The Terror Experts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Remembering Katie Reich

THE M NARCH Volume 18 Number 1 • Serving the Archbishop Mitty Community • Oct 2008 Remembering Katie Reich Teacher, Mentor, Coach, Friend Katie Hatch Reich, beloved Biology and Environmental Science teacher and cross-country coach, was diagnosed with melanoma on April 1, 2008. She passed away peacefully at home on October 3, 2008. While the Mitty community mourns the loss of this loving teacher, coach, and friend, they also look back in remembrance on the profound infl uence Ms. Reich’s life had on them. “Katie’s passions were apparent to all “We have lost an angel on our campus. “My entire sophomore year, I don’t think “Every new teacher should be blessed to who knew her in the way she spoke, her Katie Reich was an inspiration and a mentor I ever saw Ms. Reich not smiling. Even after have a teacher like Katie Reich to learn from. hobbies, even her key chains. Her personal to many of our students. What bothers me is she was diagnosed with cancer, I remember Her mind was always working to improve key chain had a beetle that had been encased the fact that so many of our future students her coming back to class one day, jumping up lessons and try new things. She would do in acrylic. I recall her enthusiasm for it and will never have the opportunity to learn on her desk, crossing her legs like a little kid anything to help students understand biology wonder as she asked me, “Isn’t it beautiful?!” about biology, learn about our earth, or learn and asking us, “Hey! Anyone got any questions because she knew that only then could she On her work keys, Katie had typed up her about life from this amazing person. -

Mothers with Mental Illness: Public Health Nurses' Perspectives Patricia Bourrier University of Manitoba a Thesis Submitted T

Mothers with Mental Illness: Public Health Nurses’ Perspectives Patricia Bourrier University of Manitoba A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF NURSING Faculty of Nursing University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba February 3rd, 2011 Copyright © 2011 by Patricia Bourrier PHN PERSPECTIVES 2 PHN PERSPECTIVES 3 Table of Contents Page Acknowledgements ..............................................................................................................8 Abstract… ............................................................................................................................9 Chapter One: Introduction .............................................................................................10 Purpose of the Study ..........................................................................................................15 Healthy Child Development ..............................................................................................15 Conceptual Framework ......................................................................................................16 Research Questions ............................................................................................................17 Significance of the Study ...................................................................................................18 Chapter Two: Literature Review ...................................................................................19 -

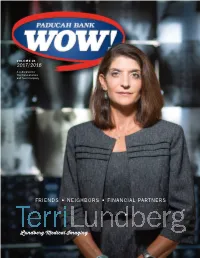

PB WOW 26 Magazine 2017

VOLUME 26 2017/2018 A publication for The Paducah Bank and Trust Company FRIENDS • NEIGHBORS • FINANCIAL PARTNERS Lundberg Medical Imaging PERSONAL or BUSINESS CREDITCARDS Choose the right credit card for you from someone you know and trust—PADUCAH BANK! VISIT WWW.PADUCAHBANK.COM TO APPLY TODAY! | lSA MEMBER FDIC 20 peekSneak Inside Volume 26 • 2017/2018 64 32 24 60 40 44 48 WOW! THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION FOR THE PADUCAH BANK AND TRUST COMPANY 555 JEFFERSON STREET • PO BOX 2600 • PADUCAH, KY 42002-2600 • 270.575.5700 • WWW.PADUCAHBANK.COM • FIND US ON FACEBOOK ON THE COVER: TERRI LUNDBERG, LUNDBERG MEDICAL IMAGING. PHOTOGRAPHY BY GLENN HALL. IF YOU HAVE QUESTIONS ABOUT A PRODUCT OR SERVICE OR WOULD LIKE TO OBTAIN A COPY OF PADUCAH BANK’S WOW!, CONTACT SUSAN GUESS AT 270.575.5723 OR [email protected]. MEMBER FDIC OUR TEAM HAS THE EXPERTISE TO HELP YOU MANAGE EVERY ASPECT OF YOUR COMMERCIAL BANKING RELATIONSHIP Here’s why WE know YOU should work with US! Paducah Bank has years of providing QUALITY SERVICE in commercial banking and demonstrates this EXPERIENCE in meeting the needs of your entire commercial relationship. With CREATIVE SOLUTIONS for borrowing and depository to treasury management and employee benefits, our commercial relationship managers will provide a QUICK RESPONSE to help you spend time focusing on your business and let us take care of your banking! G} !GUAI.HOUIING PADUCAH BANK. Bank. Borrow. Succeed in business. | www.paducahbank.com MEMBER FDIC LENDER TERRY BRADLEY • CHASE VENABLE • SARAH SUITOR • TOM CLAYTON • BLAKE VANDERMEULEN • DIANA QUESADA • ALAN SANDERS DEARfriends We’re quickly closing in on another banner year for Paducah and for Paducah Bank. -

