US in the World, Talking Global Issues With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boxing's Biggest Stars Collide on the Big Screen in "THE ONE: Floyd ‘Money' Mayweather Vs

July 30, 2013 Boxing's Biggest Stars Collide On The Big Screen In "THE ONE: Floyd ‘Money' Mayweather vs. Canelo Alvarez" Exciting Co-Main Event Features Danny Garcia and Lucas Matthysse NCM Fathom Events, Mayweather Promotions, Golden Boy Promotions, Canelo Promotions, SHOWTIME PPV® and O'Reilly Auto Parts Bring Long-Awaited Fights to Movie Theaters Nationwide Live from Las Vegas on Saturday, Sept. 14 CENTENNIAL, Colo.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Fans across the country can watch the much-anticipated match-up between the reigning boxing kings of the United States and Mexico when NCM Fathom Events, Mayweather Promotions, Golden Boy Promotions, Canelo Promotions, SHOWTIME PPV® and O'Reilly Auto Parts bring boxing's biggest star Floyd "Money" Mayweather and Super Welterweight World Champion Canelo Alvarez to the big screen. In what is anticipated to be one of the biggest fights in boxing history, both Mayweather and Canelo will defend their undefeated records in an action-packed, live broadcast from the MGM Grand Garden Arena in Las Vegas, Nev. on Mexican Independence Day weekend. "The One: Mayweather vs. Canelo" will be broadcast to select theaters nationwide on Saturday, Sept. 14 at 9:00 p.m. ET / 8:00 p.m. CT / 7:00 p.m. MT / 6:00 p.m. PT / 5:00 p.m. AK / 3:00 p.m. HI. In addition to the explosive main event, Unified Super Lightweight World Champion Danny "Swift" Garcia and WBC Interim Super Lightweight World Champion Lucas "The Machine" Matthysse will meet in a bout fans have been clamoring to see. Garcia vs. Matthysse will anchor the fight's undercard with additional bouts to be announced shortly. -

Remembering Katie Reich

THE M NARCH Volume 18 Number 1 • Serving the Archbishop Mitty Community • Oct 2008 Remembering Katie Reich Teacher, Mentor, Coach, Friend Katie Hatch Reich, beloved Biology and Environmental Science teacher and cross-country coach, was diagnosed with melanoma on April 1, 2008. She passed away peacefully at home on October 3, 2008. While the Mitty community mourns the loss of this loving teacher, coach, and friend, they also look back in remembrance on the profound infl uence Ms. Reich’s life had on them. “Katie’s passions were apparent to all “We have lost an angel on our campus. “My entire sophomore year, I don’t think “Every new teacher should be blessed to who knew her in the way she spoke, her Katie Reich was an inspiration and a mentor I ever saw Ms. Reich not smiling. Even after have a teacher like Katie Reich to learn from. hobbies, even her key chains. Her personal to many of our students. What bothers me is she was diagnosed with cancer, I remember Her mind was always working to improve key chain had a beetle that had been encased the fact that so many of our future students her coming back to class one day, jumping up lessons and try new things. She would do in acrylic. I recall her enthusiasm for it and will never have the opportunity to learn on her desk, crossing her legs like a little kid anything to help students understand biology wonder as she asked me, “Isn’t it beautiful?!” about biology, learn about our earth, or learn and asking us, “Hey! Anyone got any questions because she knew that only then could she On her work keys, Katie had typed up her about life from this amazing person. -

Mothers with Mental Illness: Public Health Nurses' Perspectives Patricia Bourrier University of Manitoba a Thesis Submitted T

