The Jingshan Report: Opening China's Financial Sector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manchu Grammar (Gorelova).Pdf

HdO.Gorelova.7.vw.L 25-04-2002 15:50 Pagina 1 MANCHU GRAMMAR HdO.Gorelova.7.vw.L 25-04-2002 15:50 Pagina 2 HANDBOOK OF ORIENTAL STUDIES HANDBUCH DER ORIENTALISTIK SECTION EIGHT CENTRAL ASIA edited by LILIYA M. GORELOVA VOLUME SEVEN MANCHU GRAMMAR HdO.Gorelova.7.vw.L 25-04-2002 15:50 Pagina 3 MANCHU GRAMMAR EDITED BY LILIYA M. GORELOVA BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON • KÖLN 2002 HdO.Gorelova.7.vw.L 25-04-2002 15:50 Pagina 4 This book is printed on acid-free paper Die Deutsche Bibliothek – CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Gorelova, Liliya M.: Manchu Grammar / ed. by Liliya M. Gorelova. – Leiden ; Boston ; Köln : Brill, 2002 (Handbook of oriental studies : Sect.. 8, Central Asia ; 7) ISBN 90–04–12307–5 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gorelova, Liliya M. Manchu grammar / Liliya M. Gorelova p. cm. — (Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section eight. Central Asia ; vol.7) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 9004123075 (alk. paper) 1. Manchu language—Grammar. I. Gorelova, Liliya M. II. Handbuch der Orientalis tik. Achte Abteilung, Handbook of Uralic studies ; vol.7 PL473 .M36 2002 494’.1—dc21 2001022205 ISSN 0169-8524 ISBN 90 04 12307 5 © Copyright 2002 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by E.J. Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910 Danvers MA 01923, USA. -

December 2019 and March 2020 Graduation Program

GRADUATION PROGRAM DECEMBER 2019 AND MARCH 2020 CONFERRING OF DEGREES TABLE OF CONTENTS AND GRANTING Our Value Proposition to our Students OF DIPLOMAS and the Community 1 AND CERTIFICATES A Message from the Chancellor 2 A Message from the Vice-Chancellor and President 3 December 2019 100 years of opportunity and success 4 Flemington Racecourse, Grandstand At VU, family is everything 5 Epsom Road, Flemington VIC University Senior Executives 6 Acknowledgement of Country 7 March 2020 The University Mace – An Established Tradition 7 Victoria University, Footscray Park Academic Dress 8 Welcome to the Alumni Community 9 Social Media 10 Graduates 11 #vualumni #vicunigrads College of Arts and Education 12 vu.edu.au Victoria University Business School 14 College of Engineering and Science 19 College of Health and Biomedicine 20 College of Law and Justice 22 College of Sport and Exercise Science 23 VU College 24 VU Research 27 University Medals for Academic Excellence 32 University Medals for Academic Excellence in Research Training 32 Companion of the University 33 Honorary Graduates of the University 1987–2019 34 2 VICTORIA UNIVERSITY GRADUATION PROGRAM DECEMBER 2019 AND MARCH 2020 OUR VALUE PROPOSITION TO OUR STUDENTS AND THE COMMUNITY Victoria University (VU) aims to be a great university of the 21st century by being inclusive rather than exclusive. We will provide exceptional value to our diverse community of students by guiding them to achieve their career aspirations through personalised, flexible, well- supported and industry relevant learning opportunities. Achievement will be demonstrated by our students’ and graduates’ employability and entrepreneurship. The applied and translational research conducted by our staff and students will enhance social and economic outcomes in our heartland communities of the West of Melbourne and beyond. -

