Hkmets Bulletin, Volume 9, Numbers 1/2, 1999

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Satoyama Initiative Thematic Review Vol. 4

Satoyama Initiative Thematic Review vol. 4 Sustainable Use of Biodiversity in Socio-ecological Production Landscapes and Seascapes (SEPLS) and its Contribution to Effective Area-based Conservation Satoyama Initiative Thematic Review vol. 4 Sustainable Use of Biodiversity in Socio-ecological Production Landscapes and Seascapes (SEPLS) and its Contribution to Effective Area-based Conservation Satoyama Initiative Thematic Review vol. 4 i Citation UNU-IAS and IGES (eds.) 2018, Sustainable Use of Biodiversity in Socio-ecological Production Landscapes and Seascapes and its Contribution to Effective Area-based Conservation (Satoyama Initiative Thematic Review vol. 4), United Nations University Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability, Tokyo. © United Nations University ISBN (Print): 978-92-808-4643-0 ISBN (E-version): 978-92-808-4592-1 Editors Suneetha M. Subramanian Evonne Yiu Beria Leimona Editorial support Yohsuke Amano Ikuko Matsumoto Federico Lopez-Casero Michaelis Yasuo Takahashi Rajarshi Dasgupta Kana Yoshino William Dunbar Raffaela Kozar English proofreading Susan Yoshimura Design/Printing Xpress Print Pte Ltd Cover photo credits (From top to bottom): SGP/COMDEKS Indonesia, Fausto O. Sarmiento, Mayra Vera, Sebastian Orjuela-Salazar Satoyama Initiative The Satoyama Initiative is a global effort, first proposed jointly by the United Nations University and the Ministry of the Environment of Japan (MOEJ), to realize ”societies in harmony with nature” and contribute to biodiversity conservation through the revitalization and sustainable management of ”socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes” (SEPLS). The United Nations University Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability (UNU-IAS) serves as the Secretariat of the International Partnership for the Satoyama Initiative (IPSI). The activities of the IPSI Secretariat are made possible through the financial contribution of the Ministry of the Environment, Japan. -

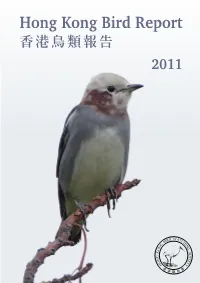

Hong Kong Bird Report 2011

Hong Kong Bird Report 2011 Hong Kong Bird Report 香港鳥類報告 2011 香港鳥類報告 Birdview report 2009-2010_MINOX.indd 1 5/7/12 1:46 PM Birdview report 2009-2010_MINOX.indd 1 5/7/12 1:46 PM 防雨水設計 8x42 EXWP I / 10x42 EXWP I • 8倍放大率 / 10倍放大率 • 防水設計, 尤合戶外及水上活動使用 • 密封式內充氮氣, 有效令鏡片防霞防霧 • 高折射指數稜鏡及多層鍍膜鏡片, 確保影像清晰明亮 • 能阻隔紫外線, 保護視力 港澳區代理:大通拓展有限公司 荃灣沙咀道381-389號榮亞工業大廈一樓C座 電話:(852) 2730 5663 傳真:(852) 2735 7593 電郵:[email protected] 野 外 觀 鳥 活 動 必 備 手 冊 www.wanlibk.com 萬里機構wanlibk.com www.hkbws.org.hk 觀鳥.indd 1 13年3月12日 下午2:10 Published in Mar 2013 2013年3月出版 The Hong Kong Bird Watching Society 香港觀鳥會 7C, V Ga Building, 532 Castle Peak Road , Lai Chi Kok, Kowloon , Hong Kong, China 中國香港九龍荔枝角青山道532號偉基大廈7樓C室 (Approved Charitable Institution of Public Character) (認可公共性質慈善機構) Editors: John Allcock, Geoff Carey, Gary Chow and Geoff Welch 編輯:柯祖毅, 賈知行, 周家禮, Geoff Welch 版權所有,不准翻印 All rights reserved. Copyright © HKBWS Printed on 100% recycled paper with soy ink. 全書採用100%再造紙及大豆油墨印刷 Front Cover 封面: Chestnut-cheeked Starling Agropsar philippensis 栗頰椋鳥 Po Toi Island, 5th October 2011 蒲台島 2011年10月5日 Allen Chan 陳志雄 Hong Kong Bird Report 2011: Committees The Hong Kong Bird Watching Society 香港觀鳥會 Committees and Officers 2013 榮譽會長 Honorary President 林超英先生 Mr. Lam Chiu Ying 執行委員會 Executive Committee 主席 Chairman 劉偉民先生 Mr. Lau Wai Man, Apache 副主席 Vice-chairman 吳祖南博士 Dr. Ng Cho Nam 副主席 Vice-chairman 吳 敏先生 Mr. Michael Kilburn 義務秘書 Hon. Secretary 陳慶麟先生 Mr. Chan Hing Lun, Alan 義務司庫 Hon. Treasurer 周智良小姐 Ms. Chow Chee Leung, Ada 委員 Committee members 李慧珠小姐 Ms. Lee Wai Chu, Ronley 柯祖毅先生 Mr. -

