Year of Revolutions: 1848 in 1848, the Tensions That Had Been Present In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enjoy Your Visit!!!

declared war on Austria, in alliance with the Papal States and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, and attacked the weakened Austria in her Italian possessions. embarked to Sicily to conquer the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, ruled by the But Piedmontese Army was defeated by Radetzky; Charles Albert abdicated Bourbons. Garibaldi gathered 1.089 volunteers: they were poorly armed in favor of his son Victor Emmanuel, who signed the peace treaty on 6th with dated muskets and were dressed in a minimalist uniform consisting of August 1849. Austria reoccupied Northern Italy. Sardinia wasn’t able to beat red shirts and grey trousers. On 5th May they seized two steamships, which Austria alone, so it had to look for an alliance with European powers. they renamed Il Piemonte and Il Lombardo, at Quarto, near Genoa. On 11th May they landed at Marsala, on the westernmost point of Sicily; on 15th they Room 8 defeated Neapolitan troops at Calatafimi, than they conquered Palermo on PALAZZO MORIGGIA the 29th , after three days of violent clashes. Following the victory at Milazzo (29th May) they were able to control all the island. The last battle took MUSEO DEL RISORGIMENTO THE DECADE OF PREPARATION 1849-1859 place on 1st October at Volturno, where twenty-one thousand Garibaldini The Decade of Preparation 1849-1859 (Decennio defeated thirty thousand Bourbons soldiers. The feat was a success: Naples di Preparazione) took place during the last years of and Sicily were annexed to the Kingdom of Sardinia by a plebiscite. MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY HISTORY LABORATORY Risorgimento, ended in 1861 with the proclamation CIVIC HISTORICAL COLLECTION of the Kingdom of Italy, guided by Vittorio Emanuele Room 13-14 II. -

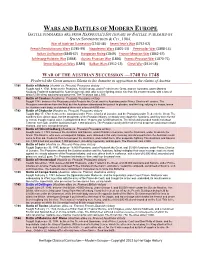

Wars and Battles of Modern Europe Battle Summaries Are from Harbottle's Dictionary of Battles, Published by Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1904

WARS AND BATTLES OF MODERN EUROPE BATTLE SUMMARIES ARE FROM HARBOTTLE'S DICTIONARY OF BATTLES, PUBLISHED BY SWAN SONNENSCHEIN & CO., 1904. War of Austrian Succession (1740-48) Seven Year's War (1752-62) French Revolutionary Wars (1785-99) Napoleonic Wars (1801-15) Peninsular War (1808-14) Italian Unification (1848-67) Hungarian Rising (1849) Franco-Mexican War (1862-67) Schleswig-Holstein War (1864) Austro Prussian War (1866) Franco Prussian War (1870-71) Servo-Bulgarian Wars (1885) Balkan Wars (1912-13) Great War (1914-18) WAR OF THE AUSTRIAN SUCCESSION —1740 TO 1748 Frederick the Great annexes Silesia to his domains in opposition to the claims of Austria 1741 Battle of Molwitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought April 8, 1741, between the Prussians, 30,000 strong, under Frederick the Great, and the Austrians, under Marshal Neuperg. Frederick surprised the Austrian general, and, after severe fighting, drove him from his entrenchments, with a loss of about 5,000 killed, wounded and prisoners. The Prussians lost 2,500. 1742 Battle of Czaslau (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought 1742, between the Prussians under Frederic the Great, and the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine. The Prussians were driven from the field, but the Austrians abandoned the pursuit to plunder, and the king, rallying his troops, broke the Austrian main body, and defeated them with a loss of 4,000 men. 1742 Battle of Chotusitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought May 17, 1742, between the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine, and the Prussians under Frederick the Great. The numbers were about equal, but the steadiness of the Prussian infantry eventually wore down the Austrians, and they were forced to retreat, though in good order, leaving behind them 18 guns and 12,000 prisoners. -

Battle of Custoza Newspaper

THE AUSTRIAN DAILY! PAGE1 JULY 26 1848 Batle of Custza Comes t an End. Te batle between te Austian Empire and te Kingdom of Sardinia has reached its brutal end. BACKGROUND: THE CONFLICT ENDS: te nortern Italian region. Te Tis fierce confontaton startd in Earlier tis mont, King Charles defeat of King Charles Albert comes January tis year, when in March Albert led his army across te t no surprise, and he now has been te cit of Milan revoltd against Mincio River, Italy, t engage wit forced by General Radetsky t sign Austian occupaton in what is now General Radetsky’s army. His a peace teat wit Austia. known as te “five days of Milan”. flawed plan, as revealed t te However, even tough tis was a King Charles Albert was in favor of public soon aftrwards, was t spectacular victry for Austia, bot te Milanese revolt, and declared occupy te hiltp and statgic twn sides had major casualtes. More war on Austia. General Radetsky of Custza, for military purposes. tan half of each side’s army was witdrew his toops fom Milan, and Aftr a vicious two-day batle lost, and many are now grieving for focused on seting up stong bases in between te Kingdom of Sardinia te dead. Verona, Mantua, Peschiera, and and te Austian Empire at tis Legnano. Charles Albert ten locaton, General Radetsky has THE QUESTION: strmed Peschiera, and tok it over. emerged victrious, and has taken A queston now remains; wil peace Tis gave him hope tat would soon over Custza terefore driving out be upheld? Or wil tis be yet be lost. -

Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11Th Edition, Volume 5, Slice 5 - "Cat" to "Celt"

Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, Volume 5, Slice 5 - "Cat" to "Celt" By Various English A Doctrine Publishing Corporation Digital Book This book is indexed by ISYS Web Indexing system to allow the reader find any word or number within the document. Transcriber's notes: (1) Numbers following letters (without space) like C2 were originally (2) Characters following a carat (^) were printed in superscript. (3) Side-notes were relocated to function as titles of their respective (4) Macrons and breves above letters and dots below letters were not (5) [oo] stands for the infinity symbol. (6) The following typographical errors have been corrected: Article CATALONIA: "There is much woodland, but meadows and pastures are rare." 'There' amended from 'These'. Article CATALYSIS: "It seems in this, as in other cases, that additional compounds are first formed which subsequently react with the re-formation of the catalyst." 'additional' amended from 'addition'. Article CAVALRY: "... and as this particular branch of the army was almost exclusively commanded by the aristocracy it suffered most in the early days of the Revolution." 'army' amended from 'arm'. Article CECILIA, SAINT: "It was long supposed that she was a noble lady of Rome 594 who, with her husband and other friends whom she had converted, suffered martyrdom, c. 230, under the emperor Alexander Severus." 'martyrdom' amended from 'martydom'. Article CELT: "Two poets of this period, whom an English writer describes as 'the two filthy Welshmen who first smoked publicly in the streets,' -

LE MIE MEMORIE ARTISTICHE Giovanni Pacini

LE MIE MEMORIE ARTISTICHE Giovanni Pacini English translation: Adriaan van der Tang, October 2011 1 2 GIOVANNI PACINI: LE MIE MEMORIE ARTISTICHE PREFACE Pacini’s autobiography Le mie memorie artistiche has been published in several editions. For the present translation the original text has been used, consisting of 148 pages and published in 1865 by G.G. Guidi. In 1872 E. Sinimberghi in Rome published Le mie memorie artistiche di Giovanni Pacini, continuate dall’avvocato Filippo Cicconetti. The edition usually referred to was published in 1875 by Le Monnier in Florence under the title Le mie memorie artistiche: edite ed inedite, edited by Ferdinando Magnani. The first 127 pages contain the complete text of the original edition of 1865 – albeit with a different page numbering – extended with the section ‘inedite’ of 96 pages, containing notes Pacini made after publication of the 1865-edition, beginning with three ‘omissioni’. This 1875- edition covers the years as from 1864 and describes Pacini’s involvement with performances of some of his operas in several minor Italian theatres. His intensive supervision at the first performances in 1867 of Don Diego di Mendoza and Berta di Varnol was described as well, as were the executions of several of his cantatas, among which the cantata Pacini wrote for the unveiling of the Rossini- monument in Pesaro, his oratorios, masses and instrumental works. Furthermore he wrote about the countless initiatives he developed, such as the repatriation of Bellini’s remains to Catania and the erection of a monument in Arezzo in honour of the great poet Guido Monaco, much adored by him. -

ICRP Calendar

The notions of International Relations (IR) in capital letters and international relations (ir) in lowercase letters have two different meanings. The first refers to a scholarly discipline while the second one means a set of contemporary events with historical importance, which influences global-politics. In order to make observations, formulate theories and describe patterns within the framework of ‘IR’, one needs to fully comprehend specific events related to ‘ir’. It is why the Institute for Cultural Relations Policy (ICRP) believes that a timeline on which all the significant events of international relations are identified might be beneficial for students, scholars or professors who deal with International Relations. In the following document all the momentous wars, treaties, pacts and other happenings are enlisted with a monthly division, which had considerable impact on world-politics. January 1800 | Nationalisation of the Dutch East Indies The Dutch East Indies was a Dutch colony that became modern Indonesia following World War II. It was formed 01 from the nationalised colonies of the Dutch East India Company, which came under the administration of the Dutch government in 1800. 1801 | Establishment of the United Kingdom On 1 January 1801, the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland united to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Most of Ireland left the union as the Irish Free State in 1922, leading to the remaining state being renamed as the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland in 1927. 1804 | Haiti independence declared The independence of Haiti was recognized by France on 17 April 1825. -