The Best of the 2014 Cicero Speechwriting Awards

1 VITAL SPEECHES of the day 2014 EDITION THESE VITAL SPEECHES the best of the 2014 cicero speechwriting awards 58 “Why Water Cooperation Is Essential to the Future of Our World” by Jan Sonneveld GRAND AWard 2 “Pick Me” by Richard Newman, Director of UK Body Talk Ltd. 59 “Inventing Our Future” by Aaron Hoover CATEGORY WINNERS 4 “Social and Policy Implications of an Aging Society” HONORABLE MENTION by Boe Workman “Rebuilding the Middle Class: A Blueprint for the Future” by Boe Workman for A. Barry Rand, CEO, AARP 9 “We Are the Cavalry” by Janet Harrell “1888 All Over Again” by Mark Lucius, for John Schlifske, CEO, 12 “Write Your Own Story” by Aaron Hoover Northwestern Mutual 14 “Getting the Future Energy Mix Right: How the American Shale “Sharing Knowledge with Abandon” by Kim Clarke, for Mary Sue Revolution Is Changing the World” by Brian Akre Coleman, President, University of Michigan 17 “Climate Change and the Story of Sarah” by Rune Kier Nielsen “Leading Lives That Matter” by Elaine A. Tooley, for Nathan Hatch, President, Wake Forest University 18 “The Theory of Everything” by Jared Bloom “Challenging Opportunities: The U.S., Russia and the World’s 19 “Power” by Daniel Rose Energy Journey” by John Barnes, for Robert W. Dudley, Group Chief Executive, BP 20 “Moving Electric Ahead” by Doug Neff “A New Beginning” by Jan Sonneveld, for Melanie Schultz van 21 “The Face of Intolerance” by Suzanne Levy Haegen, Minister of Infrastructure and the Environment, the Netherlands 22 “Turnaround: Third World Lessons for First World Growth” by Greta Stahl “Clearing Barriers to Global Trade” by Bill Bryant, for David Abney, COO, UPS 22 “Connecting Education to Home, School and Community” by David Bradley “Taking the Diversity Challenge” by Trey Brown, for Stephanie O’Sullivan, Principal Deputy Director of National Intelligence, 25 “Electronic Threats to Humane Health Care” by Stephen Bertman United States 30 “Real Entrepreneurs Don’t Go It Alone” by Teresa Zumwald “Reshaping the Box: Breakthrough Thinking About Diversity” by Janet Harrell, for Forest T. -

The Affordable Care Act Health Exchange Is Open Rathbun Insurance Is Available to Help with Information and Enrollment Assistance

FREE a newspaper for the rest of us www.lansingc November 12-18, 2014 a newspaper for the rest of us www.lansingcitypulse.com BRIGHT AND SHINY LOVE,LOVE, ITALIANITALIAN STYLESTYLE Will the luster of the Red Longtime Roma Bakery owner Cedar Renaissance help finally dishes out recipes with Lansing's east side?...p. 5 new cookbook...p. 18 The Affordable Care Act Health Exchange is Open Rathbun Insurance is available to help with information and enrollment assistance. (517) 482-1316 www.rathbunagency.com 2 www.lansingcitypulse.com City Pulse • November 12, 2014 10 Every Saturday THIS WEEK: Red Cedar Renaissance THIS WEEK: State Legislature Hosted by Newsmakers Berl Schwartz Craft Beer, Spirits & Grub! $3 OFF Large Plates *Lunch only Lunches $5-$7 after discount. Good for Burger & Fries, Fish & Chips and much more. Mon-Fri., 11 a.m.-3p.m. Good Thru Nov. 30, 2014 Drink & food specials during Wings, Spartans and Joel Ferguson Robert Trezise Jr. Pat Lindemann Pistons games! Developer President/CEO Lansing Economic Area Partnership (LEAP) Ingham County Drain Commissioner Hours: Sun-Wed. 11:30 a.m.-Midnight Thurs.-Sat. 11:30 a.m.-2 a.m. 3415 E. Saginaw North of Frandor at the split, in the North Point Mall (517) 333-8215 Watch past episodes at vimeo.com/channels/citypulse www.front43pub.com City Pulse • November 12, 2014 www.lansingcitypulse.com 3 4 www.lansingcitypulse.com City Pulse • November 12, 2014 Feedback VOL. 14 Lawrence Cosentino did an back all the wonderful memories asso- ISSUE 13 AMAZING story on the Knapp's build- ciated with that unique store. -

