Halmstad University School of Business and Engineering Diversity of Vascular Plants in Swedish Forests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phylogenetics, Flow-Cytometry and Pollen Storage in Erica L

Institut für Nutzpflanzenwissenschaft und Res sourcenschutz Professur für Pflanzenzüchtung Prof. Dr. J. Léon Phylogenetics, flow-cytometry and pollen storage in Erica L. (Ericaceae). Implications for plant breeding and interspecific crosses. Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades Doktor der Agrarwissenschaften (Dr. agr.) der Landwirtschaftlichen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn von Ana Laura Mugrabi de Kuppler aus Buenos Aires Institut für Nutzpflanzenwissenschaft und Res sourcenschutz Professur für Pflanzenzüchtung Prof. Dr. J. Léon Referent: Prof. Dr. Jens Léon Korreferent: Prof. Dr. Jaime Fagúndez Korreferent: Prof. Dr. Dietmar Quandt Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 15.11.2013 Erscheinungsjahr: 2013 A mis flores Rolf y Florian Abstract Abstract With over 840 species Erica L. is one of the largest genera of the Ericaceae, comprising woody perennial plants that occur from Scandinavia to South Africa. According to previous studies, the northern species, present in Europe and the Mediterranean, form a paraphyletic, basal clade, and the southern species, present in South Africa, form a robust monophyletic group. In this work a molecular phylogenetic analysis from European and from Central and South African Erica species was performed using the chloroplast regions: trnL-trnL-trnF and 5´trnK-matK , as well as the nuclear DNA marker ITS, in order i) to state the monophyly of the northern and southern species, ii) to determine the phylogenetic relationships between the species and contrasting them with previous systematic research studies and iii) to compare the results provided from nuclear data and explore possible evolutionary patterns. All species were monophyletic except for the widely spread E. arborea , and E. manipuliflora . The paraphyly of the northern species was also confirmed, but three taxa from Central East Africa were polyphyletic, suggesting different episodes of colonization of this area. -

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

4010 Northern Atlantic Wet Heaths with Erica Tetralix

Technical Report 2008 08/24 MANAGEMENT of Natura 2000 habitats Northern Atlantic wet heaths with Erica tetralix 4010 Directive 92/43/EEC on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora The European Commission (DG ENV B2) commissioned the Management of Natura 2000 habitats. 4010 Northern Atlantic wet heaths with Erica tetralix This document was completed in March 2008 by Mark Hampton (NatureBureau, UK) on behalf of Ecosystems. Comments, data or general information were generously provided by: Mats Eriksson, MK Natur- och Miljökonsult, Sweden. Simon Barnett, Countryside Officer, West Berkshire Council, UK. Ola Bengtsson (ecological consultant), Pro Natura, Sweden Simon Caporn, Reader in Environmental Ecology, Department of Environmental & Geographical Sciences,Manchester Metropolitan University, UK. Geert De Blust, Research Institute for Nature and Forest, Research Group Nature and Forest Management, Belgium Simon Stainer, Natural England, UK Coordination: Concha Olmeda, ATECMA & Daniela Zaghi, Comunità Ambiente ©2008 European Communities ISBN 978-92-79-08323-5 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged Hampton M. 2008. Management of Natura 2000 habitats. 4010 Northern Atlantic wet heaths with Erica tetralix. European Commission This document, which has been prepared in the framework of a service contract (7030302/2006/453813/MAR/B2 "Natura 2000 preparatory actions: Management Models for Natura 2000 Sites”), is not legally binding. Contract realised by: ATECMA S.L. (Spain), COMUNITA AMBIENTE (Italy), -

Northern Ireland Information for H4010

European Community Directive on the Conservation of Natural Habitats and of Wild Fauna and Flora (92/43/EEC) Fourth Report by the United Kingdom under Article 17 on the implementation of the Directive from January 2013 to December 2018 Supporting documentation for the conservation status assessment for the habitat: H4010 ‐ Northern Atlantic wet heaths with Erica tetralix NORTHERN IRELAND IMPORTANT NOTE ‐ PLEASE READ • The information in this document is a country‐level contribution to the UK Reporton the conservation status of this habitat, submitted to the European Commission aspart of the 2019 UK Reporting under Article 17 of the EU Habitats Directive. • The 2019 Article 17 UK Approach document provides details on how this supporting information was used to produce the UK Report. • The UK Report on the conservation status of this habitat is provided in a separate doc‐ ument. • The reporting fields and options used are aligned to those set out in the European Com‐ mission guidance. • Explanatory notes (where provided) by the country are included at the end. These pro‐ vide an audit trail of relevant supporting information. • Some of the reporting fields have been left blank because either: (i) there was insuffi‐ cient information to complete the field; (ii) completion of the field was not obligatory; and/or (iii) the field was only relevant at UK‐level (sections 10 Future prospects and11 Conclusions). • For technical reasons, the country‐level future trends for Range, Area covered by habitat and Structure and functions are only available in a separate spreadsheet that contains all the country‐level supporting information. • The country‐level reporting information for all habitats and species is also available in spreadsheet format. -

