A Community of Muslims 1 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Postprint (302.5Kb)

Robert W. Kvalvaag «Ya Habibi ya Muhammad»: Sami Yusuf og framveksten av en global muslimsk ungdomskultur Populærmusikk i islam er ikke et nytt fenomen, men i løpet av de siste 10 til 15 åra har denne musikkstilen nådd ut til millioner av unge muslimer, og bidratt til utviklingen av en egen global muslimsk ungdomskultur. Tekstene kan både være sekulære og religiøse, men i denne artikkelen fokuserer jeg på artister som fremfører tekster med eksplisitte religiøse budskap. Selv om islamsk popmusikk har likhetstrekk med vestlig popmusikk er disse to langt fra identiske størrelser, verken når det gjelder tekster eller musikalske uttrykksformer. Det pågår dessuten en debatt i islam om denne musikken er haram eller halal. I denne artikkelen presenteres noen av de viktigste artistene i sjangeren, med vekt på den teologien de formidler. Artikkelen fokuserer særlig på Muhammad-fromheten, slik denne uttrykkes og formidles i den islamske populærkulturen, og på denne fromhetens røtter i ulike islamske tradisjoner. Sami Yusuf Den viktigste artisten i islamsk popmusikk er Sami Yusuf. Sami Yusuf ble født i Iran i 1980, men familien kommer opprinnelig fra Aserbajdsjan. Da han var tre år flyttet familien Yusuf til London. Han utga sitt første album i 2003. Det ble en stor suksess og solgte i over 7 millioner eksemplarer. Etter at han utga sitt andre album i 2005 ble han i Time Magazine omtalt som «Islam’s Biggest Rock Star.» Etter dette har Yusuf kommet med enda tre utgivelser, og han har så langt solgt over 22 millioner album. Han er superstjerne for millioner av unge muslimer i mange land, ikke minst i Tyrkia, Malaysia og Indonesia. -

MENELUSURI TINGKAT PERCAYA DIRI GURU DALAM PEMBELAJARAN DI SMK NEGERI KOTA MANADO PROVINSI SULAWESI UTARA Abd

PROSIDING THE 2ND INTERNATIONAL SEMINAR ON CONTEMPORARY ISLAMIC ISSUES CONTEMPORARY ISSUES on Religion and Multiculturalism Swiss Bel Hotel Maleosan Manado, 9-10 Desember 2019 INSTITUT AGAMA ISLAM NEGERI (IAIN) MANADO 2019 PROSIDING THE 2ND INTERNATIONAL SEMINAR ON CONTEMPORARY ISLAMIC ISSUES Contemporary Issues On Religion And Multiculturalism Swiss Bel Hotel Maleosan Manado, 9-10 Desember 2019 Reviewer 1. Dr. Ardianto, M. Pd 2. Sulaiman Mappiasse, Ph. D 3. Dr. Hadirman,. Hum Editor : Dr. Edi Gunawan, M.HI & Rusdiyanto, M. Hum Tata Letak : Ahmad Bahaudin Desain Cover : Istana Agency Cetakan I, Desember 2019 ISBN: 978-602-53029-9-2 Diterbitkan Oleh: Fakultas Ushuluddin Adab dan Dakwah IAIN Manado Gedung Fakultas Ushuluddin Adab dan Dakwah IAN Manado Jl. Dr. S.H. Sarundajang Kawasan Ringroad I, Kota Manado Telp : +62431860616 E-Mail : [email protected] Web : www.fuad.iain-manado.ac.id Anggota Asosiasi Penerbit Perguruan Tinggi Indonesia (APPTI) Dicetak oleh: CV. ISTANA AGENCY Istana Publishing Jl. Nyi Adi Sari Gg. Dahlia I, Pilahan KG.I/722 RT 39/12 Rejowinangun-Kotagede-Yogyakarta 0851-0052-3476 [email protected] 0857-2902-2165 istanaagency istanaagency www.istanaagency.com Hak cipta dilindungi undang-undang Dilarang memperbanyak karya tulis ini dalam bentuk dan dengan cara apapun tanpa izin tertulis dari penerbit Proceeding The 2nd International Seminar on Contemporary Islamic Issues (ISCII) 2019 “Contemporary Issues on Religion and Multiculturalism” Swiss Bel Hotel Maleosan Manado, 9-10 Desember 2019 Stering Commitee Dr. Yusno A Otta, M. Ag Dr. Muhammad Imran, M. Th. I Dr. Sahari, M. Pd Advisor Delmus Puneri Salim, S.Ag., MA, M.Res., Ph.D (State Islamic Institute of Manado) Dr. -