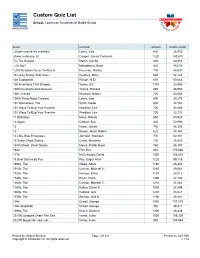

Custom Quiz List

Custom Quiz List School: Coachman Fundamental Middle School MANAGEMENT BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® WORD COUNT ¿Quién cuenta las estrellas? Lowry, Lois 680 26,950 último mohicano, El Cooper, James Fenimore 1220 140,610 'Tis The Season Martin, Ann M. 890 40,955 ...Or Not? Mandabach, Brian 840 98,676 1,000 Reasons Never To Kiss A Freeman, Martha 790 58,937 10 Lucky Things That Have Hershey, Mary 640 52,124 100 Cupboards Wilson, N. D. 650 59,063 100 Inventions That Shaped... Yenne, Bill 1370 33,959 1000 Questions And Answers Tames, Richard 890 38,950 1001 Cranes Hirahara, Naomi 720 43,080 100th Thing About Caroline Lowry, Lois 690 30,273 101 Dalmatians, The Smith, Dodie 830 44,767 101 Ways To Bug Your Parents Wardlaw, Lee 700 37,864 101 Ways To Bug Your Teacher Wardlaw, Lee 700 52,733 11 Birthdays Mass, Wendy 650 50,929 12 Again Corbett, Sue 800 52,996 13 Howe, James 740 56,355 13 Brown, Jason Robert 620 38,363 13 Little Blue Envelopes Johnson, Maureen 770 62,401 13 Scary Ghost Stories Carus, Marianne 730 25,560 145th Street: Short Stories Myers, Walter Dean 760 36,397 1632 Flint, Eric 650 175,646 1776 McCullough, David 1300 105,034 18 Best Stories By Poe Poe, Edgar Allan 1220 99,118 1900s, The Woog, Adam 1160 26,484 1910s, The Uschan, Michael V. 1280 29,561 1920s, The Hanson, Erica 1170 28,812 1930s, The Press, Petra 1300 27,749 1940s, The Uschan, Michael V. 1210 31,665 1950s, The Kallen, Stuart A. -

![Make the Right Thing [Entire Talk]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5223/make-the-right-thing-entire-talk-2715223.webp)

Make the Right Thing [Entire Talk]

Stanford eCorner Make the Right Thing [Entire Talk] Alberto Savoia, Google 13-03-2019 URL: https://ecorner.stanford.edu/video/make-the-right-thing-entire-talk/ As Google’s first engineering director, Alberto Savoia led the team that launched Google’s revolutionary AdWords project. After founding two startups, he returned to Google in 2008 and he assumed the role of “Innovation Agitator,” developing trainings and workshops to catalyze smart, impactful creation within the company. Drawing on his book The Right It, he begins with the premise that at least 80 percent of innovations fail, even if competently executed. He discusses how to reframe the central challenge of innovation as a question not of skill or technology, but of market demand: Will anyone actually care? Savoia shares strategies for winning the fight against failure, by using a rapid-prototyping technique he calls “pretotyping.” Transcript (Techno music) - [Announcer] Who you are defines how you build.. (techno music) - [Alberto] This is my battle cry these days, failure bites, bite back.. I'm a serial entrepreneur, and I kind of got my butt kicked a few times and the last time I decided I don't want this to ever happen again to me, or anyone else.. My mission to help entrepreneurs, most of you here, to teach you how to fight failure and win consistently.. But first, let me tell you, I'm gonna structure it very simply, seven strategies in 35 minutes.. I don't have a lot of time, but fortunately, there is a book that you can buy out there that, you know, you can spend six hour in my company. -

