SFU Library Thesis Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 24/04/2017 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 24/04/2017 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars All Of Me - John Legend Blue Ain't Your Color - Keith Urban Shape of You - Ed Sheeran Jackson - Johnny Cash 24K Magic - Bruno Mars EXPLICIT Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton Piano Man - Billy Joel Unchained Melody - The Righteous Brothers Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Don't Stop Believing - Journey Black Velvet - Alannah Myles Sweet Home Alabama - Lynyrd Skynyrd Girl Crush - Little Big Town Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks My Way - Frank Sinatra Santeria - Sublime Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Turn The Page - Bob Seger Killing Me Softly - The Fugees Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Love on the Brain - Rihanna EXPLICIT He Stopped Loving Her Today - George Jones Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Wannabe - Spice Girls Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Can't Stop The Feeling - Trolls Love Shack - The B-52's Summer Nights - Grease Closer - The Chainsmokers I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor Crazy - Patsy Cline Amarillo By Morning - George Strait A Whole New World - Aladdin Let It Go - Idina Menzel Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker At Last - Etta James How Far I'll Go - Moana These Boots Are Made For Walkin' - Nancy Sinatra Strawberry Wine - Deana Carter My Girl - The Temptations Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses Fly Me To The Moon -

Discography of the Mainstream Label

Discography of the Mainstream Label Mainstream was founded in 1964 by Bob Shad, and in its early history reissued material from Commodore Records and Time Records in addition to some new jazz material. The label released Big Brother & the Holding Company's first material in 1967, as well as The Amboy Dukes' first albums, whose guitarist, Ted Nugent, would become a successful solo artist in the 1970s. Shad died in 1985, and his daughter, Tamara Shad, licensed its back catalogue for reissues. In 1991 it was resurrected in order to reissue much of its holdings on compact disc, and in 1993, it was purchased by Sony subsidiary Legacy Records. 56000/6000 Series 56000 mono, S 6000 stereo - The Commodore Recordings 1939, 1944 - Billy Holiday [1964] Strange Fruit/She’s Funny That Way/Fine and Mellow/Embraceable You/I’ll Get By//Lover Come Back to Me/I Cover the Waterfront/Yesterdays/I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues/I’ll Be Seeing You 56001 mono, S 6001 stereo - Begin the Beguine - Eddie Heywood [1964] Begin the Beguine/Downtown Cafe Boogie/I Can't Believe That You're in Love with Me/Carry Me Back to Old Virginny/Uptown Cafe Boogie/Love Me Or Leave Me/Lover Man/Save Your Sorrow 56002 mono, S 6002 stereo - Influence of Five - Hawkins, Young & Others [1964] Smack/My Ideal/Indiana/These Foolish Things/Memories Of You/I Got Rhythm/Way Down Yonder In New Orleans/Stardust/Sittin' In/Just A Riff 56003 mono, S 6003 stereo - Dixieland-New Orleans - Teagarden, Davison & Others [1964] That’s A- Plenty/Panama/Ugly Chile/Riverboat Shuffle/Royal Garden Blues/Clarinet -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 20/12/2018 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 20/12/2018 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton Perfect - Ed Sheeran Grandma Got Run Over By A Reindeer - Elmo & All I Want For Christmas Is You - Mariah Carey Summer Nights - Grease Crazy - Patsy Cline Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Feliz Navidad - José Feliciano Have Yourself A Merry Little Christmas - Michael Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Killing me Softly - The Fugees Don't Stop Believing - Journey Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Zombie - The Cranberries Baby, It's Cold Outside - Dean Martin Dancing Queen - ABBA Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Rockin' Around The Christmas Tree - Brenda Lee Girl Crush - Little Big Town Livin' On A Prayer - Bon Jovi White Christmas - Bing Crosby Piano Man - Billy Joel Jackson - Johnny Cash Jingle Bell Rock - Bobby Helms Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Baby It's Cold Outside - Idina Menzel Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Let It Go - Idina Menzel I Wanna Dance With Somebody - Whitney Houston Last Christmas - Wham! Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow! - Dean Martin You're A Mean One, Mr. Grinch - Thurl Ravenscroft Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Africa - Toto Rudolph The Red-Nosed Reindeer - Alan Jackson Shallow - A Star is Born My Way - Frank Sinatra I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor The Christmas Song - Nat King Cole Wannabe - Spice Girls It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas - Dean Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Please Come Home For Christmas - The Eagles Wagon Wheel - -

![Society's Child [Verse 1] Come to My Door, Baby Face Is Clean And](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2689/societys-child-verse-1-come-to-my-door-baby-face-is-clean-and-292689.webp)

