Good Politics” Property, Intersectionality, and the Making of the Anarchist Self

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction Relocating Within the Fisheries

TOPIC 4.5 Why would the population of the province fluctuate? What is the trend of population change in your community? What might be the impact of this trend? Introduction According to the 1901 Census, Newfoundland had lived in communities along the coast and made their a population of 220 984, including 3947 people living through the fishery – 70.6 per cent of the working recorded in Labrador. The population continued population. However, the fishing grounds of the east to increase through the first half of the twentieth coast had become overcrowded and families found it century, despite significant emigration to Canada and increasingly difficult to make a living in this industry. the United States. The geographical distribution of Consequently, people in some of the long-established people also began to change in response to push and fishing communities left their homes in search of less pull factors in the economy. Thousands of people populated bays where there would be less competition chose to leave their homes and relocate to regions that for fish. In each of the census years between 1891 and presented better economic opportunities. 1935, the population of the Harbour Grace, Carbonear, and Port de Grave districts consistently decreased* while the population of the St. George’s and St. Barbe Relocating Within districts on the west coast consistently increased. the Fisheries may be attributed to out-migration. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the vast *Some of this population decrease also majority of people in Newfoundland and Labrador still 4.74 Population dynamics by district, 1921-1935 % District 1921 1935 Change 4.73 Population dynamics by district, 1891-1921 Humber 4 745 15 166 220 % Grand Falls 9 227 14 373 56 District 1891 1901 1911 1921 Change White Bay 6 542 8 721 33 St. -

Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

individualist anarchism against bosses, inequality, corporate power, and structural poverty Edited by Gary Chartier & Charles W. Johnson Individualist anarchists believe in mutual exchange, not economic privilege. They believe in freed markets, not capitalism. They defend a distinctive response to the challenges of ending global capitalism and achieving social justice: eliminate the political privileges that prop up capitalists. Massive concentrations of wealth, rigid economic hierarchies, and unsustainable modes of production are not the results of the market form, but of markets deformed and rigged by a network of state-secured controls and privileges to the business class. Markets Not Capitalism explores the gap between radically freed markets and the capitalist-controlled markets that prevail today. It explains how liberating market exchange from state capitalist privilege can abolish structural poverty, help working people take control over the conditions of their labor, and redistribute wealth and social power. Featuring discussions of socialism, capitalism, markets, ownership, labor struggle, grassroots privatization, intellectual property, health care, racism, sexism, and environmental issues, this unique collection brings together classic essays by Cleyre, and such contemporary innovators as Kevin Carson and Roderick Long. It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism. “We on the left need a good shake to get us thinking, and these arguments for market anarchism do the job in lively and thoughtful fashion.” – Alexander Cockburn, editor and publisher, Counterpunch “Anarchy is not chaos; nor is it violence. This rich and provocative gathering of essays by anarchists past and present imagines society unburdened by state, markets un-warped by capitalism. -

Squatting – the Real Story

Squatters are usually portrayed as worthless scroungers hell-bent on disrupting society. Here at last is the inside story of the 250,000 people from all walks of life who have squatted in Britain over the past 12 years. The country is riddled with empty houses and there are thousands of homeless people. When squatters logically put the two together the result can be electrifying, amazing and occasionally disastrous. SQUATTING the real story is a unique and diverse account the real story of squatting. Written and produced by squatters, it covers all aspects of the subject: • The history of squatting • Famous squats • The politics of squatting • Squatting as a cultural challenge • The facts behind the myths • Squatting around the world and much, much more. Contains over 500 photographs plus illustrations, cartoons, poems, songs and 4 pages of posters and murals in colour. Squatting: a revolutionary force or just a bunch of hooligans doing their own thing? Read this book for the real story. Paperback £4.90 ISBN 0 9507259 1 9 Hardback £11.50 ISBN 0 9507259 0 0 i Electronic version (not revised or updated) of original 1980 edition in portable document format (pdf), 2005 Produced and distributed by Nick Wates Associates Community planning specialists 7 Tackleway Hastings TN34 3DE United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)1424 447888 Fax: +44 (0)1424 441514 Email: [email protected] Web: www.nickwates.co.uk Digital layout by Mae Wates and Graphic Ideas the real story First published in December 1980 written by Nick Anning by Bay Leaf Books, PO Box 107, London E14 7HW Celia Brown Set in Century by Pat Sampson Piers Corbyn Andrew Friend Cover photo by Union Place Collective Mark Gimson Printed by Blackrose Press, 30 Clerkenwell Close, London EC1R 0AT (tel: 01 251 3043) Andrew Ingham Pat Moan Cover & colour printing by Morning Litho Printers Ltd. -

