Shaping the Literary Image of the Devil in Reformation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 18, 2018-No Deal with the Devil

Genesis 2:15-17; 3:1-13; Hebrews 4:14-16; Matthew 4:1-11 February 18, 2018 First Sunday in Lent Preached by Philip Gladden at the Wallace Presbyterian Church, Wallace, NC NO DEAL WITH THE DEVIL Let us pray: Let the words of my mouth and the meditation of my heart be acceptable to you, O Lord, our rock and our redeemer. Amen. Today at 2:00 p.m. the UNC-Wilmington theater department will present “Dr. Faustus.” The production will be set in a rock and roll dream world and is based on the 16th century play by Christopher Marlowe. The full title of the original play was “The Tragical History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus. Marlowe fashioned his play on old German folk tales about Doctor Faustus, an academic who made a deal with the devil, Lucifer, who is represented by the character Mephistophilis. Faustus gets bored with the regular academic subjects and trades his soul for twenty-four years of knowing and practicing the black arts and magic. Despite his misgivings about his deal with the devil as the end gets nearer, and frantic attempts to get out of the deal, Faustus is killed at the stroke of midnight.1 One legend says that when Doctor Faustus was first performed, actual devils showed up on stage and drove some audience members crazy. From that tragic story we get the phrase “a Faustian bargain.” This means trading in your values and morals, exchanging who you really are for some apparently awesome short-term goal. -

HIP HOP & Philosophy

Devil and Philosophy 2nd pages_HIP HOP & philosophy 4/8/14 10:43 AM Page 195 21 Souls for Sale JEFF EWING F Y O Selling your soul to the Devil in exchaPnge for a longer life, wealth, beauty, power, or skill has long been a theme in Obooks, movies, and even music. Souls have Obeen sold for Rknowledge and pleasure (Faust), eternal youth (Dorian Gray), the ability to play the guitar (Tommy JohnCson in O Brother, Where Art P Thou?) or the harmonica (Willie “Blind Do g Fulton Smoke House” Brown in the 1986 Emovie, Crossroads), or for rock’n’roll itself (the way Black SCabbath did on thDeir 1975 greatest hits album, We Sold Our Soul for Rock’n’ERoll). The selling of aN soul as an object of exchange for nearly any- thing, as a sort of fictitious comTmodity with nearly universal exchange valuAe, makes it perChaps the most unique of all possi- ble commVodities (and as such, contracts for the sales of souls are the most unique of aEll possible contracts). One theorist in partiDcular, Karl MaRrx (1818–1883), elaborately analyzed con- tracts, exchange, and “the commodity” itself, along with all the hAidden implicatRions of commodities and the exchange process. Let’s see what Marx has to tell us about the “political economy” of the FaustOian bargain with the Devil, and try to uncover what it trulyC is to sell your soul. N Malice and Malleus Maleficarum UWhile the term devil is sometimes used to refer to minor, lesser demons, in Western religions the term refers to Satan, the fallen angel who led a rebellion against God and was banished from Heaven. -

Faust Among the Witches: Towards an Ethics of Representation —David Hawkes

Faust Among the Witches: Towards an Ethics of Representation —David Hawkes I 1. Money rules the postmodern world, and money is an efficacious, or "performative," sign: a medium of representation that attains practical power. As we might expect, therefore, the concept of the performative sign is theoretically central to the postmodern era' s philosophy, politics, psychology, linguistics and -- a forteriori -- its economics. All of these disciplines, in their postmodern forms, privilege the performative, rather than the denotative, aspect of signs. They all assume that signs do things, and that the objective world is constructed for us via the realm of signification. In the work of such philosophers as Jacques Derrida and Judith Butler, the performative sign even acquires a vague association with political radicalism, since its power can be used to deconstruct such allegedly repressive chimeras as essence and self-identity. 2. The argument that signs are performative by nature leads to the conclusion that there is no prelinguistic or nonmaterial human subject, since subjective intention is irrelevant to the sign's efficacy. The idea that the subject is material thus takes its place alongside the notion that representation is efficacious as a central tenet of postmodern thought. It is not difficult to point to the connection between these ideas in the field of "economics." Money is an externalized representation of abstract human labor power -- that is to say, of human subjective activity, of human life. In addition to being a system of autonomous representation, then, money is the incarnation of objectified subjectivity. It is thus hardly surprising to find that the idea that the subject is material, that it is an object, is very prevalent in postmodern thought, or that materialism dominates intellectual disciplines from sociobiology to literary criticism. -

