The Service of the 320Th Service Battalion the Backbone of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Western Front the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Westernthe Front

Ed 2 June 2015 2 June Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 1 The Western Front The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Western Front The Western Creative Media Design ADR003970 Edition 2 June 2015 The Somme Battlefield: Newfoundland Memorial Park at Beaumont Hamel Mike St. Maur Sheil/FieldsofBattle1418.org The Somme Battlefield: Lochnagar Crater. It was blown at 0728 hours on 1 July 1916. Mike St. Maur Sheil/FieldsofBattle1418.org The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 1 The Western Front 2nd Edition June 2015 ii | THE WESTERN FRONT OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR ISBN: 978-1-874346-45-6 First published in August 2014 by Creative Media Design, Army Headquarters, Andover. Printed by Earle & Ludlow through Williams Lea Ltd, Norwich. Revised and expanded second edition published in June 2015. Text Copyright © Mungo Melvin, Editor, and the Authors listed in the List of Contributors, 2014 & 2015. Sketch Maps Crown Copyright © UK MOD, 2014 & 2015. Images Copyright © Imperial War Museum (IWM), National Army Museum (NAM), Mike St. Maur Sheil/Fields of Battle 14-18, Barbara Taylor and others so captioned. No part of this publication, except for short quotations, may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the permission of the Editor and SO1 Commemoration, Army Headquarters, IDL 26, Blenheim Building, Marlborough Lines, Andover, Hampshire, SP11 8HJ. The First World War sketch maps have been produced by the Defence Geographic Centre (DGC), Joint Force Intelligence Group (JFIG), Ministry of Defence, Elmwood Avenue, Feltham, Middlesex, TW13 7AH. United Kingdom. -

ABBN-Final.Pdf

RESTRICTED CONTENTS SERIAL 1 Page 1. Introduction 1 - 4 2. Sri Lanka Army a. Commands 5 b. Branches and Advisors 5 c. Directorates 6 - 7 d. Divisions 7 e. Brigades 7 f. Training Centres 7 - 8 g. Regiments 8 - 9 h. Static Units and Establishments 9 - 10 i. Appointments 10 - 15 j. Rank Structure - Officers 15 - 16 k. Rank Structure - Other Ranks 16 l. Courses (Local and Foreign) All Arms 16 - 18 m. Course (Local and Foreign) Specified to Arms 18 - 21 SERIAL 2 3. Reference Points a. Provinces 22 b. Districts 22 c. Important Townships 23 - 25 SERIAL 3 4. General Abbreviations 26 - 70 SERIAL 4 5. Sri Lanka Navy a. Commands 71 i RESTRICTED RESTRICTED b. Classes of Ships/ Craft (Units) 71 - 72 c. Training Centres/ Establishments and Bases 72 d. Branches (Officers) 72 e. Branches (Sailors) 73 f. Branch Identification Prefix 73 - 74 g. Rank Structure - Officers 74 h. Rank Structure - Other Ranks 74 SERIAL 5 6. Sri Lanka Air Force a. Commands 75 b. Directorates 75 c. Branches 75 - 76 d. Air Force Bases 76 e. Air Force Stations 76 f. Technical Support Formation Commands 76 g. Logistical and Administrative Support Formation Commands 77 h. Training Formation Commands 77 i. Rank Structure Officers 77 j. Rank Structure Other Ranks 78 SERIAL 6 7. Joint Services a. Commands 79 b. Training 79 ii RESTRICTED RESTRICTED INTRODUCTION USE OF ABBREVIATIONS, ACRONYMS AND INITIALISMS 1. The word abbreviations originated from Latin word “brevis” which means “short”. Abbreviations, acronyms and initialisms are a shortened form of group of letters taken from a word or phrase which helps to reduce time and space. -