Mothers with Mental Illness: Public Health Nurses’ Perspectives Patricia Bourrier University of Manitoba A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF NURSING Faculty of Nursing University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba February 3rd, 2011 Copyright © 2011 by Patricia Bourrier PHN PERSPECTIVES 2 PHN PERSPECTIVES 3 Table of Contents Page Acknowledgements ..............................................................................................................8 Abstract… ............................................................................................................................9 Chapter One: Introduction .............................................................................................10 Purpose of the Study ..........................................................................................................15 Healthy Child Development ..............................................................................................15 Conceptual Framework ......................................................................................................16 Research Questions ............................................................................................................17 Significance of the Study ...................................................................................................18 Chapter Two: Literature Review ...................................................................................19 -

Like UFC Champion Conor Mcgregor)

Achieve Your Goals Podcast #85 - How To Create Your Own Destiny (Like UFC Champion Conor McGregor) Nick: Welcome, to the Achieve Your Goals Podcast with Hal Elrod. I'm your host Nick Palkowski and you're listening to the show that is guaranteed to help you take your life to the next level faster than you ever thought possible. In each episode you'll learn from someone who has achieved extraordinary goals that most haven't. Is the author of number one best selling book The Miracle Morning, a hall of fame, and business achiever, and international keynote speaker, ultra marathon runner and the founder of vipsuccesscoaching.com. Mr. Hal Elrod. Hal: All right, Achieve Your Goals Podcast. Listeners welcome, this is your host Hal Elrod, and thank you for tuning in to what is sure to be an eye opening and surprisingly fun episode of the Achieve Your Goals Podcast. This will be a little different than anything we've ever done before. I do have a guest. I'm going to wait for a few minutes to tell you who that is. And the topic of the podcast today revolves around my favorite sport and specifically around the number one star, if you will. One of the top fighters in the world. And when it comes to my favorite sport, as many of you may know, I'm a huge fan of the sport known as M-M-A, which stands for Mixed Martial Arts, or what's popularly known as the UFC, which is the kind of the NBA of mix martial arts. -

Bma Presents 2019 Jazz in the Sculpture Garden Concerts

BMA PRESENTS 2019 JAZZ IN THE SCULPTURE GARDEN CONCERTS Tickets on sale June 5 for Vijay Iyer, Matana Roberts, and Wendel Patrick Quartet BALTIMORE, MD (May 2, 2018)—The Baltimore Museum of Art’s (BMA) popular summer jazz series returns with three concerts featuring national and regional talent in the museum’s lush gardens. Featured performers are Vijay Iyer (June 29), Matana Roberts (July 13), and the Wendel Patrick Quartet (July 27). General admission tickets are $50 for a single concert or $135 for the three-concert series. BMA Member tickets are $35 for a single concert or $90 for the three-concert series. Tickets are on sale Wednesday, June 5, and will sell out quickly, so reservations are highly recommended. Tickets for BMA Members are available beginning Wednesday, May 29. Saturday, June 29 – Vijay Iyer, jazz piano Grammy-nominated composer-pianist Vijay Iyer sees jazz as “creating beauty and changing the world” (NPR) and is recognized as “one of the best in the world at what he does.” (Pitchfork). Saturday, July 13 – Matana Roberts, experimental jazz saxophonist As “the spokeswoman for a new, politically conscious and refractory music scene” (Jazzthetik), Matana Roberts’ music has been praised for its “originality and … historic and social power” (music critic Peter Margasak). Saturday, July 27 – Wendel Patrick Quartet Wendel Patrick is the “wildly talented” (Baltimore Sun) alter ego of acclaimed classical and jazz pianist Kevin Gift. The Baltimore-based musician creates a unique blend of jazz, electronica, and hip hop. The BMA’s beautiful Janet and Alan Wurtzburger Sculpture Garden presents 19 early modernist works by artists such as Alexander Calder, Isamu Noguchi, and Auguste Rodin amidst a flagstone terrace and fountain. -

