes you wonder how some divine force in the universe could not exist. In the morning, you and I are together. The songbirds sing their tunes melodically, as the world gently wakes up. Despite its great solace, however, you and I are too restless. We quickly amuse ourselves by trying to climb the trees, toss pebbles into the pond, and chase one another throughout the wilderness. We haven't a care in the world, and I find myself unable to admire the calmness of meadow, for I am too busy admiring your beauty and your grace, as you're basked in that gentle morning light. My heart races and skips because I know I am in love, though I dare not say a word, for I know not how you feel yourself. -

June Una Voce JOURNAL of the PAPUA NEW GUINEA ASSOCIATION of AUSTRALIA INC

ISSN 1442-6161, PPA 224987/00025 2012, No 2 - June Una Voce JOURNAL OF THE PAPUA NEW GUINEA ASSOCIATION OF AUSTRALIA INC Patrons: Major General Michael Jeffery AC CVO MC (Retd) Mr Fred Kaad OBE Note: Annual Membership List In This Issue is included with this Una Voce. COMPLETE UV AVAILABLE ONLINE 3 * * * PNG…IN THE NEWS 5 CHRISTMAS LUNCHEON – LETTERS TO THE EDITOR 8 This year’s Christmas Luncheon will be NOTES FROM THE N T 10 held on Sunday 2 December at the ANZAC DAY 2012 IN RABAUL 12 Killara Golf Club, 556 Pacific DAWN SERVICE ADDRESS AT RABAUL 14 Highway, Killara (Sydney, NSW.) Keep an eye on the PNGAA Forum: RABAUL CENOTAPH 2012 16 Notebook for further information which AS YOU RIP SO SHALL YOU SEW 17 will also be in the September Una Voce KOKODA: 70 YEARS ON 18 with the booking form. We hope to see PACIFIC ISLANDS EXHIBITION 20 as many there as possible so put the date WATABUNG PRIMARY SCHOOL 21 in your diary NOW!! THE JIMI VALLEY PINE STANDS 23 NEW FACILTY NOW A RAW DEAL 24 AVAILABLE ON THE PNGAA MT GILUWE 26 WEBSITE - PNGAA MEMBERS UP AND DOWN MOUNTAINS 27 ONLY: GLIMMER OF HOPE 28 – Search and retrieve from LETTER by Corporal Llew Pippen 31 archived Una Voces, 1978 to present, DEDICATION OF RABAUL & MONTEVIDEO now available ONLINE. MARU MEMORIAL 32 Please see page 3 INDEXATION UPDATE 33 GIVING THE BAD NEWS 35 GOULBURN ART GALLERY HELP WANTED 36 Visit from Sydney 29 SEP 2012 See page 20. RSVP 15Aug 2012 BOOK REVIEW 36 * * * FRYER PNGAA COLLECTION 38 VISIT TO THE MOUNTAINS WALK INTO PARADISE 41 The annual spring visit to the Blue LLOYD HURRELL 44 Mountains: Thursday 4 October. -

Madonna - 1982 - 2009 : the Lyrics Book - 1 SOMMAIRE

Madonna - 1982 - 2009 : The Lyrics Book - www.madonnalex.net 1 SOMMAIRE P.03 P.21 P.51 P.06 P.26 P.56 P.09 P.28 P.59 P.10 P.35 P.66 P.14 P.40 P.74 P.15 P.42 P.17 P.47 Madonna - 1982 - 2009 : The Lyrics Book - www.madonnalex.net 2 ‘Cause you got the best of me Chorus: Borderline feels like I’m going to lose my mind You just keep on pushing my love over the borderline (repeat chorus again) Keep on pushing me baby Don’t you know you drive me crazy You just keep on pushing my love over the borderline Something in your eyes is makin’ such a fool of me When you hold me in your arms you love me till I just can’t see But then you let me down, when I look around, baby you just can’t be found Stop driving me away, I just wanna stay, There’s something I just got to say Just try to understand, I’ve given all I can, ‘Cause you got the best of me (chorus) Keep on pushing me baby MADONNA / Don’t you know you drive me crazy You just keep on pushing my love over the borderline THE FIRST ALBUM Look what your love has done to me 1982 Come on baby set me free You just keep on pushing my love over the borderline You cause me so much pain, I think I’m going insane What does it take to make you see? LUCKY STAR You just keep on pushing my love over the borderline written by Madonna 5:38 You must be my Lucky Star ‘Cause you shine on me wherever you are I just think of you and I start to glow BURNING UP And I need your light written by Madonna 3:45 Don’t put me off ‘cause I’m on fire And baby you know And I can’t quench my desire Don’t you know that I’m burning -