European Glacial Relict Snails and Plants: Environmental Context of Their Modern Refugial Occurrence in Southern Siberia

bs_bs_banner European glacial relict snails and plants: environmental context of their modern refugial occurrence in southern Siberia MICHAL HORSAK, MILAN CHYTRY, PETRA HAJKOV A, MICHAL HAJEK, JIRI DANIHELKA, VERONIKA HORSAKOV A, NIKOLAI ERMAKOV, DMITRY A. GERMAN, MARTIN KOCI, PAVEL LUSTYK, JEFFREY C. NEKOLA, ZDENKA PREISLEROVA AND MILAN VALACHOVIC Horsak, M., Chytry, M., Hajkov a, P., Hajek, M., Danihelka, J., Horsakov a,V.,Ermakov,N.,German,D.A.,Ko cı, M., Lustyk, P., Nekola, J. C., Preislerova, Z. & Valachovic, M. 2015 (October): European glacial relict snails and plants: environmental context of their modern refugial occurrence in southern Siberia. Boreas, Vol. 44, pp. 638–657. 10.1111/bor.12133. ISSN 0300-9483. Knowledge of present-day communities and ecosystems resembling those reconstructed from the fossil record can help improve our understanding of historical distribution patterns and species composition of past communities. Here, we use a unique data set of 570 plots explored for vascular plant and 315 for land-snail assemblages located along a 650-km-long transect running across a steep climatic gradient in the Russian Altai Mountains and their foothills in southern Siberia. We analysed climatic and habitat requirements of modern populations for eight land-snail and 16 vascular plant species that are considered characteristic of the full-glacial environment of central Europe based on (i) fossil evidence from loess deposits (snails) or (ii) refugial patterns of their modern distribu- tions (plants). The analysis yielded consistent predictions of the full-glacial central European climate derived from both snail and plant populations. We found that the distribution of these 24 species was limited to the areas with mean annual temperature varying from À6.7 to 3.4 °C (median À2.5 °C) and with total annual precipitation vary- ing from 137 to 593 mm (median 283 mm). -

Carex of New England

Field Guide to Carex of New England Lisa A. Standley A Special Publication of the New England Botanical Club About the Author: Lisa A. Standley is an environmental consultant. She obtained a B.S, and M.S. from Cornell University and Ph.D. from the University of Washington. She has published several articles on the systematics of Carex, particularly Section Phacocystis, and was the author of several section treatments in the Flora of North America. Cover Illustrations: Pictured are Carex pensylvanica and Carex intumescens. Field Guide to Carex of New England Lisa A. Standley Special Publication of the New England Botanical Club Copyright © 2011 Lisa A. Standley Acknowledgements This book is dedicated to Robert Reed, who first urged me to write a user-friendly guide to Carex; to the memory of Melinda F. Denton, my mentor and inspiration; and to Tony Reznicek, for always sharing his expertise. I would like to thank all of the people who helped with this book in so many ways, particularly Karen Searcy and Robert Bertin for their careful editing; Paul Somers, Bruce Sorrie, Alice Schori, Pam Weatherbee, and others who helped search for sedges; Arthur Gilman, Melissa Dow Cullina, and Patricia Swain, who carefully read early drafts of the book; and to Emily Wood, Karen Searcy, and Ray Angelo, who provided access to the herbaria at Harvard University, the University of Massachusetts, and the New England Botanical Club. CONTENTS Introduction .......................................................................................................................1 -

Dwarf Shrub Heath (Uk Bap Broad Habitat)

DWARF SHRUB HEATH (UK BAP BROAD HABITAT) This broad habitat comprises vegetation in which dwarf shrubs are abundant or dominant. The dwarf shrubs here are most commonly ling Calluna vulgaris, bell heather Erica cinerea, cross-leaved heath E. tetralix, blaeberry Vaccinium myrtillus, cowberry V. vitis-idaea and crowberry Empetrum nigrum, but less commonly include bog bilberry V. uliginosum, bearberry Arctostaphylos uva-ursi, alpine bearberry A. alpinus, dwarf juniper Juniperus communis ssp. nana and western gorse Ulex gallii. The main division among these heaths in Scotland is between wet heaths and dry heaths. Wet heaths contain at least one of deergrass Scirpus cespitosus, purple moor-grass Molinia caerulea, Erica tetralix and bog myrtle Myrica gale in good quantity, or smaller quantities of these individual species attaining high cover collectively. Wet heath vegetation can resemble that of the Bog broad habitat, but differs in having little or no hare’s-tail cottongrass Eriophorum vaginatum, and the bog mosses Sphagnum papillosum and S. magellanicum. Wet heath vegetation on peat >50 cm deep is classed as bog. Dry heaths have little or no Scirpus, Molinia, Myrica or E. tetralix and are mostly dominated by Calluna or Vaccinium myrtillus. This broad habitat is widespread and common in Scotland, especially in the uplands where it dominates very large areas. Wet heath is most common in the western Highlands and Hebrides: in these areas it is the most extensive type of semi-natural vegetation. Further east dry heaths predominate. Dwarf shrub heaths can be of high conservation interest, especially for birds, mammals, insects, bryophytes and lichens. Many west Highland and Hebridean heaths are of international importance for their oceanic liverwort floras. -

