Ethnographic Symbols in Latvian Regional Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 12, 1992 Prepared By: Clyde Hertzman MD

OM TRIP REPORT ON ENVIRONMENT & HEALTH IN THE BALTIC COUNTRIES January 11 - February 12, 1992 Prepared by: Clyde Hertzman MD, MSc, FRCPC WORLD ENVIRONMENT CENTER 419 Park Avenue South, Suite 1800 New York, NY 10016 May 1992 DISCLAIMER The opinions expressed herein are the professional opinions of the author and do not represent the official position of the Government of the United States or the World Environment Center. Environment and Health in the Faltic Countries by Clyde Hertzman MD, MSc, FRCPC My investigations into environmental health conditions in Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia were the first I conducted in republics of the former Soviet Union. In comparison to Poland. Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Bulgaria (herein, the non-Soviet republics or Central Europe) which 1previously investigated, they were notable for a general lack of useful data on the human health impact of environmental pollution. This difference could not be attributed to an absence of public health agencies similar to those found in the non- Soviet republics since, in a superficial sense, the institutional structures are quite similar all across Central and Eastern Europe. However, the Baltic republics seemed to have additional obstacles to the effective evaluation of environmental health problems not encountered in Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Bulgaria. In the Baltics, the agencies responsible for environmental measurement and public health investigation tended to have stronger reporting relationships with Moscow than with each other. This lead to alow degree of inter-agency co-operation and made the agencies susceptible to manipulation according to interests which conflicted with their (theoretical) mandate to protect the public's health. -

World Bank Document

35846 v 1 Public Disclosure Authorized Assessing Intergovernmental Fiscal Relations Financing Higher Education Controlling Health Care Expenditures Managing Fiscal Risks in Public-Private Partnerships Public Disclosure Authorized VOLUME I: MAIN REPORT VOLUME II: COUNTRY CASE STUDIES (CD) Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Contents FOREWORD ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Daniela Gressani CONTRIBUTORS ................................................................................................................................ 9 CONFERENCE AGENDA ...................................................................................................................... 10 OVERVIEW ....................................................................................................................................... 11 Thomas Laursen I. FISCAL CHALLENGES FOR THE EU8 COUNTRIES ......................................................................... 27 Paulina Bucon and Emilia Skrok 1. FISCAL DEVELOPMENTS 1995-2004 ........................................................................................ 27 2. MEDIUM-LONG TERM FISCAL PROSPECTS ............................................................................... 43 3. QUALITY OF FISCAL POLICY ..................................................................................................... 46 II. INTERGOVERNMENTAL FISCAL RELATIONS .............................................................................. -

Health Systems in Transition

61575 Latvia HiT_2_WEB.pdf 1 03/03/2020 09:55 Vol. 21 No. 4 2019 Vol. Health Systems in Transition Vol. 21 No. 4 2019 Health Systems in Transition: in Transition: Health Systems C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Latvia Latvia Health system review Daiga Behmane Alina Dudele Anita Villerusa Janis Misins The Observatory is a partnership, hosted by WHO/Europe, which includes other international organizations (the European Commission, the World Bank); national and regional governments (Austria, Belgium, Finland, Kristine Klavina Ireland, Norway, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the Veneto Region of Italy); other health system organizations (the French National Union of Health Insurance Funds (UNCAM), the Dzintars Mozgis Health Foundation); and academia (the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) and the Giada Scarpetti London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM)). The Observatory has a secretariat in Brussels and it has hubs in London at LSE and LSHTM) and at the Berlin University of Technology. HiTs are in-depth profiles of health systems and policies, produced using a standardized approach that allows comparison across countries. They provide facts, figures and analysis and highlight reform initiatives in progress. Print ISSN 1817-6119 Web ISSN 1817-6127 61575 Latvia HiT_2_WEB.pdf 2 03/03/2020 09:55 Giada Scarpetti (Editor), and Ewout van Ginneken (Series editor) were responsible for this HiT Editorial Board Series editors Reinhard Busse, Berlin University of Technology, Germany Josep Figueras, European -