Archived Listing of New Associates of the Society of Actuaries

New Associates – December 2012 It is a pleasure to announce that the following 145 candidates have completed the educational requirements for Associateship in the Society of Actuaries. 1. Aagesen, Kirsten Greta 2. Andrews, Christopher Lym 3. Arnold, Tiffany Marie 4. Aronson, Lauren Elizabeth 5. Arredondo Sanchez, Jose Antonio 6. Audet, Maggie 7. Audy, Laurence 8. Axene, Joshua William 9. Baik, NyeonSin 10. Barhoumeh, Dana Basem 11. Bedard, Nicolas 12. Berger, Pascal 13. Boussetta, Fouzia 14. Breslin, Kevin Patrick 15. Brian, Irene 16. Chan, Eddie Chi Yiu 17. Chu, James Sunjing 18. Chung, Rosa Sau-Yin 19. Colea, Richard 20. Czabaniuk, Lydia 21. Dai, Weiwei 22. Davis, Gregory Kim 23. Davis, Tyler 24. El Shamly, Mohamed Maroof 25. Elliston, Michael Lee 26. Encarnacion, Jenny 27. Feest, Jared 28. Feller, Adam Warren 29. Feryus, Matthew David 30. Foreshew, Matthew S 31. Forte, Sebastien 32. Fouad, Soha Mohamed 33. Frangipani, Jon D 34. Gamret, Richard Martin 35. Gan, Ching Siang 36. Gao, Cuicui 37. Gao, Ye 38. Genal, Matthew Steven Donald 39. Gontarek, Monika 40. Good, Andrew Joseph 41. Gray, Travis Jay 42. Gu, Quan 43. Guyard, Simon 44. Han, Qi 45. Heffron, Daniel 46. Hu, Gongqiang 47. Hui, Pok Ho 48. Jacob-Roy, Francis 49. Jang, Soojin 50. Jiang, Longhui 51. Kern, Scott Christopher 52. Kertzman, Zachary Paul 53. Kim, Janghwan 54. Kimura, Kenichi 55. Knopf, Erin Jill 56. Kumaran, Gouri 57. Kwan, Wendy 58. Lai, Yu-Tsen 59. Lakhany, Kamran 60. Lam, Kelvin Wai Kei 61. Larsen, Erin 62. Lautier, Jackson Patrick 63. Le, Thuong Thi 64. LEE, BERNICE YING 65. -

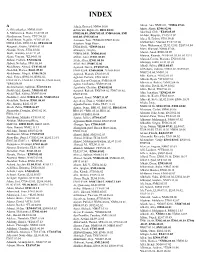

A, Shivashankar, NM05.10.09 A. Mohammed, Mona, EL07

INDEX Akrap, Ana, NM03.01, *NM03.07.03 A Aduda, Bernard, NM04.06.01 Akriti, Akriti, EN06.02.06 A, Shivashankar, NM05.10.09 Advincula, Rigoberto, BI01.04.03, Akselrod, Gleb, *EL05.05.05 A. Mohammed, Mona, EL07.05.05 SM02.06.01, SM07.05.05, SM08.04.06, SM1 Al-Abri, Ruqaiya, CT05.13.02 Abadizaman, Farzin, CT07.04.05 0.03.03, SM13.02.04 Alaca, B. Erdem, ST01.09.01 Abad Mayor, Begoña, *CT03.04.01, Aernouts, Tom, *EN06.01/EN07.01.02 Alahbakhshi, Masoud, EL02.07.06 NM08.01.06, ST01.10.02, ST03.04.02 Aetukuri, Naga Phani, Alam, Muhammad, EL02.12.05, EL09.10.04 Abagnale, Giulio, *SM01.01.05 EN04.08.02, *EN09.04.04 Alam, Shamsul, NM06.07.06 Abando, Nerea, ST02.03.04 Afanasiev, Dmytro, Alamri, Amal, EN03.08.09 Abate, Antonio, EL02.11.04 *NM06.04.01, NM06.08.01 Alarcon, Ricardo, *EL04.04.03, EL04.13.12 Abate, Vincent, *EL04.01.06 Afshar, Amir, EN01.08.09 Alarcon-Correa, Mariana, EN01.03.02 Abbasi, Pedram, EN10.04.04 Aftab, Alina, EN01.04.10 Alarousu, Erkki, EL01.01.03 Abbott, Nicholas, ST01.08.04 Afzal, Atif, SM05.12.02 Albadi, Salwa, SM13.01.05 Abdelkawy, Ahmed, CT01.02.03 Agarwal, Garvit, CT05.07.01, Al Balushi, Zakaria, NM07.08, NM07.09, Abdellah, Marwa, EL01.09.01 EN08.02.04, EN08.04.04, *EN08.06.01 NM07.10.04, NM07.14 Abdelsamie, Maged, EN06.10.26 Agarwal, Manish, EN03.09.33 Albe, Karsten, *ST02.01.01 Abdi, Fatwa, EN02.01, EN02.02, Aghdasi, Parham, ST03.04.03 Alberdi, Ryan, *ST03.07.01 EN02.02.05, EN02.04, EN02.06, EN02.06.02, Agno, Karen-Christian, SM05.06.09 Alberstein, Robert, *SM12.04.05 *EN02.06.09 Agnus, Guillaume, NM09.03.04 Albertini, -