MAJOR GENERAL RAYMOND F. REES the Adjutant General, Oregon National Guard

MAJOR GENERAL RAYMOND F. REES The Adjutant General, Oregon National Guard Major General Raymond F. Rees assumed duties as The Adjutant General for Oregon on July 1, 2005. He is responsible for providing the State of Oregon and the United States with a ready force of citizen soldiers and airmen, equipped and trained to respond to any contingency, natural or manmade. He directs, manages, and supervises the administration, discipline, organization, training and mobilization of the Oregon National Guard, the Oregon State Defense Force, the Joint Force Headquarters and the Office of Oregon Emergency Management. He is also assigned as the Governor’s Homeland Security Advisor. He develops and coordinates all policies, plans and programs of the Oregon National Guard in concert with the Governor and legislature of the State. He began his military career in the United States Army as a West Point cadet in July 1962. Prior to his current assignment, Major General Rees had numerous active duty and Army National Guard assignments to include: service in the Republic of Vietnam as a cavalry troop commander; commander of the 116th Armored Calvary Regiment; nearly nine years as the Adjutant General of Oregon; Director of the Army National Guard, National Guard Bureau; over five years service as Vice Chief, National Guard Bureau; 14 months as Acting Chief, National Guard Bureau; Chief of Staff (dual-hatted), Headquarters North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) and United States Northern Command (USNORTHCOM). NORAD is a binational, Canada and United States command. EDUCATION: US Military Academy, West Point, New York, BS University of Oregon, JD (Law) Command and General Staff College (Honor Graduate) Command and General Staff College, Pre-Command Course Harvard University Executive Program in National and International Security Senior Reserve Component Officer Course, United States Army War College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania 1 ASSIGNMENTS: 1. -

Page 20 TITLE 32—NATIONAL GUARD § 314 § 314

§ 314 TITLE 32—NATIONAL GUARD Page 20 CROSS REFERENCES AMENDMENTS Army National Guard of United States and Air Na- 1991—Subsec. (b). Pub. L. 102–190 struck out ‘‘each tional Guard of United States, enlistment, see section Territory and’’ before ‘‘the District of Columbia’’ in 12107 of Title 10, Armed Forces. first sentence, and struck out at end ‘‘To be eligible for appointment as adjutant general of a Territory, a per- SECTION REFERRED TO IN OTHER SECTIONS son must be a citizen of that jurisdiction.’’ This section is referred to in title 10 section 311. 1990—Subsec. (d). Pub. L. 101–510 struck out at end ‘‘Each Secretary shall send with his annual report to § 314. Adjutants general Congress an abstract of the returns and reports of the (a) There shall be an adjutant general in each adjutants general and such comments as he considers necessary for the information of Congress.’’ State and Territory, Puerto Rico, and the Dis- 1988—Subsec. (a). Pub. L. 100–456, § 1234(b)(1), struck trict of Columbia. He shall perform the duties out ‘‘the Canal Zone,’’ after ‘‘Puerto Rico,’’. prescribed by the laws of that jurisdiction. Subsec. (b). Pub. L. 100–456, § 1234(b)(5), struck out (b) The President shall appoint the adjutant ‘‘, the Canal Zone,’’ after ‘‘each Territory’’ and ‘‘or the general of the District of Columbia and pre- Canal Zone’’ after ‘‘a Territory’’. scribe his grade and qualifications. Subsec. (d). Pub. L. 100–456, § 1234(b)(1), struck out (c) The President may detail as adjutant gen- ‘‘the Canal Zone,’’ after ‘‘Puerto Rico,’’. -

Annual Report of the Adjutant-General for the Year Ending

. Public Document No. 7 DOCS gij^ tommottttt^altlj of MaaHarljuB^ttfi '^ ' L L , ANNUAL REPORT ADJUTANT GENERAL Year ending December 31, 1928 Publication op this Document approved bt the Commission on Administration and Finance 600 3-'29 Order 4929 CONTENTS. PAGE Armories, List of 99 Register of the Massachusetts National Guard 101 Report of The Adjutant General 1 Report of the Armory Commission 7 Report of the Intelligence Section 10 Report of the Military Service Commission 8 Report of the State Inspector 10 Report of the State Judge Advocate 11 Report of the State Ordnance Officer 12 Report of Organization Commanders 32 Report of the State Quartermaster 19 Report of the State Surgeon 22 Report of the U. S. Property and Disbursing Officer 25 Retired Officers, Land Forces 60 Retired Officers, Naval Forces 95 ANNUAL REPORT. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts, The Adjutant General's Office, State House, Boston, December 31, 1928. To His Excellency the Governor mid Commander-in-Chief: In accordance with the provisions of Section 23 of Chapter 465 of the Acts of 1924, I hereby submit the Annual Report of the Massachusetts Volunteer Militia for the year ending December 31, 1928. Appended are the reports of the Chiefs of Departments, Staff Corps, Armory Commission, and organization commanders. Enrolled Militia. On December 31, 1928, the total enrolled militia of the Commonwealth was 731,288, a loss of 1,195 over 1927. National Guard. The organization of the Massachusetts National Guard remains the same as last year. The restrictions imposed by Congress and the Militia Bureau still remain and prevent any increase in numbers in the Guard. -