Rituals of Islamic Spirituality: a Study of Majlis Dhikr Groups

Rituals of Islamic Spirituality A STUDY OF MAJLIS DHIKR GROUPS IN EAST JAVA Rituals of Islamic Spirituality A STUDY OF MAJLIS DHIKR GROUPS IN EAST JAVA Arif Zamhari THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E P R E S S E P R E S S Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/islamic_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Zamhari, Arif. Title: Rituals of Islamic spirituality: a study of Majlis Dhikr groups in East Java / Arif Zamhari. ISBN: 9781921666247 (pbk) 9781921666254 (pdf) Series: Islam in Southeast Asia. Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Islam--Rituals. Islam Doctrines. Islamic sects--Indonesia--Jawa Timur. Sufism--Indonesia--Jawa Timur. Dewey Number: 297.359598 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2010 ANU E Press Islam in Southeast Asia Series Theses at The Australian National University are assessed by external examiners and students are expected to take into account the advice of their examiners before they submit to the University Library the final versions of their theses. For this series, this final version of the thesis has been used as the basis for publication, taking into account other changesthat the author may have decided to undertake. -

Aden: Collapse of Ceasefire Anticipatory Briefing Note – 16 August 2019

YEMEN Aden: Collapse of ceasefire Anticipatory briefing note – 16 August 2019 MA Key risks and anticipated impact 4,500 civilians at risk of death or injury from urban conflict over a period of three months. Over 420,000 people would be trapped in their homes 1 million people at risk of disruptions to WASH and health services +50,000 northern traders, workers, and IDPs in need of international protection against execution, deportation and retaliatory violence Source: ACAPS (08/2019) Failure of peace talks leading to prolonged urban fighting in Aden could result in up to 4,500 civilian casualties over three months and cut access to services and markets for one million people. Reliability The international community needs to work with the Southern Transitional Council to protect traders, workers and IDPs of northern origin residing in Aden, who have been targeted by militias for deportation, This report is given a moderate level of confidence. Information is based on primary targeted killing and harassment. data and secondary data review, cross checked with operational actors in Yemen. However, the situation is fluid and could change rapidly. Risk forecasting is not an Attempts to resolve the conflict by force risk inflaming historic tribal tensions and cutting off vital fuel, aid exact science. and transport services to the rest of Yemen. Questions, comments? Contact us at: [email protected] ACAPS Anticipated Briefing Note: Collapse of ceasefire in Aden Purpose restore essential services and encourage the resumption of aid. However, renewed urban fighting in Aden would pose severe humanitarian risks for the civilian population. This report draws on current primary data, a secondary data review of previous conflicts, and discussions with operational actors in Yemen to provide a rapid estimate of the Conflict developments in Aden – August 2019 potential humanitarian impact of prolonged urban conflict in Aden to support early response planning (until agencies can conduct needs assessments). -

Asian Muslim Women in General

Introduction Huma Ahmed-Ghosh Muslim women’s lives in Asia traverse a terrain of experiences that defy the homogenization of “the Muslim woman.” The articles in this volume reveal the diverse lived experiences of Muslim women in Islamic states as well as in states with substantial Muslim populations in Asia and the North American diaspora.1 The contributions2 reflect upon the plurality of Mus- lim women’s experiences and realities and the complexity of their agency. Muslim women attain selfhood in individual and collective terms, at times through resistance and at other times through conformity. While women are found to resist multilevel patriarchies such as the State, the family, local feudal relations, and global institutions, they also accept some social norms and expectations about their place in society because of their beliefs and faith. Together, this results in women’s experience being shaped by particular structural constraints within different societies that frame their often limited options. One also has to be aware of academic rhetoric on “equality” or at least women’s rights in Islam and in the Quran and the reality of women’s lived experience. In bringing the diverse experiences of Asian women to light, I hope this book will be of social and political value to people who are increasingly curious, particularly post 9/11,3 about Islam and the lives of Muslim women globally. Authors in this collection locate their analysis in the intersectionality of numerous identities. While the focus in each contribution is on Muslim women, they are Muslim in a way framed by their specific context that includes class and ethnicity, and local positionality that is impacted by inter- national and national interests and by the specificities of their geographic locations. -

