Jessie White Mario (1832-1906), C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artistic Identity in the Published Writings of Margaret Thomas (C1840-1929)

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 1954-2016 University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1993 Artistic identity in the published writings of Margaret Thomas (c1840-1929) Lynn Patricia Brunet University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Brunet, Lynn Patricia, Artistic identity in the published writings of Margaret Thomas (c1840-1929), Master of Creative Arts (Hons.) thesis, School of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1993. -

Gen. Luigi Mondini, / Per Modesto Ma Vivissimo Omaggio, / L'a

ALESSANDRO ALLEMANO IL FONDO BIBLIOGRAFICO “GENERALE LUIGI MONDINI” DEL COMUNE DI GRAZZANO BADOGLIO CATALOGO DELLE SEZIONI RISORGIMENTO - STORIA SICILIANA RIVISTE Comune di Grazzano Badoglio 2011 2 PREMESSA Esce, in occasione delle celebrazioni del 150° anniversario dell’Unità d’Italia, la prima parte del catalogo del fondo bibliografico del Generale di Corpo d’armata Luigi Mondini, donato al Comune di Grazzano Badoglio nel 1988. Tenuto conto della personalità dell’alto Ufficiale e degli incarichi da Lui disimpegnati nel corso di una lunga carriera, oltre che in segno di rispetto alla Sua memoria e alla gentilezza dimostrata dai Suoi congiunti, la catalogazione di questa raccolta era doverosa, oltre che intellettualmente stimolante. La struttura di questo lavoro si discosta alquanto dai comuni cataloghi bibliografici compilati secondo le normative correnti: è più un inventario d’archivio che un’arida collezione di schede catalografiche. In particolare ho ritenuto importante segnalare le dediche autografe, le annotazioni personali e i numerosi inserti di lettere, ritagli di giornali, frammenti di appunti presenti in parecchi dei libri del fondo. In tal modo è stato possibile ricostruire le modalità di formazione di questa biblioteca, comprendere gli interessi del Generale e delineare una vasta rete di amicizie con un gran numero di studiosi, caratterizzate tutte dal comune amore per la Storia. Un ricco indice permette l’agevole reperimento delle schede in riferimento sia al soggetto che ai nomi di persona. La realizzazione di questo primo catalogo, cui seguiranno nel tempo anche quelli relativi alle altre sezioni, è stata possibile in primo luogo grazie all’entusiasmo e all’intraprendenza di Rosaria Lunghi, Sindaco di Grazzano Badoglio, che ha incentrato le locali manifestazioni di “Italia 150” proprio sulla conservazione e valorizzazione del fondo Mondini, promuovendo l’iniziativa dal titolo “Leggere il Risorgimento e la storia d’Italia”. -

Armiero, Marco. a Rugged Nation: Mountains and the Making of Modern Italy

The White Horse Press Full citation: Armiero, Marco. A Rugged Nation: Mountains and the Making of Modern Italy. Cambridge: The White Horse Press, 2011. http://www.environmentandsociety.org/node/3501. Rights: All rights reserved. © The White Horse Press 2011. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism or review, no part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, including photocopying or recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission from the publishers. For further information please see http://www.whpress.co.uk. A Rugged Nation Marco Armiero A Rugged Nation Mountains and the Making of Modern Italy: Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries The White Horse Press Copyright © Marco Armiero First published 2011 by The White Horse Press, 10 High Street, Knapwell, Cambridge, CB23 4NR, UK Set in 11 point Adobe Garamond Pro Printed by Lightning Source All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism or review, no part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, including photocopying or recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-874267-64-5 But memory is not only made by oaths, words and plaques; it is also made of gestures which we repeat every morning of the world. And the world we want needs to be saved, fed and kept alive every day. -