What Causes the Extremely Heavy Rainfall in Taiwan During Typhoon Morakot (2009)?

ATMOSPHERIC SCIENCE LETTERS Atmos. Sci. Let. 11: 46–50 (2010) Published online 1 February 2010 in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com) DOI: 10.1002/asl.255 What causes the extremely heavy rainfall in Taiwan during Typhoon Morakot (2009)? Xuyang Ge,1*TimLi,1 Shengjun Zhang,1,2 and Melinda Peng3 1International Pacific Research Center, SOEST, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI, USA 2State Key Laboratory of Severe Weather, Chinese Academy of Meteorological Sciences, Beijing, China 3Marine Meteorology Division, Naval Research Laboratory, Monterey, CA, USA *Correspondence to: Abstract Dr Xuyang Ge, University of Hawaii, 1680 East-West Road, Despite its category-2 intensity only, Typhoon (tropical cyclone in the Western Pacific) POST Building 401, Honolulu, Morakot produced a record-breaking rainfall in Taiwan. A cloud-resolving model is used to Hawaii 96822, USA. simulate this extreme rainfall event and understand the dynamic aspect under this event. E-mail: [email protected] Due to the interaction between Morakot and a monsoon system, a peripheral gale force monsoon surge appears to the south of Taiwan. The monsoon surge remains even in a sensitivity experiment in which Taiwan terrain is reduced. However, the rainfall amount in Taiwan is greatly reduced without high topography over Taiwan, suggesting the important role the local topography plays in producing heavy rainfall. The overall numerical results Received: 22 September 2009 indicate that it is the interaction among the typhoon, monsoon system, and local terrain that Revised: 29 November 2009 led to this extreme event. Copyright 2010 Royal Meteorological Society Accepted: 2 December 2009 Keywords: heavy rainfall; typhoon 1. Introduction may have a great impact on TC genesis and subse- quent motion. -

Chun-Chieh Wu (吳俊傑) Department of Atmospheric Sciences, National Taiwan University No. 1, Sec. 4, Roosevelt Rd., Taipei 1