Download As a PDF File

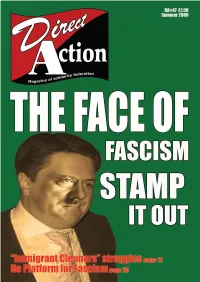

Direct Action www.direct-action.org.uk Summer 2009 Direct Action is published by the Aims of the Solidarity Federation Solidarity Federation, the British section of the International Workers he Solidarity Federation is an organi- isation in all spheres of life that conscious- Association (IWA). Tsation of workers which seeks to ly parallel those of the society we wish to destroy capitalism and the state. create; that is, organisation based on DA is edited & laid out by the DA Col- Capitalism because it exploits, oppresses mutual aid, voluntary cooperation, direct lective & printed by Clydeside Press and kills people, and wrecks the environ- democracy, and opposed to domination ([email protected]). ment for profit worldwide. The state and exploitation in all forms. We are com- Views stated in these pages are not because it can only maintain hierarchy and mitted to building a new society within necessarily those of the Direct privelege for the classes who control it and the shell of the old in both our workplaces Action Collective or the Solidarity their servants; it cannot be used to fight and the wider community. Unless we Federation. the oppression and exploitation that are organise in this way, politicians – some We do not publish contributors’ the consequences of hierarchy and source claiming to be revolutionary – will be able names. Please contact us if you want of privilege. In their place we want a socie- to exploit us for their own ends. to know more. ty based on workers’ self-management, The Solidarity Federation consists of locals solidarity, mutual aid and libertarian com- which support the formation of future rev- munism. -

New Anarchist Review Advertising in the Newanarchist Review June 1985, While on Their C/O 84B Whitechapel High Street Costs from £10 a Quarter Page

i 3 Balmoral Place Stirling, Scotland For trade distribution contact FK8 2RD 84b Whitechapel High Street London E1 7QX M A I L OR D E R Tel/fax 081 558 7732 DISTRIBUTION R iii-'\%1[_ X6%LE; 1/ ‘3 _|_i'| NI Iii O ‘Puxlci-IUi~lF G %*%ad,J\..1= BLACK _..ni|.miu¢ _ RED I BLQCK ... Rnmcho-lymhcufld *€' BREEN a BLMIK.....iiiuachv-Queen ,1-\ Plianchmle 5;7P%""¢5 L0 ..,....0u ab»! ’____ : <*REE"--I-=~‘~siw mi. Punchline *8: Let us Pray "'""~" 9"" Punchline *9: Time to remove GREEN 5 PURPLE.....Uc.ncn4 Jufflu N TFllAI\IGl_ESRq, ____, ,,,,,,,,,, Punchline ,10: Censorship oi bi"EEl'L ,,,l -znwiuli 8 $g?L":]":' """*'”"‘ L?;LB5"£5"";" Each copy £1 (post pai'd) in UK. M, ,,'f,‘;,'1;¢.5 are 11 30 Mm European orders £1.20 (post paid) mmoguijifgmflgrmfj, Mme European wholesale welcome Make cheques payable to ‘J Elliott’ only. Big Bang, Plain Wrapper comix, Punchline, Fixed Grin, Anti Shirts Catalogue from: BM ACTIVE LONDON WC1 N 3XX, LONDO 1M1Nflilllillilfilll __-rwuew ANARCH‘: ' ' '1... l'|1W ANARCHIST REVIEW NEW TITLES These titles are available from A Distribution (trade) counts what happened to No. 21 S September 1992 and AK Press (mail order) unless otherwise stated. several hundred travellers, See back page for addresses. who were attacked in a mili- Published by: Advertise taiy-style police operation in New Anarchist Review Advertising in the NewAnarchist Review June 1985, while on their c/o 84b Whitechapel High Street costs from £10 a quarter page. Series ANARCHY BY AN druggists’, or hard by a win- way to the Stonehenge festi- London E1 7QX discounts available. -

Revolution by the Book

AK PRESS PUBLISHING & DISTRIBUTION SUMMER 2009 AKFRIENDS PRESS OF SUMM AK PRESSER 2009 Friends of AK/Bookmobile .........1 Periodicals .................................51 Welcome to the About AK Press ...........................2 Poetry/Theater...........................39 Summer Catalog! Acerca de AK Press ...................4 Politics/Current Events ............40 Prisons/Policing ........................43 For our complete and up-to-date AK Press Publishing Race ............................................44 listing of thousands more books, New Titles .....................................6 Situationism/Surrealism ..........45 CDs, pamphlets, DVDs, t-shirts, Forthcoming ...............................12 Spanish .......................................46 and other items, please visit us Recent & Recommended .........14 Theory .........................................47 online: Selected Backlist ......................16 Vegan/Vegetarian .....................48 http://www.akpress.org AK Press Gear ...........................52 Zines ............................................50 AK Press AK Press Distribution Wearables AK Gear.......................................52 674-A 23rd St. New & Recommended Distro Gear .................................52 Oakland, CA 94612 Anarchism ..................................18 (510)208-1700 | [email protected] Biography/Autobiography .......20 Exclusive Publishers CDs ..............................................21 Arbeiter Ring Publishing ..........54 ON THE COVER : Children/Young Adult ................22 -