New Traffic Hub / Railway Station Near Bajpe Airport

Infrastructure Development Department Government of Karnataka Bangalore FEASIBILITY STUDY FOR PROVIDING RAILWAY STATION NEAR BAJPE AIRPORT AND A HUB FOR MULTI MODAL TRANSPORT SYSTEM MANGALORE FINAL REPORT JANUARY 2010 INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION (KARNATAKA) LIMITED Infra House, 39, 5th Cross, 8th Main, RMV Extn., Sadashiv Nagar, BANGALORE-560 080 In Association with Varna Engineering Consultants Pvt.Ltd #19/10, Mahalinga Chetty Street 3rd Floor, Mahalingapuram Chennai-600 034. TABLE OF CONTENTS KEY PLAN…………………………………………………………………………………….3 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 5 1.1. Background ........................................................................................................... 5 1.2. Industries & Trade ................................................................................................ 6 1.3. Tourist potential .................................................................................................... 8 1.4. Educational Centre ................................................................................................ 9 1.5. Location .............................................................................................................. 10 2. SCOPE OF WORK .............................................................................................................. 12 3. EXISTING FACILITIES .................................................................................................... -

The Central Islamic Lands

77 THEME The Central Islamic 4 Lands AS we enter the twenty-first century, there are over 1 billion Muslims living in all parts of the world. They are citizens of different nations, speak different languages, and dress differently. The processes by which they became Muslims were varied, and so were the circumstances in which they went their separate ways. Yet, the Islamic community has its roots in a more unified past which unfolded roughly 1,400 years ago in the Arabian peninsula. In this chapter we are going to read about the rise of Islam and its expansion over a vast territory extending from Egypt to Afghanistan, the core area of Islamic civilisation from 600 to 1200. In these centuries, Islamic society exhibited multiple political and cultural patterns. The term Islamic is used here not only in its purely religious sense but also for the overall society and culture historically associated with Islam. In this society not everything that was happening originated directly from religion, but it took place in a society where Muslims and their faith were recognised as socially dominant. Non-Muslims always formed an integral, if subordinate, part of this society as did Jews in Christendom. Our understanding of the history of the central Islamic lands between 600 and 1200 is based on chronicles or tawarikh (which narrate events in order of time) and semi-historical works, such as biographies (sira), records of the sayings and doings of the Prophet (hadith) and commentaries on the Quran (tafsir). The material from which these works were produced was a large collection of eyewitness reports (akhbar) transmitted over a period of time either orally or on paper. -

The Very Foundation, Inauguration and Expanse of Sufism: a Historical Study

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 6 No 5 S1 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy September 2015 The Very Foundation, Inauguration and Expanse of Sufism: A Historical Study Dr. Abdul Zahoor Khan Ph.D., Head, Department of History & Pakistan Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences, Faculty Block #I, First Floor, New Campus Sector#H-10, International Islamic University, Islamabad-Pakistan; Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Muhammad Tanveer Jamal Chishti Ph.D. Scholar-History, Department of History &Pakistan Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences, Faculty Block #I, First Floor New Campus, Sector#H-10, International Islamic University, Islamabad-Pakistan; Email: [email protected] Doi:10.5901/mjss.2015.v6n5s1p382 Abstract Sufism has been one of the key sources to disseminate the esoteric aspects of the message of Islam throughout the world. The Sufis of Islam claim to present the real and original picture of Islam especially emphasizing the purity of heart and inner-self. To realize this objective they resort to various practices including meditation, love with fellow beings and service for mankind. The present article tries to explore the origin of Sufism, its gradual evolution and culmination. It also seeks to shed light on the characteristics of the Sufis of the different periods or generations as well as their ideas and approaches. Moreover, it discusses the contributions of the different Sufi Shaykhs as well as Sufi orders or Silsilahs, Qadiriyya, Suhrwardiyya, Naqshbandiyya, Kubraviyya and particularly the Chishtiyya. Keywords: Sufism, Qadiriyya, Chishtiyya, Suhrwardiyya, Kubraviyya-Shattariyya, Naqshbandiyya, Tasawwuf. 1. Introduction Sufism or Tasawwuf is the soul of religion. -