1848, the European People's Spring

1848, the European People’s Spring 1848, the European People’s Spring Éric ANCEAU ABSTRACT In 1848, a revolutionary wave shook the conservative order that had presided over the fate of Europe since the fall of Napoleon and the Congress of Vienna in 1815. Rebellions drove out sovereigns or forced them to grant a constitution, and established new regimes founded on national sovereignty and fundamental rights. This was the “People’s Spring.” The European dimension of the event is undeniable, although its form and content remain open to debate. Map of the People’s Spring by Bertrand Jolivet Carlo Canella, Battle over Porta Tosa Gate in Milan, March 22, 1848, 1848, oil on canvas, 98 x 75 cm, Museum of the Risorgimento, Milan (Italy). The Porta Tosa (which became the Porta Vittoria in 1861) was one of Milan’s four major gates. On March 22, 1848, during the Five Days of Milan rebellion, it was the first gate to be conquered by the rebels thanks to the use of movable barricades. Lithograph by Frédéric Sorrieu, Universal Democratic and Social Republic: The Pact, subtitled “People, form a Holy Alliance and hold our hand,” 1848, Musée Carnavalet, Paris. A transnational European movement and its limits “Do you not feel, through a kind of instinctive intuition that cannot be analyzed but that is certain, that the ground is shaking once again in Europe? Do you not feel—how shall I call it?—that a revolutionary wind is blowing?” These prophetic lines from Alexis de Tocqueville’s Souvenirs, written in January 1848, show that the political crises affecting a number of countries took on a continental turn from the outset. -

Ph.D. Dissertation

Women in Arms: Gender in the Risorgimento, 1848–1861 By Benedetta Gennaro B. A., Università degli Studi di Roma “La Sapienza”, 1999 M. A., Miami University, 2002 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Italian Studies at Brown University Providence, Rhode Island May 2010 c Copyright 2010 by Benedetta Gennaro This dissertation by Benedetta Gennaro is accepted in its present form by the Department of Italian Studies as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Suzanne Stewart-Steinberg, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date Caroline Castiglione, Reader Date Massimo Riva, Reader Date David Kertzer, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date Sheila Bonde, Dean of the Graduate School iii VITA Benedetta Gennaro was born in Rome on January 18th, 1975. She grew up in Rome and studied at the University of Rome, “La Sapienza” where she majored in Mass Communication. She wrote her undergraduate thesis on the history of the American Public Broadcasting System (1999), after spending a long and snowy winter in the middle of the Nebraskan plains, interning at NET the Nebraska Educational Televi- sion Network. She went on to receive her M.A. in Mass Communication from Miami University (Oxford, Ohio) in 2002. Her master’s thesis focused on an analysis of gender, race, and class in prime-time television opening credits. She decided to move west, to Portland, Oregon, where she worked for three years for the Northwest Film Center, a branch of the Portland Art Museum, organizing the yearly Portland Inter- national Film Festival. -

The Thun-Hohenstein University Reforms 1849–1860

The Thun-Hohenstein University Reforms 1849–1860 Conception – Implementation – Aftermath Edited by Christof Aichner and Brigitte Mazohl VERÖFFENTLICHUNGEN DER KOMMISSION FÜR NEUERE GESCHICHTE ÖSTERREICHS Band 115 Kommission für Neuere Geschichte Österreichs Vorsitzende: em. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Brigitte Mazohl Stellvertretender Vorsitzender: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Reinhard Stauber Mitglieder: Dr. Franz Adlgasser Univ.-Prof. Dr. Peter Becker Univ.-Prof. i. R. Dr. Ernst Bruckmüller Univ.-Prof. Dr. Laurence Cole Univ.-Prof. Dr. Margret Friedrich Univ.-Prof. Dr. Elisabeth Garms-Cornides Univ.-Prof. Dr. Michael Gehler Univ.-Doz. Mag. Dr. Andreas Gottsmann Univ.-Prof. Dr. Margarete Grandner em. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Hanns Haas Univ.-Prof. i. R. Dr. Wolfgang Häusler Univ.-Prof. i. R. Dr. Ernst Hanisch Univ.-Prof. Dr. Gabriele Haug-Moritz Dr. Michael Hochedlinger Univ.-Prof. Dr. Lothar Höbelt Mag. Thomas Just Univ.-Prof. i. R. Dr. Grete Klingenstein em. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Alfred Kohler Univ.-Prof. Dr. Christopher Laferl Gen. Dir. Univ.-Doz. Dr. Wolfgang Maderthaner Dr. Stefan Malfèr Gen. Dir. i. R. H.-Prof. Dr. Lorenz Mikoletzky Dr. Gernot Obersteiner Dr. Hans Petschar em. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Helmut Rumpler Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Martin Scheutz em. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Gerald Stourzh Univ.-Prof. Dr. Arno Strohmeyer Univ.-Prof. i. R. Dr. Arnold Suppan Univ.-Doz. Dr. Werner Telesko Univ.-Prof. Dr. Thomas Winkelbauer Sekretär: Dr. Christof Aichner The Thun-Hohenstein University Reforms 1849–1860 Conception – Implementation – Aftermath Edited by Christof Aichner and Brigitte Mazohl Published with the support from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF): PUB 397-G28 Open access: Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported License. -

Was Opera in Italy the Nineteenth Century's Pop Music?

