A HISTORY of the TUARARANGAIA BLOCKS Wai894 #A3 Wai36 #A22 Wai 726 #A4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategic Direction Identification of Influences on the Whakatane District

IDENTIFICATION OF INFLUENCES ON THE WHAKATANE DISTRICT SECTION 1 - STRATEGIC DIRECTION IDENTIFICATION OF INFLUENCES ON THE WHAKATANE DISTRICT BACKGROUND on decisions made in a global environment, the Council additional compliance costs associated with meeting has a responsibility to ensure we retain the ongoing higher drinking water standards. Government policy will The Council’s plans and work programmes over the sustainability of our communities. Internet access impact on the Council, what it does, and the relative cost next ten years are targeted to meet the future needs enables increased visibility of the Whakatane District of the provision of services. These impacts need to be of the District. To do this successfully, it is important to to the rest of the world and to enable those who live managed. understand what will influence change in our district and here, access to increased knowledge, people in other In a country that is increasingly urbanised, the “one the elements of change that can be influenced by the countries, lifestyle choices and to goods and services. Council so that our communities can achieve their aims size fits all” approach does not necessarily benefit and aspirations for the future. NATIONAL IMPACTS our communities which make up some of the most socio-economically deprived areas of New Zealand. While the LTCCP 2009-2019 has a 10 year time horizon, A three-year electoral system leads to uncertainty around Our Council needs to be well placed and resourced many of the programmes and budgets have a longer the stability of policy decisions and the continuation to advocate for our communities and to ensure that it term focus. -

Combined Irrigation / Flood Control Storage in Upper Rangitāiki

Combined Irrigation and Flood Storage in Upper Rangitāiki Catchment Bay of Plenty Regional Council 13-Jan-2017 Doc No. 1 Combined Irrigation / Flood Control Storage in Upper Rangitāiki Initial Feasibility Study 13-Jan-2017 Prepared for – Bay of Plenty Regional Council – Co No.: N/A AECOM Combined Irrigation and Flood Storage in Upper Rangitāiki Catchment Combined Irrigation / Flood Control Storage in Upper Rangitāiki – Initial Feasibility Study Combined Irrigation / Flood Control Storage in Upper Rangitāiki Initial Feasibility Study Client: Bay of Plenty Regional Council Co No.: N/A Prepared by AECOM New Zealand Limited 121 Rostrevor Street, Hamilton 3204, PO Box 434, Waikato MC, Hamilton 3240, New Zealand T +64 7 834 8980 F +64 7 834 8981 www.aecom.com 13-Jan-2017 Job No.: 60493009 AECOM in Australia and New Zealand is certified to ISO9001, ISO14001 AS/NZS4801 and OHSAS18001. © AECOM New Zealand Limited (AECOM). All rights reserved. AECOM has prepared this document for the sole use of the Client and for a specific purpose, each as expressly stated in the document. No other party should rely on this document without the prior written consent of AECOM. AECOM undertakes no duty, nor accepts any responsibility, to any third party who may rely upon or use this document. This document has been prepared based on the Client’s description of its requirements and AECOM’s experience, having regard to assumptions that AECOM can reasonably be expected to make in accordance with sound professional principles. AECOM may also have relied upon information provided by the Client and other third parties to prepare this document, some of which may not have been verified. -

Part B: Community Property 12 MARCH 2018

ASSET MANAGEMENT PLAN Part B: Community Property 12 MARCH 2018 whakatane.govt.nz Community Property - Asset Management Plan Part B – Community Property 2018 Draft Asset Management Plan Part B – Community Property 2018-28 Part B provides the specific Asset Management information for Community Property, for the period 2018-2028. X[A1228573] 2018-2028 Asset management Plan Page 1 of 66 Community Property - Contents Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................. 2 Foreword ................................................................................................................................................. 7 1 Asset Management Plan – Part A ................................................................................................ 7 2 Asset Management Plan – Part B ................................................................................................ 7 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 8 1 The Assets This Plan Covers ........................................................................................................ 8 Business Overview .................................................................................................................................. 9 1 Why we do it .............................................................................................................................. -

Assessment of Flooding and Drainage Issues at Kopuriki

Bay of Plenty Regional Council Assessment of Flooding and Drainage Issues at Kopuriki Bay of Plenty Regional Council Assessment of Flooding and Drainage Issues at Kopuriki Prepared By Opus International Consultants Ltd Peter Askey Whakatane Office Principal Environmental Engineer Level 1, Opus House, 13 Louvain Street PO Box 800, Whakatane 3158 New Zealand Reviewed By Telephone: +64 7 308 0139 Jack McConchie Facsimile: +64 7 308 4757 Principal Hydrologist Date: 30rd November 2017 Reference: 2-34346.00 Status: Issue 2 © Opus International Consultants Ltd 2017 Assessment of Flooding and Drainage Issues at Kopuriki i Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................... 1 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Background ....................................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Key Issues .......................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Land ownership ................................................................................................................. 3 1.4 Resource Consents ............................................................................................................ 3 2 Lake Aniwaniwa and the Rangitaiki River .......................................................... 5 2.1 Lake Accretion Rates ........................................................................................................ -