SB 16 Page 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22

1 AN ACT 2 RELATING TO MILITARY AFFAIRS; INCREASING THE RANK REQUIRED TO 3 BE APPOINTED ADJUTANT GENERAL; REMOVING THE POSITION OF VICE 4 DEPUTY ADJUTANT GENERAL; CHANGING WHO MAY CONVENE A 5 COURT-MARTIAL. 6 7 BE IT ENACTED BY THE LEGISLATURE OF THE STATE OF NEW MEXICO: 8 SECTION 1. Section 20-1-5 NMSA 1978 (being Laws 1987, 9 Chapter 318, Section 5) is amended to read: 10 "20-1-5. ADJUTANT GENERAL--APPOINTMENT AND DUTIES.--In 11 case of a vacancy, the governor shall appoint as the adjutant 12 general of New Mexico for a term of five years an officer who 13 for three years immediately preceding the appointment as the 14 adjutant general of New Mexico has been federally recognized 15 as an officer in the national guard of New Mexico and who 16 during service in the national guard of New Mexico has 17 received federal recognition in the rank of colonel or 18 higher. The adjutant general shall not be removed from 19 office during the term for which appointed, except for cause 20 to be determined by a court-martial or efficiency board 21 legally convened for that purpose in the manner prescribed by 22 the national guard regulations of the United States 23 department of defense. The adjutant general shall have the 24 military grade of major general and shall receive the same 25 pay and allowances as is prescribed by federal law and SB 16 Page 1 1 regulations for members of the active military in the grade 2 of major general, unless a different rate of pay and 3 allowances is specified in the annual appropriations bill. -

Adjutant General Powerpoint Presentation

House Legislative Oversight Committee Office of The Adjutant General Major General Robert E. Livingston, Jr. Agenda • Introductions • Agency Myths • Key Laws Affecting the Agency • Agency Mission, Vision, and Goals • Key Deliverables and Potential Harm • Organization • Key Dates in History • Agency Successes/Issues/Emerging Issues • Internal Audit Process • Strategic Finances • Carry Forwards • Recommended Laws Changes • Recommended Internal Changes • Summary/Conclusion 2 Introductions • Major General Robert E. Livingston, Jr • Milton Montgomery The Adjutant General of South Carolina Deputy Director, Youth ChalleNGe/Job • Major General R. Van McCarty ChalleNGe Deputy Adjutant General • Brigadier General (R) John Motley • Brigadier General Jeff A. Jones Director, STARBASE Swamp Fox Assistant Adjutant General - Ground • Steven Jeffcoat • Brigadier General Russell A. Rushe Director, SC Military Museum Assistant Adjutant General - Air • Colonel Ronald F. Taylor • Brigadier General Brad Owens Chief of Staff - Army Director of the Joint Staff • Colonel Michael Metzler • Command Sergeant Major Russell A Vickery Director of Staff - Air State Command Sergeant Major • Colonel Brigham Dobson • Chief Warrant Officer 5 Kent Puffenbarger Construction & Facility Management Officer State Command Chief Warrant Officer • Kenneth C. Braddock • Major General Thomas Mullikin Chief of Staff for State Operations Commander, SC State Guard • Frank L. Garrick • Kim Stenson Chief Financial Officer, State Operations Director, SC Emergency Management Division 3 Agency -