Miss Lewis County Crowned Chehalis Teen Wins Annual Scholarship Pageant / Main 3

$1 Tuesday, March 12, 2013 Reaching 110,000 Readers in Print and Online — www.chronline.com 2013 All-Area Girls Basketball W.F. West’s Jamika Parker Named Most Valuable Player / Sports 1 Swinging Away Pot for High School Baseball Season Begins / Sports Toddler Centralia Police Arrest Couple for Allowing Child to Inhale Marijuana / Main 4 Miss Lewis County Crowned Chehalis Teen Wins Annual Scholarship Pageant / Main 3 Holly Pederson / For The Chronicle Newly crowned Miss Lewis County Abrielle Sheets, 18, Chehalis, greets the audience at the 51st annual Miss Lewis County Pageant Saturday night in Chehalis. Business Expands Coming to America Sasquatch Talk Centralia College Instructor Sponsoring Former Investigator Discusses Bigfoot at Centralia Chehalis-Based Sandrini Construction Now in Afghani Translator / Main 12 Library / Main 5 the Restoration Business / Main 7 The Chronicle, Serving The Greater Weather No Joke Deaths Lewis County Area Since 1889 TONIGHT: Low 45 Tenino Mayor McCann, Lois Hayton, Follow Us on Twitter TOMORROW: High 57 99, Panorama City @chronline Rain Likely Announces Rains, Gwendolyn N., see details on page Main 2 Plans for 75, Onalaska Find Us on Facebook Standup McCain, Emma J., 79, www.facebook.com/ Weather picture by Tyler Glenoma thecentraliachronicle Stilphen, third grade, Comedy Career Morton Elementary / Main 14 Main 2 The Chronicle, Centralia/Chehalis, Wash., Tuesday, March 12, 2013 COMMUNITY CALENDAR / WEATHER Community Calendar Editor’s Best Bet Today WHAT’S HAPPENING? Bingo, Chehalis Moose Lodge, doors open at 4:30 p.m., game starts If you have an event you at 6:30 p.m.; food available, (360) would like included in the 736-9030 Community Calendar, please Energy efficiency forum, 7 p.m., email your information to Mossyrock Community Center, pre- [email protected]. -

The Art of Living - the Marketing of Identity Through Nationality and Spirituality

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2005 The ra t of living - the marketing of identity through nationality and spirituality Shirisha Shankar Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Shankar, Shirisha, "The ra t of living - the marketing of identity through nationality and spirituality" (2005). LSU Master's Theses. 471. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/471 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ART OF LIVING - THE MARKETING OF IDENTITY THROUGH NATIONALITY AND SPIRITUALITY A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In The Department of Geography and Anthropology By Shirisha Shankar B.A., St.Joseph’s College of Arts and Science, 1999 M.S., Bangalore University,2001 May 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I gratefully acknowledge and thank my committee members Dr. Helen Regis, Dr. Miles Richardson and Dr. Gail Sutherland for their valuable time, patience, enthusiasm, encouragement and comments. I particularly appreciate Dr. Helen Regis for giving me the opportunity to work with her as Graduate Assistant. Special thanks to the participants of the courses I took at the Art of Living and all others who were willing participants for talking to me and sharing with me freely their life stories and comments about spirituality and life in general. -

Congressional Record—Senate S1746

S1746 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE March 24, 2021 no time to waste. We are going to need Grassley Marshall Scott (FL) Cornyn King Rubio all the help we can get, particularly Hagerty McConnell Scott (SC) Cortez Masto Klobuchar Sanders Hassan Menendez Shaheen Cotton Lankford Sasse from experts like Dr. Murthy and Dr. Heinrich Merkley Shelby Cramer Leahy Schatz Levine to get it done. Hickenlooper Moran Sinema Crapo Lee Schumer I yield the floor. Hirono Murkowski Smith Daines Luja´ n Scott (FL) Hoeven Murphy Stabenow Duckworth Lummis Scott (SC) VOTE ON LEVINE NOMINATION Hyde-Smith Murray Sullivan Durbin Manchin Shaheen Inhofe Ossoff Ernst Markey Shelby The PRESIDING OFFICER. The Tester Johnson Padilla Feinstein Marshall Sinema Thune question is, Will the Senate advise and Kaine Peters Fischer McConnell Smith Tillis consent to the Levine nomination? Kelly Portman Gillibrand Menendez Stabenow Mrs. MURRAY. I ask for the yeas and Kennedy Reed Toomey Graham Merkley Sullivan Tuberville nays. King Risch Grassley Moran Tester Klobuchar Romney Van Hollen Hagerty Murkowski Thune The PRESIDING OFFICER. Is there a Lankford Rosen Warner Hassan Murphy Tillis sufficient second? Leahy Rounds Warnock Heinrich Murray Toomey There appears to be a sufficient sec- Lee Rubio Warren Hickenlooper Ossoff Tuberville Luja´ n Sanders Whitehouse Hirono Padilla Van Hollen ond. Lummis Sasse Wicker Hoeven Peters Warner The clerk will call the roll. Manchin Schatz Wyden Hyde-Smith Portman Warnock The bill clerk called the roll. Markey Schumer Young Inhofe Reed Warren The result was announced—yeas 52, Johnson Risch Whitehouse NAYS—2 Kaine Romney Wicker nays 48, as follows: Hawley Paul Kelly Rosen Wyden [Rollcall Vote No. -

