Marcraeff, 1923-2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marc Raeff As Correspondent: Letters to Isaiah Berlin, 1950-19731

DOCUMENTS/ G. M. HAMBURG (Claremont, CA, USA) MARC RAEFF AS CORRESPONDENT: LETTERS TO ISAIAH BERLIN, 1950-19731 Marc Raeff (1923-2008) was perhaps the most prolific historian of imperial Russia to be active in the West in the last half century.2 Born in Moscow just after the end of the Russian civil war, educated in Berlin and Paris before coming to the United States in 1941, he was a genuine cos- mopolitan who moved between languages and cultures with ease. At Har- vard University, where he was a student of Michael Karpovich, Raeff specialized in the political and intellectual history of pre-emancipation Russia. His doctoral dissertation analyzed Russian social thought in the 1. I wish to thank Mrs. Lillian Raeff for granting permission to publish Marc Raeff's letters to Isaiah Berlin. Works of Isaiah Berlin are reproduced with permission of Curtis Brown Group Ltd, London on behalf of the Estate of the Isaiah Berlin Literary Trust. Copyright information for Berlin's published works is as follows (Full bibliographical cita- tions can be found in the notes, below): "Historical Inevitability," from Liberty copyright © Isaiah Berlin, 1954, 1969, 1997; "Two Concepts of Liberty," from Liberty, copyright ®Isaiah Berlin, 1958, 1969,_1997; "Montesquieu, " from Against the Current, copyright 0 Isaiah Berlin 1955; Fathers and Children: Turgenev and the Liberal Predicament, copy- right ®Isaiah Berlin, 1970, 1972, 19073, 1975, 1978; The Hedgehog and the Fox, copy- right (j) Isaiah Berlin, 1953; "Joseph de Maistre and Origins of Fascism," from The Crooked Timber of Humanity, Copyright (D The Isaiah Berlin Literary Trust, 2003; "The Silence in Russian Culture," from Foreign Affair 36, copyright © Isaiah Berlin, 1957; "The Soviet Intelligentsia" from Foreign Affair 36, copyright ® Isaiah Berlin 1957. -

March 2021 Issue of Newsnet

NewsNet News of the Association for Slavic, East European and Eurasian Studies March 2021 v. 61, n. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Plots against Russia, 3 An Interview with Eliot Borenstein Building a Network of Support 7 for Undergraduate Students of Color Interested in REEES Uncomfortable Conversations: 11 On Preparing BIPOC University Students for Study in Russia “You’re doing it all wrong:” 15 Course Revision and Planning in mid-career – True Confessions 19 Publications ASEEES Prizes Call for 21 Submissions 25 Institutional Member News 28 Personages 29 In Memoriam 30 Affiliate Group News Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies (ASEEES) 203C Bellefield Hall, 315 S. Bellefield Ave Pittsburgh, PA 15260-6424 tel.: 412-648-9911 • fax: 412-648-9815 www.aseees.org ASEEES Staff Executive Director: Lynda Park 412-648-9788, [email protected] Deputy Director/Director of Membership: Kelly McGee 412- 238-7354, [email protected] NewsNet Editor & Program Coordinator: Trevor Erlacher 412-648-7403, [email protected] Communications Coordinator: Mary Arnstein 412-648-9809, [email protected] Convention Manager: Margaret Manges 412-648-4049, [email protected] Administrative Assistant: Jenn Legler 412-648-9911, [email protected] Financial Support: Roxana L. Espinoza NEWSNET March 2021 1 412-648-4049, [email protected] ASEEES RESEARCH GRANTS ASEEES DISSERTATION RESEARCH GRANTS fund doctoral dissertation research in Eastern Europe and Eurasia in any aspect of SEEES in any discipline. Thanks to generous donations, we are offering several grants in Women and Gender Studies, LGBTQ Studies, and in Russian Studies. Applicants may be students of any nationality, in any discipline, currently enrolled in a PhD program in the US. -

