Journal 2005.Mp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The London Gazette of FRIDAY, 27Th MAY, 1955 Bp &Atf)Wft|> Registered As a Newspaper

40491 3141 SECOND SUPPLEMENT TO The London Gazette OF FRIDAY, 27th MAY, 1955 bp &atf)wft|> Registered as a Newspaper TUESDAY, 31 MAY, 1955 Air Ministry, 31 st May, 1955. Cadet Navigators. The QUEEN has been graciously pleased to 25th Mar. 1955. approve the award of the Military Medal to the 4161610 Bernard William Charles ASLETT under-mentioned warrant officer for gallantry (4161610) (period of service to count from 8th displayed in operations against hostile tribesmen:— Dec. 1954). 4161585 Colin Michael COOMBER (4161585) Company Sergeant Major Alawi ABDULLAH AUDHALI (period of service to count from 8th Dec. 1954). (3246), Aden Protectorate Levies. 2362669 George Stanley HALBERT (2362669) (period of service to count from 24th Nov. 1954). 4160897 Philip William MILES (4160897) (period of service to count from 24th Nov. 1954). Air Ministry, 3lst May, 1955. Transfer to a direct commission. As Flight Lieutenant (twelve years on the active ROYAL AIR FORCE. list and four years on the reserve). William Welch SPEAREY (130577). 12th Oct. Air Commodore D. A. WILSON, A.F.C., 1954 (period of service to count from 8th Feb. M.R.C.S., L.R.C.P., F.F.R., D.M.R.E., D.M.R., is 1951). appointed Honorary Surgeon to The QUEEN in succession to Air Vice-Marshal E. D. D. DICKSON, As Flying Officers (twelve years on the active list C.B., C.B.E., M.D., Ch.B., F.R.C.S.(Edin.), D.L.O., and four years on the reserve):— who vacates the appointment on retirement from Peter Dulvey STONHAM (3127345). -

THE ARABS of SURABAYA a Study of Sociocultural Integration a Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Master of Arts of the Australian

THE ARABS OF SURABAYA A Study of Sociocultural Integration * LIBRARY ^ A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts of the Australian National University by ABDUL RACHMAN PATJI June 1991 I declare that this thesis is my own composition, and that all sources have been acknowledged. Abdul Rachman PatJi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis has grown out of an academic effort that has been nourished by the support, advice, kindness, generosity, and patience of many people to whom I owe many debts. I am grateful to AIDAB (Australian International Development Assistance Bureau) for awarding me a scholarship which enabled me to pursue my study at the ANU (the Australian National University) in Canberra. To all the administrators of AIDAB, I express my gratitude. To LIPI (Indonesian Institute of Sciences), I would like to express my appreciation for allowing me to undertake study in Australia. My eternal thank go to Professor Anthony Forge for inviting me to study in the Department of Prehistory and Anthropology at ANU. I express my deepest gratitude and appreciation to Professor James Fox, my supervisor, for his scholarly assistance, encouragement, and supervision in the preparation of this thesis. He has always been an insightful commentator and a tireless editor of my work. I wish to thank all my teachers in the Department of Prehistory and Anthropology and all staff of the Department who always showed willingness to help during my study. The help rendered by Dr Doug Miles in commenting on Chapter I of this thesis and the attention given by Dr Margot Lyon during my study can never been forgotten. -

Identity in Hadhrami Society

Identity in Hadhrami Society Communities and Identities Shared elements of heritage contribute to the notion of a community as envisioned by its members, thereby shaping individual identities. In the words of Benedict Anderson, “all communities larger than primordial villages of face-to-face contact (and perhaps even these) are imagined.”1 Membership in an “imagined commu- nity,” or in a number of overlapping concentric communities, forms a meaningful background to an individual’s experience. At the same time, identity encompasses multiple levels and tiers, with different aspects predominating in different contexts. It is constantly sustained by comparisons, and the aspects relevant to comparison vary according to geographical and social settings.2 People from different parts of Hadhramawt shared an attachment to a land and a heritage, while they also identiµed with smaller units—territory, town, quar- ter, neighborhood—associated with speciµc local cultural attributes and histories. A further aspect of Hadhrami identity was membership in one of the social groups into which the larger society was divided; this membership was acquired at birth. Social group membership affected a person’s prospects in terms of marriage, edu- cation, occupation, and role in religious, economic, and political life. While dif- ferent social groups comprised different types of subgroups, all were composed of families, and membership in a family was another important aspect of individual identity. Another aspect of identity, gender, transected the others. Gender deter- mined important elements of a person’s role in family and society and affected an individual’s participation in education and in economic life; the boundaries of pos- sibility varied among the different social groups. -

