Computer Security Sources Ancient Egypt Ancient China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CS 105 Review Questions #2 in Addition to These Questions

1 CS 105 Review Questions #2 In addition to these questions, remember to look over your labs, homework assignments, readings in the book and your notes. 1. Explain how writing functions inside a Python program can potentially make the program more concise (i.e. take up fewer total lines of code). 2. The following Python statement may cause a ZeroDivisionError. Rewrite the code so that the program will not automatically halt if this error occurs. c = a / b 3. Indicate whether each statement is true or false. a. In ASCII code, the values corresponding to letters in the alphabet are consecutive. b. ASCII code uses the same values for lowercase letters as it does for capital letters. c. In ASCII code, non-printing, invisible characters all have value 0 4. Properties of ASCII representation: a. Each character is stored as how much information? b. If the ASCII code for ‘A’ is 65, then the ASCII code for ‘M’ should be ______. c. Suppose that the hexadecimal ASCII code for the lowercase letter ‘a’ is 0x61. Which lowercase letter would have the hexadecimal ASCII code 0x71 ? d. If we represent the sentence “The cat slept.” in ASCII code (not including the quotation marks), how many bytes does this require? e. How does Unicode differ from ASCII? 5. Estimate the size of the following file. It contains a 500-page book, where a typical page has 2000 characters of ASCII text and one indexed-color image measuring 200x300 pixels. “Indexed color” means that each pixel of an image takes up one byte. -

Chapter 3 – Block Ciphers and the Data Encryption Standard

Chapter 3 –Block Ciphers and the Data Cryptography and Network Encryption Standard Security All the afternoon Mungo had been working on Stern's Chapter 3 code, principally with the aid of the latest messages which he had copied down at the Nevin Square drop. Stern was very confident. He must be well aware London Central knew about that drop. It was obvious Fifth Edition that they didn't care how often Mungo read their messages, so confident were they in the by William Stallings impenetrability of the code. —Talking to Strange Men, Ruth Rendell Lecture slides by Lawrie Brown Modern Block Ciphers Block vs Stream Ciphers now look at modern block ciphers • block ciphers process messages in blocks, each one of the most widely used types of of which is then en/decrypted cryptographic algorithms • like a substitution on very big characters provide secrecy /hii/authentication services – 64‐bits or more focus on DES (Data Encryption Standard) • stream ciphers process messages a bit or byte at a time when en/decrypting to illustrate block cipher design principles • many current ciphers are block ciphers – better analysed – broader range of applications Block vs Stream Ciphers Block Cipher Principles • most symmetric block ciphers are based on a Feistel Cipher Structure • needed since must be able to decrypt ciphertext to recover messages efficiently • bloc k cihiphers lklook like an extremely large substitution • would need table of 264 entries for a 64‐bit block • instead create from smaller building blocks • using idea of a product cipher 1 Claude -

COS433/Math 473: Cryptography Mark Zhandry Princeton University Spring 2017 Cryptography Is Everywhere a Long & Rich History

COS433/Math 473: Cryptography Mark Zhandry Princeton University Spring 2017 Cryptography Is Everywhere A Long & Rich History Examples: • ~50 B.C. – Caesar Cipher • 1587 – Babington Plot • WWI – Zimmermann Telegram • WWII – Enigma • 1976/77 – Public Key Cryptography • 1990’s – Widespread adoption on the Internet Increasingly Important COS 433 Practice Theory Inherent to the study of crypto • Working knowledge of fundamentals is crucial • Cannot discern security by experimentation • Proofs, reductions, probability are necessary COS 433 What you should expect to learn: • Foundations and principles of modern cryptography • Core building blocks • Applications Bonus: • Debunking some Hollywood crypto • Better understanding of crypto news COS 433 What you will not learn: • Hacking • Crypto implementations • How to design secure systems • Viruses, worms, buffer overflows, etc Administrivia Course Information Instructor: Mark Zhandry (mzhandry@p) TA: Fermi Ma (fermima1@g) Lectures: MW 1:30-2:50pm Webpage: cs.princeton.edu/~mzhandry/2017-Spring-COS433/ Office Hours: please fill out Doodle poll Piazza piaZZa.com/princeton/spring2017/cos433mat473_s2017 Main channel of communication • Course announcements • Discuss homework problems with other students • Find study groups • Ask content questions to instructors, other students Prerequisites • Ability to read and write mathematical proofs • Familiarity with algorithms, analyZing running time, proving correctness, O notation • Basic probability (random variables, expectation) Helpful: • Familiarity with NP-Completeness, reductions • Basic number theory (modular arithmetic, etc) Reading No required text Computer Science/Mathematics Chapman & Hall/CRC If you want a text to follow along with: Second CRYPTOGRAPHY AND NETWORK SECURITY Cryptography is ubiquitous and plays a key role in ensuring data secrecy and Edition integrity as well as in securing computer systems more broadly. -