The Inland-Heath Communities of the Netherlands

The Inland-Heath communities of the Netherlands J.T. de Smidt (Botanical Museum and Herbarium, Utrecht) (received July 15th, 1965) CONTENTS I. Introduction 143 II. The influenceoftheheatherbeetle (Lochmaea 146 suturalis) .... III. The communities 148 1. The dry heath complex (Calluna vulgaris)I 148 1.1. Calluna heaths 148 1.1.1. Calluna variant *148 1.1.2. Festuca variant 148 1.1.3. Festuca-Genista variant 148 1.2. Calluna-Empetrumheaths 148 1.2.1. Empetrum variant 149 1.2.2. Empetrum-Festuca variant 149 1.2.3. Empetrum-Festuca-Arnica variant 149 1.3. Calluna-Vaccinium heaths 150 1.3.1. Vaccinium variant 150 1.3.2. Vaccinium-Deschampsia variant 150 1.3.3. Vaccinium-Genista variant 151 1.4. Calluna-Sarothamnus heaths 151 1.4.1. Sarothamnus variant 152 1.4.2. Sarothamnus-Genista variant 152 1.5. Calluna-Erica cinerea heaths 153 1.6. Calluna-Carex ericetorum heaths 153 2. The humid heath complex (Calluna-Erica tetralix) 154 2.1. Calluna-Erica tetralix heaths 154 2.1.1. Calluna-Erica tetralix variant 154 2.1.2. Calluna-Erica tetralix-Festuca variant 155 2.1.3. Calluna-Erica tetralix-Festuca-Genista variant 155 2.1.4. Calluna-Erica tetralix-Festuca-Genista-Orchis maculata variant 156 2.2. Calluna-Erica tetralix-Empetrum heaths 156 2.2.1. Empetrum variant 156 2.2.2. Empetrum-Festuca variant 156 2.2.3. Empetrum-Festuca-Genista variant 156 2.3. Calluna-Erica tetralix-Vaccinium heaths 157 2.3.1. Vaccinium variant 157 2.3.2. Vaccinium-Festuca-Genistavariant 157 3. The wet heath complex (Erica tetralix) 158 3.1. -

Cyperaceae of Alberta

AN ILLUSTRATED KEY TO THE CYPERACEAE OF ALBERTA Compiled and writen by Linda Kershaw and Lorna Allen April 2019 © Linda J. Kershaw & Lorna Allen This key was compiled using information primarily from and the Flora North America Association (2008), Douglas et al. (1998), and Packer and Gould (2017). Taxonomy follows VASCAN (Brouillet, 2015). The main references are listed at the end of the key. Please try the key this summer and let us know if there are ways in which it can be improved. Over the winter, we hope to add illustrations for most of the entries. The 2015 S-ranks of rare species (S1; S1S2; S2; S2S3; SU, according to ACIMS, 2015) are noted in superscript ( S1; S2;SU) after the species names. For more details go to the ACIMS web site. Similarly, exotic species are followed by a superscript X, XX if noxious and XXX if prohibited noxious (X; XX; XXX) according to the Alberta Weed Control Act (2016). CYPERACEAE SedgeFamily Key to Genera 1b 01a Flowers either ♂ or ♀; ovaries/achenes enclosed in a sac-like or scale-like structure 1a (perigynium) .....................Carex 01b Flowers with both ♂ and ♀ parts (sometimes some either ♂ or ♀); ovaries/achenes not in a perigynium .........................02 02a Spikelets somewhat fattened, with keeled scales in 2 vertical rows, grouped in ± umbrella- shaped clusters; fower bristles (perianth) 2a absent ....................... Cyperus 02b Spikelets round to cylindrical, with scales 2b spirally attached, variously arranged; fower bristles usually present . 03 03a Achenes tipped with a rounded protuberance (enlarged style-base; tubercle) . 04 03b Achenes without a tubercle (achenes 3a 3b often beaked, but without an enlarged protuberence) .......................05 04a Spikelets single; stems leafess . -

