The Theory and Practice of Nature: Reinventing Nature Through the Literature of Jim Harrison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conor Mcpherson 88 Min., 1.85:1, 35Mm

Mongrel Media Presents THE ECLIPSE A film by Conor McPherson 88 min., 1.85:1, 35mm (88min., Ireland, 2009) www.theeclipsefilm.com Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith 1028 Queen Street West Star PR Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Tel: 416-488-4436 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html SYNOPSIS THE ECLIPSE tells the story of Michael Farr (Ciarán Hinds), a teacher raising his two kids alone since his wife died two years earlier. Lately he has been seeing and hearing strange things late at night in his house. He isn't sure if he is simply having terrifying nightmares or if his house is haunted. Each year, the seaside town where Michael lives hosts an international literary festival, attracting writers from all over the world. Michael works as a volunteer for the festival and is assigned the attractive Lena Morelle (Iben Hjejle), an author of books about ghosts and the supernatural, to look after. They become friendly and he eagerly tells her of his experiences. For the first time he has met someone who can accept the reality of what has been happening to him. However, Lena’s attention is pulled elsewhere. She has come to the festival at the bidding of world-renowned novelist Nicholas Holden (Aidan Quinn), with whom she had a brief affair the previous year. He has fallen in love with Lena and is going through a turbulent time, eager to leave his wife to be with her. -

Director Zwick Defies the Typical WWII Film Advertisement by Anthony Breznican, USA TODAY

Director Zwick defies the typical WWII ... EC Be one of the first 100 businesses to register and have $50 loaded onto your debit card. BUSINESS nroll now 1 Use promo code BAI208MMNG ADVA TAG (!@ PRINTTHIS Powered by r;a· tility I ~ Click to Print I SAVE n-ilS I EM<\ IL niS I Oose Director Zwick defies the typical WWII film Advertisement By Anthony Breznican, USA TODAY LOS ANGELES- It all started with little boys playing war. REVIEW: War drama 'Defiance' meets with resistance In the late 1950s, Edward Zwick was a little boy running around his suburban Chicago neighborhood with friends, pretending to fight the Axis powers like the heroic soldiers or flying aces from their fa write World War II movies. "Gregory Peck seemed to star in all of them -12 O'Clock High, The Guns ofNavarone," says Zwick, now 56, who grew up to become the director of Glory, Legends of the Fall, The Last Samurai and Blood Diamond. "But," he adds, ·~o be a Jewish kid was to hear other stories ... " Those were about the Holocaust, and ZWick was secretly troubled by the all-too-easy question kids often ask, which has a million hard answers: \lllhydidn~theyfight back? ''You try to reconcile the difference between the stories ~u heard aboutthe victimization of people like you, and then these other heroes," he says of the screen fighters he idolized. "It had some kind of pain attached to it, really." He has finally gotten to tell his own story of tough, fighting Jews, and he did it with the help of007. -

Brad Pitt from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Brad Pitt From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia For the Australian boxer, see Brad Pitt (boxer). Brad Pitt Pitt at Sydney's red carpet for World War Zpremiere in 2013 Born William Bradley Pitt December 18, 1963 (age 50) Shawnee, Oklahoma, U.S. Occupation Actor, film producer Years active 1987–present Religion None Spouse(s) Jennifer Aniston (m. 2000–05) Partner(s) Angelina Jolie (2005–present; engaged) Children 6 William Bradley "Brad" Pitt (born December 18, 1963) is an American actor and film producer. He has received a Golden Globe Award, a Screen Actors Guild Award, and three Academy Award nominations in acting categories, and received two further Academy Award nominations, winning one, for productions of his film production company Plan B Entertainment. He has been described as one of the world's most attractive men, a label for which he has received substantial media attention.[1][2] Pitt first gained recognition as a cowboy hitchhiker in the road movie Thelma & Louise (1991). His first leading roles in big-budget productions came with A River Runs Through It (1992), Interview with the Vampire (1994), and Legends of the Fall (1994). He gave critically acclaimed performances in the crime thriller Seven and the science fiction film 12 Monkeys (both 1995), the latter earning him a Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actor and an Academy Award nomination. Pitt starred in the cult filmFight Club (1999) and the major international hit Ocean's Eleven (2001) and its sequels, Ocean's Twelve (2004) and Ocean's Thirteen (2007). His greatest commercial successes have been Troy (2004), Mr. -

