Volume 1 an EXPLORATORY STUDY of DEVELOPMENTAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessment of Confabulation in Patients RENSON Publishedonline11sepetember2015 GREEN

King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1080/13854046.2015.1084377 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Renson, Y. C. M., Oosterman, J. M., van Damme, J. E., Griekspoor, S. I. A., Wester, A. J., Kopelman, M. D., & Kessels, R. P. C. (2015). Assessment of Confabulation in Patients with Alcohol-Related Cognitive Disorders: The Nijmegen–Venray Confabulation List (NVCL-20). The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 29, 804-823. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2015.1084377 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Psychogenic and Organic Amnesia. a Multidimensional Assessment of Clinical, Neuroradiological, Neuropsychological and Psychopathological Features

Behavioural Neurology 18 (2007) 53–64 53 IOS Press Psychogenic and organic amnesia. A multidimensional assessment of clinical, neuroradiological, neuropsychological and psychopathological features Laura Serraa,∗, Lucia Faddaa,b, Ivana Buccionea, Carlo Caltagironea,b and Giovanni A. Carlesimoa,b aFondazione IRCCS Santa Lucia, Roma, Italy bClinica Neurologica, Universita` Tor Vergata, Roma, Italy Abstract. Psychogenic amnesia is a complex disorder characterised by a wide variety of symptoms. Consequently, in a number of cases it is difficult distinguish it from organic memory impairment. The present study reports a new case of global psychogenic amnesia compared with two patients with amnesia underlain by organic brain damage. Our aim was to identify features useful for distinguishing between psychogenic and organic forms of memory impairment. The findings show the usefulness of a multidimensional evaluation of clinical, neuroradiological, neuropsychological and psychopathological aspects, to provide convergent findings useful for differentiating the two forms of memory disorder. Keywords: Amnesia, psychogenic origin, organic origin 1. Introduction ness of the self – and a period of wandering. According to Kopelman [33], there are three main predisposing Psychogenic or dissociative amnesia (DSM-IV- factors for global psychogenic amnesia: i) a history of TR) [1] is a clinical syndrome characterised by a mem- transient, organic amnesia due to epilepsy [52], head ory disorder of nonorganic origin. Following Kopel- injury [4] or alcoholic blackouts [20]; ii) a history of man [31,33], psychogenic amnesia can either be sit- psychiatric disorders such as depressed mood, and iii) uation specific or global. Situation specific amnesia a severe precipitating stress, such as marital or emo- refers to memory loss for a particular incident or part tional discord [23], bereavement [49], financial prob- of an incident and can arise in a variety of circum- lems [23] or war [21,48]. -

What Is It Like to Be Confabulating?

What is it like to be Confabulating? Sahba Besharati, Aikaterini Fotopoulou and Michael D. Kopelman Kings College London, Institute of Psychiatry, London UK Different kinds of confabulations may arise in neurological and psychiatric disorders. This chapter first offers conceptual distinctions between spontaneous and momentary (“provoked”) confabulations, as well as between these types of confabulation and other kinds of false memories. The chapter then reviews current explanatory theories, emphasizing that both neurocognitive and motivational factors account for the content of confabulations. We place particular emphasis on a general model of confabulation that considers cognitive dysfunctions in memory and executive functioning in parallel with social and emotional factors. It is argued that all these dimensions need to be taken into account for a phenomenologically rich description of confabulation. The role of the motivated content of confabulation and the subjective experience of the patient are particularly relevant in effective management and rehabilitation strategies. Finally, we discuss a case example in order to illustrate how seemingly meaningless false memories are actually meaningful if placed in the context of the patient’s own perspective and autobiographical memory. Key words: Confabulation; False memory; Motivation; Self; Rehabilitation. 1 Memory is often subject to errors of omission and commission such that recollection includes instances of forgetting, or distorting past experience. The study of pathological forms of exaggerated memory distortion has provided useful insights into the mechanisms of normal reconstructive remembering (Johnson, 1991; Kopelman, 1999; Schacter, Norman & Kotstall, 1998). An extreme form of pathological memory distortion is confabulation. Different variants of confabulation are found to arise in neurological and psychiatric disorders. -