Chun-Chieh Wu (吳俊傑) Department of Atmospheric Sciences, National Taiwan University No. 1, Sec. 4, Roosevelt Rd., Taipei 106, Taiwan Telephone & Facsimile: (886) 2-2363-2303 Email: [email protected], WWW: http://typhoon.as.ntu.edu.tw Date of Birth: 30 July, 1964 Education: Graduate: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Ph.D., Department of Earth Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences, May 1993 Thesis under the supervision of Professor Kerry A. Emanuel on "Understanding hurricane movement using potential vorticity: A numerical model and an observational study." Undergraduate: National Taiwan University, B.S., Department of Atmospheric Sciences, June 1986 Recent Positions: Professor and Chairman Department of Atmospheric Sciences, National Taiwan University August 2008 to present Director NTU Typhoon Research Center January 2009 to present Adjunct Research Scientist Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University July 2004 - present Professor Department of Atmospheric Sciences, National Taiwan University August 2000 to 2008 Visiting Fellow Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory, Princeton University January – July, 2004 (on sabbatical leave from NTU) Associate Professor Department of Atmospheric Sciences, National Taiwan University August 1994 to July 2000 Visiting Research Scientist Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory, Princeton University August 1993 – November 1994; July to September 1995 1 Awards: Gold Bookmarker Prize Wu Ta-You Popular Science Book Prize in Translation Wu Ta-You Foundation, 2008 Outstanding Teaching Award, National Taiwan University, 2008 Outstanding Research Award, National Science Council, 2007 Research Achievement Award, National Taiwan Univ., 2004 University Teaching Award, National Taiwan University, 2003, 2006, 2007 Academia Sinica Research Award for Junior Researchers, 2001 Memberships: Member of the American Meteorological Society. Member of the American Geophysical Union. -

Buchholz of Liability

Armed robbery at Lower Base DOLi clears O'Roarty, By Zaldy Dandan Variety News Staff TWO MEN sleeping in a car parked at the Lower Base beach side area were robbed and as Buchholz of liability saulted early Sunday moming by four uniden.tified baseball bat wielding men, according to De By Ferdie de la Torre Zachares said investigation 0 'Roarty on several occasions partment of Public Safety spokes Variety News Staff showed that the housemaid did without an approved contract from person Rose T. Ada. THE DEPARTMENT of Labor have the authority to seek an em DOLL Ada said the victims Nelson P. and Immigration has cleared gov ployer. "It's a relatively minor viola Javier, 43, and Rolando D. ernment lawyers Ross Buchholz However, Zachares explained, tion with a fine (at a maximum of Pestano, 33, lost $200 in cash, a andWilliamO'Roartyfromcrimi it appears that the housemaid was $500) involved. I am happy that diver's watch and a gold wedding nal liability in connection with working for Buchholz and Continued on page 23 ring to the robbers. DOLI's investigation of them for "They were sleeping in the car illegally hiring an alien worker waiting fortheirfriends, who were for domestic helper. PSS to impose hiring freeze fishing, when four men came to DOU Secretary Mark D. By Louie C. Alonso their car and woke them up," Ada Zachares yesterday said that based Variety News Staff said, citing the victims' account. on the department's findings there DUE TO· the limited budget it received for fiscal year 1999, the Public School System has now implemented a freeze-hiring policy in The men asked Javier and will beno criminal case to be filed Pestano for cigarettes and money, against Buchholz and O'Roarty. -