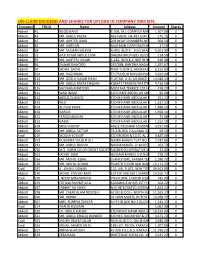

Un-Claim Dividend and Shares for Upload in Company Web Site

UN-CLAIM DIVIDEND AND SHARES FOR UPLOAD IN COMPANY WEB SITE. Company FOLIO Name Address Amount Shares Abbott 41 BILQIS BANO C-306, M.L.COMPLEX MIRZA KHALEEJ1,507.00 BEG ROAD,0 PARSI COLONY KARACHI Abbott 43 MR. ABDUL RAZAK RUFI VIEW, JM-497,FLAT NO-103175.75 JIGGAR MOORADABADI0 ROAD NEAR ALLAMA IQBAL LIBRARY KARACHI-74800 Abbott 47 MR. AKHTER JAMIL 203 INSAF CHAMBERS NEAR PICTURE600.50 HOUSE0 M.A.JINNAH ROAD KARACHI Abbott 62 MR. HAROON RAHEMAN CORPORATION 26 COCHINWALA27.50 0 MARKET KARACHI Abbott 68 MR. SALMAN SALEEM A-450, BLOCK - 3 GULSHAN-E-IQBAL6,503.00 KARACHI.0 Abbott 72 HAJI TAYUB ABDUL LATIF DHEDHI BROTHERS 20/21 GORDHANDAS714.50 MARKET0 KARACHI Abbott 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD616.00 KARACHI0 Abbott 96 ZAINAB DAWOOD 267/268, BANTWA NAGAR LIAQUATABAD1,397.67 KARACHI-190 267/268, BANTWA NAGAR LIAQUATABAD KARACHI-19 Abbott 97 MOHD. SADIQ FIRST FLOOR 2, MADINA MANZIL6,155.83 RAMTLA ROAD0 ARAMBAG KARACHI Abbott 104 MR. RIAZUDDIN 7/173 DELHI MUSLIM HOUSING4,262.00 SOCIETY SHAHEED-E-MILLAT0 OFF SIRAJUDULLAH ROAD KARACHI. Abbott 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE14,040.44 APARTMENT0 PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. Abbott 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND4,716.50 KARACHI-74000.0 Abbott 135 SAYVARA KHATOON MUSTAFA TERRECE 1ST FLOOR BEHIND778.27 TOOSO0 SNACK BAR BAHADURABAD KARACHI. Abbott 141 WASI IMAM C/O HANIF ABDULLAH MOTIWALA95.00 MUSTUFA0 TERRECE IST FLOOR BEHIND UBL BAHUDARABAD BRANCH BAHEDURABAD KARACHI Abbott 142 ABDUL QUDDOS C/O M HANIF ABDULLAH MOTIWALA252.22 MUSTUFA0 TERRECE 1ST FLOOR BEHIND UBL BAHEDURABAD BRANCH BAHDURABAD KARACHI. -