Punk, Love and Marxism

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 7-11-2016 12:00 AM Bodies: Punk, Love and Marxism Kathryn Grant The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Christopher Keep The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Theory and Criticism A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Kathryn Grant 2016 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Continental Philosophy Commons, Other Music Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons Recommended Citation Grant, Kathryn, "Bodies: Punk, Love and Marxism" (2016). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3935. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3935 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract: This thesis returns love to the purview of Marxism and punk, which had attempted to ban the interpersonal in respective critiques of abstractions. Love-as-sense—as it is figured by Marx— will be distinguished from the love-of-love-songs, and from commodity fetishism and alienation, which relate to this recuperated love qua perception or experience. As its musical output exhibited residue of free love’s failure, and cited sixties pop which characterized love as mutual ownership, American and British punk from 1976-80 will be analyzed for its interrogation of commodified love. An introductory chapter will define love as an aesthetic activity and organize theoretical and musical sources according to the prominence of the body. -

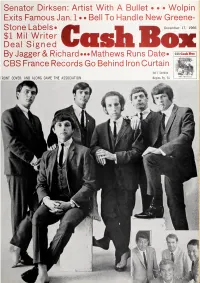

Deal Signed by Jagger& Richard •••Mathews Runs Date* CBS France Records Go Behind Iron Curtain

Senator Dirksen: Artist With A Bullet • • • Wolpin Exits Famous Jan. 1 • • Bell To Handle New Greene- Stone Labels* $1 Mil Writer Deal Signed By Jagger& Richard •••Mathews Runs Date* CBS France Records Go Behind Iron Curtain Int'l Section FRONT COVER: AND ALONG CAME THE ASSOCIATION Begins Pg. 55 p All the dimensions of a#l smash! *smm 1 4-439071 P&ul Revere am The THE single of '66 B THE SPIRIT OP *67 from this brand PAUL REVERE tiIe RAIDERS INCLUDING: HUNGRY THE GREAT AIRPLANE new album— STRIKE GOOD THING LOUISE 1001 ARABIAN NIGHTS CL2595/CS9395 (Stereo) Where the good things are. On COLUMBIA RECORDS ® "COLUMBIA ^MAPCAS REG PRINTED IN U SA GashBim Cash Bock Vol. XXVIII—Number 22 December 17, 1966 (Publication Office) 1780 Broadway New York, N. Y. 10019 (Phone: JUdson 6-2640) CABLE ADDRESS: CASHBOX, N. Y. JOE ORLECK Chairman of the Board GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher NORMAN ORLECK Executive Vice President MARTY OSTROW Vice President LEON SCHUSTER Disk Industry—1966 Treasurer IRV LICHTMAN Editor in Chief EDITORIAL TOM McENTEE Associate Editor RICK BOLSOM ALLAN DALE EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS MIKE MARTUCCI JERRY ORLECK BERNIE BLAKE The past few issues of Cash Box Speaking of deals, 1966 was marked Director Advertising of have told the major story of 1966. by a continuing merger of various in- ^CCOUNT EXECUTIVES While there were other developments dustry factors, not merely on a hori- STAN SO I PER BILL STUPER of considerable importance when the zontal level (label purchases of labels), Hollywood HARVEY GELLER, long-range view is taken into account, but vertical as well (ABC's purchase of ED ADLUM the record business is still a business a wholesaler, New Deal). -