RML Spring 2021 Rights Guide

NON-FICTION TO STAND AND STARE: How To Garden While Doing Next to Nothing Andrew Timothy O’Brien There’s a lot of advice out there that would tell you how to do numerous things in your garden. But not so much that invites you to think about how to be while you’re out there. With increasingly busy lives, yet another list of chores seems like the very last thing any of us needs when it comes to our own practice of self-care, relaxation and renewal. After all, aren’t these the things we wanted to escape to the garden for in the first place? Put aside the ‘Jobs to do this week’ section in the Sunday papers. What if there were a more low-intervention way to On submission Spring 2021 garden, some reciprocal arrangement through which both you and your soil get fed, with the minimum degree of fuss, effort and guilt on your part, and the maximum measure of healthy, organic growth on that of your garden? In To Stand and Stare, Andrew Timothy O’Brien weaves together strands of botany, philosophy and mindfulness to form an ecological narrative suffused with practical gardening know-how. Informed by a deep understanding and appreciation of natural processes, O’Brien encourages the reader to think from the ground up, as we follow the pattern of a plant’s growth through the season – roots, shoots, and fruits – while advocating an increased awareness of our surroundings. ANDREW TIMOTHY O’BRIEN is an online gardening coach, blogger and host of the critically acclaimed Gardens, Weeds & Words podcast. -

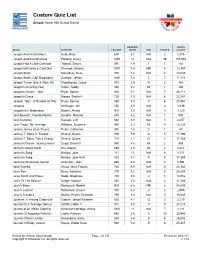

Custom Quiz List

Custom Quiz List School: Forest Hills School District MANAGEMENT READING WORD BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® LEVEL GRL POINTS COUNT Joseph And His Brothers Auld, Mary 690 4.1 N/A 2 1,376 Joseph Andrews/Shamela Fielding, Henry 1200 12 N/A 39 165,998 Joseph Had A Little Overcoat Taback, Simms BR 1.9 I 1 182 Joseph McCarthy & Cold War Sherrow, Victoria 1070 7.4 NR 6 13,397 Joseph Stalin McCollum, Sean 970 7.6 N/A 6 13,030 Joseph Stalin (A&E Biography) Zuehlke, Jeffrey 1030 7.4 Z 7 17,172 Joseph Turner (Life & Work Of) Woodhouse, Jayne 470 2.5 N 2 764 Joseph's Amazing Coat Slater, Teddy 480 3.2 M 1 455 Joseph's Choice - 1861 Pryor, Bonnie 630 5.1 N/A 7 26,711 Joseph's Grace Moses, Shelia P. 730 5.5 N/A 8 22,241 Joseph: 1861 - A Rumble Of War Pryor, Bonnie 680 5.3 V 6 27,451 Josepha McGugan, Jim 550 3.5 N/A 2 1,339 Josephine's 'Magination Dobrin, Arnold N/A 3.5 N/A 3 3,129 Josh Beckett...Florida Marlins Sandler, Michael 680 4.2 N/A 1 994 Josh Hamilton Savage, Jeff 660 3.8 N/A 3 2,257 Josh Taylor, Mr. Average Williams, Suzanne 580 3.3 M 5 10,233 Joshua James Likes Trucks Petrie, Catherine BR 1.4 C 1 47 Joshua T. Bates In Trouble... Shreve, Susan 890 5.9 Q 5 17,196 Joshua T. Bates Takes Charge Shreve, Susan 710 4.1 Q 4 17,468 Joshua's Dream: Journey-Israel Segal, Sheila F.