Tropical Cyclones in 1999

一九九九 熱 帶 氣 旋 TROPICAL CYCLONES IN 1999 二零零零年四月出版 Published April 2000 香港天文台編製 香港九龍彌敦道134A Prepared by: Hong Kong Observatory 134A Nathan Road Kowloon, Hong Kong © 版權所有。未經香港天文台台長同意,不得翻印本刊物任何部分內容。 © Copyright reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the permission of the Director of the Hong Kong Observatory. 本刊物可於下列地點購買: This publication is available from: (1)香港金鐘道66號 (1)Government Publications Centre 金鐘政府合署 Low Block, Ground Floor 低座地下 Queensway Government Offices 政府刊物銷售處 66 Queensway, Hong Kong (2)九龍尖沙咀彌敦道132號 (2)Hong Kong Observatory Resource Centre 美麗華大廈23樓2304-2309室 Rooms 2304-2309, 23/F, Miramar Tower 香港天文台資源中心 132 Nathan Road, Tsim Sha Tsui, Kowloon 本刊物的唯讀光碟隨書附送,歡迎就本 A CD-ROM version of this publication is 光碟提出意見。二零零零年以後,只有 attached. Suggestions on the CD-ROM are 唯讀光碟可提供參閱。此電子刊物亦將 invited. Only CD-ROM version is available in 會放入於香港天文台的網址。 year 2000. This electronic publication will also be posted on Internet at the Hong Kong 網址為:- Observatory web-site. 或 http://www.weather.gov.hk/ Homepage address: - http://www.info.gov.hk/hko/ http://www.weather.gov.hk/ or http://www.info.gov.hk/hko/ 本刊物的編製和發表,目的是促進資料交流。香港特別行政區 This publication is prepared and disseminated in the interest of 政府( 包括其僱員及代理人) 對於本刊物所載資料的準確性、完 promoting the exchange of information. The Government of the Hong 整性或效用,概不作出明確或暗示的保證、聲明或陳述;在法 Kong Special Administrative Region (including its servants and agents) makes no warranty, statement or representation, express or 律許可的範圍內,對於提供或使用這些資料而可能直接或間接 implied, with respect to the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of 引致任何損失、損壞或傷害( 包括死亡) ,亦不負任何法律承擔 the information contained herein, and in so far as permitted by law, 或責任( 包括疏忽責任) 。 shall not have any legal liability or responsibility (including liability for negligence) for any loss, damage, or injury (including death) which may result, whether directly or indirectly, from the supply or use of such information. -

Structural and Intensity Changes of Concentric Eyewall Typhoons in the Western North Pacific Basin

2632 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW VOLUME 141 Structural and Intensity Changes of Concentric Eyewall Typhoons in the Western North Pacific Basin YI-TING YANG AND HUNG-CHI KUO Department of Atmospheric Sciences, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan ERIC A. HENDRICKS AND MELINDA S. PENG Naval Research Laboratory, Monterey, California (Manuscript received 31 August 2012, in final form 7 February 2013) ABSTRACT An objective method is developed to identify concentric eyewalls (CEs) for typhoons using passive mi- crowave satellite imagery from 1997 to 2011 in the western North Pacific basin. Three CE types are identified: a CE with an eyewall replacement cycle (ERC; 37 cases), a CE with no replacement cycle (NRC; 17 cases), and a CE that is maintained for an extended period (CEM; 16 cases). The inner eyewall (outer eyewall) of the ERC (NRC) type dissipates within 20 h after CE formation. The CEM type has its CE structure maintained for more than 20 h (mean duration time is 31 h). Structural and intensity changes of CE typhoons are dem- onstrated using a T–Vmax diagram (where T is the brightness temperature and Vmax is the best-track es- timated intensity) for a time sequence of the intensity and convective activity (CA) relationship. While the intensity of typhoons in the ERC and CEM cases weakens after CE formation, the CA is maintained or increases. In contrast, the CA weakens in the NRC cases. The NRC (CEM) cases typically have fast (slow) northward translational speeds and encounter large (small) vertical shear and low (high) sea surface tem- 2 peratures. The CEM cases have a relatively high intensity (63 m s 1), and the moat size (61 km) and outer eyewall width (70 km) are approximately 50% larger than the other two categories. -

Arianas %Riety;~ · Micronesia's Leading Newspaper Since 1972 '&1 ~ Zachares: More Raids Coming up "Absolutely, Absolutely