11.Authorindex ADA 12.Indd

ABSTRACT AUTHOR INDEX The number following the name refers to the abstract number, not the page number. A number in bold indicates the author is the abstract presenter. 901 Study Group, 292-OR Adamska, Agnieszka, 494-P, 2860-PO, 2875-PO, Akhmetjanova, Ulmeken A., 2910-PO Aakhus, Svend, 2208-PO 2886-PO Akhoundsadegh, Noushin, 1559-P Abate, Nicola, 1544-P, 1583-P, 1684-P, 2000-P Adamska, Edyta, 2006-P Akhtar, Irfan, 122-OR Abbas, Afroze, 1592-P Adamski, Jerzy, 1600-P, 2279-PO Aki, Nanako, 634-P Abbas, Zulfi qarali G., 653-P AdDIT Study Group, 542-P Akins, Jim, 1859-P Abbasi, Fahim, 1526-P Adeli, Khosrow, 50-OR Akinwale, Abumere, 257-OR Abbott, J. Dawn, 332-OR Adelman, Alan, 343-OR Akirav, Eitan M., 1554-P, 2075-P Abboud, Hanna E., 1548-P Ademoglu, Esranur, 2388-PO Akiyama, Masaru, 203-OR ABCD Nationwide Liraglutide Audit Contributors, Adhya, Sumona, 901-P Akiyama, Takateru, 2852-PO 1038-P, 1113-P Adi, Saleh, 1378-P Akiyama, Yoshitaka, 1138-P Abcouwer, Steven F., 264-OR Adler, Amanda I., 298-OR, 307-OR, 612-P Aksakal, Ilyas, 2242-PO Abdel Mottalib, Adham, 2896-PO Admane, Karim, 1124-P, 2012-P, 2466-PO Al Massadi, Omar, 2865-PO Abdella, Aly, 2613-PO Admiraal, Wanda, 1963-P Al Saeed, Abdulghani, 336-OR ABSTRACT AUTHOR INDEX Abdelmoneim, Ahmed, 1334-P ADMIRE Study Group, 684-P Alagesan, Senthilkumar, 1110-P Abdelmoneim, Sahar S., 940-P Adu, Akosua, 1140-P Alam, Muhammad R., 2118-P Abdul-Ghani, Muhammad, 334-OR, 933-P Aeberli, Isabelle, 2797-PO Alam, Uazman, 764-P, 2260-PO Abdul-Hay, Samer O., 2442-PO Aerni-Flessner, Lauren B., 984-P Alattar, -

Meet the 2020 Young Leaders REGISTER TODAY! Go.Otcnet.Org/Signup Offshore Technology Conference 2020 4–7 MAY » HOUSTON, TEXAS, USA

