Paradise Lost

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hybrid Variations on a Documentary Theme

Hybrid variations on a documentary theme Robert Stam1 1 É professor transdisciplinar da Universidade de Nova York. Autor de diversos livros sobre cinema e literatura, cinema e estudos culturais, incluindo Brazilian cinema, Reflexivity in film and literature, Subversive pleasure, Tropical multiculturalism, Film theory: an introduction, Literature through film e François Truffaut and friends. Formado pela Universidade da Califórnia, Berkeley, também frequentou a Universidade de Paris III. Lecionou na Tunísia, na França e no Brasil (USP, UFF, UFMG) E-mail: [email protected] revista brasileira de estudos de cinema e audiovisual | julho-dezembro 2013 Resumo ano 2 número 4 Embora muitas vezes encarado como pólos opostos, o documentário e a ficção são, na verdade, teórica e praticamente entrelaçados, assim como a história e a ficção, também convencionalmente definidos como opostos, são simbioticamente ligados. O historiador Hayden White argumentou em seu livro Metahistory que a distinção mito/ história é arbitrária e uma invenção recente. No que diz respeito ao cinema, bem como à escrita, White apontou que pouco importa se o mundo que é transmitido para o leitor/espectador é concebido para ser real ou imaginário, a forma de dar sentido discursivo a ele através do tropos e da montagem do enredo é idêntica (WHITE, 1973). Neste artigo, examinaremos as maneiras que a hibridação entre documentário e ficção tem sido mobilizada como radical recurso estético. Palavras-chave Documentário, ficção, hibridização, sentido discursivo. Abstract Although often assumed to be polar opposites, documentary and fiction are in fact theoretically and practically intermeshed, just as history and fiction, also conventually seen as opposites, are symbiotically connected. -

IN STILL ROOMS CONSTANTINE JONES the Operating System Print//Document

IN STILL ROOMS CONSTANTINE JONES the operating system print//document IN STILL ROOMS ISBN: 978-1-946031-86-0 Library of Congress Control Number: 2020933062 copyright © 2020 by Constantine Jones edited and designed by ELÆ [Lynne DeSilva-Johnson] is released under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non Commercial, No Derivatives) License: its reproduction is encouraged for those who otherwise could not aff ord its purchase in the case of academic, personal, and other creative usage from which no profi t will accrue. Complete rules and restrictions are available at: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ For additional questions regarding reproduction, quotation, or to request a pdf for review contact [email protected] Th is text was set in avenir, minion pro, europa, and OCR standard. Books from Th e Operating System are distributed to the trade via Ingram, with additional production by Spencer Printing, in Honesdale, PA, in the USA. the operating system www.theoperatingsystem.org [email protected] IN STILL ROOMS for my mother & her mother & all the saints Aιωνία η mνήμη — “Eternal be their memory” Greek Orthodox hymn for the dead I N S I D E Dramatis Personae 13 OVERTURE Chorus 14 ACT I Heirloom 17 Chorus 73 Kairos 75 ACT II Mnemosynon 83 Chorus 110 Nostos 113 CODA Memory Eternal 121 * Gratitude Pages 137 Q&A—A Close-Quarters Epic 143 Bio 148 D R A M A T I S P E R S O N A E CHORUS of Southern ghosts in the house ELENI WARREN 35. Mother of twins Effie & Jr.; younger twin sister of Evan Warren EVAN WARREN 35. -