ASPECTS of SOUTH YEMEN's FOREIGN POLICY L967-L982 by Fred Halliday Department of International History London School of Economic

ASPECTS OF SOUTH YEMEN'S FOREIGN POLICY L967-L982 by Fred Halliday Department of International History London School of Economics and Political Science University of London Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 1985 Thesis Abstract This study analyses the foreign relations of South Yemen (since 1970 the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen) from independence in 1967 until 1982. It covers the first four Presidencies of the post- independence period, with their attendant policy changes, and ends with the resolution of two of the more pressing foreign policy conflicts with which South Yemen was concerned, its support for the guerrillas in North Yemen, who were defeated in the spring of 1982, and its conflict with the Sultanate of Oman, with whom diplomatic relations were concluded in October 1982. Chapter One provides an outline of the background to South Yemen's foreign policy: the outcome of the independence movement itself and the resultant foreign policy orientations of the new government; the independence negotiations with Britain; and the manner in which, in the post-independence period, the ruling National Front sought to determine and develop its foreign policy. The remaining four chapters focus upon specific aspects of South Yemen's foreign policy that are, it is argued, of central importance. Chapter Two discusses relations with the West - with Britain, France, West Germany and the USA. It charts the pattern of continued economic ties with western European states, and the several political disputes which South Yemen had with them. Chapter Three discusses the issue of 'Yemeni Unity' - the reasons for the continued commitment to this goal, the policy of simultaneously supporting opposition in North Yemen and negotiating with the government there, and the course of policy on creating a unified Yemeni state. -

UNITED NATIONS Generkl ASSEMBLY

~ UNITED NATIONS GENERkL ASSEMBLY ENGLISH I I SPECIAL COMMIT'lj'E;E ON THE SITUATION WI'I'H REGARD TO TH_lj; IMPLEMENTAT I ON OF THE DECLARATI ON GN THE GRANTING OF INDEPENDENCE TO COLONIAL COUNTRIES AND PEOPLES DRAFT REPORT OF THE SPECIAL COMMI'ITEE ON THE SITUATION W 'IH REGARD TO 'I'HE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE DECLARATION ON THE GRANTING OF I NDEPENDENCE TO COLONIAL COUNTRIES AND PEOPLES* (covering its work during 1965) Rapporteur : Mr. K. NATWAR SI NGH (India) ADEN CONTENTS Paragr phs Page I. INFORMATION ON THE TERRITORY 1 - 8 2 A. General . 1 - 2 B. Political and Constitutional developments 3 - 0 3 C. EconJmic conditions 41 - 14 D. Soci 1 conditions 69 - 21 E. Educational conditions 85 - 23 II. CONSIDERJ}TI ON BY THE SPECIAL COMMITTEE 99 - 75 28 .. Introduction . 99 00 28 ✓ ,. A. Written petitions and hearings 101 - 20 28 B. Statements by members . 121 - 75 34 • III. ACTION T"4KEN BY THE SPECIAL COMMITTEE 276 - 02 78 ANNEX: REPORT OF TEE SUB - COMMITTEE ON ADEN * This docu1ent contains the draft chapter on Aden. Part I was previously issued as Annex III of the report of the Sub - Committee on Ade (A/AC.109/L.194 and Corr.1). Other chapters of the draft report of the Speci 1 Cammi ttee will ,. be reproduced as separate documents . / ... ' A/AC .109 /L .236 English Page 2 (!· .; I. INFORMATION ON THE TERRITORY A. GENERAL 1. The Territory of Aden consists of the Colony of Aden, no ...· known as Aden State and twenty Protectorates known as the Protectorate of South Arabia. -