Society's Child [Verse 1] Come to My Door, Baby Face Is Clean And

Society’s Child (Janis Ian) [Verse 1] Preachers of equality Come to my door, baby Think they believe it, then why Face is clean and shining black won't they just let us be? as night My mother went to answer you [Chorus 2] know They say I can't see you That you looked so fine anymore baby Now I could understand your Can't see you anymore tears and your shame She called you "boy" instead of [Verse 3] your name One of these days I'm gonna When she wouldn't let you stop my listening inside Gonna raise my head up high When she turned and said One of these days I'm gonna "But honey, he's not our kind." raise my glistening wings and fly [Chorus 1] But that day will have to wait She says I can't see you any for a while more, baby Baby I'm only society's child Can't see you anymore When we're older things may change [Verse 2] But for now this is the way, they Walk me down to school, baby must remain Everybody's acting deaf and blind [Chorus 3] Until they turn and say, "Why I say I can't see you anymore don't you stick to your own baby kind." Can't see you anymore My teachers all laugh, their No, I won't see you anymore, smirking stares baby Cutting deep down in our affairs 193 "Society's Child", or "Baby I've Been Thinking", was a song written, composed, and recorded in 1965 by Janis Ian. -

June 26, 1995

Volume$3.00Mail Registration ($2.8061 No. plusNo. 1351 .20 GST)21-June 26, 1995 rn HO I. Y temptation Z2/Z4-8I026 BUM "temptation" IN ate, JUNE 27th FIRST SIN' "jersey girl" r"NAD1AN TOUR DATES June 24 (2 shows) - Discovery Theatre, Vancouver June 27 a 28 - St. Denis Theatre, Montreal June 30 - NAC Theatre, Ottawa July 4 - Massey Hall, Toronto PRODUCED BY CRAIG STREET RPM - Monday June 26, 1995 - 3 theUSArts ireartstrade of and andrepresentativean artsbroadcasting, andculture culture Mickey film, coalition coalition Kantorcable, representing magazine,has drawn getstobook listdander publishing companiesKantor up and hadthat soundindicated wouldover recording suffer thatKantor heunder wasindustries. USprepared trade spokespersonCanadiansanctions. KeithThe Conference for announcement theKelly, coalition, nationalof the was revealed Arts, expecteddirector actingthat ashortly. of recent as the a FrederickPublishersThe Society of Canadaof Composers, Harris (SOCAN) Authors and and The SOCANand Frederick Music project.the preview joint participation Canadian of SOCAN and works Harris in this contenthason"areGallup the theconcerned information Pollresponsibilityto choose indicated about from.highway preserving that to He ensure a and alsomajority that our pointedthere culturalthe of isgovernment Canadiansout Canadian identity that in MusiccompositionsofHarris three MusicConcert newCanadian Company at Hallcollections Toronto's on pianist presentedJune Royal 1.of Monica Canadian a Conservatory musical Gaylord preview piano of Chatman,introducedpresidentcomposers of StevenGuest by the and their SOCAN GellmanGaylord.speaker respective Foundation, and LouisThe composers,Alexina selections Applebaum, introduced Louie. Stephen were the originatethatisspite "an 64% of American the ofKelly abroad,cultural television alsodomination policies mostuncovered programs from in of place ourstatisticsscreened the media."in US; Canada indicatingin 93% Canada there of composersdesignedSeriesperformed (Explorations toThe the introduceinto previewpieces. -

N Ieman Reports

NIEMAN REPORTS Nieman Reports One Francis Avenue Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 Nieman Reports THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY VOL. 62 NO. 1 SPRING 2008 VOL. 62 NO. 1 SPRING 2008 21 ST CENTURY MUCKRAKERS THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION HARVARDAT UNIVERSITY 21st Century Muckrakers Who Are They? How Do They Do Their Work? Words & Reflections: Secrets, Sources and Silencing Watchdogs Journalism 2.0 End Note went to the Carnegie Endowment in New York but of the Oakland Tribune, and Maynard was throw- found times to return to Cambridge—like many, ing out questions fast and furiously about my civil I had “withdrawal symptoms” after my Harvard rights coverage. I realized my interview was lasting ‘to promote and elevate the year—and would meet with Tenney. She came to longer than most, and I wondered, “Is he trying to my wedding in Toronto in 1984, and we tried to knock me out of competition?” Then I happened to keep in touch regularly. Several of our class, Peggy glance over at Tenney and got the only smile from standards of journalism’ Simpson, Peggy Engel, Kat Harting, and Nancy the group—and a warm, welcoming one it was. I Day visited Tenney in her assisted living facility felt calmer. Finally, when the interview ended, I in Cambridge some years ago, during a Nieman am happy to say, Maynard leaped out of his chair reunion. She cared little about her own problems and hugged me. Agnes Wahl Nieman and was always interested in others. Curator Jim Tenney was a unique woman, and I thoroughly Thomson was the public and intellectual face of enjoyed her friendship. -