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum Rivette: Texts and Interviews (editor, 1977) Orson Welles: A Critical View, by André Bazin (editor and translator, 1978) Moving Places: A Life in the Movies (1980) Film: The Front Line 1983 (1983) Midnight Movies (with J. Hoberman, 1983) Greed (1991) This Is Orson Welles, by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich (editor, 1992) Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995) Movies as Politics (1997) Another Kind of Independence: Joe Dante and the Roger Corman Class of 1970 (coedited with Bill Krohn, 1999) Dead Man (2000) Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000) Abbas Kiarostami (with Mehrmax Saeed-Vafa, 2003) Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (coedited with Adrian Martin, 2003) Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (2004) Discovering Orson Welles (2007) The Unquiet American: Trangressive Comedies from the U.S. (2009) Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Film Culture in Transition Jonathan Rosenbaum the university of chicago press | chicago and london Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote for many periodicals (including the Village Voice, Sight and Sound, Film Quarterly, and Film Comment) before becoming principal fi lm critic for the Chicago Reader in 1987. Since his retirement from that position in March 2008, he has maintained his own Web site and continued to write for both print and online publications. His many books include four major collections of essays: Placing Movies (California 1995), Movies as Politics (California 1997), Movie Wars (a cappella 2000), and Essential Cinema (Johns Hopkins 2004). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. -

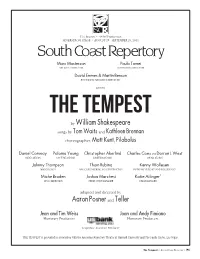

By William Shakespeare Aaron Posner and Teller

51st Season • 483rd Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / AUGUST 29 - SEPTEMBER 28, 2014 Marc Masterson Paula Tomei ARTISTIC DIRECTOR MANAGING DIRECTOR David Emmes & Martin Benson FOUNDING ARTISTIC DIRECTORS presents THE TEMPEST by William Shakespeare songs by Tom Waits and Kathleen Brennan choreographer, Matt Kent, Pilobolus Daniel Conway Paloma Young Christopher Akerlind Charles Coes AND Darron L West SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN Johnny Thompson Thom Rubino Kenny Wollesen MAGIC DESIGN MAGIC ENGINEERING AND CONSTRUCTION INSTRUMENT DESIGN AND WOLLESONICS Miche Braden Joshua Marchesi Katie Ailinger* MUSIC DIRECTION PRODUCTION MANAGER STAGE MANAGER adapted and directed by Aaron Posner and Teller Jean and Tim Weiss Joan and Andy Fimiano Honorary Producers Honorary Producers Corporate Associate Producer THE TEMPEST is presented in association with the American Repertory Theater at Harvard University and The Smith Center, Las Vegas. The Tempest • SOUTH COAST REPERTORY • P1 CAST OF CHARACTERS Prospero, a magician, a father and the true Duke of Milan ............................ Tom Nelis* Miranda, his daughter .......................................................................... Charlotte Graham* Ariel, his spirit servant .................................................................................... Nate Dendy* Caliban, his adopted slave .............................. Zachary Eisenstat*, Manelich Minniefee* Antonio, Prospero’s brother, the usurping Duke of Milan ......................... Louis Butelli* Gonzala, -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

In BLACK CLOCK, Alaska Quarterly Review, the Rattling Wall and Trop, and She Is Co-Organizer of the Griffith Park Storytelling Series