Il Monopolio Del Patriottismo. Lettere Sulla Questione

Antonio Panizzi Il monopolio del patriottismo Lettere sulla questione meridionale (1863) a cura di William Spaggiari PANIZZI-604-1-fronte.indd 1 11/06/13 15.29 I NTRODUZIONE 1. – Molto si era adoperato Antonio Panizzi per la causa italiana, con alterne fortune, sin dai tempi della giovanile attività cospirativa nel ducato di Modena e a Parma, dove aveva conseguito la laurea in legge. Sfuggito all’arresto a Brescello, il suo paese natale, ai margini del territorio esten- se, una volta giunto in Inghilterra svolse una intensa propaganda contro i sovrani restaurati, pubblicando lunghi articoli sui giornali più autorevoli. I primi due, nel 1824, per la «Edinburgh Review», si intitolavano signifi- cativamente Italy e Austria, e gli ultimi, nel 1851, sullo stesso periodico, Kings and popes e Neapolitan justice; nell’insieme, un centinaio di fitte pa- gine 1. Ma costanti, fino agli anni dell’unità nazionale, furono il suo lavoro diplomatico presso le autorità di governo a Londra (Cavour vedeva in lui una sorta di ambasciatore non ufficiale) e l’appoggio (anche nella forma di sovvenzioni economiche) fornito a chi di volta in volta, al di là degli schieramenti, si dimostrava pronto all’azione, contro le lungaggini e le ma- novre diplomatiche; come Agostino Bertani, col quale nel 1855 organizzò un tentativo di liberazione dei detenuti politici nelle carceri borboniche 2. Pur avendo dichiarato una volta di agire «come un Inglese che ap- partiene ad un certo partito – che ora è quello dell’opposizione» (cioè ai whigs, allora contrapposti al ministero tory di Robert Peel) 3, Panizzi fu sempre estraneo a gruppi e correnti; così, quelli che erano, il più delle volte, episodi riconducibili ad un vigoroso spirito di indipendenza, nella prospettiva della liberazione dai governi reazionari, vennero poi facilmen- te interpretati, per il loro segno politico non sempre omogeneo, come iniziative legate ad una considerazione superficiale degli eventi, e quindi persino controproducenti. -

Enjoy Your Visit!!!

declared war on Austria, in alliance with the Papal States and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, and attacked the weakened Austria in her Italian possessions. embarked to Sicily to conquer the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, ruled by the But Piedmontese Army was defeated by Radetzky; Charles Albert abdicated Bourbons. Garibaldi gathered 1.089 volunteers: they were poorly armed in favor of his son Victor Emmanuel, who signed the peace treaty on 6th with dated muskets and were dressed in a minimalist uniform consisting of August 1849. Austria reoccupied Northern Italy. Sardinia wasn’t able to beat red shirts and grey trousers. On 5th May they seized two steamships, which Austria alone, so it had to look for an alliance with European powers. they renamed Il Piemonte and Il Lombardo, at Quarto, near Genoa. On 11th May they landed at Marsala, on the westernmost point of Sicily; on 15th they Room 8 defeated Neapolitan troops at Calatafimi, than they conquered Palermo on PALAZZO MORIGGIA the 29th , after three days of violent clashes. Following the victory at Milazzo (29th May) they were able to control all the island. The last battle took MUSEO DEL RISORGIMENTO THE DECADE OF PREPARATION 1849-1859 place on 1st October at Volturno, where twenty-one thousand Garibaldini The Decade of Preparation 1849-1859 (Decennio defeated thirty thousand Bourbons soldiers. The feat was a success: Naples di Preparazione) took place during the last years of and Sicily were annexed to the Kingdom of Sardinia by a plebiscite. MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY HISTORY LABORATORY Risorgimento, ended in 1861 with the proclamation CIVIC HISTORICAL COLLECTION of the Kingdom of Italy, guided by Vittorio Emanuele Room 13-14 II. -

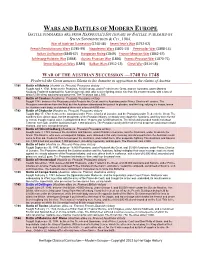

Wars and Battles of Modern Europe Battle Summaries Are from Harbottle's Dictionary of Battles, Published by Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1904