' .UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII LIBRARi: arianas %riety;~ · Micronesia's Leading Newspaper Since 1972 '&1 ~ Zachares: More raids coming up "Absolutely, absolutely. There will probably be one very soon," •· Zachares said in an interview last Thursday. The "unannounced inspections" will be done on garment facto ries, construction firms, karaoke bars and nonresident workers' 1iv ing quarters, among others. These, officials said, are known ''hotspots" where numerous vio lations have been noted by inves tigators, including those on wages and the workers' occupational Mark Zachares safety. The Department of Labor and By Jojo Dass Immigration started conducting Variety News Staff "unannounced inspections" at the GOVERNMENT is poise to con height of the federal government's duct more raids this week on vari pressure on the CNMI early this Members of the First CNMI Youth Congress Luis Cepeda (right, foreground), Angel Demapan (center) and ous establishments and suspected year. Roman Palacios take their oaths during inauguration ceremonies in Capitol Hill Saturday. A total of 21 Youth lairs of overstaying nonresident Since then, close to 20 different Senators were sworn in. Photo by Tony Celis workers, Labor and Immigration establishments, including at least Secretary Mark Zachares told the nine garment factories, have been Variety. Continued on page 23 ---------- -------------·--1 Feds look into allegations of I Gov't holds up $4M maltreatment at DOLi centerJ Checks f Or Vendors By Jojo Dass of human rights violations are I Variety News Staff not within his office's jurisdic- By Haidee V. Eugenio tion projects, and suppliers of THE FEDERAL government is tion. Variety News Staff hospital and education m·aterials. -

The Frequency of Cyclonic Wind Storms Shapes Tropical Forest Dynamism and Functional Trait Dispersion

Article The Frequency of Cyclonic Wind Storms Shapes Tropical Forest Dynamism and Functional Trait Dispersion J. Aaron Hogan 1,*, Jess K. Zimmerman 2, Jill Thompson 3, María Uriarte 4, Nathan G. Swenson 5, Richard Condit 6,7, Stephen Hubbell 8, Daniel J. Johnson 9, I Fang Sun 10, Chia-Hao Chang-Yang 10, Sheng-Hsin Su 11 ID , Perry Ong 12 ID , Lillian Rodriguez 12, Carla C. Monoy 13, Sandra Yap 14 and Stuart J. Davies 15 1 Department of Biological Sciences, International Center for Tropical Botany, Florida International University, Miami, FL 33175, USA 2 Department of Environmental Science, University of Puerto Rico-Río Piedras, San Juan, PR 00936, USA; [email protected] 3 Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, Penicuik, Midlothian EH26 0QB, UK; [email protected] 4 Department of Ecology, Evolution & Environmental Biology, Columbia University, New York, NY 10027, USA; [email protected] 5 Department of Biology, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742, USA; [email protected] 6 Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, IL 60605, USA; [email protected] 7 Morton Arboretum, Lisle, IL 60532, USA 8 Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA; [email protected] 9 Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, NM 87545, USA; [email protected] 10 Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Studies, National Dong Hwa University, Hualien 97401, Taiwan; [email protected] (I.F.S.); [email protected] (C.-H.C.-Y.) 11 Taiwan Forestry Research Institute, Taipei 10066, Taiwan; [email protected] -

Field Measurements of Wind Effects on the Tallest Building in Hong Kong†

______________________________________________________________________http://www.paper.edu.cn THE STRUCTURAL DESIGN OF TALL AND SPECIAL BUILDINGS Struct. Design Tall Spec. Build. 12, 67–82 (2003) Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI:10.1002/tal.213 FIELD MEASUREMENTS OF WIND EFFECTS ON THE TALLEST BUILDING IN HONG KONG† Q. S. LI1*, Y. Q. XIAO1,2, C. K. WONG1 AND A. P. JEARY3 1Department of Building and Construction, City University of Hong Kong, Kowloon, Hong Kong 2School of Civil Engineering, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, China 3School of Building and Construction Science, University of Western Sydney, NSW, Australia SUMMARY Central Plaza has a height of approximately 374 m and is 78-storeys tall. It is the tallest structure in Hong Kong and was the highest reinforced-concrete building in the world when it was built several years ago. This paper describes some results obtained from the full-scale measurements of wind effects on Central Plaza. The field data such as wind speed, wind direction and acceleration responses have been measured during the close passage of several typhoons in recent years. Detailed analysis of the field data is conducted to investigate wind effects on the tall building. The full-scale measurements are compared with the wind tunnel results. The amplitude-dependent characteristics of damping that were obtained by using the random decrement technique are investigated on the basis of the field measurements. Copyright 2003 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 1. INTRODUCTION Hong Kong is close to the most active typhoon-generating area in the world, with tropical cyclones formed in the western Pacific Ocean or in the South China Sea several times each year. -