MARCH 2020 jom.tms.org JAn officialO publication of The Minerals, Metals & Materials Society HONORING ACHIEVEMENT & PROMISE: Meet the 2020 Young Leaders REGISTER TODAY! go.otcnet.org/SignUp Offshore Technology Conference 2020 4–7 MAY » HOUSTON, TEXAS, USA The Offshore Technology Conference (OTC) is where energy professionals meet to exchange ideas and opinions to advance scientific and technical knowledge for offshore resources and environmental matters. HERE’S WHAT OTC CAN OFFER YOU INTERNATIONAL TRADE: Opportunities VALUE: Ground-breaking innovations and for countries to connect and meet with the leading providers of products and international buyers. services in one place, at one time. QUALITY: Technical program selected NETWORKING: Meet people from around by knowledgeable and experienced the world who have ideas to share and professionals. technical knowledge to exchange. 12932 OTC20 Register 8.25x11 2019-12-02c.indd 1 12/2/19 11:00 AM Structural Materials Division JOM Best Paper Award I’VE SPECIALIZED “Effect of TiN-Particles on Fracture of Press- FOR 40 YEARS Hardened Steel Sheets in the placement of Metallurgical, and Components,” Materials, and Welding Engineers in J.C. Pang, H.L. Yi, Q. Lu, the areas of R&D, Q.C. Production, C.M. Enloe, and J.F. Wang 71, 1329–1337 (2019) Sales & Marketing, nationwide. doi: 10.1007/s11837-018-3308-z My background as a Light Metals Division Met. Eng. can help you! JOM Best Paper Award Salaries to $190K. “Al8Mn5 Particle Settling Fees paid by Company. and Interactions with Oxide Films in Liquid AZ91 Michael Heineman, Magnesium Alloys,” L. Peng, G. Zeng, T.C. -

Key to Authors and Presiders (Bold Denotes Presider Or Presenting Author)

Key to Authors and Presiders (Bold denotes Presider or Presenting Author) Abashin, Maxim-QTuH6 Al-Kadry, Alaa-CThD3 Aras, Mehmet-CFA4, QFB6, QTuI6 Badolato, Antonio-QWC5 Abbott, Derek-CThN3 Al-hemyari, Kadhair-AMC5, AWA3 Aravazhi, Shanmugam-CWP4 Bae, Hopil-CFL4 Abdel-Fattah, Mahmoud-QTuN3 Alam, Muhammad-JWA111 Arbabi, Amir-JTuI25 Bae, Joonwoo-QThO4 Abedin, Kazi S-CMS, CMZ3 Alam, Shaif-ul-CThDD5, CTuI1, CTuX1, Arbel, David-JMF5 Baek, Burm-JTuA2, QWA7 Abel, Keith-JThB30 JWA120 Arce, Gonzalo-ATuE2 Baek, Jong-Hyeob-CMCC6 Abel, Mark J-QMG4 Alamarguy, David-JTuD5 Arcizet, Olivier-QFH6, QThM1, QThM2, Baer, Cyrill-CFO1, CMJ1, CWP1 Abell, Joshua-CTuC3 Alanko, Jukka-Pekka-CTuC5 QWG5 Baer, Eric-JWA73 Abid, Mohamed-JTuD5 Albert, Jacques-CMZ, CThL3, CThL6, Arepalli, Sivaram-QWH5 Baets, Roel-CTuS1, CTuS2 Abolghasem, Payam-QThN2, QWA5 CTuI3, CTuL6 Ares, Richard-QMI1 Bagnell, Marcus-CWQ6 Abouraddy, Ayman-QThD6 Alden, Marcus-CThCC3 Arisholm, Gunnar-JThB66 Bahabad, Alon-CMR1 Abraham, Emmanuel-CThV6 Alduino, Andrew-CThP5 Arissian, Ladan-QThI2, QThI3 Bahat-Treidel, Omri-QThD1 Abram, Izo-QFE4, QFG2 Alessi, David-QTuC6 Arju, Nihal-QFA3 Bahl, Gaurav-QWE3 Abramski, Krzysztof M-CMBB2 Alex, Boeglin-JWA75 Arkin, Meredith-JThA1 Bahrami, Farshid-JWA111 Abreu, Elsa-QWD1 Alexander, Tristram J-QMD2 Arlunno, Valeria-CThO5 Bai, Ping-QTuL2 Abshire, James B-ATuA2, ATuA4, JTuE5 Alexander, Vinay-CThD2 Armen, Michael A-QThB3 Baili, Ghaya-JThB65 Abtahi, Mohammad-CThY4 Alfano, Robert-CThAA2 Arnold, Craig B-AMB, AMD2, JMG3, Bakarezos, Makis-QMC6 Acar, Handan-CMX4 Alfano, Robert -

