Local Anesthetics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 11 Local Anesthetics

Chapter LOCAL ANESTHETICS 11 Kenneth Drasner HISTORY MECHANISMS OF ACTION AND FACTORS ocal anesthesia can be defined as loss of sensation in AFFECTING BLOCK L a discrete region of the body caused by disruption of Nerve Conduction impulse generation or propagation. Local anesthesia can Anesthetic Effect and the Active Form of the be produced by various chemical and physical means. Local Anesthetic However, in routine clinical practice, local anesthesia is Sodium Ion Channel State, Anesthetic produced by a narrow class of compounds, and recovery Binding, and Use-Dependent Block is normally spontaneous, predictable, and complete. Critical Role of pH Lipid Solubility Differential Local Anesthetic Blockade Spread of Local Anesthesia after Injection HISTORY PHARMACOKINETICS Cocaine’s systemic toxicity, its irritant properties when Local Anesthetic Vasoactivity placed topically or around nerves, and its substantial Metabolism potential for physical and psychological dependence gene- Vasoconstrictors rated interest in identification of an alternative local 1 ADVERSE EFFECTS anesthetic. Because cocaine was known to be a benzoic Systemic Toxicity acid ester (Fig. 11-1), developmental strategies focused Allergic Reactions on this class of chemical compounds. Although benzo- caine was identified before the turn of the century, its SPECIFIC LOCAL ANESTHETICS poor water solubility restricted its use to topical anesthe- Amino-Esters sia, for which it still finds some limited application in Amino-Amide Local Anesthetics modern clinical practice. The -

Bupivacaine Injection Bp

PRODUCT MONOGRAPH INCLUDING CONSUMER INFORMATION BUPIVACAINE INJECTION BP Bupivacaine hydrochloride 0.25% (2.5 mg/mL) and 0.5% (5 mg/mL) Local Anaesthetic SteriMax Inc. Date of Preparation: 2770 Portland Dr. July 10, 2015 Oakville, ON, L6H 6R4 Submission Control No: 180156 Bupivacaine Injection Page 1 of 28 Table of Contents PART I: HEALTH PROFESSIONAL INFORMATION .................................................................... 3 SUMMARY PRODUCT INFORMATION ................................................................................... 3 INDICATIONS AND CLINICAL USE ......................................................................................... 3 CONTRAINDICATIONS .............................................................................................................. 3 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS ............................................................................................. 4 ADVERSE REACTIONS ............................................................................................................... 9 DRUG INTERACTIONS ............................................................................................................. 10 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION ......................................................................................... 13 OVERDOSAGE ........................................................................................................................... 16 ACTION AND CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY ....................................................................... 18 STORAGE -

A Randomised, Non-Inferiority Study of Chloroprocaine 2% and Ropivacaine

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN A randomised, non‑inferiority study of chloroprocaine 2% and ropivacaine 0.75% in ultrasound‑guided axillary block Irene Sulyok1, Claudio Camponovo2, Oliver Zotti1, Werner Haslik3, Markus Köstenberger4, Rudolf Likar4, Chiara Leuratti5, Elisabetta Donati6 & Oliver Kimberger1,7* Chloroprocaine is a short‑acting local anaesthetic with a rapid onset of action and an anaesthesia duration up to 60 min. In this pivotal study success rates, onset and remission of motor and sensory block and safety of chloroprocaine 2% was compared to ropivacaine 0.75% for short‑duration distal upper limb surgery with successful block rates as primary outcome. The study was designed as a prospective, randomised, multi‑centre, active‑controlled, double‑blind, parallel‑group, non‑inferiority study, performed in 4 European hospitals with 211 patients scheduled for short duration distal upper limb surgery under axillary plexus block anaesthesia. Patients received either ultrasound guided axillary block with 20 ml chloroprocaine 2%, or with 20 ml ropivacaine 0.75%. Successful block was defned as block without any supplementation in the frst 45 min calculated from the time of readiness for surgery. 90.8% patients achieved a successful block with chloroprocaine 2% and 92.9% patients with Ropivacaine 0.75%, thus non‑inferiority was demonstrated (10% non inferiority margin; 95% CI − 0.097, 0.039; p = 0.02). Time to onset of block was not signifcantly diferent between the groups. Median time to motor and sensory block regression was signifcantly shorter as was time to home discharge (164 [155–170] min for chloroprocaine versus 380 [209–450] for the ropivacaine group, p < 0.001). -