On the Square in Oxford Since 1979. U.S

Dear READER, Service and Gratitude It is not possible to express sufficiently how thankful we at Square Books have been, and remain, for the amazing support so many of you have shown to this bookstore—for forty years, but especially now. Nor can I adequately thank the loyal, smart, devoted booksellers here who have helped us take safe steps through this unprecedented difficulty, and continue to do so, until we find our way to the other side. All have shown strength, resourcefulness, resilience, and skill that maybe even they themselves did not know they possessed. We are hearing stories from many of our far-flung independent bookstore cohorts as well as other local businesses, where, in this community, there has long been—before Amazon, before Sears—a shared knowledge regarding the importance of supporting local places and local people. My mother made it very clear to me in my early teens why we shopped at Mr. Levy’s Jitney Jungle—where Paul James, Patty Lampkin, Richard Miller, Wall Doxey, and Alice Blinder all worked. Square Books is where Slade Lewis, Sid Albritton, Andrew Pearcy, Jesse Bassett, Jill Moore, Dani Buckingham, Paul Fyke, Jude Burke-Lewis, Lyn Roberts, Turner Byrd, Lisa Howorth, Sami Thomason, Bill Cusumano, Cody Morrison, Andrew Frieman, Katelyn O’Brien, Beckett Howorth, Cam Hudson, Morgan McComb, Molly Neff, Ted O’Brien, Gunnar Ohberg, Kathy Neff, Al Morse, Rachel Tibbs, Camille White, Sasha Tropp, Zeke Yarbrough, and I all work. And Square Books is where I hope we all continue to work when we’ve found our path home-free. -

Human' Jaspects of Aaonsí F*Oshv ÍK\ Tke Pilrns Ana /Movéis ÍK\ É^ of the 1980S and 1990S

DOCTORAL Sara MarHn .Alegre -Human than "Human' jAspects of AAonsí F*osHv ÍK\ tke Pilrns ana /Movéis ÍK\ é^ of the 1980s and 1990s Dirigida per: Dr. Departement de Pilologia jA^glesa i de oermanisfica/ T-acwIfat de Uetres/ AUTÓNOMA D^ BARCELONA/ Bellaterra, 1990. - Aldiss, Brian. BilBon Year Spree. London: Corgi, 1973. - Aldridge, Alexandra. 77» Scientific World View in Dystopia. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press, 1978 (1984). - Alexander, Garth. "Hollywood Dream Turns to Nightmare for Sony", in 77» Sunday Times, 20 November 1994, section 2 Business: 7. - Amis, Martin. 77» Moronic Inferno (1986). HarmorKlsworth: Penguin, 1987. - Andrews, Nigel. "Nightmares and Nasties" in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the MecBa. London and Sydney: Ruto Press, 1984:39 - 47. - Ashley, Bob. 77» Study of Popidar Fiction: A Source Book. London: Pinter Publishers, 1989. - Attebery, Brian. Strategies of Fantasy. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1992. - Bahar, Saba. "Monstrosity, Historicity and Frankenstein" in 77» European English Messenger, vol. IV, no. 2, Autumn 1995:12 -15. - Baldick, Chris. In Frankenstein's Shadow: Myth, Monstrosity, and Nineteenth-Century Writing. Oxford: Oxford Clarendon Press, 1987. - Baring, Anne and Cashford, Jutes. 77» Myth of the Goddess: Evolution of an Image (1991). Harmondsworth: Penguin - Arkana, 1993. - Barker, Martin. 'Introduction" to Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Media. London and Sydney: Ruto Press, 1984(a): 1-6. "Nasties': Problems of Identification" in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the MecBa. London and Sydney. Ruto Press, 1984(b): 104 - 118. »Nasty Politics or Video Nasties?' in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Medß. -