MUSIC LIST Email: Info@Partytimetow Nsville.Com.Au

Party Time Page: 1 of 73 Issue: 1 Date: Dec 2019 JUKEBOX Phone: 07 4728 5500 COMPLETE MUSIC LIST Email: info@partytimetow nsville.com.au 1 THING by Amerie {Karaoke} 100 PERCENT PURE LOVE by Crystal Waters 1000 STARS by Natalie Bassingthwaighte {Karaoke} 11 MINUTES by Yungblud - Halsey 1979 by Good Charlotte {Karaoke} 1999 by Prince {Karaoke} 19TH NERVIOUS BREAKDOWN by The Rolling Stones 2 4 6 8 MOTORWAY by The Tom Robinson Band 2 TIMES by Ann Lee 20 GOOD REASONS by Thirsty Merc {Karaoke} 21 - GUNS by Greenday {Karaoke} 21 QUESTIONS by 50 Cent 22 by Lilly Allen {Karaoke} 24K MAGIC by Bruno Mars 3 by Britney Spears {Karaoke} 3 WORDS by Cheryl Cole {Karaoke} 3AM by Matchbox 20 {Karaoke} 4 EVER by The Veronicas {Karaoke} 4 IN THE MORNING by Gwen Stefani {Karaoke} 4 MINUTES by Madonna And Justin 40 MILES OF ROAD by Duane Eddy 409 by The Beach Boys 48 CRASH by Suzi Quatro 5 6 7 8 by Steps {Karaoke} 500 MILES by The Proclaimers {Karaoke} 60 MILES AN HOURS by New Order 65 ROSES by Wolverines 7 DAYS by Craig David {Karaoke} 7 MINUTES by Dean Lewis {Karaoke} 7 RINGS by Ariana Grande {Karaoke} 7 THINGS by Miley Cyrus {Karaoke} 7 YEARS by Lukas Graham {Karaoke} 8 MILE by Eminem 867-5309 JENNY by Tommy Tutone {Karaoke} 99 LUFTBALLOONS by Nena 9PM ( TILL I COME ) by A T B A B C by Jackson 5 A B C BOOGIE by Bill Haley And The Comets A BEAT FOR YOU by Pseudo Echo A BETTER WOMAN by Beccy Cole A BIG HUNK O'LOVE by Elvis A BUSHMAN CAN'T SURVIVE by Tania Kernaghan A DAY IN THE LIFE by The Beatles A FOOL SUCH AS I by Elvis A GOOD MAN by Emerson Drive A HANDFUL -

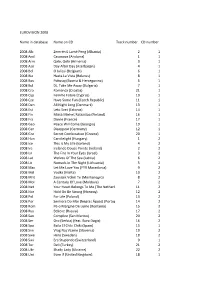

EUROVISION 2008 Name in Database Name on CD Track Number CD

EUROVISION 2008 Name in database Name on CD Track number CD number 2008 Alb Zemrën E Lamë Peng (Albania) 2 1 2008 And Casanova (Andorra) 1 1 2008 Arm Qele, Qele (Armenia) 3 1 2008 Aze Day After Day (Azerbaijan) 4 1 2008 Bel O Julissi (Belgium) 6 1 2008 Bie Hasta La Vista (Belarus) 8 1 2008 Bos Pokusaj (Bosnia & Herzegovina) 5 1 2008 Bul DJ, Take Me Away (Bulgaria) 7 1 2008 Cro Romanca (Croatia) 21 1 2008 Cyp Femme Fatale (Cyprus) 10 1 2008 Cze Have Some Fun (Czech Republic) 11 1 2008 Den All Night Long (Denmark) 13 1 2008 Est Leto Svet (Estonia) 14 1 2008 Fin Missä Miehet Ratsastaa (Finland) 16 1 2008 Fra Divine (France) 17 1 2008 Geo Peace Will Come (Georgia) 19 1 2008 Ger Disappear (Germany) 12 1 2008 Gre Secret Combination (Greece) 20 1 2008 Hun Candlelight (Hungary) 1 2 2008 Ice This Is My Life (Iceland) 4 2 2008 Ire Irelande Douze Pointe (Ireland) 2 2 2008 Isr The Fire In Your Eyes (Israel) 3 2 2008 Lat Wolves Of The Sea (Latvia) 6 2 2008 Lit Nomads In The Night (Lithuania) 5 2 2008 Mac Let Me Love You (FYR Macedonia) 9 2 2008 Mal Vodka (Malta) 10 2 2008 Mnt Zauvijek Volim Te (Montenegro) 8 2 2008 Mol A Century Of Love (Moldova) 7 2 2008 Net Your Heart Belongs To Me (The Netherlands) 11 2 2008 Nor Hold On Be Strong (Norway) 12 2 2008 Pol For Life (Poland) 13 2 2008 Por Senhora Do Mar (Negras Águas) (Portugal) 14 2 2008 Rom Pe-o Margine De Lume (Romania) 15 2 2008 Rus Believe (Russia) 17 2 2008 San Complice (San Marino) 20 2 2008 Ser Oro (Serbia) (feat. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