The Impact of Dropwindsonde on Typhoon Track Forecasts in DOTSTAR and T-PARC

1 Eyewall Evolution of Typhoons Crossing the Philippines and Taiwan: An 2 Observational Study 3 Kun-Hsuan Chou1, Chun-Chieh Wu2, Yuqing Wang3, and Cheng-Hsiang Chih4 4 1Department of Atmospheric Sciences, Chinese Culture University, Taipei, Taiwan 5 2Department of Atmospheric Sciences, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan 6 3International Pacific Research Center, and Department of Meteorology, University of 7 Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, Hawaii 8 4Graduate Institute of Earth Science/Atmospheric Science, Chinese Culture University, 9 Taipei, Taiwan 10 11 12 13 14 Terrestrial, Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences 15 (For Special Issue on “Typhoon Morakot (2009): Observation, Modeling, and 16 Forecasting Applications”) 17 (Accepted on 10 May, 2011) 18 19 ___________________ 20 Corresponding Author’s address: Kun-Hsuan Chou, Department of Atmospheric Sciences, 21 National Taiwan University, 55, Hwa-Kang Road, Yang-Ming-Shan, Taipei 111, Taiwan. 22 ([email protected]) 1 23 Abstract 24 This study examines the statistical characteristics of the eyewall evolution induced by 25 the landfall process and terrain interaction over Luzon Island of the Philippines and Taiwan. 26 The interesting eyewall evolution processes include the eyewall expansion during landfall, 27 followed by contraction in some cases after re-emergence in the warm ocean. The best 28 track data, advanced satellite microwave imagers, high spatial and temporal 29 ground-observed radar images and rain gauges are utilized to study this unique eyewall 30 evolution process. The large-scale environmental conditions are also examined to 31 investigate the differences between the contracted and non-contracted outer eyewall cases 32 for tropical cyclones that reentered the ocean. -

Significant Data on Major Disasters Worldwide, 1900-Present

DISASTER HISTORY Signi ficant Data on Major Disasters Worldwide, 1900 - Present Prepared for the Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance Agency for International Developnent Washington, D.C. 20523 Labat-Anderson Incorporated Arlington, Virginia 22201 Under Contract AID/PDC-0000-C-00-8153 INTRODUCTION The OFDA Disaster History provides information on major disasters uhich have occurred around the world since 1900. Informtion is mare complete on events since 1964 - the year the Office of Fore8jn Disaster Assistance was created - and includes details on all disasters to nhich the Office responded with assistance. No records are kept on disasters uhich occurred within the United States and its territories.* All OFDA 'declared' disasters are included - i.e., all those in uhich the Chief of the U.S. Diplmtic Mission in an affected country determined that a disaster exfsted uhich warranted U.S. govermnt response. OFDA is charged with responsibility for coordinating all USG foreign disaster relief. Significant anon-declared' disasters are also included in the History based on the following criteria: o Earthquake and volcano disasters are included if tbe mmber of people killed is at least six, or the total nmber uilled and injured is 25 or more, or at least 1,000 people art affect&, or damage is $1 million or more. o mather disasters except draught (flood, storm, cyclone, typhoon, landslide, heat wave, cold wave, etc.) are included if the drof people killed and injured totals at least 50, or 1,000 or mre are homeless or affected, or damage Is at least S1 mi 1l ion. o Drought disasters are included if the nunber affected is substantial.