A Journal of Mutualist Anarchist Theory and History

LeftLiberty “It is the clash of ideas that casts the light!” The Gift Economy OF PROPERTY. __________ A Journal of Mutualist Anarchist Theory and History. NUMBER 2 August 2009 LeftLiberty It is the clash of ideas that casts the light! __________ “The Gift Economy of Property.” Issue Two.—August, 2009. __________ Contents: Alligations—A Tale of Three Approximations 2 New Proudhon Library Announcing Justice in the Revolution and in the Church—Part I 6 The Theory of Property, Chapter IX—Conclusion 8 Collective Reason “A Little Theory,” by Errico Malatesta 23 “The Mini-Manual of the Individualist Anarchist,” by Emile Armand 29 From the Libertarian Labyrinth 34 Socialism in the Plant World 35 “Mormon Co-operation,” by Dyer D. Lum 38 “Thomas Paine’s Anarchism,” by William Van Der Weyde 41 Mutualism: The Anarchism of Approximations Mutualism is APPROXIMATE 45 Mutualist Musings on Property 50 The Distributive Passions Another World is Possible, “At the Apex,” I 72 On alliance “Everyone here disagrees” 85 Editor: Shawn P. Wilbur A CORVUS EDITION LeftLiberty: the Gift Economy of Property: If several persons want to see the whole of a landscape, there is only one way, and that is, to turn their back to one another. If soldiers are sent out as scouts, and all turn the same way, observing only one point of the horizon, they will most likely return without having discovered anything. Truth is like light. It does not come to us from one point; it is reflected by all objects at the same time; it strikes us from every direction, and in a thousand ways. -

Anarchists in the Late 1990S, Was Varied, Imaginative and Often Very Angry

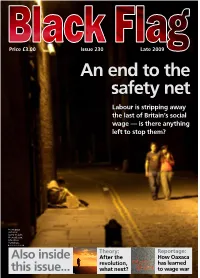

Price £3.00 Issue 230 Late 2009 An end to the safety net Labour is stripping away the last of Britain’s social wage — is there anything left to stop them? Front page pictures: Garry Knight, Photos8.com, Libertinus Yomango, Theory: Reportage: Also inside After the How Oaxaca revolution, has learned this issue... what next? to wage war Editorial Welcome to issue 230 of Black Flag, the fifth published by the current Editorial Collective. Since our re-launch in October 2007 feedback has generally tended to be positive. Black Flag continues to be published twice a year, and we are still aiming to become quarterly. However, this is easier said than done as we are a small group. So at this juncture, we make our usual appeal for articles, more bodies to get physically involved, and yes, financial donations would be more than welcome! This issue also coincides with the 25th anniversary of the Anarchist Bookfair – arguably the longest running and largest in the world? It is certainly the biggest date in the UK anarchist calendar. To celebrate the event we have included an article written by organisers past and present, which it is hoped will form the kernel of a general history of the event from its beginnings in the Autonomy Club. Well done and thank you to all those who have made this event possible over the years, we all have Walk this way: The Black Flag ladybird finds it can be hard going to balance trying many fond memories. to organise while keeping yourself safe – but it’s worth it. -

(Re)Membering the Quilombo: Race, Ethnicity, and the Politics of Recognition in Brazil

(Re)membering the Quilombo: Race, Ethnicity, and the Politics of Recognition in Brazil By: Elizabeth Farfán A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctorate of Philosophy with the University of California San Francisco in Medical Anthropology in the Graduate Division of the University of California Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Nancy Scheper-Hughes, Chair Professor Charles Briggs Professor Sharon Kaufman Professor Teresa Caldeira Fall 2011 Abstract by Elizabeth Farfán Joint Doctorate of Philosophy in Medical Anthropology with the University of California San Francisco University of California Berkeley Professor Nancy Scheper-Hughes, Chair African ancestry and collective resistance to slavery play a central role in access to constitutional rights for Brazilians living in rural black communities denominated comunidades remanescentes de quilombos. In the effort to repatriate lands to the descendants of quilombolas or fugitive slaves, the Brazilian government, together with the Brazilian Anthropological Association, and Black Movement activists, turned rural black communities into national patrimony through a series of public policies that emphasize their ethnic and cultural difference by connecting them to quilombo ancestors. Article 68 of the 1988 Brazilian constitution declared that any descendants of quilombos who were still occupying their ancestor’s lands should be recognized as owners and granted land titles by the federal government. With the help of NGOs, rural black communities are re-learning their identity and becoming quilombos in order to obtain the land and social rights they need to continue surviving. While the quilombo clause may seem like an important historical change in the ability of black Brazilians to use the constitution to their advantage, it is important to ask what the stakes are of becoming a quilombo for the residents of a community. -