Youth Collection

TITLE AUTHOR LAST NAME AUTHOR FIRST NAME PUBLISHER AWARDS QUANTITY 1,2,3 A Finger Play Harcourt Brace & Company 2 1,2,3 in the Box Tarlow Ellen Scholastic 1,2,3 to the Zoo Carle Eric Philomel Books 10 Little Fingers and 10 Little Toes Fox & Oxenbury Mem & Helen HMH 38 Weeks Till Summer Vacation Kerby Mona Scholastic 50 Great Make-It, Take-It Projects Gilbert LaBritta Upstart Books A Band of Angels Hopkinson Deborah Houghton Mifflin Company A Band of Angels Mathis Sharon Houghton Mifflin Company A Beauty of a Plan Medearis Angela Houghton Mifflin Company A Birthday Basket for Tia Mora Pat Alladin Books A Book of Hugs Ross Dave Harper Collins Publishers A Boy Called Slow: The True Story of Sitting Bull Bruchac Joseph Philomel Books A Boy Named Charlie Brown Shulz Charles Metro Books A Chair for My Mother Williams Vera B. Mulberry Books A Corner of the Universe Freeman Don Puffin Books A Day With a Mechanic Winne Joanne Division of Grolier Publishing A Day With Air Traffic Controllers Winne Joanne Division of Grolier Publishing A Day with Wilbur Robinson Joyce William Scholastic A Flag For All Brimner Larry Dane Scholastic A Gathering of Days Mosel Arlene Troll Associates Caldecott A Gathering of Old Men Williams Karen Mullberry Paperback Books A Girl Name Helen Keller Lundell Margo Scholastic A Hero Ain't Nothin' but a Sandwich Bawden Nina Dell/Yearling Books A House Spider's Life Himmelman John Division of Grolier Publishing A Is For Africa Onyefulu Ifeoma Silver Burdett Ginn A Kitten is a Baby Cat Blevins Wiley Scholastic A Long Way From Home Wartski Maureen Signet A Million Fish … More or Less Byars Betsy Scholastic A Mouse Called Wolf King-Smith Dick Crown Publishers A Picture Book of Rosa Parks Keats Ezra Harper Trophy A Piggie Christmas Towle Wendy Scholastic Inc. -

With One Voice Community Choir Program

WITH ONE VOICE COMMUNITY CHOIR PROGRAM We hope being part of this choir program will bring you great joy, new connections, friendships, opportunities, new skills and an improved sense of wellbeing and even a job if you need one! You will also feel the creative satisfaction of performing at some wonderful festivals and events. If you have any friends, family or colleagues who would also like to get involved, please give them Creativity Australia’s details, which can be found on the inside of the front cover of this booklet. We hope the choir will grow to be a part of your life for many years. Also, do let us know of any performance or event opportunities for the choir so we can help them come to fruition. We would like to thank all our partners and supporters and ask that you will consider supporting the participation of others in your choir. Published by Creativity Australia. Please give us your email address and we will send you regular choir updates. Prepared by: Shaun Islip – With One Voice Conductor In the meantime, don’t forget to check out our website: www. Kym Dillon – With One Voice Conductor creativityaustralia.org.au Bridget a’Beckett – With One Voice Conductor Andrea Khoza – With One Voice Conductor Thank you for your participation and we are looking forward to a very Marianne Black – With One Voice Conductor exciting and rewarding creative journey together! Tania de Jong – Creativity Australia, Founder & Chair Ewan McEoin – Creativity Australia, General Manager Yours in song, Amy Scott – Creativity Australia, Program Coordinator -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.