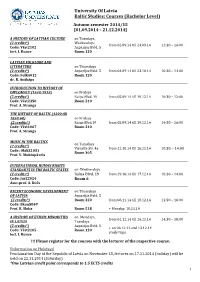

University of Latvia Baltic Studies: Courses (Bachelor Level)

University Of Latvia Baltic Studies: Courses (Bachelor Level) Autumn semester 2014/15 [01.09.2014 – 21.12.2014] A HISTORY OF LATVIAN CULTURE on Tuesdays, (2 credits*) Wednesdays from 02.09.14 till 24.09.14 12:30 – 16:00 Code: Vēst2102 Azpazijas Bvld. 5 lect. I. Runce Room 120 LATVIAN FOLKLORE AND LITERATURE on Thursdays (2 credits*) Azpazijas Bvld. 5 from 04.09.14 till 23.10.14 10:30 – 14:00 Code: Folk4012 Room 120 dr. R. Auškāps INTRODUCTION TO HISTORY OF DIPLOMACY (1648-1918) on Fridays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd. 19 from 05.09.14 till 19.12.14 10:30 – 12:00 Code: Vēst2350 Room 210 Prof. A. Stranga THE HISTORY OF BALTIC (1200 till 1850-60) on Fridays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd.19 from 05.09.14 till 19.12.14 14:30 – 16:00 Code: Vēst1067 Room 210 Prof. A. Stranga MUSIC IN THE BALTICS on Tuesdays (2 credits*) Visvalža Str. 4a from 21.10.14 till 16.12.14 10:30. – 14:00 Code : MākZ1031 Room 305 Prof. V. Muktupāvels INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS STANDARTS IN THE BALTIC STATES on Wednesdays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd. 19 from 29.10.14 till 17.12.14 10:30 – 14:00 Code: JurZ2024 Room 6 Asoc.prof. A. Kučs RECENT ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT on Thursdays OF LATVIA Azpazijas Bvld. 5 (2 credits*) Room 320 from 06.11.14 till 18.12.14 12:30 – 16:00 Code: Ekon5069 Prof. B. Sloka Room 518 + Monday, 10.11.14 A HISTORY OF ETHNIC MINORITIES on Mondays, from 01.12.14 till 16.12.14 14:30 – 18:00 IN LATVIA Tuesdays (2 credits*) Azpazijas Bvld. -

Download Download

ESUKA – JEFUL 2014, 5–1: 27–36 LIVONIAN LANDSCAPES IN THE HISTORICAL GEOGRAPHY OF LIVONIA AND THE DIVISION OF THE LIVONIAN TRIBES Urmas Sutrop Institute of the Estonian Language, Tallinn, and the University of Tartu Abstract. There is no exact consensus on the division and sub-division of the former Livonian territories at the end of the ancient independence period in the 12th century. Even the question of the Coastal Livonians in Courland – were they an indigenous Livonian tribe or a replaced eastern Livonian tribe – remains unsolved. In this paper the anonymously published treatise on the historical geography of Livonia by Johann Christoph Schwartz (1792) will be analysed and compared with the historical modern views. There is an agreement on the division of the Eastern Livonian territories into four counties: Daugava, Gauja, Metsepole, and Idumea. Idumea had a mixed Livo- nian-Baltic population. There is no consensus on the parochial sub-division of these counties. Keywords: Johann Christoph Schwartz, historical geography, Livonian tribes, Livonians DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12697/jeful.2014.5.1.02 1. Introduction It is commonly believed that Livonians (like Estonians) did not form either territorial or political unity at the end of the ancient independence period in the 12th century (see e.g. Koski 1997: 45). The first longer document where Livonians are described is the Livonian Chronicle (Heinrici Cronicon Lyvoniae) for the period 1180 to 1227 written by Henry of Livonia, an eyewitness of these events. Modern ideas on the division of Eastern Livonian peoples and territories go back to the cartographic work of Heinrich Laakmann, who divided Livonians into three territories – Daugava, Thoreida, and Metsepole; and added that there was a mixed Livonian-Baltic population at the end of the 12th century in Idumea (see the map Baltic Lands: population about 1200 AD and explanation to this map in Laakmann 1954). -