Stumbo Visits Trigg County There Was Also One Fatality, Gray Said

rr ci Sons look Binding S o r i m p o r t , !4 i* k92hk ®he■ (EafcigDevoted toiRecori) the best interest of Cadiz ond Trigg County VOLUME 102 NUMBER 1 THURSDAY, JANUARY 6, 1983 ONE SECTION, 14 PAGES PRICE 20 CENTS f: V •> \ & M '* f l . \ ■ \ ft fit# \J % v \ H ' l r a Construction to start ■ x / V > W A j\; .-A \ 0/ \ ' A-. X.. < ;X.N:- w W V. # on industrial park road M v l i J David Shore, in a report to the Judge Zelner Cossey told the rv m11 court that a local historical society Trigg County Fiscal Court, said M r Tuesday that construction would is interested in saving the Muddy l?Pv Wl start on the access road into the Fork bridge on Adams Mill Road. \ * new industrial park as soon as The bridge was built in 1889. fe|. - \ ;v ; m y j / weather permits. Cossey said the bridge could not Shore said that he had received be saved under the present federal Vf :: the plans for the road from Howard bridge-building program but that a ■ ■ ® k r , \ K. Bell and bids were taken on the member of the historical transpor tation division of the state highway construction of the road among loc : . : , A m J al contractors. department is coming down to look The road will be built by Anthony at the bridge. :\\ V • -- AH w \. %• 4 " . Fourshee, a Trigg County contrac “We may be able to re-route the . ••• r*& , ......... U tor, for $5,000. His was the only bid road and build the new bridge far for the construction. -

Fall Sampler

Falling leaves. Uplifted hearts. Romance to move you. As the weather cools, get cozy with these heartwarming stories that are sure to inspire and delight you as much as your favorite fall colors. **Enjoy this FREE digital sampler featuring extended excerpts of new books by bestselling authors!** Featuring extended excerpts of: Texas Proud by Diana Palmer Claiming His Bollywood Cinderella by Tara Pammi Rookie Instincts by Carol Ericson Claiming the Rancher's Heir by Maisey Yates Chapter One Her name was Bernadette Epperson, but everybody she knew in Jacobsville, Texas, called her Bernie. She was Blake Kemp’s new paralegal, and she shared the office with Olivia Richards, who was also a paralegal. They had replaced former employees, one who’d mar- ried and moved away, the other who’d gone to work in San Antonio for the DA there. They were an interesting contrast: Olivia, the tall, willowy brunette, and Bernie, the slender blonde with long, thick platinum blond hair. They’d known each other since grammar school and they were friends. It made for a relaxed, happy office atmosphere. Ordinarily, one paralegal would have been adequate for the Jacobs County district attorney’s office. But the DA, Blake Kemp, had hired Olivia to also work as a Texas Prou_9781335894823_txt_304135.indd 7 8/19/20 11:22 AM 8 TEXAS PROUD part-time paralegal. That was because Olivia covered for her friend at the office when Bernie had flares of rheu- matoid arthritis. It was one of the more painful forms of arthritis, and when she had attacks it meant walk- ing with a cane and taking more anti- inflammatories, along with the dangerous drugs she took to help keep the disease from worsening. -

Occupation Culture Art & Squatting in the City from Below

Minor Compositions Open Access Statement – Please Read This book is open access. This work is not simply an electronic book; it is the open access version of a work that exists in a number of forms, the traditional printed form being one of them. All Minor Compositions publications are placed for free, in their entirety, on the web. This is because the free and autonomous sharing of knowledges and experiences is important, especially at a time when the restructuring and increased centralization of book distribution makes it difficult (and expensive) to distribute radical texts effectively. The free posting of these texts does not mean that the necessary energy and labor to produce them is no longer there. One can think of buying physical copies not as the purchase of commodities, but as a form of support or solidarity for an approach to knowledge production and engaged research (particularly when purchasing directly from the publisher). The open access nature of this publication means that you can: • read and store this document free of charge • distribute it for personal use free of charge • print sections of the work for personal use • read or perform parts of the work in a context where no financial transactions take place However, it is against the purposes of Minor Compositions open access approach to: • gain financially from the work • sell the work or seek monies in relation to the distribution of the work • use the work in any commercial activity of any kind • profit a third party indirectly via use or distribution of the work • distribute in or through a commercial body (with the exception of academic usage within educational institutions) The intent of Minor Compositions as a project is that any surpluses generated from the use of collectively produced literature are intended to return to further the development and production of further publications and writing: that which comes from the commons will be used to keep cultivating those commons.