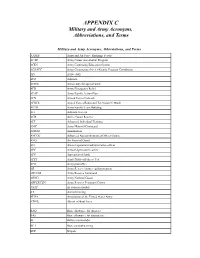

Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms

APPENDIX C Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms AAFES Army and Air Force Exchange Service ACAP Army Career and Alumni Program ACES Army Continuing Education System ACS/FPC Army Community Service/Family Program Coordinator AD Active duty ADJ Adjutant ADSW Active duty for special work AER Army Emergency Relief AFAP Army Family Action Plan AFN Armed Forces Network AFRTS Armed Forces Radio and Television Network AFTB Army Family Team Building AG Adjutant General AGR Active Guard Reserve AIT Advanced Individual Training AMC Army Materiel Command AMMO Ammunition ANCOC Advanced Noncommissioned Officer Course ANG Air National Guard AO Area of operations/administrative officer APC Armored personnel carrier APF Appropriated funds APFT Army Physical Fitness Test APO Army post office AR Army Reserve/Army regulation/armor ARCOM Army Reserve Command ARNG Army National Guard ARPERCEN Army Reserve Personnel Center ASAP As soon as possible AT Annual training AUSA Association of the United States Army AWOL Absent without leave BAQ Basic allowance for quarters BAS Basic allowance for subsistence BC Battery commander BCT Basic combat training BDE Brigade Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms cont’d BDU Battle dress uniform (jungle, desert, cold weather) BN Battalion BNCOC Basic Noncommissioned Officer Course CAR Chief of Army Reserve CASCOM Combined Arms Support Command CDR Commander CDS Child Development Services CG Commanding General CGSC Command and General Staff College -

The Americans from Thechemin Des Dames to the Marne

The first US troops in Soissons station, February 4, 1918. Fonds Valois - BdiC 1917-1918 AISNE The Americans from the Chemin des Dames to the Marne Grand Cerf crossroads, Villers-Cotterêts forest, July 19 1918. american supply base. America’s entry into Psychology and numbers Trucks unloading supplies. Fonds Valois - BdiC In the months preceding America’s entry into WW1, the prospec- tive involvement of American soldiers in the fighting on French soil greatly influenced the calculations of German and Allied strategists alike. Though it was inexperienced and faced organi- zational problems, the American Army numbered 200,000 men and its troops were fresh, unlike war-weary allied forces who had Mark MEIGS, in 1918. De guerre lasse, Dép.de been fighting for three years already and had experienced the l’Aisne, 2008. Translated from the French. horrors of trench warfare. American support was then crucial and likely to influence the outcome of the war. examine the various actions of the Ame- rican ships in the first months of 1917 rican Army, they do not deem them deci- that the USA could not avoid entering the sive, and hardly proportional to the num- war, there were a central Army Staff and ber of American soldiers on French soil national army officers able to implement at the end of the war, namely two million. such effort but there were inevitable blun- American actions did not decide the out- ders due to lack of coordination and to come of the war but the sheer presence the new conditions of organization and of their troops did, as all parties felt that recruitment. -

"With the Help of God and a Few Marines,"

WITH THE HELP OF GOD NDAFEW ff R E3 ENSE PETIT P LAC I DAM SUB LIBE > < m From the Library of c RALPH EMERSON FORBES 1866-1937 o n > ;;.SACHUSETTS BOSTON LIBRARY "WITH THE HELP OF GOD AND A FEW ]\/[ARINES" "WITH THE HELP OF GOD AND A FEW MARINES" BY BRIGADIER GENERAL A. W. CATLIN, U. S. M. C. WITH THE COLLABORATION OF WALTER A. DYER AUTHOR OF "HERROT, DOG OF BELGIUM," ETC ILLUSTRATED Gaeden City New York DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY 1919 » m Copyright, 1918, 1919, by DOUBLEDAY, PaGE & COMPANY All rights reserved, including that of translation into foreign languages including the Scandinavian UNIV. OF MASSACHUSETTS - LIBRARY { AT BOSTON CONTENTS PAGE ix Introduction , , . PART I ' MARINES TO THE FRONT I CHAPTER I. What Is A Marine? 3 II. To France! ^5 III. In the Trenches 29 IV. Over the Top 44 V. The Drive That Menaced Paris 61 PART II fighting to save PARIS VI. Going In 79 VIL Carrying On 9i VIII. "Give 'Em Hell, Boys!" 106 IX. In Belleau Wood and Bouresches 123 X. Pushing Through ^3^ XI. "They Fought Like Fiends'* ........ 161 XII. "Le Bois de LA Brigade de Marine" 171 XIII. At Soissons and After 183 PART III soldiers of the sea XIV. The Story of the Marine Corps 237 XV. Vera Cruz AND THE Outbreak of War 251 XVI. The Making of a Marine 267 XVII. Some Reflections on the War 293 APPENDIX I. Historical Sketch 3^9 II. The Marines' Hymn .323 III. Major Evans's Letter 324 IV. Cited for Valour in Action 34^ LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS HALF-TONE Belleau Wood . -