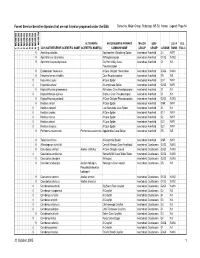

Sensitive Species That Are Not Listed Or Proposed Under the ESA Sorted By: Major Group, Subgroup, NS Sci

Forest Service Sensitive Species that are not listed or proposed under the ESA Sorted by: Major Group, Subgroup, NS Sci. Name; Legend: Page 94 REGION 10 REGION 1 REGION 2 REGION 3 REGION 4 REGION 5 REGION 6 REGION 8 REGION 9 ALTERNATE NATURESERVE PRIMARY MAJOR SUB- U.S. N U.S. 2005 NATURESERVE SCIENTIFIC NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME(S) COMMON NAME GROUP GROUP G RANK RANK ESA C 9 Anahita punctulata Southeastern Wandering Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G4 NNR 9 Apochthonius indianensis A Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1G2 N1N2 9 Apochthonius paucispinosus Dry Fork Valley Cave Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 Pseudoscorpion 9 Erebomaster flavescens A Cave Obligate Harvestman Invertebrate Arachnid G3G4 N3N4 9 Hesperochernes mirabilis Cave Psuedoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G5 N5 8 Hypochilus coylei A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G3? NNR 8 Hypochilus sheari A Lampshade Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2G3 NNR 9 Kleptochthonius griseomanus An Indiana Cave Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 8 Kleptochthonius orpheus Orpheus Cave Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 9 Kleptochthonius packardi A Cave Obligate Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G2G3 N2N3 9 Nesticus carteri A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid GNR NNR 8 Nesticus cooperi Lost Nantahala Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 8 Nesticus crosbyi A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G1? NNR 8 Nesticus mimus A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2 NNR 8 Nesticus sheari A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2? NNR 8 Nesticus silvanus A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2? NNR -

SPECIES IDENTIFICATION GUIDE National Plant Monitoring Scheme SPECIES IDENTIFICATION GUIDE

National Plant Monitoring Scheme SPECIES IDENTIFICATION GUIDE National Plant Monitoring Scheme SPECIES IDENTIFICATION GUIDE Contents White / Cream ................................ 2 Grasses ...................................... 130 Yellow ..........................................33 Rushes ....................................... 138 Red .............................................63 Sedges ....................................... 140 Pink ............................................66 Shrubs / Trees .............................. 148 Blue / Purple .................................83 Wood-rushes ................................ 154 Green / Brown ............................. 106 Indexes Aquatics ..................................... 118 Common name ............................. 155 Clubmosses ................................. 124 Scientific name ............................. 160 Ferns / Horsetails .......................... 125 Appendix .................................... 165 Key Traffic light system WF symbol R A G Species with the symbol G are For those recording at the generally easier to identify; Wildflower Level only. species with the symbol A may be harder to identify and additional information is provided, particularly on illustrations, to support you. Those with the symbol R may be confused with other species. In this instance distinguishing features are provided. Introduction This guide has been produced to help you identify the plants we would like you to record for the National Plant Monitoring Scheme. There is an index at -

Waterton Lakes National Park • Common Name(Order Family Genus Species)

Waterton Lakes National Park Flora • Common Name(Order Family Genus species) Monocotyledons • Arrow-grass, Marsh (Najadales Juncaginaceae Triglochin palustris) • Arrow-grass, Seaside (Najadales Juncaginaceae Triglochin maritima) • Arrowhead, Northern (Alismatales Alismataceae Sagittaria cuneata) • Asphodel, Sticky False (Liliales Liliaceae Triantha glutinosa) • Barley, Foxtail (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Hordeum jubatum) • Bear-grass (Liliales Liliaceae Xerophyllum tenax) • Bentgrass, Alpine (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Podagrostis humilis) • Bentgrass, Creeping (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Agrostis stolonifera) • Bentgrass, Green (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Calamagrostis stricta) • Bentgrass, Spike (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Agrostis exarata) • Bluegrass, Alpine (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Poa alpina) • Bluegrass, Annual (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Poa annua) • Bluegrass, Arctic (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Poa arctica) • Bluegrass, Plains (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Poa arida) • Bluegrass, Bulbous (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Poa bulbosa) • Bluegrass, Canada (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Poa compressa) • Bluegrass, Cusick's (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Poa cusickii) • Bluegrass, Fendler's (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Poa fendleriana) • Bluegrass, Glaucous (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Poa glauca) • Bluegrass, Inland (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Poa interior) • Bluegrass, Fowl (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Poa palustris) • Bluegrass, Patterson's (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Poa pattersonii) • Bluegrass, Kentucky (Poales Poaceae/Gramineae Poa pratensis) • Bluegrass, Sandberg's (Poales