Functional–Anatomic Correlates of Control Processes in Memory

The Journal of Neuroscience, May 15, 2003 • 23(10):3999–4004 • 3999 Functional–Anatomic Correlates of Control Processes in Memory Randy L. Buckner Department of Psychology, Howard Hughes Medical Institute at Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri 63130 Introduction when memory retrieval requires flexible use of control processes A central role for control processes in long-term memory is ap- (Milner et al., 1985; Schacter, 1987; Shimmamura et al., 1991). In parent when one considers that there is far more information many cases, patients will fail to recall, or sometimes even recog- available in memory than can be accessed at any single moment nize, information (for review, see Wheeler et al., 1995) or inap- (Tulving and Pearlstone, 1966; Koriat, 2000). Much as selective propriately estimate the source or timing, or both, of a past epi- attention operates to focus processing on objects in the environ- sode (for review, see Schacter, 1987). In rare cases, a patient may ment, related control processes are required to constrain and make up episodes from the past while believing they really hap- select from information stored in memory. pened, a phenomenon called “confabulation” (Moscovitch, Neuroimaging studies have expanded our understanding of 1989; Burgess and Shallice, 1996). Unlike purer forms of amnesia, control processes in long-term memory in three important ways. which result from medial temporal and diencephalic lesions First, networks of regions, prominently including specific regions (Scoville and Milner, 1957; Squire, 1992; Cohen and Eichen- in prefrontal cortex, contribute to control processes during baum, 1993), the deficits after frontal damage align more to im- memory retrieval. -

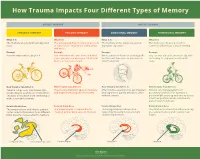

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory EXPLICIT MEMORY IMPLICIT MEMORY SEMANTIC MEMORY EPISODIC MEMORY EMOTIONAL MEMORY PROCEDURAL MEMORY What It Is What It Is What It Is What It Is The memory of general knowledge and The autobiographical memory of an event The memory of the emotions you felt The memory of how to perform a facts. or experience – including the who, what, during an experience. common task without actively thinking and where. Example Example Example Example You remember what a bicycle is. You remember who was there and what When a wave of shame or anxiety grabs You can ride a bicycle automatically, with- street you were on when you fell off your you the next time you see your bicycle out having to stop and recall how it’s bicycle in front of a crowd. after the big fall. done. How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It Trauma can prevent information (like Trauma can shutdown episodic memory After trauma, a person may get triggered Trauma can change patterns of words, images, sounds, etc.) from differ- and fragment the sequence of events. and experience painful emotions, often procedural memory. For example, a ent parts of the brain from combining to without context. person might tense up and unconsciously make a semantic memory. alter their posture, which could lead to pain or even numbness. Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area The temporal lobe and inferior parietal The hippocampus is responsible for The amygdala plays a key role in The striatum is associated with producing cortex collect information from different creating and recalling episodic memory. -

Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1994 Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders. Shannon Buckles Sebastian Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Sebastian, Shannon Buckles, "Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders." (1994). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 5826. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/5826 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Memory and Narrative: Reading the Things They Carried for Psyche and Persona Frank Hassebrock and Brenda Boyle, Denison University