Mepivacaine Hydrochloride Injection

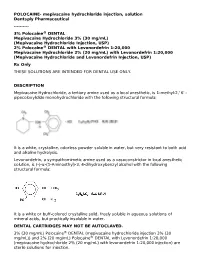

POLOCAINE- mepivacaine hydrochloride injection, solution Dentsply Pharmaceutical ---------- 3% Polocaine® DENTAL Mepivacaine Hydrochloride 3% (30 mg/mL) (Mepivacaine Hydrochloride Injection, USP) 2% Polocaine® DENTAL with Levonordefrin 1:20,000 Mepivacaine Hydrochloride 2% (20 mg/mL) with Levonordefrin 1:20,000 (Mepivacaine Hydrochloride and Levonordefrin Injection, USP) Rx Only THESE SOLUTIONS ARE INTENDED FOR DENTAL USE ONLY. DESCRIPTION Mepivacaine Hydrochloride, a tertiary amine used as a local anesthetic, is 1-methyl-2,' 6' - pipecoloxylidide monohydrochloride with the following structural formula: It is a white, crystalline, odorless powder soluble in water, but very resistant to both acid and alkaline hydrolysis. Levonordefrin, a sympathomimetic amine used as a vasoconstrictor in local anesthetic solution, is (-)-α-(1-Aminoethyl)-3, 4-dihydroxybenzyl alcohol with the following structural formula: It is a white or buff-colored crystalline solid, freely soluble in aqueous solutions of mineral acids, but practically insoluble in water. DENTAL CARTRIDGES MAY NOT BE AUTOCLAVED. 3% (30 mg/mL) Polocaine® DENTAL (mepivacaine hydrochloride injection 3% (30 mg/mL)) and 2% (20 mg/mL) Polocaine® DENTAL with Levonordefrin 1:20,000 (mepivacaine hydrochloride 2% (20 mg/mL) with levonordefrin 1:20,000 injection) are sterile solutions for injection. sterile solutions for injection. COMPOSITION: CARTRIDGE Each mL contains: 2% 3% Mepivacaine Hydrochloride 20 mg 30 mg Levonordefrin 0.05 mg - Sodium Chloride 4 mg 6 mg Potassium metabisulfite 1.2 mg - Edetate disodium 0.25 mg - Sodium Hydroxide q.s. ad pH; Hydrochloric 0.5 mg - Acid Water For Injection, qs. ad. 1 mL 1 mL The pH of the 2% cartridge solution is adjusted between 3.3 and 5.5 with NaOH. -

4% Citanest® Plain Dental (Prilocaine Hydrochloride Injection, USP) for Local Anesthesia in Dentistry

4% Citanest® Plain Dental (Prilocaine Hydrochloride Injection, USP) For Local Anesthesia in Dentistry Rx only DESCRIPTION 4% Citanest Plain Dental (prilocaine HCI Injection, USP), is a sterile, non-pyrogenic isotonic solution that contains a local anesthetic agent and is administered parenterally by injection. See INDICATIONS AND USAGE for specific uses. The quantitative composition is shown in Table 1. 4% Citanest Plain Dental contains prilocaine HCl, which is chemically designated as propanamide, N-(2- methyl-phenyl) -2- (propylamino)-, monohydrochloride and has the following structural formula: Parenteral drug products should be inspected visually for particulate matter and discoloration prior to administration. The specific quantitative composition is shown in Table 1. TABLE 1. COMPOSITION Product Identification Formula (mg/mL) Prilocaine HCl pH 4% Citanest® Plain Dental 40.0 6.0 to 7.0 Note: Sodium hydroxide or hydrochloric acid may be used to adjust the pH of 4% Citanest Plain Dental Injection. CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY Mechanism of Action: Prilocaine stabilizes the neuronal membrane by inhibiting the ionic fluxes required for the initiation and conduction of impulses, thereby effecting local anesthetic action. Onset and Duration of Action: When used for infiltration injection in dental patients, the time of onset of anesthesia averages less than 2 minutes with an average duration of soft tissue anesthesia of approximately 2 hours. Based on electrical stimulation studies, 4% Citanest Plain Dental Injection provides a duration of pulpal anesthesia of approximately 10 minutes in maxillary infiltration injections. In clinical studies, this has been found to provide complete anesthesia for procedures lasting an average of 20 minutes. When used for inferior alveolar nerve block, the time of onset of 4% Citanest Plain Dental Injection averages less than three minutes with an average duration of soft tissue anesthesia of approximately 2 ½hours. -

Classification of Medicinal Drugs and Driving: Co-Ordination and Synthesis Report