Hamburgm CV 2019

Name: Gary Michael Hamburg Office: History Department Home, Claremont: 468 Potomac Way 850 Columbia Avenue Claremont, CA 91711 Claremont McKenna College Home, South Bend: 1430 East Wayne St. Claremont, CA 91711 South Bend, IN 46615 (909) 624-6490. (574) 261-5271 cell. Email: [email protected] Education: A.B. with distinction, Stanford University, 1972; A.M. in History, Stanford University, 1974; Ph.D. in History, Stanford University, 1978. Foreign study at Leningrad State University, USSR, 1971-1972 (Fall Semester) and 1975- 1976 (Academic Year); at Moscow University, 1986; in Moscow, 1992. Employment and Teaching: Teaching and Research Fellow, Stanford University, 1977-1978; Assistant Professor of History, Cornell College, 1978-1979; Assistant Professor of History, University of Notre Dame, 1979-1985; Associate Professor, University of Notre Dame, 1985-1993; Professor of History, University of Notre Dame, 1993 to 2004; Recipient, Kaneb Award for Outstanding Teaching, University of Notre Dame, 2003. Otto M. Behr Professor of European History, Claremont McKenna College, 2004 to present. Roy P. Crocker Award for Merit (awarded by the faculty), 2011 – 2012. Honors and Fellowships: Sloan Scholar, Stanford University, 1968-1972; Phi Beta Kappa, 1972; IREX/Fulbright-Hays Fellow, 1975-1976; Maybelle MacLeod Lewis Fellow, 1977; IREX/Fulbright-Hays Fellow, 1986; National Endowment for the Humanities, Translation Grant, 1989 – 1990; Marc Raeff Prize for Best Book in 2016, from Eighteenth-Century Russian Studies Association. Major Publications: Books: Monographs 1. Politics of the Russian Nobility 1881-1905, Rutgers University Press, Spring 1984. 299 pp. 2. Boris Chicherin and Early Russian Liberalism, 1828 - 1866, Stanford University Press, Fall 1992. -

Russians Abroad-Gotovo.Indd

Russians abRoad Literary and Cultural Politics of diaspora (1919-1939) The Real Twentieth Century Series Editor – Thomas Seifrid (University of Southern California) Russians abRoad Literary and Cultural Politics of diaspora (1919-1939) GReta n. sLobin edited by Katerina Clark, nancy Condee, dan slobin, and Mark slobin Boston 2013 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: The bibliographic data for this title is available from the Library of Congress. Copyright © 2013 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved ISBN 978-1-61811-214-9 (cloth) ISBN 978-1-61811-215-6 (electronic) Cover illustration by A. Remizov from "Teatr," Center for Russian Culture, Amherst College. Cover design by Ivan Grave. Published by Academic Studies Press in 2013. 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com Effective December 12th, 2017, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. The open access publication of this volume is made possible by: This open access publication is part of a project supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book initiative, which includes the open access release of several Academic Studies Press volumes. To view more titles available as free ebooks and to learn more about this project, please visit borderlinesfoundation.org/open. Published by Academic Studies Press 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com Table of Contents Foreword by Galin Tihanov ....................................... -

Writing a New Self and Creating a Sense for Emotional Belonging: the Case of Nadezhda Teffi, a Russian Writer in Interwar Paris

Writing A New Self and Creating a Sense for Emotional Belonging: The Case of Nadezhda Teffi, a Russian Writer in Interwar Paris Natalia Starostina, Young Harris College When considering the great upheavals of twentieth-century European history, the experience of Russian émigrés in interwar France may strike the historian as a dramatic, sudden, and deep change in luck.1 Many Russian émigrés who ended up on the shores of the Seine after 1917 were the members of the Russian intellectual and political elites who had enjoyed the life of prestige, wealth, refined social and cultural opportunities in tsarist Russia. For many Russian émigrés, life as they knew it was turned upside down when they left Russia. They had to begin their life anew, to rebuild their identities, and to reinvent the self. The experience of women émigrés was especially difficult. Many women had lost their relatives and husbands during the First World War and the Russian Civil War, and many needed to 1 Héléne Menegaldo, Les Russes à Paris: 1919-1939 (Paris: Autrement, 1998) and “L’émigré russe en ses divers avatars,” in Figures de l’émigré russe en France au XIXe et XXe siècle. Fiction et réalité, eds. Charlotte Krauss and Tatiana Victoroff (Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, 2012), 55-84; Nikita Struve, Soixante-dix ans d'émigration russe: 1919-1989 (Paris: Fayard, 1996) and “Les trois vagues de l’émigration russe” in Figures de l’émigré russe en France au XIXe et XXe siècle, op. cit., 23-7; Catherine Klein-Gousseff, L'exil russe: la fabrique du refugié ́ apatride, 1920-1939 (Paris: CNRS, 2008); Robert Harold Johnston, New Mecca, New Babylon: Paris and the Russian Exiles, 1920-1945 (Kingston: McGill Queen's University Press, 1988); Katherine Foshko, “France's Russian Moment: Russian emigré ́s in interwar Paris and French society,” (PhD diss., Yale University, 2008); Marc Raeff, Russia Abroad: A Cultural History of the Russian Emigration, 1919-1939 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), and John Glad, Russia Abroad: Writers, History, Politics (Tenafly, NJ: Hermitage & Birchbark Press, 1999). -