6118 NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE No. 228

6118 NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE No. 228 2. The Whakatane District Council's proposed classification of The Road Classification (New Plymouth City) the roads as set out in the Schedule is approved. Notice No. 1, 1987 3. The Road Classification (Whakatane District) Notice No. 1, Pursuant to Regulation 3 (8) of the Heavy Motor Vehicle 1987, signed the 9th day of November 1987*, issued pursuant Regulations 197 4 and a delegation from the Secretary for to Regulation 3 of the Heavy Motor Vehicle Regulations 1974, Transport, I, Carne Maurice Clissold, Chief Traffic Engineer, which relates to the roads described in the Schedule, is give the following notice: revoked. Notice Schedule 1. This notice may be cited as the Road Classification (New Whakatane District Plymouth City) Notice No. 1, 1987. Roads Classified in Class One. 2. The New Plymouth City Council's proposed classification of the roads as set out in the Schedule is approved. All roads within the urban areas of Whakatane, Edgecumbe, Matata, Ohope, Taneatua, Te Teko and Waimana. Schedule Arawa Road. Roads Classified in Class One Awaiti South Road: from Hallet Road to Matata Road. All roads or parts of roads under the control of New Plymouth City. Awakeri Road: from Awakeri to Edgecumbe. Signed at Wellington this 9th day of December 1987. East Bank Road: from No. 2 State Highway (Pokeno to Wellington via Gisborne) to Edgecumbe. C. M. CLISSOLD, Chief Traffic Engineer. Foster Road: from White Pine Bush Road to Grace Road. (MOT. 28/8/New Plymouth City) lnl940 Galatea Road: from No. 30 State Highway (Te Kuiti to Whakatane via Atiamuri) to Whirinaki Road. -

Kawerau Geothermal System Management Plan

KAWERAU GEOTHERMAL SYSTEM MANAGEMENT PLAN February 2018 Prepared in Collaboration with Executive Summary The Kawerau Geothermal System is located to the north-east of Kawerau within the Bay of Plenty Region, and partially underlies the township of Kawerau. It has been substantially developed for industrial purposes pursuant to resource consents granted by the Bay of Plenty Regional Council (BOPRC) under the Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA). This includes geothermal energy being used for electricity generation, industrial processes (direct heat) and cultural purposes. Bay of Plenty Regional Council has functions under Section 30 of the RMA for the management of geothermal resources. The Bay of Plenty Regional Policy Statement (RPS) requires the preparation of a System Management Plan (SMP) for the Kawerau Geothermal System as a key part of the way in which BOPRC intends to manage the Kawerau Geothermal System. This SMP has been prepared in collaboration with the four consent holders authorised to take more than 1,000 tonnes per day of geothermal fluid from the Kawerau Geothermal System, being: Mercury NZ Limited, Ngāti Tūwharetoa Geothermal Assets Limited, Geothermal Developments Ltd, and Te Ahi O Māui Partnership. Engagement has also been undertaken with tangata whenua and interested and potentially affected parties, including industrial operators using the geothermal resource. The purpose of this SMP is to ensure that the Kawerau Geothermal System is managed in a sustainable manner in accordance with the requirements of the RMA and the relevant policy and planning documents prepared under the RMA. The content anticipated in an SMP is set out in Policy GR7B of the RPS and includes objectives for its overall management and strategies to achieve the objectives The SMP is a non-statutory document and will be periodically reviewed and updated to ensure that it remains relevant and fit for purpose. -

Rangitāiki River Forum

Rangitāiki River Forum NOTICE IS GIVEN that the next meeting of the Rangitāiki River Forum will be held in Council Chambers, Whakatāne District Council, Civic Centre, Commerce Street, Whakatāne on: Friday, 7 June 2019 commencing at 10.00 am. Maramena Vercoe Chairperson Rangitāiki River Forum Rangit āiki River Forum Terms of Reference Interpretation “Rangit āiki River” means the Rangit āiki River and its catchment, including the: • Rangit āiki River • Whirinaki River • Wheao River • Horomanga River The scope and delegation of this Forum covers the geographical area of the Rangit āiki River catchment as shown in the attached map. Purpose The purpose of the Forum is as set out in Ng āti Manawa Claims Settlement Act 2012 and the Ng āti Whare Claims Settlement Act 2012: The purpose of the Forum is the protection and enhancement of the environmental, cultural, and spiritual health and wellbeing of the Rangit āiki River and its resources for the benefit of present and future generations. Despite the composition of the Forum as described in section 108, the Forum is a joint committee of the Bay of Plenty Regional Council and the Whakat āne District Council within the meaning of clause 30(1)(b) of Schedule 7 of the Local Government Act 2002. Despite Schedule 7 of the Local Government Act 2002, the Forum— (a) is a permanent committee; and (b) must not be discharged unless all appointers agree to the Forum being discharged. The members of the Forum must act in a manner so as to achieve the purpose of the Forum. Functions The principle function of the Forum is to achieve its purpose. -