Indian Hieroglyphs

Indian hieroglyphs Indus script corpora, archaeo-metallurgy and Meluhha (Mleccha) Jules Bloch’s work on formation of the Marathi language (Bloch, Jules. 2008, Formation of the Marathi Language. (Reprint, Translation from French), New Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN: 978-8120823228) has to be expanded further to provide for a study of evolution and formation of Indian languages in the Indian language union (sprachbund). The paper analyses the stages in the evolution of early writing systems which began with the evolution of counting in the ancient Near East. Providing an example from the Indian Hieroglyphs used in Indus Script as a writing system, a stage anterior to the stage of syllabic representation of sounds of a language, is identified. Unique geometric shapes required for tokens to categorize objects became too large to handle to abstract hundreds of categories of goods and metallurgical processes during the production of bronze-age goods. In such a situation, it became necessary to use glyphs which could distinctly identify, orthographically, specific descriptions of or cataloging of ores, alloys, and metallurgical processes. About 3500 BCE, Indus script as a writing system was developed to use hieroglyphs to represent the ‘spoken words’ identifying each of the goods and processes. A rebus method of representing similar sounding words of the lingua franca of the artisans was used in Indus script. This method is recognized and consistently applied for the lingua franca of the Indian sprachbund. That the ancient languages of India, constituted a sprachbund (or language union) is now recognized by many linguists. The sprachbund area is proximate to the area where most of the Indus script inscriptions were discovered, as documented in the corpora. -

Battle Management Language: History, Employment and NATO Technical Activities

Battle Management Language: History, Employment and NATO Technical Activities Mr. Kevin Galvin Quintec Mountbatten House, Basing View, Basingstoke Hampshire, RG21 4HJ UNITED KINGDOM [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper is one of a coordinated set prepared for a NATO Modelling and Simulation Group Lecture Series in Command and Control – Simulation Interoperability (C2SIM). This paper provides an introduction to the concept and historical use and employment of Battle Management Language as they have developed, and the technical activities that were started to achieve interoperability between digitised command and control and simulation systems. 1.0 INTRODUCTION This paper provides a background to the historical employment and implementation of Battle Management Languages (BML) and the challenges that face the military forces today as they deploy digitised C2 systems and have increasingly used simulation tools to both stimulate the training of commanders and their staffs at all echelons of command. The specific areas covered within this section include the following: • The current problem space. • Historical background to the development and employment of Battle Management Languages (BML) as technology evolved to communicate within military organisations. • The challenges that NATO and nations face in C2SIM interoperation. • Strategy and Policy Statements on interoperability between C2 and simulation systems. • NATO technical activities that have been instigated to examine C2Sim interoperation. 2.0 CURRENT PROBLEM SPACE “Linking sensors, decision makers and weapon systems so that information can be translated into synchronised and overwhelming military effect at optimum tempo” (Lt Gen Sir Robert Fulton, Deputy Chief of Defence Staff, 29th May 2002) Although General Fulton made that statement in 2002 at a time when the concept of network enabled operations was being formulated by the UK and within other nations, the requirement remains extant. -

Chapter 3 – Block Ciphers and the Data Encryption Standard

Symmetric Cryptography Chapter 6 Block vs Stream Ciphers • Block ciphers process messages into blocks, each of which is then en/decrypted – Like a substitution on very big characters • 64-bits or more • Stream ciphers process messages a bit or byte at a time when en/decrypting – Many current ciphers are block ciphers • Better analyzed. • Broader range of applications. Block vs Stream Ciphers Block Cipher Principles • Block ciphers look like an extremely large substitution • Would need table of 264 entries for a 64-bit block • Arbitrary reversible substitution cipher for a large block size is not practical – 64-bit general substitution block cipher, key size 264! • Most symmetric block ciphers are based on a Feistel Cipher Structure • Needed since must be able to decrypt ciphertext to recover messages efficiently Ideal Block Cipher Substitution-Permutation Ciphers • in 1949 Shannon introduced idea of substitution- permutation (S-P) networks – modern substitution-transposition product cipher • These form the basis of modern block ciphers • S-P networks are based on the two primitive cryptographic operations we have seen before: – substitution (S-box) – permutation (P-box) (transposition) • Provide confusion and diffusion of message Diffusion and Confusion • Introduced by Claude Shannon to thwart cryptanalysis based on statistical analysis – Assume the attacker has some knowledge of the statistical characteristics of the plaintext • Cipher needs to completely obscure statistical properties of original message • A one-time pad does this Diffusion -