TONY WHYTON Telling Tales: Witnessing and the Jazz Anecdote

The Source: Challenging Jazz Criticism TONY WHYTON Telling tales: witnessing and the jazz anecdote Language as culture is the collective memory bank of a people’s experience in history. Culture is almost indistinguishable from language that makes possible its genesis, growth, banking, articulation and indeed its transmission from one generation to the next. (Thiong’o,1999:289) He lies like an eye-witness… (Volkov, 1981:1) Understanding anecdote The conventional jazz narrative is dominated by mythologies, chronological ‘packaged’ histories, stereotypical imagery and colourful stories that often oversimplify and romanticise issues surrounding the music. Notably, the role of the jazz anecdote is something that forms a part of any jazz musician’s everyday life and yet seems to be the most uncritical of methods used to discuss the music. Anecdote derives from the Greek meaning ‘unpublished’ but, unlike the more fashionable ‘oral history’, the word normally implies an uncritical and less academic approach. Indeed, the semantic connotations of anecdote have allowed it to slip virtually unnoticed, and without critical appraisal, into the canon of jazz history. The boundaries between anecdote and other forms of narrative, such as oral history and testimony, are often blurred; however, I have deliberately chosen to use the term ‘anecdote’ as a descriptor within this article, and all that the term implies, with the aim of raising the semantic stakes. Anecdotal accounts of jazz are an essential ingredient in musicians' interactions and discussions of music. The deeply social nature of the music, its celebrated oral tradition and the obsession with documentation have established anecdotal stories as a primary means of communicating historical information. -

THIRD WAVE FEMINISM in POP MUSIC by THAILAN PHAM

ARTICULATING FEMINISM AND POLITICS: THIRD WAVE FEMINISM IN POP MUSIC by THAILAN PHAM (Under the Direction of Jay Hamilton) ABSTRACT This study examines pop music in context of third wave feminism. The songs selected as material text are: Gretchen Wilson’s “Redneck Woman,” Avril Lavigne’s “Sk8er Boi,” Christina Aguilera’s “Can’t Hold Us Down,” featuring Lil’ Kim, and Missy Elliott’s “Work It.” The songs and corresponding music videos were analyzed for their responses and solutions to the issue of gender inequality. The songs were also examined for contradiction among songs and in relationship to third wave feminism. Results indicated similarities along ethnic lines and visual displays of sexuality rooted in patriarchal gender construction. INDEX WORDS: Pop music, Third wave feminism, Contradiction, Songs, Music videos, Sexuality, Patriarchy ARTICULATING FEMINISM AND POLITICS: THIRD WAVE FEMINISM IN POP MUSIC by THAILAN PHAM B.A., The University of Georgia, 2003 A.B.J., The University of Georgia, 2003 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2005 © 2005 Thailan Pham All Rights Reserved ARTICULATING FEMINISM AND POLITICS: THIRD WAVE FEMINISM IN POP MUSIC by THAILAN PHAM Major Professor: Jay Hamilton Committee: Christine Harold Anandam Kavoori Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia August 2005 DEDICATION For my grandmother Nelle Morgan Burton August 10, 1917 – February 21, 2005 who taught me strength, love, and laughter My parents Dr. An Van Pham and Lienhoa Pham who have always demanded the most and expected absolutely nothing less My brother Binh Pham who has always offered a sympathetic ear and valuable advice even from halfway across the world iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank Dr. -