Aspects of the Chronology, Structure and Thermal History of the Kawerau Geothermal Field

Aspects of the Chronology, Structure and Thermal History of the Kawerau Geothermal Field By Sarah Dawn Milicich A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geology Victoria University of Wellington School of Geography, Environment and Earth Sciences Wellington, New Zealand 2013 ii „It is what it is‟ id est quod est J.L. Wooden (pers. comm. 2010) iii iv ABSTRACT The development and management of high-temperature geothermal resources for electrical power generation requires accurate knowledge of the local geological conditions, particularly where they impact on the hydrology of the resource. This study is an integrated programme of work designed to develop new perspectives on the geological and structural framework of the Kawerau geothermal resource as a sound basis for field management. Although the geological approaches and techniques utilised in this study have previously been used, their application to an integrated study of a geothermal system in New Zealand has not been previously undertaken. Correlating volcanic and sedimentary stratigraphy in geothermal areas in New Zealand can be challenging due to similarities in lithology and the destruction of distinctive chemical, mineralogical and textural characteristic by hydrothermal alteration. A means to overcoming these issues is to utilise dating to correlate the stratigraphy. Zircons are resistant to the effects of typical hydrothermal conditions and were dated using SIMS techniques (SHRIMP-RG) to retrieve U–Pb ages on zircons. These age data were then used to correlate units across the field, in part aided by correlations to material that had previously been dated from fresh rock by 40Ar/39Ar techniques, and used to redefine the stratigraphic framework for the area. -

Trustpower-Soe-Greg-Ryder.Pdf

IN THE MATTER of the Resource Management Act 1991 AND IN THE MATTER of Proposed Plan Change 9 to the Bay of Plenty Regional Natural Resources Plan AND submissions and further submissions by Trustpower Limited STATEMENT OF EVIDENCE OF GREGORY IAN RYDER Evidence of G. I. Ryder 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 My full name is Gregory Ian Ryder. 1.2 I hold BSc. (First Class Honours) (1984) and PhD. (1989) degrees in Zoology from the University of Otago. For both my honours dissertation and PhD. thesis I studied stream ecology with particular emphasis on sedimentation and benthic macroinvertebrates. 1.3 I am a member of the following professional societies: (a) New Zealand Freshwater Society; (b) Royal Society of New Zealand; (c) Society for Freshwater Science (North America). 1.4 I am a Director and Environmental Scientist at Ryder Environmental Limited (Ryder) and have worked as a consultant for approximately 25 years. I work largely in the field of surface water quality and aquatic ecology. I also fulfil the role of an independent commissioner and have sat on over 25 resource consent hearings. 1.5 I have undertaken or been associated with a large number of investigations that have assessed the effects of abstractions and discharges on surface water ecosystems, the effects of existing and proposed impoundments, and the effects of land use activities that produce point source and non-point source discharges. 1.6 My work covers the whole of New Zealand. Private industries, utility companies, local and regional councils and government departments engage me to provide advice on a wide range of issues affecting surface waters. -

Fisheries Assessment of Waterways Throughout the Rangitaiki WMA

Fisheries assessment of waterways throughout the Rangitaiki WMA Title Title part 2 Bay of Plenty Regional Council Environmental Publication 2016/12 5 Quay Street PO Box 364 Whakatāne 3158 NEW ZEALAND ISSN: 1175-9372 (Print) ISSN: 1179-9471 (Online) Fisheries assessment of waterways throughout the Rangitāiki WMA Environmental Publication 2016/12 ISSN: 1175-9372 (Print) ISSN: 1179-9471 (Online) December 2016 Bay of Plenty Regional Council 5 Quay Street PO Box 364 Whakatane 3158 NEW ZEALAND Prepared by Alastair Suren, Freshwater Ecologist Acknowledgements Thanks to Julian Sykes (NIWA Christchurch), Geoff Burton, Whetu Kingi, (Te Whare Whananga O Awanuiarangi), Paddy Deegan and Sam Fuchs, for assistance with the field work. Many of the streams visited were accessible only through private land, and could only be accessed with the help and cooperation of landowners throughout the area. Funding for this work came from Rob Donald, Manager of the Science Team, Bay of Plenty Regional Council. Environmental Publication 2016/12 – Fisheries assessment of waterways throughout the Rangitāiki WMA i Dedication This report is dedicated to Geoff Burton, who was tragically taken from us too soon whilst out running near Opotiki. Although Geoff had connections to Ngati Maniapoto (Ngati Ngutu) and was born in the Waikato, he moved with his wife and children back to Torere in the early 2000s to be closer to her whanau. Geoff had been a board member of Te Kura o Torere and was also a gazetted Ngaitai kaitiaki. He was completing studies at Te Whare Wānanga o Awanuiārangi where he was studying Te Ahu o Taiao. It was during this time that his supervisors recommended Geoff to assist with the fish survey work described in this report. -