Produced with the Participation of Blue Ice Docs

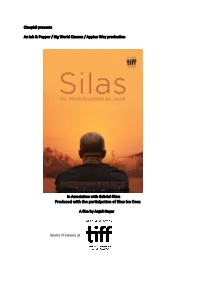

Cinephil presents An Ink & Pepper / Big World Cinema / Appian Way production In Association with Gabriel Films Produced with the participation of Blue Ice Docs A film by Anjali Nayar World Premiere at 80 minutes English, Liberian English • • Canada/South Africa/Kenya 2017 • Contacts at TIFF: Producer: Producer: Steven Markovitz Anjali Nayar Big World Cinema Ink & Pepper Productions E: [email protected] E: T: +27 83 2611 044 T: +1- 415-910-4625 Sales Agent: Publicist: Philippa Kowarsky Charlene Coy Cinephil C2C Communications E: [email protected] E: [email protected] T: +972 3 566 4129 T: +1-416-451-1471 Tagline: No more business as usual Logline With a network of dedicated citizen reporters by his side, seasoned Liberian activist Silas Siakor challenges the corrupt and nepotistic status quo in his fight for local communities. Synopsis Liberian activist, Silas Siakor is a tireless crusader, fighting to crush corruption and environmental destruction in the country he loves. Through the focus on one country, Silas is a global tale that -

Jim Harrison “A Natural History of Some Poems” JIM HARRISON an INTERVIEW by Allen Morris Jones

The sense of play that a poet needs to make language an ally — often thought of as congenital insincerity by the public—provides the at least momentary pleasure of creation; the sense of having a foothold, if not full membership, in a guild as old as man. The child who carves a tombstone or rock out a bar of soap knows some of this pleasure. —Jim Harrison “A Natural History of Some Poems” JIM HARRISON AN INTERVIEW by Allen Morris Jones t’s a weakness and I can’t get rid of it. How I keep wanting to meet the writers I admire. When he’s in Montana, the poet and novelist Jim Harrison does most of his work in a shed behind his refurbished farmhouse. The house Iitself is tastefully done up in arts and crafts, arrangements of hardwoods and mirrors and original art; his writing space, however, could have come from impoverished Mexico, Argentina, the Balkans. Some mountain village still ten years away from electricity. There’s a sleeping cot (quilts piled up in a wad) and a good-sized desk. A corkboard of photos and shelves full of personal totems. Little else. It’s the room of a writer leery of all distraction save memory. On a Saturday morning in early June, he was working in a raveling, wheat- yellow t-shirt and black sweat pants. Belly in his lap and a legal pad on his desk, the pages folded back. “I’ve never used a computer, even a typewriter. I have a problem with electricity.” This was in the Paradise Valley, south of Livingston. -