BLACK CLOCK no. 20 SPRING/SUMMER 2015 2 EDITOR Steve Erickson SENIOR EDITOR Bruce Bauman MANAGING EDITOR Orli Low ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR Joe Milazzo PRODUCTION EDITOR Anne-Marie Kinney POETRY EDITOR Arielle Greenberg SENIOR ASSOCIATE EDITOR Emma Kemp ASSOCIATE EDITORS Lauren Artiles • Anna Cruze • Regine Darius • Mychal Schillaci • T.M. Semrad EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Quinn Gancedo • Jonathan Goodnick • Lauren Schmidt Jasmine Stein • Daniel Warren • Jacqueline Young COMMUNICATIONS EDITOR Chrysanthe Tan SUBMISSIONS COORDINATOR Adriana Widdoes ROVING GENIUSES AND EDITORS-AT-LARGE Anthony Miller • Dwayne Moser • David L. Ulin ART DIRECTOR Ophelia Chong COVER PHOTO Tom Martinelli AD DIRECTOR Patrick Benjamin GUIDING LIGHT AND VISIONARY Gail Swanlund FOUNDING FATHER Jon Wagner Black Clock © 2015 California Institute of the Arts Black Clock: ISBN: 978-0-9836625-8-7 Black Clock is published semi-annually under cover of night by the MFA Creative Writing Program at the California Institute of the Arts, 24700 McBean Parkway, Valencia CA 91355 THANK YOU TO THE ROSENTHAL FAMILY FOUNDATION FOR ITS GENEROUS SUPPORT Issues can be purchased at blackclock.org Editorial email: [email protected] Distributed through Ingram, Ingram International, Bertrams, Gardners and Trust Media. Printed by Lightning Source 3 Norman Dubie The Doorbell as Fiction Howard Hampton Field Trips to Mars (Psychedelic Flashbacks, With Scones and Jam) Jon Savage The Third Eye Jerry Burgan with Alan Rifkin Wounds to Bind Kyra Simone Photo Album Ann Powers The Sound of Free Love Claire -

NVS 1-1 A-Williamson

“The Dead Man Touch’d Me From the Past”: Reading as Mourning, Mourning as Reading in A. S. Byatt’s ‘The Conjugial Angel’ Andrew Williamson (The University of Queensland, Australia) Abstract: At the centre of nearly every A. S. Byatt novel is another text, often Victorian in origin, the presence of which stresses her demand for an engagement with, and a reconsideration of, past works within contemporary literature. In conversing with the dead in this way, Byatt, in her own, consciously experimental, work, illustrates what she has elsewhere called “the curiously symbiotic relationship between old realism and new experiment.” This symbiotic relationship demands further exploration within Possession (1990) and Angels and Insects (1992), as these works resurrect the Victorian period. This paper examines the recurring motif of the séance in each novel, a motif that, I argue, metaphorically correlates spiritualism and the acts of reading and writing. Byatt’s literary resurrection creates a space in which received ideas about Victorian literature can be reconsidered and rethought to give them a new critical life. In a wider sense, Byatt is examining precisely what it means for a writer and their work to exist in the shadow of the ‘afterlife’ of prior texts. Keywords: A. S. Byatt, ‘The Conjugial Angel’, mourning, neo-Victorian novel, Possession , reading, séance, spiritualism, symbiosis. ***** Nature herself occasionally quarters an inconvenient parasite on an animal towards whom she has otherwise no ill-will. What then? We admire her care for the parasite. (George Eliot 1979: 77) Towards the end of A. S. Byatt’s Possession (1990), a group of academics is gathered around an unread letter recently exhumed from the grave of a pre-eminent Victorian poet, the fictional Randolph Henry Ash. -

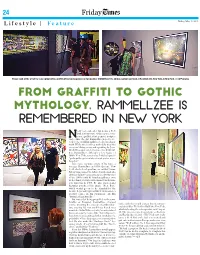

P24-25 Layout 1

24 Friday Lifestyle | Feature Friday, May 11, 2018 People look at the art of the conceptual artist, graffiti artist, hip-hop pioneer, Rammellzee (RAMMSLLZSS), during a private preview at Red Bull Arts New York, in New York. — AFP photos From graffiti to gothic mythology, Rammellzee is remembered in New York early a decade after his death, a New NYork retrospective of the rapper, com- poser, graffiti artist, painter, sculptor and cosmic theorist Rammellzee hopes to re- veal to the world his multifaceted, iconoclastic work. While street art has worked its way into everyone’s living room, and a painting by Jean- Michel Basquiat can fetch more that $100 mil- lion, Rammellzee, although a key figure of 1980s New York, remains-as Sotheby’s put it- ”perhaps the greatest street artist you’ve never heard of.” Like many aspiring artists of his time, a teenage Rammellzee in 1970s Queens, New York, started out spraying on subway trains. But as time passed, his letters transformed into abstract figures-compositions that by the start of the 1980s could be found in galleries, even Rotterdam’s prestigious Boijmans Van Beunin- gen museum in 1983. He also rapped-and Basquiat produced-his single “Beat Bop,” which would go on to be sampled by the Beastie Boys and Cypress Hill. Next, he made a stealthy cameo in Jim Jarmusch’s cult film “Stranger Than Paradise.” But instead of being propelled to the same heights as Basquiat, Rammellzee changed course-inventing the concept of gothic futur- rative arch that could convey his intentions,” ism, creating his own mythology based on a explained Max Wolf of Red Bull Arts New York, manifesto. -