Bibliography of the Arabian Peninsula

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF THE ARABIAN PENINSULA J.E. Peterson Prefatory Note: This bibliography concentrates on citations relating to the Arabian Peninsula that I have collected over some three decades. Items have been published in various Western languages as well as Arabic. This is very much a work in progress and cannot be considered complete. Similarly, presentation of the bibliography here in the present format should be regarded as an interim effort despite its imperfections. A number of older citations have yet to be transferred from notecards to the database on which this bibliography is based. Some items are unpublished, other citations are not complete (typically lacking volume details and page numbers for periodical citations). Shorter articles and those of a more transitory nature, i.e. newspaper and newsletter articles, have been excluded. I have not been able to examine all the items and therefore undoubtedly there are many mistakes in citations and inevitably some items have been included that do not actually exist. The bibliography is in simple and rough alphabetical order according to author only because I have had no opportunity to rearrange by subject. Alphabetization was done automatically within the original database and idiosyncrasies in the database regarding non-English diacritical marks may make alphabetization somewhat irregular. For similar reasons, the order in which entries by the same author are listed may also be irregular. The subjects reflect my own interests and therefore range from history through the social sciences and international affairs. Generally speaking, archaeology, the arts, the physical sciences, and many areas of culture, inter alia, have not been included. -

The Southern Reality Between Discord and Consensus

Study The Southern Reality Between Discord and Consensus A Vision in History, Politics and Society South Yemen 1960 – 2021 Farida Ahmed | August 2021 South 24 Center for News and Studies South24 Center for News and Studies The Southern Reality Between Discord and Consensus A Vision in History, Politics and Society South Yemen Farida Ahmed | August 2021 Center for News and Studies (All Rights Reserved for South24) (The opinions expressed in this study represent the author) 1 South24 Center for News and Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Topic 3 Summary 6 Introduction 7 General background 8 First: a historical glimpse about South 11 ● A union on the end road 13 Second: the political reality’s influence on South 15 ● Stages between discord and consensus 18 ● Components of the Post – 2015 war in Yemen 2015 19 Third: the southern society 20 ● Local identities and their diversity 23 ● The Southern tribal composition 25 ● Religious identity 26 Conclusion 28 Recommendations 30 References 2 South24 Center for News and Studies Summary Understanding the reality of South Yemen is currently of urgent importance. in spite of the discord and consensus aspects among the Southerners through different historical stages, and the great political influence caused by the interrelation, there are deeper ties and a state of national richness that has found their way in a society of variable cultural, social and economic characteristics as well as other fields. Such a thing requires maintenance and observance. it becomes clear that the coherent religious identity in South, based upon coexistence and harmony has not been affected by the sharp sectarian dimension during the latest Yemeni War, which turned by some Yemeni parties, such as the Islah party, ideologically affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood, and the Iranian-backed Houthis, to a religious and sectarian conflict. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses From Republics of Armies to Kata'ibs of Militia, Sheikhs, and Warlords: Civil-Military Relations in Iraq and Yemen CHIMENTE, ANTHONY,MICHAEL How to cite: CHIMENTE, ANTHONY,MICHAEL (2019) From Republics of Armies to Kata'ibs of Militia, Sheikhs, and Warlords: Civil-Military Relations in Iraq and Yemen , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/13331/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 From Republics of Armies to Kata'ibs of Militia, Sheikhs, and Warlords: Civil-Military Relations in Iraq and Yemen Abstract This thesis examines civil-military relations in two fragmented states of the Middle East, Iraq and Yemen. In the study of civil-military relations, scholars have historically viewed the ‘state’ as a given referent object of analysis when examining militaries in the region, the legacy of a predominantly Western- centric approach to understanding and explaining the centrality of the military to state identity. -

A Community of Muslims 1 1

Imperial Muslims 55528_Reese.indd528_Reese.indd i 005/10/175/10/17 112:162:16 PPMM To the People of Aden. May their suffering soon come to an end. 55528_Reese.indd528_Reese.indd iiii 005/10/175/10/17 112:162:16 PPMM Imperial Muslims Is lam, Community and Authority in the Indian Ocean, 1839–1937 S cott S. Reese 55528_Reese.indd528_Reese.indd iiiiii 005/10/175/10/17 112:162:16 PPMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © Scott S. Reese, 2018 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun—Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 10.5/12.5 Times New Roman by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7486 9765 6 (hardback) ISBN 978 0 7486 9766 3 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 3252 8 (epub) The right of Scott S. Reese to be identifi ed as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). 55528_Reese.indd528_Reese.indd iivv 005/10/175/10/17 112:162:16 PPMM Contents Acknowledgments vii Map 1 British Aden x Map 2 The Indian Ocean and its commercial routes xi Map 3 Yemen in the nineteenth century xii Introduction: A Community of Muslims 1 1. -