Cultural Orientation | Kurmanji

KURMANJI A Kurdish village, Palangan, Kurdistan Flickr / Ninara DLIFLC DEFENSE LANGUAGE INSTITUTE FOREIGN LANGUAGE CENTER 2018 CULTURAL ORIENTATION | KURMANJI TABLE OF CONTENTS Profile Introduction ................................................................................................................... 5 Government .................................................................................................................. 6 Iraqi Kurdistan ......................................................................................................7 Iran .........................................................................................................................8 Syria .......................................................................................................................8 Turkey ....................................................................................................................9 Geography ................................................................................................................... 9 Bodies of Water ...........................................................................................................10 Lake Van .............................................................................................................10 Climate ..........................................................................................................................11 History ...........................................................................................................................11 -

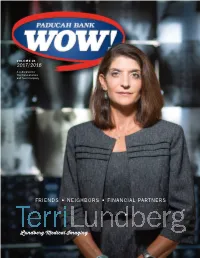

PB WOW 26 Magazine 2017

VOLUME 26 2017/2018 A publication for The Paducah Bank and Trust Company FRIENDS • NEIGHBORS • FINANCIAL PARTNERS Lundberg Medical Imaging PERSONAL or BUSINESS CREDITCARDS Choose the right credit card for you from someone you know and trust—PADUCAH BANK! VISIT WWW.PADUCAHBANK.COM TO APPLY TODAY! | lSA MEMBER FDIC 20 peekSneak Inside Volume 26 • 2017/2018 64 32 24 60 40 44 48 WOW! THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION FOR THE PADUCAH BANK AND TRUST COMPANY 555 JEFFERSON STREET • PO BOX 2600 • PADUCAH, KY 42002-2600 • 270.575.5700 • WWW.PADUCAHBANK.COM • FIND US ON FACEBOOK ON THE COVER: TERRI LUNDBERG, LUNDBERG MEDICAL IMAGING. PHOTOGRAPHY BY GLENN HALL. IF YOU HAVE QUESTIONS ABOUT A PRODUCT OR SERVICE OR WOULD LIKE TO OBTAIN A COPY OF PADUCAH BANK’S WOW!, CONTACT SUSAN GUESS AT 270.575.5723 OR [email protected]. MEMBER FDIC OUR TEAM HAS THE EXPERTISE TO HELP YOU MANAGE EVERY ASPECT OF YOUR COMMERCIAL BANKING RELATIONSHIP Here’s why WE know YOU should work with US! Paducah Bank has years of providing QUALITY SERVICE in commercial banking and demonstrates this EXPERIENCE in meeting the needs of your entire commercial relationship. With CREATIVE SOLUTIONS for borrowing and depository to treasury management and employee benefits, our commercial relationship managers will provide a QUICK RESPONSE to help you spend time focusing on your business and let us take care of your banking! G} !GUAI.HOUIING PADUCAH BANK. Bank. Borrow. Succeed in business. | www.paducahbank.com MEMBER FDIC LENDER TERRY BRADLEY • CHASE VENABLE • SARAH SUITOR • TOM CLAYTON • BLAKE VANDERMEULEN • DIANA QUESADA • ALAN SANDERS DEARfriends We’re quickly closing in on another banner year for Paducah and for Paducah Bank. -