Marc Raeff Columbia University a New Field in Russian Studies Is

quire unjustified self-sufficiency and importance. In the process the relationship existing between party events and the broader backdrop against which they took place gets total- ly lost. Nor are the general socio-political developments and cultural trends in Russia at the time judged in their historical context, but rather in terms of their ultimate effect on party circumstances or on the events of "1917 and all that." Paradoxically, Mr. Hilder- meier is being too historicist in that he makes his own the skewed vision and partisan perspective of his "heroes," while at the same time passing unhistorical judgments in terms of what happened in 1917. Thus he speaks of "illegal" acts and coup d'etat on the part of the tsarist government and yet translates arkhichernosotennyi by archifaschistisch! (p. 176). In his introduction Mr. Hildermeier faults Radkey for writing the history of the PSR in 1917-21 from the perspective of its leading personalities and the accidents of individ- ual actions. But he himself falls into the same trap, for, perforce, he has to concentrate on the leadership (i.e., the intelligentsia), so that the events he deals with acquire also a similar character of chance and unpredictability. He condemns the PSR for failing to understand the underlying dynamics of Russia's modernization and for tackling it in er- roneous manner (i.e., ineffectually from the perspective of 1917). But he admits that these underlying dynamics may be still a matter of debate. Furthermore, such a perspec- tive cannot, by definition, provide the explanation of what are, by his own admission, the actions and thoughts of a dedicated revolutionary intelligentsia bound by its own self- defined mental framework and barely in touch with reality, Mr. -

Political Ideas and Institutions in Imperial Russia

Political Ideas and Institutions in Imperial Russia POLITICAL IDEAS AND INSTITUTIONS IN IMPERIAL RUSSIA Marc Raeff First published 1994 by Westview Press, Inc. Published 2019 by Routledge 52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Copyright © 1994 Taylor & Francis All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Radl~ Marc. Political ideas and institutions in imperial Russia / Marc Raeff p. cm. Includes bibliographical rderences. ISBN 0-8133-1878-5 1. Russia-Politics and government-1689-1801. 2. Russia- Politics and government-1801-1917. I. Title. DK127.R25 1994 947-dc20 93-48ll7 CIP ISBN 13: 978-0-367-28344-5 (hbk) To Edward Kasinec and his fellow librarians, whose enthusiasm and dedication make scholarship not only possible but exciting Contents Acknowledgments List of Credits Introduction 1 ONE Russia After the Emancipation: Views of a Gentleman-Farmer 7 1WO A Reactionary Liberal: M. N. Katkov 22 THREE Some Reflections on Russian Liberalism -