State of Connecticut Office of the Adjutant General National Guard Armory 360 Broad Street Hartford, Connecticut 06105-3795

STATE OF CONNECTICUT OFFICE OF THE ADJUTANT GENERAL NATIONAL GUARD ARMORY 360 BROAD STREET HARTFORD, CONNECTICUT 06105-3795 AND DEPARTMENT OF INTERIOR ON CONNECTICUT NATIONAL GUARD SUPPORT TO DRUG ENFORCEMENT OPERATIONS 1. PURPOSE For the purpose of this memorandum, Connecticut National Guard will be referred to as CTNG and Department of Interior will be referred to as DOI. The term Department of the Interior (DOI) encompasses all subordinate bureaus, services, and offices. The term bureau includes any major component of the Department of the Interior. This memorandum sets forth policies and procedures agreed to by the Adjutant General of the State of Connecticut and the DOI regarding: a. The gathering of information concerning drug trafficking in the State of Connecticut acquired by the CTNG as a result of their normal training missions, and the sharing of such information with the DOI. b. The use of CTNG personnel in support of drug enforcement operations. 2. OBJECTIVES Define missions/support agreed upon by CTNG and DOI. 3. AUTHORITY This Support agreement is entered into by the Connecticut National Guard pursuant to authority contained in National Guard Regulation 500-2 and Air National Guard Regulation 55-04. The Department of the Interior enters into this agreement under 43 U.S.C. Sec. 1733 authorizing the Secretary of the Interior to enforce...federal laws and regulations...relating to public lands and resources. 4. POLICIES AND PROCEDURES a. CTNG personnel will not be employed in a law enforcement role and will be acting under state active duty status or pursuant to Title 32 orders. No assistance of any kind will be rendered when, in the opinion of The Adjutant General, or his designated representative, the rendering of assistance will degrade the normal training mission of the CTNG. -

Dan Dailey Usmc

Dan dailey usmc Continue Dan Daly redirects here. For other features, see Dan Daly (disambiguating). Not to be confused with Daniel A. Dailey. Daniel DalyBirth nameDaniel JosephBorn(1873-11-11)November 11, 1873Glen Cove, New York, U.S.DiedApril 27, 1937(1937-04-27) (63 years Glendale, Queens, New York, New York, U. S.BuriedCypress Hills National CemeteryAllegiance United States of AmericaService/branch United States Marine CorpsYears of service1899–1929Rank Sergeant MajorUnit2nd Marine Regiment6th Marine RegimentBattles/warsBoxer Rebellion Battle of Peking Banana Wars Battle of Veracruz Battle of Fort Dipitie World War I Battle of Belleau Wood Battle of Bell-Saint-Mi-Mi.La Battle of Blanc Mont Ridge awardsMedal of Honor (2)Navy CrossDistinguished Service CrossCroix de guerreMédaille militaire Daniel Joseph Daly (November 11, 1873 – April 27, 1937) was a United States Marine and one of the nineteen men (including seven Marines) who received the Medal of Honor twice. All Navy double winners, except Daly and Division General Smedley Butler, received both Medals of Honor for the same action. Daly is said to have shouted: Come on, you sons of bitches, do you want to live forever? to the men of his company before accusing the Germans during the Battle of Belleau Wood in World War I. Daly was reportedly offered a commission of officer twice who replied that he would rather be an exceptional sergeant than just another officer. Awards[edit] Medals of Honor are on display at the National Marine Corps Museum in Triangle, Virginia. Biography Daly being awarded the Médaille militaire. Daniel Joseph Daly was born on November 11, 1873, in Glen Cove, New York.