Project No. TREN-05-FP6TR-S07.61320-518404-DRUID DRUID Driving under the Influence of Drugs, Alcohol and Medicines Integrated Project 1.6. Sustainable Development, Global Change and Ecosystem 1.6.2: Sustainable Surface Transport 6th Framework Programme Deliverable 4.4.1 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Due date of deliverable: 21.07.2011 Actual submission date: 21.07.2011 Revision date: 21.07.2011 Start date of project: 15.10.2006 Duration: 48 months Organisation name of lead contractor for this deliverable: UVA Revision 0.0 Project co-funded by the European Commission within the Sixth Framework Programme (2002-2006) Dissemination Level PU Public PP Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission x Services) RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission Services) CO Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission Services) DRUID 6th Framework Programme Deliverable D.4.4.1 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Page 1 of 243 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Authors Trinidad Gómez-Talegón, Inmaculada Fierro, M. Carmen Del Río, F. Javier Álvarez (UVa, University of Valladolid, Spain) Partners - Silvia Ravera, Susana Monteiro, Han de Gier (RUGPha, University of Groningen, the Netherlands) - Gertrude Van der Linden, Sara-Ann Legrand, Kristof Pil, Alain Verstraete (UGent, Ghent University, Belgium) - Michel Mallaret, Charles Mercier-Guyon, Isabelle Mercier-Guyon (UGren, University of Grenoble, Centre Regional de Pharmacovigilance, France) - Katerina Touliou (CERT-HIT, Centre for Research and Technology Hellas, Greece) - Michael Hei βing (BASt, Bundesanstalt für Straßenwesen, Germany). -

Properties and Units in Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology

Pure Appl. Chem., Vol. 72, No. 3, pp. 479–552, 2000. © 2000 IUPAC INTERNATIONAL FEDERATION OF CLINICAL CHEMISTRY AND LABORATORY MEDICINE SCIENTIFIC DIVISION COMMITTEE ON NOMENCLATURE, PROPERTIES, AND UNITS (C-NPU)# and INTERNATIONAL UNION OF PURE AND APPLIED CHEMISTRY CHEMISTRY AND HUMAN HEALTH DIVISION CLINICAL CHEMISTRY SECTION COMMISSION ON NOMENCLATURE, PROPERTIES, AND UNITS (C-NPU)§ PROPERTIES AND UNITS IN THE CLINICAL LABORATORY SCIENCES PART XII. PROPERTIES AND UNITS IN CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY AND TOXICOLOGY (Technical Report) (IFCC–IUPAC 1999) Prepared for publication by HENRIK OLESEN1, DAVID COWAN2, RAFAEL DE LA TORRE3 , IVAN BRUUNSHUUS1, MORTEN ROHDE1, and DESMOND KENNY4 1Office of Laboratory Informatics, Copenhagen University Hospital (Rigshospitalet), Copenhagen, Denmark; 2Drug Control Centre, London University, King’s College, London, UK; 3IMIM, Dr. Aiguader 80, Barcelona, Spain; 4Dept. of Clinical Biochemistry, Our Lady’s Hospital for Sick Children, Crumlin, Dublin 12, Ireland #§The combined Memberships of the Committee and the Commission (C-NPU) during the preparation of this report (1994–1996) were as follows: Chairman: H. Olesen (Denmark, 1989–1995); D. Kenny (Ireland, 1996); Members: X. Fuentes-Arderiu (Spain, 1991–1997); J. G. Hill (Canada, 1987–1997); D. Kenny (Ireland, 1994–1997); H. Olesen (Denmark, 1985–1995); P. L. Storring (UK, 1989–1995); P. Soares de Araujo (Brazil, 1994–1997); R. Dybkær (Denmark, 1996–1997); C. McDonald (USA, 1996–1997). Please forward comments to: H. Olesen, Office of Laboratory Informatics 76-6-1, Copenhagen University Hospital (Rigshospitalet), 9 Blegdamsvej, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark. E-mail: [email protected] Republication or reproduction of this report or its storage and/or dissemination by electronic means is permitted without the need for formal IUPAC permission on condition that an acknowledgment, with full reference to the source, along with use of the copyright symbol ©, the name IUPAC, and the year of publication, are prominently visible. -