Cryptography: Decoding Student Learning

ABSTRACT PATTERSON, BLAIN ANTHONY. Cryptography: Decoding Student Learning. (Under the direction of Karen Keene.) Cryptography is a content field of mathematics and computer science, developed to keep information safe both when being sent between parties and stored. In addition to this, cryptography can also be used as a powerful teaching tool, as it puts mathematics in a dramatic and realistic setting. It also allows for a natural way to introduce topics such as modular arithmetic, matrix operations, and elementary group theory. This thesis reports the results of an analysis of students' thinking and understanding of cryptog- raphy using both the SOLO taxonomy and open coding as they participated in task based interviews. Students interviewed were assessed on how they made connections to various areas of mathematics through solving cryptography problems. Analyzing these interviews showed that students have a strong foundation in number theoretic concepts such as divisibility and modular arithmetic. Also, students were able to use probabil- ity intuitively to make sense of and solve problems. Finally, participants' SOLO levels ranged from Uni-structural to Extended Abstract, with Multi-Structural level being the most common (three participants). This gives evidence to suggest that students should be given the opportunity to make mathematical connections early and often in their academic careers. Results indicate that although cryptography should not be a required course by mathematics majors, concepts from this field could be introduced -

Sarasvati Civilization, Script and Veda Culture Continuum of Tin-Bronze Revolution

Sarasvati Civilization, script and Veda culture continuum of Tin-Bronze Revolution The monograph is presented in the following sections: Introduction including Abstract Section 1. Tantra yukti deciphers Indus Script Section 2. Momentous discovery of Soma samsthā yāga on Vedic River Sarasvati Basin Section 3. Binjor seal Section 4. Bhāratīya itihāsa, Indus Script hypertexts signify metalwork wealth-creation by Nāga-s in paṭṭaḍa ‘smithy’ = phaḍa फड ‘manufactory, company, guild, public office, keeper of all accounts, registers’ Section 5. Gaṇeśa pratimā, Gardez, Afghanistan is an Indus Script hypertext to signify Superintendent of phaḍa ‘metala manufactory’ Section 6. Note on the cobra hoods of Daimabad chariot Section 7 Note on Mohenjo-daro seal m0304: phaḍā ‘metals manufactory’ Section 8. Conclusion Introduction The locus of Veda culture and Sarasvati Civilization is framed by the Himalayan ranges and the Indian Ocean. 1 The Himalayan range stretches from Hanoi, Vietnam to Teheran, Iran and defines the Ancient Maritime Tin Route of the Indian Ocean – āsetu himācalam, ‘from the Setu to Himalayaś. Over several millennia, the Great Water Tower of frozen glacial waters nurtures over 3 billion people. The rnge is still growing, is dynamic because of plate tectonics of Indian plate juttng into and pushing up the Eurasian plate. This dynamic explains river migrations and consequent desiccation of the Vedic River Sarasvati in northwestern Bhāratam. Intermediation of the maritime tin trade through the Indian Ocean and waterways of Rivers Mekong, Irrawaddy, Salween, Ganga, Sarasvati, Sindhu, Persian Gulf, Tigris-Euphrates, the Mediterranean is done by ancient Meluhha (mleccha) artisans and traders, the Bhāratam Janam celebrated by R̥ ṣi Viśvāmitra in R̥ gveda (RV 3.53.12). -

The Impetus to Creativity in Technology

The Impetus to Creativity in Technology Alan G. Konheim Professor Emeritus Department of Computer Science University of California Santa Barbara, California 93106 [email protected] [email protected] Abstract: We describe the technical developments ensuing from two well-known publications in the 20th century containing significant and seminal results, a paper by Claude Shannon in 1948 and a patent by Horst Feistel in 1971. Near the beginning, Shannon’s paper sets the tone with the statement ``the fundamental problem of communication is that of reproducing at one point either exactly or approximately a message selected *sent+ at another point.‛ Shannon’s Coding Theorem established the relationship between the probability of error and rate measuring the transmission efficiency. Shannon proved the existence of codes achieving optimal performance, but it required forty-five years to exhibit an actual code achieving it. These Shannon optimal-efficient codes are responsible for a wide range of communication technology we enjoy today, from GPS, to the NASA rovers Spirit and Opportunity on Mars, and lastly to worldwide communication over the Internet. The US Patent #3798539A filed by the IBM Corporation in1971 described Horst Feistel’s Block Cipher Cryptographic System, a new paradigm for encryption systems. It was largely a departure from the current technology based on shift-register stream encryption for voice and the many of the electro-mechanical cipher machines introduced nearly fifty years before. Horst’s vision directed to its application to secure the privacy of computer files. Invented at a propitious moment in time and implemented by IBM in automated teller machines for the Lloyds Bank Cashpoint System. -