Bibliography of Chinese Linguistics William S.-Y.Wang

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF CHINESE LINGUISTICS WILLIAM S.-Y.WANG INTRODUCTION THIS IS THE FIRST LARGE-SCALE BIBLIOGRAPHY OF CHINESE LINGUISTICS. IT IS INTENDED TO BE OF USE TO STUDENTS OF THE LANGUAGE WHO WISH EITHER TO CHECK THE REFERENCE OF A PARTICULAR ARTICLE OR TO GAIN A PERSPECTIVE INTO SOME SPECIAL TOPIC OF RESEARCH. THE FIELD OF CHINESE LINGUIS- TICS HAS BEEN UNDERGOING RAPID DEVELOPMENT IN RECENT YEARS. IT IS HOPED THAT THE PRESENT WORK WILL NURTURE THIS DEVELOP- MENT BY PROVIDING A SENSE OF THE SIZABLE SCHOLARSHIP IN THE FIELD» BOTH PAST AND PRESENT. IN SPITE OF REPEATED CHECKS AND COUNTERCHECKS, THE FOLLOWING PAGES ARE SURE TO CONTAIN NUMEROUS ERRORS OF FACT, SELECTION AND OMISSION. ALSO» DUE TO UNEVENNESS IN THE LONG PROCESS OF SELECTION, THE COVERAGE HERE IS NOT UNIFORM. THE REPRESENTATION OF CERTAIN TOPICS OR AUTHORS IS PERHAPS NOT PROPORTIONAL TO THE EXTENT OR IMPORTANCE BIBLIOGRAPHY OF CHINESE LINGUISTICS ]g9 OF THE CORRESPONDING LITERATURE. THE COVERAGE CAN BE DIS- CERNED TO BE UNBALANCED IN TWO MAJOR WAYS. FIRST. THE EMPHASIS IS MORE ON-MODERN. SYNCHRONIC STUDIES. RATHER THAN ON THE WRITINGS OF EARLIER CENTURIES. THUS MANY IMPORTANT MONOGRAPHS OF THE QING PHILOLOGISTS. FOR EXAMPLE, HAVE NOT BEEN INCLUDED HERE. THOUGH THESE ARE CERTAINLY TRACE- ABLE FROM THE MODERN ENTRIES. SECOND, THE EMPHASIS IS HEAVILY ON THE SPOKEN LANGUAGE, ALTHOUGH THERE EXISTS AN ABUNDANT LITERATURE ON THE CHINESE WRITING SYSTEM. IN VIEW OF THESE SHORTCOMINGS, I HAD RESERVATIONS ABOUT PUBLISHING THE BIBLIOGRAPHY IN ITS PRESENT STATE. HOWEVER, IN THE LIGHT OF OUR EXPERIENCE SO FAR, IT IS CLEAR THAT A CONSIDERABLE AMOUNT OF TIME AND EFFORT IS STILL NEEDED TO PRODUCE A COMPREHENSIVE BIBLIOGRAPHY THAT IS AT ONCE PROPERLY BALANCED AMD COMPLETELY ACCURATE (AND, PERHAPS, WITH ANNOTATIONS ON THE IMPORTANT ENTRIES). -