Pharmacology for Regional Anaesthesia

Sign up to receive ATOTW weekly - email [email protected] PHARMACOLOGY FOR REGIONAL ANAESTHESIA ANAESTHESIA TUTORIAL OF THE WEEK 49 26TH MARCH 2007 Dr J. Hyndman Questions 1) List the factors that determine the duration of a local anaesthetic nerve block. 2) How much more potent is bupivocaine when compared to lidocaine? 3) How does the addition of epinephrine increase the duration of a nerve block? 4) What is the maximum recommended dose of: a) Plain lidocaine? b) Lidocaine with epinephrine 1:200 000? 5) What is the recommended dose of a) Clonidine to be added to local anaesthetic solution? b) Sodium bicarbonate? In this section, I will discuss the pharmacology of local anaesthetic agents and then describe the various additives used with these agents. I will also briefly cover the pharmacology of the other drugs commonly used in regional anaesthesia practice. A great number of drugs are used in regional anaesthesia. I am sure no two anaesthetists use exactly the same combinations of drugs. I will emphasise the drugs I use in my own practice but the reader may select a different range of drugs according to his experience and drug availability. The important point is to use the drugs you are familiar with. For the purposes of this discussion, I am going to concentrate on the following drugs: Local anaesthetic agents Lidocaine Prilocaine Bupivacaine Levobupivacaine Ropivacaine Local anaesthetic additives Epinephrine Clonidine Felypressin Sodium bicarbonate Commonly used drugs Midazolam/Temazepam Fentanyl Ephedrine Phenylephrine Atropine Propofol ATOTW 49 Pharmacology for regional anaesthesia 29/03/2007 Page 1 of 6 Sign up to receive ATOTW weekly - email [email protected] Ketamine EMLA cream Ametop gel Naloxone Flumazenil PHARMACOLOGY OF LOCAL ANAESTHETIC DRUGS History In 1860, cocaine was extracted from the leaves of the Erythroxylon coca bush. -

The Effect of Different Doses of Chloroprocaine on Saddle Anesthesia in Perianal Surgery1

10 – ORIGINAL ARTICLE CLINICAL INVESTIGATION The effect of different doses of chloroprocaine on saddle anesthesia in perianal surgery1 Ying ZhangI, Yang BaoII, Linggeng LiIII, Dongping ShiIV IMaster, Department of Anesthesiology, Shanghai Jiading Central Hospital, Shanghai, China. Conception and design of the study; acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data; manuscript writing, final approval. IIMaster, Department of Anesthesiology, Shanghai Jiading Central Hospital, Shanghai, China. Conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision. IIIMaster, Department of Anesthesiology, Shanghai Jiading Central Hospital, Shanghai, China. Histopathological examinations, critical revision. IVMaster, Department of Anesthesiology, Shanghai Jiading Central Hospital, Shanghai, China. Acquisition and interpretation of data, final approval. ABSTRACT PURPOSE: To investigate a saddle anesthesia with different doses of chloroprocaine in perianal surgery. METHODS: Total 60 Patients aged 18–75 years (Anesthesiologists grade I or II) scheduled to receive perianal surgery. Patients using saddle anesthesia were randomized to group A, group B and group C with the same concentration (0.5%) chloroprocaine with different doses 1.0 mL, 0.8 mL and 0.6 mL, respectively. Systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), heart rate (HR) and the sensory and motor block were recorded to evaluate the anesthesia effect of chloroprocaine in each group. RESULTS: The duration of sensory block of group C is shorter than those of group A and B. The maximum degree of motor block is observed (group C: 0 level, group A: III level; and group B: I level) after 15 minutes. Besides, there was a better anesthetic effect in group B than group A and group C, such as walking after saddle anesthesia. -

Femoral Nerve Block Versus Spinal Anesthesia for Lower Limb

Alexandria Journal of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care 44 Femoral Nerve Block versus Spinal Anesthesia for Lower Limb Peripheral Vascular Surgery By Ahmed Mansour, MD Assistant Professor of Anesthesia, Faculty of Medicine, Alexandria University. Abstract Perioperative cardiac complications occur in 4% to 6% of patients undergoing infrainguinal revascularization under general, spinal, or epidural anesthesia. The risk may be even greater in patients whose cardiac disease cannot be fully evaluated or treated before urgent limb salvage operations. Prompted by these considerations, we investigated the feasibility and results of using femoral nerve block with infiltration of the genito4femoral nerve branches in these high-risk patients. Methods: Forty peripheral vascular reconstruction of lower limbs were performed under either spinal anesthesia (20 patients) or femoral nerve block with infiltration of genito-femoral nerve branches supplemented with local infiltration at the site of dissection as needed (20 patients). All patients had arterial lines. Arterial blood pressure and electrocardiographic monitoring was continued during surgery, in PACU and in the intensive care units. Results: Operations included femoral-femoral, femoral-popliteal bypass grafting and thrombectomy. The intra-operative events showed that the mean time needed to perform the block and dose of analgesics and sedatives needed during surgery was greater in group I (FNB,) compared to group II [P=0.01*, P0.029* , P0.039*], however, the time needed to start surgery was shorter in group I than in group II [P=0. 039]. There were no block failures in either group, but local infiltration in the area of the dissection with 2 ml (range 1-5 ml) of 1% lidocaine was required in 4 (20%) patients in FNB group vs none in the spinal group. -