WARS AND BATTLES OF MODERN EUROPE BATTLE SUMMARIES ARE FROM HARBOTTLE'S DICTIONARY OF BATTLES, PUBLISHED BY SWAN SONNENSCHEIN & CO., 1904. War of Austrian Succession (1740-48) Seven Year's War (1752-62) French Revolutionary Wars (1785-99) Napoleonic Wars (1801-15) Peninsular War (1808-14) Italian Unification (1848-67) Hungarian Rising (1849) Franco-Mexican War (1862-67) Schleswig-Holstein War (1864) Austro Prussian War (1866) Franco Prussian War (1870-71) Servo-Bulgarian Wars (1885) Balkan Wars (1912-13) Great War (1914-18) WAR OF THE AUSTRIAN SUCCESSION —1740 TO 1748 Frederick the Great annexes Silesia to his domains in opposition to the claims of Austria 1741 Battle of Molwitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought April 8, 1741, between the Prussians, 30,000 strong, under Frederick the Great, and the Austrians, under Marshal Neuperg. Frederick surprised the Austrian general, and, after severe fighting, drove him from his entrenchments, with a loss of about 5,000 killed, wounded and prisoners. The Prussians lost 2,500. 1742 Battle of Czaslau (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought 1742, between the Prussians under Frederic the Great, and the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine. The Prussians were driven from the field, but the Austrians abandoned the pursuit to plunder, and the king, rallying his troops, broke the Austrian main body, and defeated them with a loss of 4,000 men. 1742 Battle of Chotusitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought May 17, 1742, between the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine, and the Prussians under Frederick the Great. The numbers were about equal, but the steadiness of the Prussian infantry eventually wore down the Austrians, and they were forced to retreat, though in good order, leaving behind them 18 guns and 12,000 prisoners. -

The Kingdom of Italy: Unity Or Disparity, 1860-1945

The Kingdom of Italy: Unity or Disparity, 1860-1945 Part IIIb: The First Years of the Kingdom Governments of the Historic Left 1876-1900 Decline of the Right/Rise of the Left • Biggest issue dividing them had been Rome—now resolved • Emerging issues • Taxation, especially the macinato • Neglect of social issues • Free trade policies that hurt the South disproportionately • Limited suffrage • Piedmontization • Treatment of Garibaldi volunteers • Use of police against demonstrations The North-South divide • emerging issues more important to South • Many of Left leaders from South Elections of 1874 • Slim majority for Right Fall of Minghetti, March 1876 Appointment of a Left Prime Minister and the elections of November 1876 Agostino Depretis Benedetto Cairoli Francesco Crispi Antonio Starabba, Marchese di Rudinì Giovanni Giolitti Genl. Luigi Pelloux Prime Minister Dates in office Party/Parliament Key actions or events Agostino Depretis 25 March 1876 Left Coppino Law Lombardy 25 December 1877 Sonnino and Iacini inquiry into the problems of the South Railway construction continues with state aid 26 December 1877 Left Anarchist insurrection in Matese 24 March 1878 Benedetto Cairoli 24 March 1878 Left Attempted anarchist assassination of king Lombary 19 December 1878 Depretis 19 December 1878 Left 14 July 1879 Cairoli 14 July 1879 Left Costa founds Revolutionary Socialist Party of Romagna 25 November 1879 25 November 1879 Left 29 May 1881 Depretis 29 May 1881 Left Widened suffrage; first socialist elected 25 May 1883 Italy joins Austria-Hungary and Germany to create Triplice Use of trasformismo 25 May 1883 Left 30 March 1884 Final abolition of grist tax macinato 30 March 1884 Left First colonial venture into Assab and Massawa on Red Sea coast 29 June 1885 29 June 1885 Left Battle of Dogali debacle 4 April 1887 4 April 1887 Left 29 July 1887 Died in office Francesco Crispi 29 July 1887 Left 10-year tariff war with France begun Sicily 6 February 1891 Zanardelli penal code enacted; local govt. -