新成立/ 註冊及已更改名稱的公司名單list of Newly Incorporated

This is the text version of a report with Reference Number "RNC063" and entitled "List of Newly Incorporated /Registered Companies and Companies which have changed Names". The report was created on 24-05-2021 and covers a total of 2027 related records from 17-05-2021 to 23-05-2021. 這是報告編號為「RNC063」,名稱為「新成立 / 註冊及已更改名稱的公司名單」的純文字版報告。這份報告在 2021 年 5 月 24 日建立,包含從 2021 年 5 月 17 日到 2021 年 5 月 23 日到共 2027 個相關紀錄。 Each record in this report is presented in a single row with 6 data fields. Each data field is separated by a "Tab". The order of the 6 data fields are "Sequence Number", "Current Company Name in English", "Current Company Name in Chinese", "C.R. Number", "Date of Incorporation / Registration (D-M-Y)" and "Date of Change of Name (D-M-Y)". 每個紀錄會在報告內被設置成一行,每行細分為 6 個資料。 每個資料會被一個「Tab 符號」分開,6 個資料的次序為「順序編號」、「現用英文公司名稱」、「現用中文公司名稱」、「公司註冊編號」、「成立/ 註冊日期(日-月-年)」、「更改名稱日期(日-月-年)」。 Below are the details of records in this report. 以下是這份報告的紀錄詳情。 1. 10x1000 Limited 2733477 21-05-2021 2. 110 Black Cloud Trading Co., Limited 110 黑雲貿易有限公司 3048993 17-05-2021 3. 23.59 LIMITED 貳參伍玖有限公司 3049205 17-05-2021 4. 2vanpower Company Limited 3050403 21-05-2021 5. 3D Technology Application Association Limited 立體科技應用協會有限公司 3049901 20-05-2021 6. 510 CLINIC LIMITED 3050179 21-05-2021 7. 5151 RATINGS (INTERNATIONAL) CO., LIMITED 五一五一評級(國際)有限公司 3048995 17-05-2021 8. A Sense Of Partners Group Limited 宏斯集團有限公司 3049816 20-05-2021 9. A&K eCommerce Limited 3050362 21-05-2021 10. -

2011 International Symposium on Water Resource and Environmental Protection

2011 International Symposium on Water Resource and Environmental Protection (ISWREP 2011) Xi’an, Shaanxi Province, China 20 - 22 May 2011 Volume 1 Pages 1-818 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP1145N-PRT ISBN: 978-1-61284-339-1 1/4 TABLE OF CONTENTS VOL.01 1-Groudwater Sci & Tech1 0001-1199 SUPERGENE ECOLOGICAL EFFECTS INDUCED BY GROUNDWATER AND ITS 1 THRESHOLDS IN THE ARID AREAS Wenke Wang, Zeyuan Yang, Jinling Kong, Lei Duan, Donghui Cheng, Guizhang Zhao 0002-0139 APPLICATION OF MUTI-QUADRIC INTERPOLATION IN NUMERICAL 9 SIMULATION OF 2D GROUNDWATER FLOW LONG Yu-qiao, YANG Zhong-ping ,HOU Li-li, LI Wei , LI Yan-ge 0003-0145 WATER -ROCK INTERACTION SIMULATION OF GROUNDWATER IN THE 16 YONGDING RIVER ALLUVIAL FAN OF BEIJING PLAIN Huan Huan, Jinsheng Wang, Jieqiong Zheng, Yuanzheng Zhai 0004-0172 FUZZY COMPREHENSIVE EVALUATION OF GROUNDWATER POLLUTION IN 20 COAL MINING AREA Runsheng LV ,Bo LI, Yanyong XU 0005-0223 HYDRODYNAMIC AND HYDROCHEMICAL STUDY OF WATER IN A KARST 24 AQUIFER-A CASE STUDY IN HOUZHAI KARSTIC WATER SYSTEM, GUIZHOU PROVINCE, CHINA Lihong Liu ,Xunhong Chen 0006-0239 A COMBINED CONCEPTUAL MODEL (V&P MODEL) TO CORRECT 28 GROUNDWATER RADIOCARBON AGE Tianming Huang ,Zhonghe Pang 0007-0248 OCCURRENCE FEATURES AND LEACHING MIGRATION OF CHLOROFORM 31 IN SHALLOW GROUNDWATER LI Ya-song, ZHANG Zhao-ji, FEI Yu-hong, WANG Zhao, QIAN Yong, CHEN Jing-sheng, ZHANG Feng-e 0008-0266 STUDY ON POLLUTION PLUME CONTROL AND REMOVAL EFFICIENCY OF 35 CHLOROBENZENE IN GROUNDWATER BY AIR SPARGING QIN Chuanyu ,ZHAO Yongsheng, ZHENG Wei 0009-0269 STUDY ON TRANSBOUNDARY -