History of Islamic Empire in Urdu Pdf

History of islamic empire in urdu pdf Continue This article lists successive Muslim countries and dynasties from the rise of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad and early Muslim horses that began in 622 PO and continue to this day. The history of Muslim countries The early Muslim wars began in the life of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad. In addition to the work of southern Europe and the Indian sub-corner, his successors hit the great sheep of the Middle East and North Africa. In the decades after his death, the caliphate, founded by his oldest successors, known as the Rashidun Caliphate, inherits the Umayyad caliphate and later the Abbasid caliphate. While the caliphate gradually broke and fell, other Muslim dynasties rose; Some of these dynasties have been overgroced into Islamic empires, with some of the most notable being the Safavid dynasty, the Ottoman Empire and the Mughal Empire. Regional Empires Iran Shah Ismail I, Founder of Safavid Dynasty Qarinvand Dynasty (550-1110) Paduspanid (655-1598) Justanids (791-1004) Dulafid dynasty (800-898, Jibal) Samanid Empire (819-999) Tahirid Dynasty (821-873) Saffarid Dynasty (861-1003) Shirvanshah (861-1538) Alavid Dynasty (864-928) Sajid Dynasty (889-929) Ma'danids (890-1110, Makran) Aishanids (912-961) Husaynid Dynasty (914-929) Ziyarid Dynasty (928-43) Banu Ilyas (932-968) Buyid Dynasty (934-10) 62) Rawadid Dynasty (955-1071) , Tabriz) Hasanwayhid (959-1015) Annazidi (990-1180; Iran, Iraq) Ma'munid dynasty (995-1017) Kakuyid (1008-1141) Great Seljuq Empire (1029-1194) Nasrid dynasty (Sistan) (1029-1225) -

Da* Wain Islamic Thought: the Work Of'abd Allah Ibn 'Alawl Al-Haddad

Da* wa in Islamic Thought: the Work o f'Abd Allah ibn 'Alawl al-Haddad By Shadee Mohamed Elmasry University of London: School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of PhD. ProQuest Number: 10672980 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672980 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT Imam 'Abd Allah ibn 'Alawi al-Haddad was bom in 1044/1634, he was a scholar of the Ba 'Alawi sayyids , a long line of Hadrami scholars and gnostics. The Imam led a quiet life of teaching and, although blind, travelled most of Hadramawt to do daw a, and authored ten books, a diwan of poetry, and several prayers. He was considered the sage of his time until his death in Hadramawt in 1132/1721. Many chains of transmission of Islamic knowledge of East Africa and South East Asia include his name. Al-Haddad’s main work on da'wa, which is also the core of this study, is al-Da'wa al-Tdmma wal-Tadhkira al-'Amma (The Complete Call and the General Reminder ). -

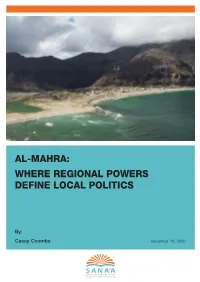

Al-Mahra: Where Regional Powers Define Local Politics

AL-MAHRA: WHERE REGIONAL POWERS DEFINE LOCAL POLITICS By: Casey Coombs December 16, 2020 AL-MAHRA: WHERE REGIONAL POWERS DEFINE LOCAL POLITICS By: Casey Coombs December 16, 2020 COVER PHOTO: Aerial view of Damqawt village in Hawf district of Al-Mahra, April 29, 2020. //Sana’a Center Editor’s Note: For security reasons, the Sana’a Center is withholding the name of a Yemeni co-author based in Al- Mahra whose research was crucial to this report. The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies is an independent think-tank that seeks to foster change through knowledge production with a focus on Yemen and the surrounding region. The Center’s publications and programs, offered in both Arabic and English, cover political, social, economic and security related developments, aiming to impact policy locally, regionally, and internationally. Oxford Research Group (ORG) is an independent organization that has been influential for nearly four decades in pioneering new, more strategic approaches to security and peacebuilding. Founded in 1982, ORG continues to pursue cutting-edge research and advocacy in the United Kingdom and abroad while managing innovative peacebuilding projects in several Middle Eastern countries. © COPYRIGHT SANA´A CENTER 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 4 Introduction 5 A New Governor and Broader Shifts in the South 7 An Immediate Test for Governor Yasser 9 Yasser Meets with Leaders of the Sit-In Committee Opposed to the Saudi Presence 10 Yasser Urges Political, Tribal Groups to Stand Against STC Moves in Socotra 12 Gulf Powers