Rangitāiki River Estuary National Objectives Framework (NOF)

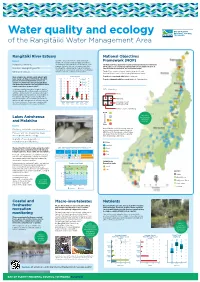

Water quality and ecology of the Rangitāiki Water Management Area Rangitāiki River Estuary National Objectives Issues: Nutrients can promote excess plant and algae growth. We measure plant and algae growth by Framework (NOF) Increasing nutrients measuring the concentrations of chlorophyll-a, the The National Policy Statement includes a National Objectives Framework pigment in plants that is used for photosynthesis. (NOF), which sets compulsory national values for freshwater to protect Nuisance biological growths The Rangitāiki estuary has the highest maximum ‘human health for recreation’ and ‘ecosystem health’. chlorophyll-a concentrations and the second highest Whitebait habitat median of the Bay of Plenty river estuaries. The NOF has a series of ‘bands’ ranging from A to D, and National Bottom Lines for the following attributes in rivers: River estuaries are dynamic environments with Chlorophyll-a To protect ecosystem health: Nitrate, Ammonia 16 large changes in tidal and river flows. About 63 Median To protect human health for recreation: E.coli, Cyanobacteria percent of native freshwater fish species use 14 estuaries to swim between fresh and salt water. 25%-75% 12 Like many river estuaries, the Rangitāiki has little Min-Max aquatic vegetation or macro-algae. 10 Freshwater usually dominates the water quality 8 NOF Banding of river estuaries. Flood flows and the delivery of 6 sediment and nutrients into estuaries can make it 4 Nitrate hard for plants and animals to live and grow there. Phosphorus and nitrogen are increasing in the 2 estuary. Nitrogen is also increasing in the whole 0 Ammonia catchment, while phosphorus is only increasing in -2 the lower catchment. -

Eastern Bay of Plenty Primary Schools Athletics Champs Results 2017

Eastern Bay of Plenty Primary Schools Athletics Champs Results 2017 9 Year Old Boys - 100m First Name Last Name School Place Eruera Kohunui Apanui School 1 Stowers Rico St Joseph's Whakatane 2 Kaio Moses James Street School 3 Ngawai Amoamo St Joseph's Catholic Scho 4 9 Year Old Boys - 200m First Name Last Name School Place Stowers Rico St Joseph's Whakatane 1 CJ Paikea Ashbrook School 2 Ryan Somerville Awakeri School 3 Kirk Dalton Allandale School 4 9 Year Old Boys - 60m First Name Last Name School Place Jacob Law St Joseph's Whakatane 1 Romeo Cross Edgecumbe School 2 Te Hau Paeroa Richmond Edgecumbe School 3 Ngawai Amoamo St Joseph's Catholic Scho 4 9 Year Old Boys - Discus First Name Last Name School Place Tawhio Fox-Kaipara Te Kura o Te Teko 1 Lytral Leach Kawerau Putauaki School 2 Christian Williams Opotiki Primary 3 Daimin Hudson Opotiki Primary 4 9 Year Old Boys - High Jump First Name Last Name School Place Kaio Moses James Street School 1 Zayka Ravenswood Kawerau South School 2 Tyler MacEy Apanui School 3 Kyan Edwards Awakeri School 4 9 Year Old Boys - Long Jump First Name Last Name School Place Romeo Cross Edgecumbe School 1 Ngawai Amoamo St Joseph's Catholic Scho 2 Rico Stowers St Joseph's Whakatane 3 Aydan Hall Otakiri School 4 9 Year Old Boys - Shot Put First Name Last Name School Place Hare Takarangi-Tawhai Kawerau Putauaki School 1 CJ Paikea Ashbrook School 2 Kingstyn Te Naiti Te Kura O Te Paroa 3 Zayka Ravenswood Kawerau South School 4 9 Year Old Boys - Vortex Eastern Bay of Plenty Primary Schools Athletics Champs Results