New York State Stormwater Managment Design Manual

New York State Stormwater Management Design Manual Chapter 5: Green Infrastructure Practices Section 5.1 Planning for Green Infrastructure: Preservation of Natural Features and Conservation Design Chapter 5: Green Infrastructure Practices This Chapter presents planning and design of green infrastructure practices acceptable for runoff reduction. Green infrastructure planning includes measures for preservation of natural features of the site and reduction of proposed impervious cover. The green infrastructure techniques include practices that enable reductions in the calculated runoff from contributing areas and the required water quality volume. Section 5.1 Planning for Green Infrastructure: Preservation of Natural Features and Conservation Design The first step in planning for stormwater management using green infrastructure is to avoid or minimize land disturbance by preserving natural areas. Development should be strategically located based on the location of resource areas and physical conditions at a site. Also, in finalizing construction, soils must be restored to the original properties and according to the intended function of the proposed practices. Preservation of natural features includes techniques to foster the identification and preservation of natural areas that can be used in the protection of water, habitat and vegetative resources. Conservation design includes laying out the elements of a development project in such a way that the site design takes advantage of a site’s natural features, preserves the more sensitive areas and identifies any site constraints and opportunities to prevent or reduce negative effects of development. The techniques covered in this section are listed in Table 5.1. Table 5.1 Planning Practices for Preservation of Natural Features and Conservation Design Practice Description Preservation of Undisturbed Delineate and place into permanent conservation undisturbed forests, native Areas vegetated areas, riparian corridors, wetlands, and natural terrain. -

Pale Fire Quite Simple | Victims the Buck Pets

w/ Cover Page (feed) Æ play dead | pale fire the buck pets | a little murder 12" single from the LP The Buck Pets c. 1985 Clay Records c. 1989 Island Records Play Dead were an English post-punk group from Oxford that The Buck Pets were an American alternative rock band formed grew out of the fading English punk scene in 1980. Though in the late 1980s in Dallas, Texas. While they initially gained a the band was identified with groups like UK Decay and Sex degree of support from Island Records for their first LP, 1989's Gang Children, the band felt they didn't belong under the hard edged The Buck Pets, on the eve of the release of their gothic title. The band made three studio albums for four 2nd LP Mercurotones, Island was bought by PolyGram - the A&R different small labels—Fresh Records, Jungle Records, staff was let go, and projects were shelved while the new Situation 2, and Clay Records—before forming their own owners evaluated their new property. During their short label, Tanz, for their final album, Company Of Justice, tenure, The Buck Pets garnered tour spots with larger acts such which appeared in 1985. as Neil Young (Ragged Glory Tour) and Jane's Addiction, but in the end, they failed to see much commercial success. quite simple | victims crash street kids | little girls 7" Single from the LP Little Girls c. 1982 Fat City Records c. 1987 self-released Endless gigging throughout the Minneapolis area and the Quite Simple was a very short-lived Gothic Rock band from Midwest built this Twin Cities power pop outfit a strong The Netherlands. -

The Vandellas

p r f m Martha and THE VANDELLAS f YOU HAD A p u l s e in the summer of 1964 and heard Martha and Gloria Jean Williamson, with whom she’d sung as the Del-Phis. Reeves’ piercing cry — "Calling out, around the world, are you ready Reeves and her friends became the frisky female chorus you heard behind for a brand-new beat?” — you might have recognized it as the siren Marvin Gaye on many of his early recordings. Backup singers aren’t sup sound of Berry GordyJr.’s Motown Records. When you are inside posed to jump out at you, but once you know it’s Reeves, it’s impossihfe that song, Motown’s Sound of Young America is happening, and to miss her "Hitchhike, baby!” behind Gaye’s lead on "Hitch Hike.” all is well in the world. As Reeves sings, "Summer’s here, and the Inevitably, Reeves and her colleagues were ushered into Gordy’s sec time is right for dancing in the street,” to one of the most irresistible rifeond-floor office and offered a contract The boss gave them 15 minutes IMotown’s Funk Brothers ever concocted, for that moment you are young to pick a new name, and so Reeves, Ashford and Sterling (Williamson and wild and utterly without a care. opted out) became Martha and the Vandellas. Their first record, "Til Such is the enchantment that Martha Reeves and the Vandellas were Have to Let Him Go,” went nowhere, but they soon scored with Hol- able to summon up out of a three-minute pop song - with the help of land-Dozier-Holland’s "Come and Get These Memories,” which Gordy and a fleet of Motown support reached No.