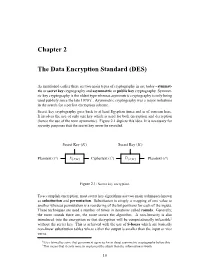

Chapter 2 the Data Encryption Standard (DES)

Chapter 2 The Data Encryption Standard (DES) As mentioned earlier there are two main types of cryptography in use today - symmet- ric or secret key cryptography and asymmetric or public key cryptography. Symmet- ric key cryptography is the oldest type whereas asymmetric cryptography is only being used publicly since the late 1970’s1. Asymmetric cryptography was a major milestone in the search for a perfect encryption scheme. Secret key cryptography goes back to at least Egyptian times and is of concern here. It involves the use of only one key which is used for both encryption and decryption (hence the use of the term symmetric). Figure 2.1 depicts this idea. It is necessary for security purposes that the secret key never be revealed. Secret Key (K) Secret Key (K) ? ? - - - - Plaintext (P ) E{P,K} Ciphertext (C) D{C,K} Plaintext (P ) Figure 2.1: Secret key encryption. To accomplish encryption, most secret key algorithms use two main techniques known as substitution and permutation. Substitution is simply a mapping of one value to another whereas permutation is a reordering of the bit positions for each of the inputs. These techniques are used a number of times in iterations called rounds. Generally, the more rounds there are, the more secure the algorithm. A non-linearity is also introduced into the encryption so that decryption will be computationally infeasible2 without the secret key. This is achieved with the use of S-boxes which are basically non-linear substitution tables where either the output is smaller than the input or vice versa. 1It is claimed by some that government agencies knew about asymmetric cryptography before this. -

Block Ciphers

BLOCK CIPHERS MTH 440 Block ciphers • Plaintext is divided into blocks of a given length and turned into output ciphertext blocks of the same length • Suppose you had a block cipher, E(x,k) where the input plaintext blocks,x, were of size 5-bits and a 4-bit key, k. • PT = 10100010101100101 (17 bits), “Pad” the PT so that its length is a multiple of 5 (we will just pad with 0’s – it doesn’t really matter) • PT = 10100010101100101000 • Break the PT into blocks of 5-bits each (x=x1x2x3x4) where each xi is 5 bits) • x1=10100, x2= 01010, x3=11001, x4=01000 • Ciphertext: c1c2c3c4 where • c1=E(x1,k1), c2=E(x2,k2), c3=E(x3,k3), c4=E(x4,k4) • (when I write the blocks next to each other I just mean concatentate them (not multiply) – we’ll do this instead of using the || notation when it is not confusing) • Note the keys might all be the same or all different What do the E’s look like? • If y = E(x,k) then we’ll assume that we can decipher to a unique output so there is some function, we’ll call it D, so that x = D(y,k) • We might define our cipher to be repeated applications of some function E either with the same or different keys, we call each of these applications “round” • For example we might have a “3 round” cipher: y Fk x E((() E E x, k1 , k 2)), k 3 • We would then decipher via 1 x Fk (,, y) D((() D D y, k3 k 2) k 1) S-boxes (Substitution boxes) • Sometimes the “functions” used in the ciphers are just defined by a look up table that are often referred to “S- boxes” •x1 x 2 x 3 S(x 1 x 2 x 3 ) Define a 4-bit function with a 3-bit key 000 -

Feistel Cipher

Chapter 3 – Block Ciphers and the CryptographyCryptography andand Data Encryption Standard Network Security Network Security All the afternoon Mungo had been working on Stern's code, principally with the aid of the latest ChapterChapter 33 messages which he had copied down at the Nevin Square drop. Stern was very confident. He must be well aware London Central knew Fifth Edition about that drop. It was obvious that they didn't care how often Mungo read their messages, so by William Stallings confident were they in the impenetrability of the Lecture slides by Lawrie Brown code. —Talking to Strange Men, Ruth Rendell (with edits by RHB) Outline Modern Block Ciphers • will consider: • now look at modern block ciphers – Block vs stream ciphers • one of the most widely used types of – Feistel cipher design & structure cryptographic algorithms – DES • provide secrecy/authentication services • details • Initially look at Data Encryption Standard • strength (DES) to illustrate block cipher design – Differential & linear cryptanalysis issues – Block cipher design principles Block vs Stream Ciphers Block vs Stream Ciphers Block vs Stream Ciphers • block ciphers process messages in blocks, each of which is then en/decrypted • like a substitution on very big characters – 64 -bits or more (these days, 128 or more) • stream ciphers process messages a bit or byte at a time when en/de -crypting • many current ciphers are block ciphers – better analysed – broader range of applications Block Cipher Principles Ideal Block Cipher • many symmetric block ciphers