Personal Names and Denomination of Livonians in Early Written Sources

ESUKA – JEFUL 2014, 5–1: 13–26 PERSONAL NAMES AND DENOMINATION OF LIVONIANS IN EARLY WRITTEN SOURCES Enn Ernits Estonian University of Life Sciences Abstract. This paper presents the timeline of ethnonyms denoting Livonians; specifies their chronology; and analyses the names used for this ethnos and possible personal names. If we consider the dating of the event, the earliest sources mentioning Livonians are Gesta Danorum and the Tale of Bygone Years (both 10th century), but both sources present rather dubious information: in the first the battle of Bråvalla itself or the date are dubious (6th, 8th or 10th century); in the latter we cannot be sure that the member of the Rus delegation was really a Livonian. If we consider the time of recording, the earliest sources are two rune inscriptions from Sweden (11th century), and the next is the list of neighbouring peoples of the Russians from the Tale of Bygone Years (12th century). The personal names Bicco and Ger referred in Gesta Danorum, and Либи Аръфастовъ in Tale of Bygone Years are very problematic. The first certain personal name of a Livonian is *Mustakka, *Mustukka or *Mustoikka (from Finnic *musta ‘black’) written in 1040–1050s on a strip of birch bark in Novgorod. Keywords: Livs, Finnic peoples, ethnonyms, anthroponyms, onomastics DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12697/jeful.2014.5.1.01 1. Introduction This paper (1) seeks to present the timeline of ethnonyms denoting Livonians; (2) to specify their chronology; (3) and to analyse the names used for this ethnos and possible personal names. It is supple- mental to the paper by Mauno Koski on words denoting Livonians (Koski 2011). -

Same-Sex Relationships: Why Do Many Latvian Politicians Resist Them?

SSE Riga Student Research Papers 2021 : 2 (234) SAME-SEX RELATIONSHIPS: WHY DO MANY LATVIAN POLITICIANS RESIST THEM? Authors: Daniela Gerda Baranova Samanta Mežmale ISSN 1691-4643 ISBN 978-9984-822-58-7 May 2021 Riga Same-Sex Relationships: Why Do Many Latvian Politicians Resist Them? Daniela Gerda Baranova and Samanta Mežmale Supervisor: Xavier Landes May 2021 Riga Table of Contents List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................................. 5 Abstract ....................................................................................................................................... 6 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 7 2. Literature Review .................................................................................................................. 9 2.1. LGBT in the World ......................................................................................................... 9 2.1.1. LGBT Movement ....................................................................................................... 9 2.1.2. Legislation ................................................................................................................ 10 2.1.3. Sexual orientation discrimination and homophobia ................................................. 11 2.1.4. Supporting organisations ......................................................................................... -

BALTIC SUSTAINABLE ENERGY STRATEGY Stockholm Environment Institute Tallinn Centre