The Official Magazine of the Location Managers Guild International SPRING 2016

SPRING 2016 The Official Magazine of the Location Managers Guild International FILM AT WE ARE IN THE STUDIO ZONE Variety of backdrops on one versatile campus » 500 acres of private, adaptable film environment » 300,000 square feet of sound stages » 225 acres of open parking lots » 9,000-seat grandstand with grass infield » 5-acre self-sustaining urban farm » 244 all-suite Sheraton Fairplex Hotel, KOA RV Park and equipment rental company all on-site » Flexible and professional staff Contact: Melissa DeMonaco-Tapia at 909.865.4042 or [email protected] SPRING 2016 / IN THIS ISSUE VOLUME 4 / ISSUE 2 4 EDITORS’ DESK 6 LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT 8 32 CONTRIBUTORS STRAIGHT OUTTA LOCATIONS Alison Taylor takes us to Compton Photo courtesy of Alison Taylor/LMGI Alison of courtesy Photo 40 GENTLY SPEAKING Claudia Eastman in Northern 10 England IN THE NEWS • London Focus/LMGI • A City Runs Through It • LAFCN/Bill Bowling 54 • Comic-Con Commandos • PSA That’s No Bull MARTINI SHOT 22 47° 35' 47" N / 120° 39' 55" W • Unintended Consequences CAREER FOCUS Chris Baugh: What’s luck got to do with it? 26 IN MY CITY Matt Palmer explores Calgary 20 AND THE 46 ON THE COVER NOMINEES ARE ... LONG LIVE O’Shea Jackson Jr. on set. Congratulations to the ROCK AND ROLL Photo by Jaimie Trueblood/ nominees and honorees of Mick Ratman faces the Courtesy of Universal the April 23 Awards Show music Pictures LMGI COMPASS | Spring 2016 • 3 FROM THE EDITORS’ DESK What’s in a name? Welcome to the Location Managers Guild International rebrand! We are excited about our continued growth, welcome our new members and join them in cel- ebrating excellence on location worldwide. -

REEL ADVENTURES: Badlands and Bad Guys Calgary to Drumheller, Brooks and Hanna Th E Land, Broken by the Unique Geography of Dinosaur Country, Provides the Perfect

REEL ADVENTURES: Badlands and Bad Guys Calgary to Drumheller, Brooks and Hanna Th e land, broken by the unique geography of dinosaur country, provides the perfect . scenery for the moody (Unforgiven), the dangerous (Texas Rangers) and the rollicking (Knockaround Guys). Th ere’s plenty of Brokeback Mountain here, too, and Th e Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford. Th e Assassination of Jesse James by the 10 Lake Coward Robert Ford (2007) puts Brad Pitt Louise Banff in the lead role in the retelling of the in- Stoney Morley Reserve 1A famous outlaw’s last days, and Casey Canmore Seebe Affl eck in the role of his killer. 1 Brokeback Mountain (2005) tells the poignant story of love between two ranch 1 BassanoBassano hands and of how it aff ects their lives over Siksika Nation 873 544 the years. Jake Gyllenhaal and the late MillicentMillicent Heath Ledger star. Knockaround Guys (2001) is a comedy 873 about the misadventures of sons of mob- km 10 20 30 535 mi sters sent on an errand to a small town. RainierRainier 10 20 Barry Pepper stars with Vin Diesel and Th ere’s an imposing size to the country east of Film Location John Malkovich. Calgary, a swatch of broad plain under a big Texas Rangers (2001) tells the story how Drive-by Film Location sky that needs only the silhouette of horse and Leander McNelly (Dylan McDermott) rider to conjure up images of bold cinematic Photo Opportunity shaped the legendary lawmen from a westerns. So choose your hat colour, black or bunch of post-Civil-War ne’er-do-wells. -

June 14, 2018 the Honorable Bob Goodlatte, Chairman The

June 14, 2018 The Honorable Bob Goodlatte, Chairman The Honorable Jerry Nadler, Ranking Member House Committee on the Judiciary 2138 Rayburn House Office Building Washington, D.C. 20515 The Honorable Greg Walden, Chairman The Honorable Joe Barton, Vice Chairman The Honorable Frank Pallone, Ranking Member House Energy and Commerce Committee 2125 Rayburn House Office Building Washington, D.C. 20515 Dear Chairmen, Vice Chairman, and Ranking Members: We, the undersigned, are creatives who make our living in the entertainment industries. Whether we work in film, television, publishing, music, or photography, we and our colleagues have all been affected by the rampant, illicit activity that occurs on the major internet platforms, including Google and Facebook. There has been growing concern in Washington, in the press, and among Americans about the lack of responsibility exercised by the major internet platforms toward harmful and illegal activity taking place on their services. For decades, online gatekeepers like Facebook and Google have turned a blind eye to the proliferation of widespread societal harms on their platforms. From sex trafficking to foreign influence over our elections, from privacy to piracy, it has become increasingly clear that more needs to be done to ensure platform responsibility. In recent hearings in both the House and the Senate, Facebook’s CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, characterized Silicon Valley’s failure to take an appropriately broad view of its responsibility as a “big mistake.” But whether the lack of responsibility was a “mistake” or something else, the failure of Facebook, Google, and others to take responsibility is rooted in decades-old government policies, including legal immunities and safe harbors, that treat these companies differently than other industries and actually absolve internet platforms of responsibility. -