Restoration of Amiriya Madrasa Rada, Yemen

2Q6LWH5HYLHZ5HSRUW <(0 E\$\ú̧O7NHO<DYX] 5HVWRUDWLRQRI$PLUL\D0DGUDVD 5DGD<HPHQ &RQVHUYDWRU 6HOPDDO5DGL &OLHQW *HQHUDO2UJDQL]DWLRQRI$QWLTXLWLHV0XVHXPVDQG0DQXVFULSWV 'HVLJQ RQJRLQJ &RPSOHWHG RQJRLQJ Restoration of Amiriya Madrasa Rada, Yemen I. Introduction The Amiriya Madrasa was built by the last sultan of the Tahirid Dynasty at the beginning of the sixteenth century. It is quite a large madrasa, including several spaces that were probably private living spaces alongside a masjid and teaching rooms. The decoration, structure and form of the spaces are rich and varied. Extensive stucco decoration in qudad plaster and gypsum covers the walls and domes alongside tempera paintings. The dangerous condition of the madrasa first prompted interventions to deal with the structural elements of the building, such as the walls and roof. This was mostly finished by 1987. Cleaning and restoration of the stucco decoration continues to the present day, with a team of experts form Italy restoring the paintings. The whole project is financed by contributions from the Yemeni and Dutch governments. The project started in 1982 and completion is planned for the end of 2004. The masjid will then be opened for use by the inhabitants of Rada, and the rest of the building will become a museum under the Yemeni Government Organization for Antiquities, Museums and Manuscripts (GOAMM). II. Contextual Information A. Historical background Yemen’s earliest history, dating from the Stone and Bronze ages, has only recently been studied. For many years the region of Yemen was governed by a series of local rulers and the periods of their reigns overlap. Islam came to Yemen during the time of the Prophet. -

History: Class-6: Summary

www.gradeup.co HISTORY: CLASS-6: SUMMARY CHAPTER 9 - INDIA AND WORLD Points of Discussion • Contacts of India with South East Asia (Burma, Malaya, Cambodia, and Java) • Arabs in India INDIAN CONTACTS WITH THE OUTSIDE WORLD A. CONTACTS WITH SOUTH EAST ASIA • By the seventh century A.D., Indian's contact with south-east Asia had grown considerably. It had begun with the Indian merchants making voyages to these islands to sell their goods and to buy spices. These spices brought much wealth to the Indian merchants because they were sold to traders from western Asia. • Trade had increased and some merchants settled down in these countries. Gradually, some aspects of Indian culture were accepted by the people of south-east Asia. • The earliest contacts were with Burma (Suvarnabhumi), Malaya (Suvarnadvipa), Cambodia (Kamboja) and Java (Yavadvipa). Grand temples which were similar to Indian temples, such as the one at Angkor Vat in Cambodia, were built and many Hindu customs were practised. • The trade route between China and western Asia ran through central Asia. This was called the "Old Silk Route" because Chinese silk was one of the main articles of trade. Indian traders took part in this trade. • However, the culture of south-east Asian countries was not an imitation of Indian culture. In the villages, the old way of life continued. The aspects of Indian culture which were accepted were combined with their own old culture. • Grand temples were built in many of these countries. A new type of literature developed, which combined Indian influences with local traditions. • The art and architecture in these countries were influenced by both Hindu and Buddhist religions. -

How the Germans Brought Their Communism to Yemen

Miriam M. Müller A Spectre is Haunting Arabia Political Science | Volume 26 This book is dedicated to my parents and grandparents. I wouldn’t be who I am without you. Miriam M. Müller (Joint PhD) received her doctorate jointly from the Free Uni- versity of Berlin, Germany, and the University of Victoria, Canada, in Political Science and International Relations. Specialized in the politics of the Middle East, she focuses on religious and political ideologies, international security, international development and foreign policy. Her current research is occupied with the role of religion, violence and identity in the manifestations of the »Isla- mic State«. Miriam M. Müller A Spectre is Haunting Arabia How the Germans Brought Their Communism to Yemen My thanks go to my supervisors Prof. Dr. Klaus Schroeder, Prof. Dr. Oliver Schmidtke, Prof. Dr. Uwe Puschner, and Prof. Dr. Peter Massing, as well as to my colleagues and friends at the Forschungsverbund SED-Staat, the Center for Global Studies at the University of Victoria, and the Political Science Depart- ment there. This dissertation project has been generously supported by the German Natio- nal Academic Foundation and the Center for Global Studies, Victoria, Canada. A Dissertation Submitted in (Partial) Fulfillment of the Requirements for the- Joint Doctoral Degree (Cotutelle) in the Faculty of Political and Social Sciences ofthe Free University of Berlin, Germany and the Department of Political Scien- ceof the University of Victoria, Canada in October 2014. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommer- cial-NoDerivs 4.0 (BY-NC-ND) which means that the text may be used for non- commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author.