October 29, 2013 (XXVII:10) Jim Jarmusch, DEAD MAN (1995, 121 Min)

October 29, 2013 (XXVII:10) Jim Jarmusch, DEAD MAN (1995, 121 min) Directed by Jim Jarmusch Original Music by Neil Young Cinematography by Robby Müller Johnny Depp...William Blake Gary Farmer...Nobody Crispin Glover...Train Fireman John Hurt...John Scholfield Robert Mitchum...John Dickinson Iggy Pop...Salvatore 'Sally' Jenko Gabriel Byrne...Charlie Dickinson Billy Bob Thornton...Big George Drakoulious Alfred Molina...Trading Post Missionary JIM JARMUSCH (Director) (b. James R. Jarmusch, January 22, 1981 Silence of the North, 1978 The Last Waltz, 1978 Coming 1953 in Akron, Ohio) directed 19 films, including 2013 Only Home, 1975 Shampoo, 1972 Memoirs of a Madam, 1970 The Lovers Left Alive, 2009 The Limits of Control, 2005 Broken Strawberry Statement, and 1967 Go!!! (TV Movie). He has also Flowers, 2003 Coffee and Cigarettes, 1999 Ghost Dog: The Way composed original music for 9 films and television shows: 2012 of the Samurai, 1997 Year of the Horse, 1995 Dead Man, 1991 “Interview” (TV Movie), 2011 Neil Young Journeys, 2008 Night on Earth, 1989 Mystery Train, 1986 Down by Law, 1984 CSNY/Déjà Vu, 2006 Neil Young: Heart of Gold, 2003 Stranger Than Paradise, and 1980 Permanent Vacation. He Greendale, 2003 Live at Vicar St., 1997 Year of the Horse, 1995 wrote the screenplays for all his feature films and also had acting Dead Man, and 1980 Where the Buffalo Roam. In addition to his roles in 10 films: 1996 Sling Blade, 1995 Blue in the Face, 1994 musical contributions, Young produced 7 films (some as Bernard Iron Horsemen, 1992 In the Soup, 1990 The Golden Boat, 1989 Shakey): 2011 Neil Young Journeys, 2006 Neil Young: Heart of Leningrad Cowboys Go America, 1988 Candy Mountain, 1987 Gold, 2003 Greendale, 2003 Live at Vicar St., 2000 Neil Young: Helsinki-Naples All Night Long, 1986 Straight to Hell, and 1984 Silver and Gold, 1997 Year of the Horse, and 1984 Solo Trans. -