Eighteenth-‐Century Europe Seminar

Eighteenth-Century Europe Seminar Seminar: #417 MEETINGS (1962-1963) Chair: Professor James L. Clifford Co-chair: Professor Peter Gay Secretary: Ms. Beverley Jean Rahn OCT 17 Nomination and unanimous election of professors James L. Clifford and Peter Gay as chair and co-chair respectively. The members nominated Ms. Rahn as secretary. Agreement on the year’s schedule, discussion of the number of members, eighteenth-century sub-fields represented, dinner menu pricing, and general proceedings of the Seminar. NOV 28 The Enlightenment Peter Gay DEC 19 Discussion of Prof. Peter Gay’s The Enlightenment; discussion of procedures to elect new members, to invite guests, and announcement of upcoming talk. JAN 16 Unitarianism: A Middle Class Enlightenment? Robert K. Webb, Professor of History, Columbia University FEB 20 The Impact of the Enlightenment on Eighteenth-Century Music Paul Henry Lang, Professor of Musicology, Columbia University MAR 20 The Concept of Rational Love, Or the Ideology of Mate Selection among the Aristocracy in the 18th Century J. Jean Hecht, Professor of History, Columbia University APR 17 Art and the Enlightenment Rudolph Wittkower, Professor of Art History and Archeology; Mr. Franklin M. Biebel, The Frick Collection MAY 15 Buffon, the Scientist with a Mask Otis Fellows, Professor of French and Romance Philology, Columbia University 1 Eighteenth-Century Europe Seminar Seminar: #417 MEETINGS (1963-1964) Chair: Professor James L. Clifford Co-chair: Professor J. Jean Hecht Secretary: Mrs. Anne Betty Weinshenker OCT 16 Members unanimously elected Mrs. Anne Betty Weinshenker as secretary. Agreement on the year’s schedule, discussion of recruitment of new members and guests in underrepresented eighteenth-century sub-fields. -

Redefining Russian Literary Diaspora, 1920–2020 FRINGE

‘Exile or diaspora? Russians or russophones? Hyphenated or post-colonial? This fascinating 1920-2020 , volume gathers together top specialists to discuss the critical questions that have emerged in Russian literary studies. It will prove to be foundational for the study of the new, de-centered Russian literature of the twenty-fi rst century.’ – J. Douglas Clayton, University of Ottawa ‘The consistently stimulating and erudite chapters enter into fruitful dialogue with contemporary theories of diaspora and globalization, indicating both points of concurrence as well as ways that the Russian experience diverges. An excellent and necessary book.’ – Edythe Haber, Harvard University , ‘Ranging across geographies and genres, a constellation of the world’s leading scholars of Russian culture rethink the nature of the canon, challenge durable myths and archetypes, and upend 1920-2020 previously hierarchical relationships between supposed centres and peripheries.’ – Philip Ross Bullock, University of Oxford Over the century that has passed since the start of the massive post-revolutionary exodus, Russian literature has thrived in multiple locations around the globe. What happens to cultural vocabularies, politics of identity, literary canon and language when writers transcend the metropolitan boundaries and begin to negotiate new experience gained in the process of migration? Redefi ning Russian Literary Diaspora, 1920-2020 sets a new agenda for the study of Russian diaspora writing, countering its conventional reception as a subsidiary branch of national literature and reorienting the fi eld from an emphasis on the origins to an analysis of transnational circulations that shape extraterritorial cultural practices. Integrating various conceptual perspectives, ranging from diaspora and postcolonial studies to the theories of (self-)translation, World Literature and evolutionary literary criticism, the contributors argue for a distinct nature of diasporic literary expression predicated on hybridity, ambivalence and a sense of multiple belonging. -

1 the Pleiade: Five Scholars Who Founded Russian Historical Studies

The Pleiade: Five Scholars Who Founded Russian Historical Studies in America1 There never was a more brilliant cohort of Russian historians in the English-speaking world, nor will there ever likely be again. Five extraordinary students in Michael Karpovich’s seminars of 1946–1947 at Harvard University went on to dominate the Russian historical field in America for some four decades.2 They took the lead at the three preeminent centers of Russian historical study in postwar America—Martin Malia and Nicholas Riasanovsky at Berkeley, Leopold Haimson and Marc Raeff at Columbia, and Richard Pipes at Harvard. At these institutions, they collectively trained the overwhelming majority of prominent Russian historians and between them much of the broader field. They also opened or creatively developed many fields and periods of Russian historical inquiry—more than any other cohort then or since. This study is deeply personal. At Harvard in the late 1980s and early 1990s, my graduate- student colleagues and I often debated who were the “most important” historians of Russia. Our lists usually included all five. After I finished my PhD in 1992, I frequently exchanged letters with Pipes, an exemplary correspondent. The Pleiade continued to fascinate me, the term suggesting itself quite naturally: Terrence Emmons around the same time referred to the cohort as “a remarkable pleiad.”3 In a diary entry I penned on June 9, 1995, I had already laid out the basic premise of this study. “In the field of Russian history in America,” I wrote, 1 I am grateful to the editors of Kritika, and especially Willard Sunderland, as well as Jonathan Beecher, for their careful reading of the overlong manuscript and insightful suggestions. -