Battle of Custoza Newspaper

THE AUSTRIAN DAILY! PAGE1 JULY 26 1848 Batle of Custza Comes t an End. Te batle between te Austian Empire and te Kingdom of Sardinia has reached its brutal end. BACKGROUND: THE CONFLICT ENDS: te nortern Italian region. Te Tis fierce confontaton startd in Earlier tis mont, King Charles defeat of King Charles Albert comes January tis year, when in March Albert led his army across te t no surprise, and he now has been te cit of Milan revoltd against Mincio River, Italy, t engage wit forced by General Radetsky t sign Austian occupaton in what is now General Radetsky’s army. His a peace teat wit Austia. known as te “five days of Milan”. flawed plan, as revealed t te However, even tough tis was a King Charles Albert was in favor of public soon aftrwards, was t spectacular victry for Austia, bot te Milanese revolt, and declared occupy te hiltp and statgic twn sides had major casualtes. More war on Austia. General Radetsky of Custza, for military purposes. tan half of each side’s army was witdrew his toops fom Milan, and Aftr a vicious two-day batle lost, and many are now grieving for focused on seting up stong bases in between te Kingdom of Sardinia te dead. Verona, Mantua, Peschiera, and and te Austian Empire at tis Legnano. Charles Albert ten locaton, General Radetsky has THE QUESTION: strmed Peschiera, and tok it over. emerged victrious, and has taken A queston now remains; wil peace Tis gave him hope tat would soon over Custza terefore driving out be upheld? Or wil tis be yet be lost. -

OPERATORE SOCIO SANITARIO (Approvazione D.D

RAGGRUPPAMENTO TEMPORANEPO DI SCOPO UNIONE EUROPEA CAPOFILA Avviso Pubblico n.1/FSE/2018 - PERCORSI FORMATIVI PER IL CONSEGUIMENTO DELLA QUALIFICA DI OPERATORE SOCIO SANITARIO (approvazione D.D. n. 1347 del 26/11/2018 - B.U.R. 107/2018) OPERATORE SOCIO SANITARIO n. 1500 TEST Formallimac OSS OPERATORE SOCIO SANITARIO – N° 1500 TEST PER SELEZIONI ******************************************************************************************************************************* INDICE DEI TEST ************************************************************************************************************************************ 1 A) TEST ATTITUDINALI, LOGICA E RAGIONAMENTO NUMERICO N°750/1500 (DA SORTEGGIARE N°30 SU 60) ERRORE. IL SEGNALIBRO NON È DEFINITO. 2 B) TEST CULTURA GENERALE N°575/1500 (DA SORTEGGIARE N°23 SU 60) ERRORE. IL SEGNALIBRO NON È DEFINITO. 2.1 STORIA ERRORE. IL SEGNALIBRO NON È DEFINITO. 2.2 GEOGRAFIA 89 2.3 LETTERATURA 95 2.4 LINGUA ITALIANA ERRORE. IL SEGNALIBRO NON È DEFINITO. 2.5 SCIENZE DELLA TERRA ERRORE. IL SEGNALIBRO NON È DEFINITO. 2.6 ARTE ERRORE. IL SEGNALIBRO NON È DEFINITO. 2.7 MUSICA, TEATRO, CINEMA, TV ERRORE. IL SEGNALIBRO NON È DEFINITO. 2.8 INFORMATICA ERRORE. IL SEGNALIBRO NON È DEFINITO. 2.9 INGLESE ERRORE. IL SEGNALIBRO NON È DEFINITO. 2.10 SPORT ERRORE. IL SEGNALIBRO NON È DEFINITO. 2.11 VARIE ERRORE. IL SEGNALIBRO NON È DEFINITO. 3 C) TEST CITTADINANZA EUROPEA E EDUCAZIONE CIVICA N° 175/1500 (DA SORTEGGIARE N°7 SU 60) ERRORE. IL SEGNALIBRO NON È DEFINITO. 4 DICHIARAZIONE ASSOCIAZIONI ENTI F.P. ERRORE. IL SEGNALIBRO NON È DEFINITO. AVVISO 1/FSE/2018 – OPERATORE SOCIO SANITARIO 1 OPERATORE SOCIO SANITARIO – N° 1500 TEST PER SELEZIONI 1 A) TEST ATTITUDINALI, LOGICA E RAGIONAMENTO NUMERICO N°750/1500 (da sorteggiare n°30 su 60) 1) Cento conigli mangiano, in cento giorni, un quintale di carote. -

Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11Th Edition, Volume 5, Slice 5 - "Cat" to "Celt"

Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, Volume 5, Slice 5 - "Cat" to "Celt" By Various English A Doctrine Publishing Corporation Digital Book This book is indexed by ISYS Web Indexing system to allow the reader find any word or number within the document. Transcriber's notes: (1) Numbers following letters (without space) like C2 were originally (2) Characters following a carat (^) were printed in superscript. (3) Side-notes were relocated to function as titles of their respective (4) Macrons and breves above letters and dots below letters were not (5) [oo] stands for the infinity symbol. (6) The following typographical errors have been corrected: Article CATALONIA: "There is much woodland, but meadows and pastures are rare." 'There' amended from 'These'. Article CATALYSIS: "It seems in this, as in other cases, that additional compounds are first formed which subsequently react with the re-formation of the catalyst." 'additional' amended from 'addition'. Article CAVALRY: "... and as this particular branch of the army was almost exclusively commanded by the aristocracy it suffered most in the early days of the Revolution." 'army' amended from 'arm'. Article CECILIA, SAINT: "It was long supposed that she was a noble lady of Rome 594 who, with her husband and other friends whom she had converted, suffered martyrdom, c. 230, under the emperor Alexander Severus." 'martyrdom' amended from 'martydom'. Article CELT: "Two poets of this period, whom an English writer describes as 'the two filthy Welshmen who first smoked publicly in the streets,' -

The Original Documents Are Located in Box 16, Folder “6/3/75 - Rome” of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 16, folder “6/3/75 - Rome” of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 16 of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library 792 F TO C TATE WA HOC 1233 1 °"'I:::: N ,, I 0 II N ' I . ... ROME 7 480 PA S Ml TE HOUSE l'O, MS • · !? ENFELD E. • lt6~2: AO • E ~4SSIFY 11111~ TA, : ~ IP CFO D, GERALD R~) SJ 1 C I P E 10 NTIA~ VISIT REF& BRU SE 4532 UI INAl.E PAL.ACE U I A PA' ACE, TME FFtCIA~ RESIDENCE OF THE PR!S%D~NT !TA y, T ND 0 1 TH HIGHEST OF THE SEVEN HtL.~S OF ~OME, A CTENT OMA TtM , TH TEMPLES OF QUIRl US AND TME s E E ~oc T 0 ON THIS SITE. I THE CE TER OF THE PR!SENT QU?RINA~ IAZZA OR QUARE A~E ROMAN STATUES OF C~STOR .... -

Scanned by Scan2net

Giovanni Borgognone Dino Carpanetto dalla metà del Seicento alla fine dell'Ottocento Edizioni Scolastiche Il\ Bruno Mondadori ""' INDICE GENERALE NELVEUROPA DIANTICOREGIME ~~~ I ;J """~ -J..~ "~"' CAPITOLO 1 ANTICO REGIME E ASSOLUTISMO IN EUROPA 4 1 La società divisa per ceti 6 PER CAPIRE E RICORDARE La paulette 8 PER CAPIRE ERICORDARE Stati generali, Cortes, Diete, Parlamento 11 >VIDEOLEZIONE t:assolutismo in Europa 2 La monarchia assoluta 12 >VIDEO San Pietroburgo, la PER APPROFONDIRE I parlamenti in Francia 13 città di Pietro• Film: La presa del potere da parte di Luigi XIV 3 L'assolutismo di Luigi XIV 14 >GALLERIE DI IMMAGINI Il ritratto del sovrano assoluto• PERSONAGGIO Jean-Baptiste Colbert 16 La manifattura dei Gobelins ANALIZZARE LA FONTE Gli ugonotti in Francia: due editti a confronto 21 •La costruzione di Versailles• PER APPROFONDIRE Il mecenatismo di Luigi XIV 23 Pietro il Grande >PDF Gli approfondimenti del la STORIA ne/i'ARTE Il re governa da solo: capitolo• Repertorio di fonti la costruzione dell'immagine politica 24 aggiuntive• Repertorio di brani PER CAPIRE ERICORDARE La pace dei Pirenei 26 storiografici >VERIFICA INTERATTIVA 4 L'assolutismo nel resto d'Europa 28 DI CAPITOLO PERSONAGGIO Pietro il Grande 29 >AUDIOSINTESI PER CAPIRE ERICORDARE Gli Asburgo 34 >MAPPA INTERATTIVA la SINTESI del CAPITOLO 36 la MAPPA del CAPITOLO 37 gli EVENTI del CAPITOLO 37 . Dossier fonti FONTE 1 La testimonianza di un avversario dell'assolutismo: il duca di Saint-Simon 38 FONTE 2 !:economia francese ai tempi di Luigi XIV 39 FONTE 3 "Non inferiore