Dead Man the Ultimate Viewing of William Blake

1 December 20, 2007 Terri C. Smith John Pruitt: Narrative film 311 Tangled jungles, blind paths, secret passage, lost cities invade our perception. The sites in films are not to be located or trusted. All is out of proportion. Scale inflates or deflates into uneasy dimensions. We wander between the towering and the bottomless. We are lost between the abyss within us and the boundless horizons outside us. Any film wraps us in uncertainty. The longer we look through a camera or watch a projected image the remoter the world becomes, yet we begin to understand that remoteness more. -- Robert Smithson from Cinematic Atopia1 Dead Man The Ultimate Viewing of William Blake When Jim Jarmusch incorporated his improvisational directorial approach, lean script- writing, minimalist aesthetic and passive characters into the seeming transcendental Western, Dead Man (1996), he subverted expectations of both his fans and detractors. The movie was polarizing for critics. During the time of its immediate reception, critics largely, seemed to either love it or hate it. Many people, especially non-European critics, saw Dead Man as explicitly ideological and full of itself. It was described as “a 1 Robert Smithson, “Cinematic Atopia” in Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, ed. Jack Flam, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), p. 141 1 2 misguided – albeit earnest undergraduate undertaking,”2 a “sadistic”3 127 minutes, “coy to a fault,”4 “punishingly slow,”5 and “shallow and trite.”6 Jarmusch is also attacked for being “hipper-than-thou”7 and smug. The juxtaposition of styles and genres bothered some. An otherwise positive review critiqued the “not-always-successful juxtapositions of humor and gore.” 8 For many it was Dead Man as a revisionist Western that became a problem. -

1 Ma, Mu and the Interstice: Meditative Form in the Cinema of Jim

1 Ma, Mu and the Interstice: Meditative Form in the Cinema of Jim Jarmusch Roy Daly, Independent Scholar Abstract: This article focuses on the centrality of the interstice to the underlying form of three of Jim Jarmusch’s films, namely, Stranger Than Paradise (1984), Dead Man (1995) and The Limits of Control (2009). It posits that the specificity of this form can be better understood by underlining its relation to aspects of Far Eastern form. The analysis focuses on the aforementioned films as they represent the most fully-fledged examples of this overriding aesthetic and its focus on interstitial space. The article asserts that a consistent aesthetic sensibility pervades the work of Jarmusch and that, by exploring the significance of the Japanese concepts of mu and ma, the atmospheric and formal qualities of this filmmaker’s work can be elucidated. Particular emphasis is paid to the specific articulation of time and space and it is argued that the films achieve a meditative form due to the manner in which they foreground the interstice, transience, temporality and subjectivity. The cinema of Jim Jarmusch is distinctive for its focus on the banal and commonplace, as well as its rejection of narrative causality and dramatic arcs in favour of stories that are slight and elliptical. Night on Earth (1991), a collection of five vignettes that occur simultaneously in separate taxis in five different cities, explores the interaction between people within the confined space of a taxi cab and the narrow time-frame necessitated by such an encounter, while Coffee and Cigarettes (2004) focuses on similarly themed conversations that take place mostly in small cafes.1 The idea of restricting a film to such simple undertakings is indicative of Jarmusch’s commitment to exploring underdeveloped moments of narrative representation. -

Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, No

ISSN: 2471-6839 Cite this article: Peter R. Kalb, review of Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 1 (Spring 2021), doi.org/10.24926/24716839.11870. Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation Curated by: Liz Munsell, The Lorraine and Alan Bressler Curator of Contemporary Art, and Greg Tate Exhibition schedule: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, October 18, 2020–July 25, 2021 Exhibition catalogue: Liz Munsell and Greg Tate, eds., Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation, exh. cat. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2020. 199 pp.; 134 color illus. Cloth: $50.00 (ISBN: 9780878468713) Reviewed by: Peter R. Kalb, Cynthia L. and Theodore S. Berenson Chair of Contemporary Art, Department of Fine Arts, Brandeis University It may be argued that no artist has carried more weight for the art world’s reckoning with racial politics than Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960–1988). In the 1980s and 1990s, his work was enlisted to reflect on the Black experience and art history; in the 2000 and 2010s his work diversified, often single-handedly, galleries, museums, and art history surveys. Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation attempts to share in these tasks. Basquiat’s artwork first appeared in lower Manhattan in exhibitions that poet and critic Rene Ricard explained, “made us accustomed to looking at art in a group, so much so that an exhibit of an individual’s work seems almost antisocial.”1 The earliest efforts to historicize the East Village art world shared this spirit of sociability.