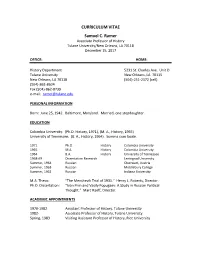

CURRICULUM VITAE Samuel C. Ramer

CURRICULUM VITAE Samuel C. Ramer Associate Professor of History Tulane University/New Orleans, LA 70118 December 15, 2017 OFFICE: HOME: History Department 5231 St. Charles Ave. Unit D Tulane University New Orleans, LA 70115 New Orleans, LA 70118 (504)-251-2372 (cell) (504)-862-8604 Fax (504)-862-8739 e-mail: [email protected] PERSONAL INFORMATION Born: June 25, 1942. Baltimore, Maryland. Married, one stepdaughter. EDUCATION Columbia University: (Ph.D. History, 1971), (M. A., History, 1965) University of Tennessee: (B. A., History, 1964). Summa cum laude. 1971 Ph.D. History Columbia University 1965 M.A. History Columbia University 1964 B.A. History University of Tennessee 1968-69 Dissertation Research Leningrad University Summer, 1964 Russian Oberwart, Austria Summer, 1963 Russian Middlebury College Summer, 1962 Russian Indiana University M.A. Thesis: “The Menshevik Trial of 1931.” Henry L. Roberts, Director. Ph.D. Dissertation: “Ivan Pnin and Vasily Popugaev: A Study in Russian Political Thought.” Marc Raeff, Director. ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 1970-1982 Assistant Professor of History, Tulane University 1982- Associate Professor of History, Tulane University Spring, 1983 Visiting Assistant Professor of History, Rice University Samuel C. Ramer: Resumé 2 GRANTS AND FELLOWSHIPS July, 2005 Director, Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities Teacher Institute for Advanced Study “Poetry and Power: The Genius of Alexander Pushkin” July 5-28, 2005 2004 Eva-Lou Joffrion Edwards grant from Newcomb College to develop course entitled “The History of the Jews in Russia, 1772- 2000.” 1998-1999 International Research and Exchanges Board Grant for The Guidebook Development Project for the National Pushkin Museum Library in St. Petersburg, Russia 1994-1998 Continuation of DOE grant establishing collaborative research with the Institute of Radioecological Problems in Minsk, Belarus. -

INMEMORIAM Leopold H. Haimson, 1927-2010

INMEMORIAM Leopold H. Haimson, 1927-2010 Leopold Haimson, professor emeritus of history at Columbia University, died at his home in New York City on 18 December 2010; he was 83 years old. A leading historian of late imperial and early Soviet history, Haimson shaped the field as a scholar, as a mentor to several generations of graduate students, and as a pioneer in collaborative scholarship with historians from Europe, Russia, and North America. In 2009 the American Associa tion for the Advancement of Slavic Studies (AAASS) recognized these contributions with their award for Distinguished Contributions to Slavic Studies. Haimson was born in Brussels in 1927, the son of Russian emigres who had settled in Belgium after die revolution. In 1940, the family fled the Nazi invasion by fishing boat to Normandy, a voyage that brought them dangerously near to the Allied evacuation at Dunkirk; they ultimately found refuge in the United States. In 1943, Haimson gained ad mission to Harvard University, having lied about his age, as he later admitted. He came late to the study of Russian history, abandoning an earlier interest in the French Revolution. Impressed by the role of the Red Army in the defeat of Nazi Germany, Haimson began studying Russian in 1945 and embarked on his graduate training at Harvard in 1946 as a member of the famous "Karpovich seminar." At Harvard, Haimson studied with a now legendary cohort of fellow Russianists that included Richard Pipes, Martin Malia, and Marc Raeff, later his Columbia colleague. How ever, he spent most of his graduate years in New York, where he worked with die anthro pologist Margaret Mead on a project investigating Soviet political culture.