Curriculum Vitae Baofeng Yang

Curriculum Vitae Baofeng Yang, PhD Harbin Medical University CONTENTS PERSONAL DETAILS ........................................................................................................................................... 3 CURRENT POSITIONS ......................................................................................................................................... 3 EDUCATION AND QUALIFICATIONS .............................................................................................................. 3 AWARDS AND PRIZES ......................................................................................................................................... 3 APPOINTMENTS ................................................................................................................................................... 6 RESEARCH FUNDING .......................................................................................................................................... 7 HONORARY TITLES .......................................................................................................................................... 10 CONFERENCE ORGANISING COMMITTEES / SCIENTIFIC PROGRAM COMMITTEES ................. 11 GRANT REVIEWS ............................................................................................................................................... 13 EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERSHIP ............................................................................................................... 13 PEER -

November 2018

November 2018 November Vol. 845 Innovation in CIIE International Trade 国内零售价: 10元 USA $5.10 UK ₤3.20 12-14 58-61 72-77 Australia $9.10 Europe €5.20 Canada $7.80 Turkey TL.10.00 A New Day in Bittersweet Typhoon Landscapes of Rural China Mangkhut the Mind 2-903 CN11-1429/Z 邮发代号 可绕地球赤道栽种树木按已达塞罕坝机械林场的森林覆盖率寒来暑往,沙地变林海,荒原成绿洲。半个多世纪,三代人耕耘。牢记使命 80% , 1 米株距排开, 艰苦创业 12 圈。 绿色发展 Saihanba is a cold alpine area in northern Hebei Province bordering the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. It was once a barren land but is now home to 75,000 hectares of forest, thanks to the labor of generations of forestry workers in the past 55 years. Every year the forest purifies 137 million cubic meters of water and absorbs 747,000 tons of carbon dioxide. The forest produces 12 billion yuan (around US$1.8 bil- lion) of ecological value annually, according to the Chinese Academy of Forestry. Nov 2O18 Administrative Agency: China International Publishing Group 主管:中国外文出版发行事业局 (中国国际出版集团) Publisher: China Pictorial Publications 主办: 社 Address: 33 Chegongzhuang Xilu 社址: Haidian, Beijing 100048 北京市海淀区车公庄西路33号 邮编: 100048 Email: [email protected] : [email protected] 邮箱 President: Yu Tao 社长: 于 涛 Editorial Board: Yu Tao, Li Xia, He Peng 编委会: Bao Linfu, Yu Jia, Yan Ying 于 涛、李 霞、贺 鹏 鲍林富、于 佳、闫 颖 Editor-in-Chief: Li Xia 总编辑: 李 霞 Editorial Directors: Wen Zhihong, Qiao Zhenqi 编辑部主任: 温志宏、乔振祺 English Editor: Liu Haile 英文定稿: 刘海乐 Editorial Consultants: Scott Huntsman, Mithila Phadke 语言顾问: 苏 格、弥萨罗 Editors and Translators: Gong Haiying, Yin Xing 编辑、翻译: Zhao Yue,