Memory and Narrative: Reading The Things They Carried for Psyche and Persona Frank Hassebrock and Brenda Boyle, Denison University Abstract: This essay looks closely at how two disciplines, Psychology and English, can use the same text for similar purposes. A Psychology professor discusses how Tim O'Brien's The Things They Carried can exemplify for his students how memory is used to construct a self, a psyche. A teacher of literature then examines how the same text demonstrates for students the rhetorical construction of a fictional self, a persona, and also how that construction is influenced by the various historical periods represented in the novel's stories. Through the investigation of these two disciplinary approaches, students in our classes gain an appreciation for the psychological functions of remembering and the rhetorical functions of reading. People select and interpret certain memories as self-defining, providing them with privileged status in the life story… . To a certain degree, then, identity is a product of choice. We choose the events we consider most important for defining who we are and providing our lives with some semblance of unity and purpose. And we endow them with symbolism, lessons learned, integrative themes, and other personal meaning that make sense to us in the present as we survey the past and anticipate the future. (McAdams, 2004, p. 104) A rhetoric incorporates more than practical strategies for speaking and writing. Rhetoric reflects the values and perspectives of a culture. It is a distillation of what a given society counts as knowledge and evidence, how it defines social connections and responsibilities, the context in which communicative acts will be interpreted. -

Metamemory and Memory Discrepancies in Directed Forgetting of Emotional Information

Research Reports Metamemory and Memory Discrepancies in Directed Forgetting of Emotional Information Dicle Çapan a, Simay Ikier b [a] Department of Psychology, Koç University, Istanbul, Turkey. [b] Department of Psychology, Bahçeşehir University, Istanbul, Turkey. Europe's Journal of Psychology, 2021, Vol. 17(1), 44–52, https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.2567 Received: 2019-12-17 • Accepted: 2020-04-23 • Published (VoR): 2021-02-26 Handling Editor: Rhian Worth, University of South Wales, Pontypridd, United Kingdom Corresponding Author: Dicle Çapan, Koç University, Rumelifeneri Mahallesi, Sarıyer Rumeli Feneri Yolu, 34450 Sarıyer Istanbul, Turkey. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Directed Forgetting (DF) studies show that it is possible to exert cognitive control to intentionally forget information. The aim of the present study was to investigate how aware individuals are of the control they have over what they remember and forget when the information is emotional. Participants were presented with positive, negative and neutral photographs, and each photograph was followed by either a Remember or a Forget instruction. Then, for each photograph, participants provided Judgments of Learning (JOLs) by indicating their likelihood of recognizing that item on a subsequent test. In the recognition phase, participants were asked to indicate all old items, irrespective of instruction. Remember items had higher JOLs than Forget items for all item types, indicating that participants believe they can intentionally forget even emotional information—which is not the case based on the actual recognition results. DF effect, which was calculated by subtracting recognition for Forget items from Remember ones was only significant for neutral items. Emotional information disrupted cognitive control, eliminating the DF effect. -

Development and Validation of a Parent Measure of Socialization of Truth and Lie-Telling Behavior', Applied Developmental Science

Edinburgh Research Explorer Socialization of lying scale Citation for published version: Talwar, V, Lavoie, J & Crossman, AM 2021, 'Socialization of lying scale: Development and validation of a parent measure of socialization of truth and lie-telling behavior', Applied Developmental Science. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2021.1927732 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1080/10888691.2021.1927732 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Applied Developmental Science General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 06. Oct. 2021 Applied Developmental Science ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/hads20 Socialization of lying scale: development and validation of a parent measure of socialization of truth and lie-telling behavior Victoria Talwar, Jennifer Lavoie & Angela M. Crossman To cite this article: Victoria Talwar, Jennifer Lavoie & Angela M. Crossman (2021): Socialization of lying scale: development and validation of a parent measure of socialization of truth and lie-telling behavior, Applied Developmental Science, DOI: 10.1080/10888691.2021.1927732 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2021.1927732 © 2021 The Author(s). -

Introduction: Karmiloff-Smith from Piaget to Neuroconstructivisim a History of Ideas