Download Spring 2017

Grove Press Atlantic Monthly Press Black Cat The Mysterious Press Spring 2017 GROVE ATLANTIC 154 West 14th Street, 12 FL, New York, New York 10011 ATLANTIC MONTHLY PRESS Hardcovers AVAILABLE IN MARCH A collection of essays from “the Henry Miller of food writing” (Wall Street Journal)—beloved New York Times bestselling writer Jim Harrison A Really Big Lunch Meditations on Food and Life from the Roving Gourmand Jim Harrison With an introduction by Mario Batali MARKETING “[A] culinary combo plate of Hunter S. Thompson, Ernest Hemingway, Julian A Really Big Lunch will be published on the Schnabel, and Sam Peckinpah . Harrison writes with enough force to make one-year anniversary of Harrison’s death your knees buckle.” —Jane and Michael Stern, New York Times Book Review on The Raw and the Cooked There was an enormous outpouring of grief and recognition of Harrison’s work at the ew York Times bestselling author Jim Harrison was one of this coun- time of his passing in March 2016 try’s most beloved writers, a muscular, brilliantly economic stylist Harrison’s last book, The Ancient Minstrel, Nwith a salty wisdom. He also wrote some of the best essays on food was a New York Times and national around, earning praise as “the poet laureate of appetite” (Dallas Morning bestseller, as well as an Amazon Editors’ News). A Really Big Lunch, to be published on the one-year anniversary of Best Book of the Month. It garnered strong Harrison’s death, collects many of his food pieces for the first time—and taps reviews from the New York Times Book into his larger-than-life appetite with wit and verve. -

Re-Framing Masculinity in Japan: Tom Cruise, the Last Samurai and the Fluid Metanarratives of History

50 Re-Framing Masculinity in Japan: Tom Cruise, The Last Samurai and the Fluid Metanarratives of History RE-FRAMING MASCULINITY IN JAPAN: TOM CRUISE, THE LAST SAMURAI AND THE FLUID METANARRATIVES OF HISTORY Maria GRAJDIAN1 Abstract After its release in 2003, The Last Samurai became a major success at the Japanese (and international) box-office, simultaneously marking a turning point in the illustration of Japan by Western media, and more specifically, by US-American institutions of mass entertainment, such as Hollywood. The Last Samurai has been mostly discussed on the background of the historical realities it depicts (the Meiji Restoration of 1868, the unconditional import of Western artefacts and values, the clash between old and new in Japan by mid-19th century) or from the perspective of the impact it had on the representation of Asian or other non- European cultures by American mainstream mass-media. Based on a 15-year empiric-phenomenological fieldwork in the slippery domain of Japanese mass-media, as well as in-depth literature research on new media, masculinity studies and entertainment industry with specific focus on Japan, this paper argues that the character embodied by Tom Cruise – the typical white male from Japanese perspective – displayed an unexpectedly refreshing insight into the prevalent masculinity ideal in Japan, as subliminally suggested by the Japanese characters. On the one hand, it challenges the image of the samurai, both in its historical idealization (stoic warriors and social elite) and in their contemporary adaptation (carriers of Japan’s post-war recovery). On the other hand, it questions the values incorporated by classical Japanese masculinity and suggests a credible alternative, with emotional flexibility, human warmth and mental vulnerability as potential core attributes.