BALTIC SUSTAINABLE ENERGY STRATEGY Stockholm Environment Institute Tallinn Centre Tallinn-Riga-Kaunas, 2008 This strategy is prepared during the project "Baltic-Nordic cooperation for sustainable energy" that is a joint cooperation project of environmental NGOs and experts from Baltic and Nordic countries, North-West Russia and Belarus. The project is financially supported by the Nordic Council of Ministers. Project was coordinated by the Latvian Green Movement (www.zalie.lv). Strategy was prepared by Stockholm Environment Institute Tallinn Centre (www.seit.ee) and was discussed and amended by the participants of the international seminar "Sustainable energy policy for the Baltic Sea region: non-fossil and non-nuclear opportunities" that took place on February 26, 2008 in Riga, Latvia. 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………….6 2. Baltic States power sector developments….……………………………………………8 2.1. General characteristics………………………………………………..…………….....8 2.2. Estonia………………………………………………………………………………..10 2.3. Latvia…………………………………………………………………………………19 2.4. Lithuania………………………………………………………………………….…..26 2.5. Energy intensity of Baltic States..……………………………………………………33 3. Goals for the Energy sector in the Baltic States………………………………………36 4. Sustainable Energy Strategy for Baltic States…………………………………………41 4.1. Sustainable energy indicators………………………………………………………...43 4.2. External costs of energy production………………………………………………….48 4.3. Goals of the Baltic Sustainable Energy Strategy……………………………………..52 4.4. Measures to achieve BSES Goals……………………………………………………53 -

Latvia Towards Europe: Internal Security Issues

North Atlantic Treaty Organization Andris Runcis LATVIA TOWARDS EUROPE: INTERNAL SECURITY ISSUES Final Report The preparation of this Report was made possible through a NATO Award. Rîga, 1999 1 Content Introduction 3 1. The basic aspects of a country’s security 5 2. Latvia’s security concept 8 3. Corruption 10 4. Unemployment 17 5. Non-governmental organizations 19 6. The Latvian banking system and its crisis 27 7. Citizenship issue 32 Conclusion 46 Appendix 48 2 Introduction The security of small countries has been a difficult problem since ancient times. Now, when the Cold War has ended and Europe has moved from a bipolar to a multipolar system, when the communist system in Eastern Europe has collapsed and the Soviet empire has disintegrated – processes which have led to the appearance of a series of new and mostly small countries in Europe – we are witnessing a renaissance of small countries in the international arena. Since regaining independence Latvia’s general foreign policy orientation has been associated with integration into European economic, political and military structures where full membership in the European Union (EU) is the cornerstone. The issue has been one of the most consolidated and undisputed on the country’s political agenda. Latvian politicians have stressed the country’s wish to become a member state of the European Union. On October 14, 1995, all political parties represented in the Parliament supported the State President’s proposed Declaration on the Policy of Latvian Integration in the European Union. On October 27, Latvia submitted its application for membership to the EU. -

THE DISCOVERY of the BALTIC the NORTHERN WORLD North Europe and the Baltic C

THE DISCOVERY OF THE BALTIC THE NORTHERN WORLD North Europe and the Baltic c. 400-1700 AD Peoples, Economies and Cultures EDITORS Barbara Crawford (St. Andrews) David Kirby (London) Jon-Vidar Sigurdsson (Oslo) Ingvild Øye (Bergen) Richard W. Unger (Vancouver) Przemyslaw Urbanczyk (Warsaw) VOLUME 15 THE DISCOVERY OF THE BALTIC The Reception of a Catholic World-System in the European North (AD 1075-1225) BY NILS BLOMKVIST BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2005 On the cover: Knight sitting on a horse, chess piece from mid-13th century, found in Kalmar. SHM inv. nr 1304:1838:139. Neg. nr 345:29. Antikvarisk-topografiska arkivet, the National Heritage Board, Stockholm. Brill Academic Publishers has done its best to establish rights to use of the materials printed herein. Should any other party feel that its rights have been infringed we would be glad to take up contact with them. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Blomkvist, Nils. The discovery of the Baltic : the reception of a Catholic world-system in the European north (AD 1075-1225) / by Nils Blomkvist. p. cm. — (The northern world, ISSN 1569-1462 ; v. 15) Includes bibliographical references (p.) and index. ISBN 90-04-14122-7 1. Catholic Church—Baltic Sea Region—History. 2. Church history—Middle Ages, 600-1500. 3. Baltic Sea Region—Church history. I. Title. II. Series. BX1612.B34B56 2004 282’485—dc22 2004054598 ISSN 1569–1462 ISBN 90 04 14122 7 © Copyright 2005 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill Academic Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. -