Bupivacaine Hcl Rx Only 0.5% with Epinephrine 1:200,000 (As Bitartrate) (Bupivacaine Hydrochloride and Epinephrine Injection, USP)

Bupivacaine HCl Rx only 0.5% with epinephrine 1:200,000 (as bitartrate) (bupivacaine hydrochloride and epinephrine injection, USP) THIS SOLUTION IS INTENDED FOR DENTAL USE. DESCRIPTION Bupivacaine hydrochloride is (±) -1-Butyl-2´,6´-pipecoloxylidide monohydrochloride, monohydrate, a white crystalline powder that is freely soluble in 95 percent ethanol, soluble in water, and slightly soluble in chloroform or acetone. It has the following structural formula: Epinephrine is (-)-3,4-Dihydroxy-α-[(methylamino)methyl] benzyl alcohol. It has the following structural formula: BUPIVACAINE HCl is available in a sterile isotonic solution with epinephrine (as bitartrate) 1:200,000. Solutions of BUPIVACAINE HCl containing epinephrine may not be autoclaved. BUPIVACAINE HCl is related chemically and pharmacologically to the aminoacyl local anesthetics. It is a homologue of mepivacaine and is chemically related to lidocaine. All three of these anesthetics contain an amide linkage between the aromatic nucleus and the amino or piperidine group. They differ in this respect from the procaine-type local anesthetics, which have an ester linkage. CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY BUPIVACAINE HCl stabilizes the neuronal membrane and prevents the initiation and transmission of nerve impulses, thereby effecting local anesthesia. The onset of action following dental injections is usually 2 to 10 minutes and anesthesia may last two or three times longer than lidocaine and mepivacaine for dental use, in many patients up to 7 hours. The duration of anesthetic effect is prolonged by the addition of epinephrine 1:200,000. It has also been noted that there is a period of analgesia that persists after the return of sensation, during which time the need for strong analgesic is reduced. -

Lidocaine Infusion for Analgesia MOA Pharmacology 1

Lidocaine Infusion for Analgesia MOA Pharmacology 1. Attenuation of proinflammatory effects: Ø Hepatic metabolism with high extraction ratio; Ø Blocks polymorphonuclear granulocyte priming, plasma clearance is 10 ml/kg/min13 reducing release of cytokines & reactive oxygen species1 Ø Adjust dose based on hepatic function and 2. Diminish nociceptive signaling to central nervous system: blood flow Ø Inhibition of G-protein-mediated effects2 Ø Renal clearance of metabolites Ø Reduces sensitivity & activity of spinal cord neurons Ø Context-sensitive half-time after a 3-day infusion is (glycine and NMDA receptor mediated)3,4 ∼20–40 min Ø Clinical effect of lidocaine tends to exceed the 5 3. Reduces ectopic activity of injured afferent nerves duration of the infusion by 5.5 times the half-life, supporting the putative preventive analgesia effect14 Perioperative Use Dosing Ø IV local anesthetic infusions have been used safely for pain control in the perioperative setting since the early 1950’s6,7 Infusion: 2mg/kg/hr (range 1.5-3 mg/kg/hr) Ø Reduce pain, nausea, ileus duration, opioid requirement, Loading dose: 1.5mg/kg (range 1-2 mg/kg) and length of hospital stay Ø Strongly consider bolus to rapidly achieve therapeutic concentration, otherwise steady state 9-12 Evidence for Specific Surgeries: reached in 4-8 hr Ø Strong: Open & laparoscopic abdominal; Reduces Max dose: 4.5 mg/kg postoperative pain, speeds return of bowel function, Ø Consider total dose from other local anesthetics reduces PONV, reduces length of hospital stay (e.g. regional anesthesia, periarticular injections, & Ø Moderate: Open prostatectomy, thoracic procedures, local infiltration) ambulatory surgery, and major spine; Reduces Continuous infusions up to 3 mg/kg/hr have been postoperative pain and opioid consumption shown to be safe Ø Moderate: Breast; Prevention of chronic postsurgical pain Ø Reduce infusion rate in patients with impaired Ø No benefit: Total abdominal hysterectomy, total hip drug metabolism & clearance (i.e.