List of Merchants 4

Merchant Name Date Registered Merchant Name Date Registered Merchant Name Date Registered 9001575*ARUBA SPA 05/02/2018 9013807*HBC SRL 05/02/2018 9017439*FRATELLI CARLI SO 05/02/2018 9001605*AGENZIA LAMPO SRL 05/02/2018 9013943*CASA EDITRICE LIB 05/02/2018 9017440*FRATELLI CARLI SO 05/02/2018 9003338*ARUBA SPA 05/02/2018 9014076*MAILUP SPA 05/02/2018 9017441*FRATELLI CARLI SO 05/02/2018 9003369*ARUBA SPA 05/02/2018 9014276*CCS ITALIA ONLUS 05/02/2018 9017442*FRATELLI CARLI SO 05/02/2018 9003946*GIUNTI EDITORE SP 05/02/2018 9014368*EDITORIALE IL FAT 05/02/2018 9017574*PULCRANET SRL 05/02/2018 9004061*FREDDY SPA 05/02/2018 9014569*SAVE THE CHILDREN 05/02/2018 9017575*PULCRANET SRL 05/02/2018 9004904*ARUBA SPA 05/02/2018 9014616*OXFAM ITALIA 05/02/2018 9017576*PULCRANET SRL 05/02/2018 9004949*ELEMEDIA SPA 05/02/2018 9014762*AMNESTY INTERNATI 05/02/2018 9017577*PULCRANET SRL 05/02/2018 9004972*ARUBA SPA 05/02/2018 9014949*LIS FINANZIARIA S 05/02/2018 9017578*PULCRANET SRL 05/02/2018 9005242*INTERSOS ASSOCIAZ 05/02/2018 9015096*FRATELLI CARLI SO 05/02/2018 9017676*PIERONI ROBERTO 05/02/2018 9005281*MESSAGENET SPA 05/02/2018 9015228*MEDIA SHOPPING SP 05/02/2018 9017907*ESITE SOCIETA A R 05/02/2018 9005607*EASY NOLO SPA 05/02/2018 9015229*SILVIO BARELLO 05/02/2018 9017955*LAV LEGA ANTIVIVI 05/02/2018 9006680*PERIODICI SAN PAO 05/02/2018 9015245*ASSURANT SERVICES 05/02/2018 9018029*MEDIA ON SRL 05/02/2018 9007043*INTERNET BOOKSHOP 05/02/2018 9015286*S.O.F.I.A. -

Copyrighted Material

1 The Best of Japan Long ago, Japanese ranked the three best of almost every natural wonder and attraction in their country: the three best gardens, the three best scenic spots, the three best waterfalls, even the three best bridges. But choosing the “best” of anything is inherently subjective, and decades—even centuries—have passed since some of the original “three best” were so designated. Still, lists can be useful for establishing priorities. To help you get the most out of your stay, I’ve compiled this list of what I consider the best Japan has to offer based on years of traveling through the country. From the weird to the wonderful, the profound to the profane, the obvious to the obscure, these recom- mendations should fire your imagination and launch you toward discoveries of your own. 1 THE BEST TRAVEL EXPERIENCES • Making a Pilgrimage to a Temple or then soaking in near-scalding waters. Shrine: From mountaintop shrines to Hot-spring spas are located almost neighborhood temples, Japan’s religious everywhere in Japan, from Kyushu to structures rank among the nation’s most Hokkaido; see the “Bathing” section popular attractions. Usually devoted to under “Minding Your P’s & Q’s” in a particular deity, they’re visited for chapter 2, and the regional chapters for specific reasons: Shopkeepers call on more information. Fushimi-Inari Shrine outside Kyoto, • Participating in a Festival: With Shin- dedicated to the goddess of rice and toism and Buddhism as its major reli- therefore prosperity, while couples gions, and temples and shrines virtually wishing for a happy marriage head to everywhere, Japan has multiple festivals Kyoto’s Jishu Shrine, a shrine to the every week. -