Was Opera in Italy the Nineteenth Century’s Pop Music? Diverse Aspects of Opera in Milan before Italian Unifi cation Raff aella Bianchi (Loughborough/UK) »William Shakespeare is now seen as the epitome of high culture, yet to his contemporaries his work would have been understood as popular theatre.« (Storey 1993:8) 1. What is it Popular Culture? With its aristocratic origins, the conspicuous budget required for its performance, and its appeal to a classically educated audience, opera today is commonly associ- ated with high culture. This article addresses the question whether opera in nine- teenth-century Italy can be considered as popular music. My work a empts to en- gage the concept of the »popular« by applying diverse aspects of this concept to the discourse of performing opera in nineteenth-century Milan prior to Italian unifi ca- tion. The concept of popular music is a relatively new one. Is it possible to apply it to the musical culture of the nineteenth century? To ask this question might be useful for an understanding of the focus of my analysis, namely the concept of popular culture, and also for the object of my scrutiny, the genre of opera in Milan. This article suggests that from a cultural-studies perspective, opera can be considered as popu- lar music. To defi ne popular music, however, is not a straightforward task. As Storey1 shows, popular culture is defi ned in diff erent ways by cultural theorists. I will refer to certain works that describe opera as popular culture, and consider their specifi c concepts of popular culture. -

Evaristo De Chirico

111 EVARISTO DE CHIRICO Paolo Picozza I. My father was a man of the nineteenth century; he was an engineer and also a gentleman of olden times, courageous, loyal, hard-working, intelligent and good. He had studied in Florence and Turin, and he was the only one of a large family of gentry who had wanted to work. Like many men of the nineteenth century he had various capacities and virtues: he was a very good engineer, had very fine handwriting, he drew, had a good ear for music, had gifts of observation and irony, hated injustice, loved animals, treated the rich and powerful in a lofty manner, and was always ready to protect and help the weak and the poor. This means that my father, like many men of that time, was the exact opposite of most men of today, who lack a sense of direction and any character, are unskilled, incapable and, on top of everything, are unchivalrous, highly opportunist and full of stupidity.1 Like all true gentlemen of the nineteenth century my father was pro-Jewish.2 In passing by the monument commemorating King Umberto’s tragic death, far away memories from my childhood surfaced from the most remote recesses of my memory. I remembered my father, in Greece, when I was still a child. On the walls of the railway engineer office, among photographs of loco- motives and railway bridges, hung two large portraits of King Umberto and Queen Margherita in carved wooden black frames. My father came home one evening with a newspaper displaying the announce- ment of the king’s assassination in large letters. -

History Education and the School Textbook in Fascist Italy: Fascist National Identity and Historiography in the Libro Unico Di Stato

Royal Holloway School of Modern Languages, Literatures and Cultures Italian History Education and the School textbook in Fascist Italy: Fascist National Identity and Historiography in the Libro unico di Stato by Jun Young Moon Supervisor Dr. Fabrizio De Donno Advisor Dr. Giuliana Pieri A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Royal Holloway College, University of London 2015 DECLARATION OF AUTHORSHIP I, , hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: ABSTRACT The Fascist government in Italy monopolised the textbook for primary schools in 1930. This act was the regime’s bid to cultivate the Italiano nuovo and to transform Italy into a Fascist nation. By differentiating its education from the conventional contents and practices in Liberal Italy, the Fascist regime aimed at imbuing Italian children with a new national identity, which was expected to be a cornerstone of the Fascist Empire. History was regarded as one of the most crucial subjects for this goal and was high on the list of the regime’s priorities when the state school textbook, the Libro unico di Stato, was written. This research is a study of the historiography in the Fascist state textbook. Despite the importance of history education and the school textbook in the project to Fascistise Italy, few studies are entirely devoted to analysing Mussolini regime’s view of history in the Libro unico di Stato. This thesis attempts to redress this gap. By analysing the Libro unico’s historical narrative –its messages, tropes, symbolism, thematic concerns, narrative strategies, languages, and periodization in all 9 volumes-, this thesis demonstrates what ideological messages and values were taught by Fascist schools via history textbooks, how the textbook narrative transmitted Fascism’s world view and its historical interpretation to pupils, and what the characteristic of the Fascist historiography in education was.