A Reconstructed Indigenous Religious Tradition in Latvia

religions Article A Reconstructed Indigenous Religious Tradition in Latvia Anita Stasulane Faculty of Humanities, Daugavpils University, Daugavpils LV-5401, Latvia; [email protected] Received: 31 January 2019; Accepted: 11 March 2019; Published: 14 March 2019 Abstract: In the early 20th century, Dievtur¯ıba, a reconstructed form of paganism, laid claim to the status of an indigenous religious tradition in Latvia. Having experienced various changes over the course of the century, Dievtur¯ıba has not disappeared from the Latvian cultural space and gained new manifestations with an increase in attempts to strengthen indigenous identity as a result of the pressures of globalization. This article provides a historical analytical overview about the conditions that have determined the reconstruction of the indigenous Latvian religious tradition in the early 20th century, how its form changed in the late 20th century and the types of new features it has acquired nowadays. The beginnings of the Dievturi movement show how dynamic the relationship has been between indigeneity and nationalism: indigenous, cultural and ethnic roots were put forward as the criteria of authenticity for reconstructed paganism, and they fitted in perfectly with nativist discourse, which is based on the conviction that a nation’s ethnic composition must correspond with the state’s titular nation. With the weakening of the Soviet regime, attempts emerged amongst folklore groups to revive ancient Latvian traditions, including religious rituals as well. Distancing itself from the folk tradition preservation movement, Dievtur¯ıba nowadays nonetheless strives to identify itself as a Latvian lifestyle movement and emphasizes that it represents an ethnic religion which is the people’s spiritual foundation and a part of intangible cultural heritage. -

Revista Romană De Geografie Politică

Revista Română de Geografie Politică Year XXIII, no. 1, June 2021, pp. 1-57 ISSN 1582-7763, E-ISSN 2065-1619 http://rrgp.uoradea.ro, [email protected] REVISTA ROMÂNĂ DE GEOGRAFIE POLITICĂ Romanian Review on Political Geography Year XXIII, no. 1, June 2021 Editor-in-Chief: Alexandru ILIEŞ, University of Oradea, Romania Associate Editors: Voicu BODOCAN, “Babeş-Bolyai” University of Cluj-Napoca, Romania Milan BUFON, "Primorska” University of Koper, Slovenia Jan WENDT, University of Gdansk, Poland Vasile GRAMA, University of Oradea, Romania Scientific Committee: Silviu COSTACHIE, University of Bucharest, Romania Remus CREŢAN, West University of Timişoara, Romania Olivier DEHOORNE, University of the French Antilles and Guyana, France Anton GOSAR, “Primorska” University of Koper, Slovenia Ioan HORGA, University of Oradea, Romania Ioan IANOŞ, University of Bucharest, Romania Corneliu IAŢU, “Al. I. Cuza” University of Iaşi, Romania Vladimir KOLOSSOV, Russian Academy of Science, Russia Ionel MUNTELE, “Al. I. Cuza” University of Iaşi, Romania Silviu NEGUŢ, Academy of Economical Studies of Bucharest, Romania John O’LOUGHLIN, University of Colorado at Boulder, U.S.A. Lia POP, University of Oradea, Romania Nicolae POPA, West University of Timişoara, Romania Stéphane ROSIÈRE, University of Reims Champagne-Ardenne, France Andre-Louis SANGUIN, University of Paris-Sorbonne, France Radu SĂGEATĂ, Romanian Academy, Institute of Geography, Romania Marcin Wojciech SOLARZ, University of Warsaw, Poland Alexandru UNGUREANU, Romanian Academy Member, “Al. I. Cuza” University of Iaşi, Romania Luca ZARRILLI, “G. D’Annunzio” University, Chieti-Pescara, Italy Technical Editor: Grigore HERMAN, University of Oradea, Romania Foreign Language Supervisor: Corina TĂTAR, University of Oradea, Romania The content of the published material falls under the authors’ responsibility exclusively.