The Top 365 Wrestlers of 2019 Is Aj Styles the Best

THE TOP 365 WRESTLERS IS AJ STYLES THE BEST OF 2019 WRESTLER OF THE DECADE? JANUARY 2020 + + INDY INVASION BIG LEAGUES REPORT ISSUE 13 / PRINTED: 12.99$ / DIGITAL: FREE TOO SWEET MAGAZINE ISSUE 13 Mohammad Faizan Founder & Editor in Chief _____________________________________ SENIOR WRITERS.............Nick Whitworth ..........................................Tom Yamamoto ......................................Santos Esquivel Jr SPECIAL CONTRIBUTOR....…Chuck Mambo CONTRIBUTING WRITERS........Matt Taylor ..............................................Antonio Suca ..................................................7_year_ish ARTIST………………………..…ANT_CLEMS_ART PHOTOGRAPHERS………………...…MGM FOTO .........................................Pw_photo2mass ......................................art1029njpwphoto ..................................................dasion_sun ............................................Dragon000stop ............................................@morgunshow ...............................................photosneffect ...........................................jeremybelinfante Content Pg.6……………….……...….TSM 100 Pg.28.………….DECADE AWARDS Pg.29.……………..INDY INVASION Pg.32…………..THE BIG LEAGUES THE THOUGHTS EXPRESSED IN THE MAGAZINE IS OF THE EDITOR, WRITERS, WRESTLERS & ADVERTISERS. THE MAGAZINE IS NOT RELATED TO IT. ANYTHING IN THIS MAGAZINE SHOULD NOT BE REPRODUCED OR COPIED. TSM / SEPT 2019 / 2 TOO SWEET MAGAZINE ISSUE 13 First of all I’ll like to praise the PWI for putting up a 500 list every year, I mean it’s a lot of work. Our team -

Origins of Canadian Olympic Weightlifting

1 Page # June 30, 2011. ORIGINS OF CANADIAN OLYMPIC WEIGHTLIFTING INTRODUCTION The author does not pretend to have written everything about the history of Olympic weightlifting in Canada since Canadian Weightlifting has only one weightlifting magazine to refer to and it is from the Province of Québec “Coup d’oeil sur l’Haltérophilie”, it is understandable that a great number of the articles are about the Quebecers. The researcher is ready to make any modification to this document when it is supported by facts of historical value to Canadian Weightlifting. (Ce document est aussi disponible en langue française) The early history of this sport is not well documented, but weightlifting is known to be of ancient origin. According to legend, Egyptian and Chinese athletes demonstrated their strength by lifting heavy objects nearly 5,000 years ago. During the era of the ancient Olympic Games a Greek athlete of the 6th century BC, Milo of Crotona, gained fame for feats of strength, including the act of lifting an ox onto his shoulders and carrying it the full length of the stadium at Olympia, a distance of more than 200 meters. For centuries, men have been interested in strength, while also seeking athletic perfection. Early strength competitions, where Greek athletes lifted bulls or where Swiss mountaineers shouldered and tossed huge boulders, gave little satisfaction to those individuals who wished to demonstrate their athletic ability. During the centuries that followed, the sport continued to be practiced in many parts of the world. Weightlifting in the early 1900s saw the development of odd-shaped dumbbells and kettle bells which required a great deal of skill to lift, but were not designed to enable the body’s muscles to be used efficiently. -

We Have the Power

We Have the Power Realizing clean, renewable energy’s potential to power America We Have the Power Realizing clean, renewable energy’s potential to power America Written by: Gideon Weissman, Frontier Group Emma Searson, Environment America Research & Policy Center June 2021 Acknowledgments The authors thank Steven Nadel of the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, Dmitrii Bogdanov of the Lappeenranta University of Technology, Charles Eley of Architecture 2030, Karl Rábago of Rábago Energy, and Ben Hellerstein of Environment Massachusetts Research and Policy Center for their review of drafts of this document, as well as their insights and suggestions. Thanks also to Susan Rakov, Tony Dutzik, Bryn Huxley-Re- icher and Jamie Friedman of Frontier Group for editorial support. Environment America Research & Policy Center thanks the Bydale Foundation, Energy Foundation and all who provided funding to make this report possible. The recommendations are those of Environment America Research & Policy Center. The authors bear responsibility for any factual errors. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders or those who provided review. 2021 Environment America Research & Policy Center. Some Rights Reserved. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 3.0 Unported License. To view the terms of this license, visit creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0. Environment America Research & Policy Center is a 501(c)(3) organization. We are dedicated to protecting our air, water and open spaces. We investigate problems, craft solutions, educate the public and decision-makers, and help the public make their voices heard in local, state and national debates over the quality of our environment and our lives.