Thinking Developmentally from Constructivism to Neuroconstructivism Introduction: Karmiloff-Smith from Piaget to neuroconstructivisim A history of ideas Michael S. C. Thomas Developmental Neurocognition Lab, Centre for Brain and Cognitive Development, Department of Psychological Sciences, Birkbeck, University of London Mark H. Johnson Department of Psychology, University of Cambridge, and Centre for Brain & Cognitive Development, Birkbeck, University of London Introduction Annette Karmiloff-Smith was a seminal thinker in the field of child development in a career spanning more than 45 years. She was the recipient of many awards, including the European Science Foundation Latsis Prize for Cognitive Sciences (the first woman to be awarded this prize), Fellowships of the British Academy, the Cognitive Science Society, the Academy of Medical Sciences, and the Royal Society of Arts, as well as honorary doctorates from universities across the world. She was awarded a CBE for services to cognitive development in the 2004 Queen’s Birthday Honours list. Annette passed away in December 2016, but she had already selected a set of papers that charted the evolution of her ideas, which are collected in this volume. At the time of her death, Annette was engaged in an innovative research project studying development and ageing in Down syndrome (DS) as a model to study the causes of Alzheimer’s disease. This multidisciplinary project, advanced by the LonDownS consortium, brought together experts in cognitive development, psychiatry, brain imaging, genetics, cellular biology, and mouse modelling. Annette’s focus in this project was to explore early development in infants and toddlers with Down syndrome. How could this inform Alzheimer’s disease? The logic is a mark of Annette’s brilliant theoretical insight. -

ELA/Literacy Released Item 2018 Grade 11 Research Simulation

ELA/Literacy Released Item 2018 Grade 11 Research Simulation Task Factors Interfering With Memory Accuracy II428729783 © 2019 CCSSO, LLC English Language Arts/Literacy Today you will research scientific discoveries about how memory works. You will read the article “New Discoveries on Optimizing Memory Formation.” Then you will read the passage from “Tricks of Memory” and the article “Exceptional Memory Explained: How Some People Remember What They Had for Lunch 20 Years Ago.” As you review these sources, you will gather and synthesize information and answer questions about scientific concepts so you can write an analytical essay. Read the article “New Discoveries on Optimizing Memory Formation.” Then answer the questions. New Discoveries on Optimizing Memory Formation by William R. Klemm 1 As each of us goes through life, we remember a little and forget a lot. The stockpile of what we remember contributes greatly to define us and our place in the world. Thus, it is important to remember and optimize the processes that make that possible. 2 People who compete in memory contests (“memory athletes”) have long known the value of associational cues (see my Memory Power 101 book). Neuroscientists have known for a long time about memory consolidation (converting short-term memory to long-term form) and the value of associational cues. But now, important new understanding is arising from a research lab at Northwestern that links cueing to “re-consolidation” and reveals new possibilities for optimizing long-term memory formation. 3 The underlying research approach is based on such well-established memory principles as: 1. When information is first acquired, it is tagged for its potential importance or value. -

Effect of the Time-Of-Day of Training on Explicit Memory

Time-of-dayBrazilian Journal of training of Medical and memory and Biological Research (2008) 41: 477-481 477 ISSN 0100-879X Effect of the time-of-day of training on explicit memory F.F. Barbosa and F.S. Albuquerque Departamento de Fisiologia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, RN, Brasil Correspondence to: F.F. Barbosa, Departamento de Fisiologia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Lagoa Nova, Caixa Postal 1511, 59072-970 Natal, RN, Brasil Fax: +55-84-211-9206. E-mail: [email protected] Studies have shown a time-of-day of training effect on long-term explicit memory with a greater effect being shown in the afternoon than in the morning. However, these studies did not control the chronotype variable. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to assess if the time-of-day effect on explicit memory would continue if this variable were controlled, in addition to identifying the occurrence of a possible synchronic effect. A total of 68 undergraduates were classified as morning, intermediate, or afternoon types. The subjects listened to a list of 10 words during the training phase and immediately performed a recognition task, a procedure which they repeated twice. One week later, they underwent an unannounced recognition test. The target list and the distractor words were the same in all series. The subjects were allocated to two groups according to acquisition time: a morning group (N = 32), and an afternoon group (N = 36). One week later, some of the subjects in each of these groups were subjected to a test in the morning (N = 35) or in the afternoon (N = 33).