Defending Faith

Spätmittelalter, Humanismus, Reformation Studies in the Late Middle Ages, Humanism and the Reformation herausgegeben von Volker Leppin (Tübingen) in Verbindung mit Amy Nelson Burnett (Lincoln, NE), Berndt Hamm (Erlangen) Johannes Helmrath (Berlin), Matthias Pohlig (Münster) Eva Schlotheuber (Düsseldorf) 65 Timothy J. Wengert Defending Faith Lutheran Responses to Andreas Osiander’s Doctrine of Justification, 1551– 1559 Mohr Siebeck Timothy J. Wengert, born 1950; studied at the University of Michigan (Ann Arbor), Luther Seminary (St. Paul, MN), Duke University; 1984 received Ph. D. in Religion; since 1989 professor of Church History at The Lutheran Theological Seminary at Philadelphia. ISBN 978-3-16-151798-3 ISSN 1865-2840 (Spätmittelalter, Humanismus, Reformation) Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2012 by Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen, Germany. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher’s written permission. This applies particularly to reproduc- tions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was typeset by Martin Fischer in Tübingen using Minion typeface, printed by Gulde- Druck in Tübingen on non-aging paper and bound Buchbinderei Spinner in Ottersweier. Printed in Germany. Acknowledgements Thanks is due especially to Bernd Hamm for accepting this manuscript into the series, “Spätmittelalter, Humanismus und Reformation.” A special debt of grati- tude is also owed to Robert Kolb, my dear friend and colleague, whose advice and corrections to the manuscript have made every aspect of it better and also to my doctoral student and Flacius expert, Luka Ilic, for help in tracking down every last publication by Matthias Flacius. -

Joseph Smith and Diabolism in Early Mormonism 1815-1831

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2021 "He Beheld the Prince of Darkness": Joseph Smith and Diabolism in Early Mormonism 1815-1831 Steven R. Hepworth Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Hepworth, Steven R., ""He Beheld the Prince of Darkness": Joseph Smith and Diabolism in Early Mormonism 1815-1831" (2021). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 8062. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/8062 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "HE BEHELD THE PRINCE OF DARKNESS": JOSEPH SMITH AND DIABOLISM IN EARLY MORMONISM 1815-1831 by Steven R. Hepworth A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Approved: Patrick Mason, Ph.D. Kyle Bulthuis, Ph.D. Major Professor Committee Member Harrison Kleiner, Ph.D. D. Richard Cutler, Ph.D. Committee Member Interim Vice Provost of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2021 ii Copyright © 2021 Steven R. Hepworth All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT “He Beheld the Prince of Darkness”: Joseph Smith and Diabolism in Early Mormonism 1815-1831 by Steven R. Hepworth, Master of Arts Utah State University, 2021 Major Professor: Dr. Patrick Mason Department: History Joseph Smith published his first known recorded history in the preface to the 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon. -

"With His Blood He Wrote"

:LWK+LV%ORRG+H:URWH )XQFWLRQVRIWKH3DFW0RWLILQ)DXVWLDQ/LWHUDWXUH 2OH-RKDQ+ROJHUQHV Thesis for the degree of philosophiae doctor (PhD) at the University of Bergen 'DWHRIGHIHQFH0D\ © Copyright Ole Johan Holgernes The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Year: 2017 Title: “With his Blood he Wrote”. Functions of the Pact Motif in Faustian Literature. Author: Ole Johan Holgernes Print: AiT Bjerch AS / University of Bergen 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following for their respective roles in the creation of this doctoral dissertation: Professor Anders Kristian Strand, my supervisor, who has guided this study from its initial stages to final product with a combination of encouraging friendliness, uncompromising severity and dedicated thoroughness. Professor Emeritus Frank Baron from the University of Kansas, who encouraged me and engaged in inspiring discussion regarding his own extensive Faustbook research. Eve Rosenhaft and Helga Muellneritsch from the University of Liverpool, who have provided erudite insights on recent theories of materiality of writing, sign and indexicality. Doctor Julian Reidy from the Mann archives in Zürich, with apologies for my criticism of some of his work, for sharing his insights into the overall structure of Thomas Mann’s Doktor Faustus, and for providing me with some sources that have been valuable to my work. Professor Erik Bjerck Hagen for help with updated Ibsen research, and for organizing the research group “History, Reception, Rhetoric”, which has provided a platform for presentations of works in progress. Professor Lars Sætre for his role in organizing the research school TBLR, for arranging a master class during the final phase of my work, and for friendly words of encouragement. -

They Sold Their Soul to the Devil Have You Noticed the Number of Hollywood and Music Industry Stars Claiming to Have Sold Their

They Sold Their Soul to the Devil Have you noticed the number of Hollywood and music industry stars claiming to have sold their souls to the devil? Souled out stars. •“Sold my soul, from heaven into hell.” - 30 Seconds to Mars •“Sell his soul for cheap. Let’s make a deal, sell me your soul. Designer of the devil.” - 50 Cent •“I sold my soul to the devil in L.A” - Aaron Lewis •“Some sell their soul for the easy road. The devil’s always buying. I can’t count the ones I’ve known who fell right into line.” - Aaron Tippin •“‘I sold my soul to the devil.” - Abi Titmuss •“I’m just a demon that means well. Freelance for God, but do the work of Satan.” - Ab- Soul •“Hey Satan, pay my dues. I’m gonna take you to hell, I’m gonna get ya Satan.” - AC/DC •“There’s plenty of money to be had. But you also lose your soul.” - Alan Alda •“And tempt the soul of any man. Between the devil and me. The gates of hell swing open.” - Alan Jackson •“Dr. Dre told me he sold his soul to the devil for a million bucks.” - Alonzo Williams •“The dark covers me and I cannot run now.” - Amy Winehouse •“I sold my soul.” - Andrew W.K. •“But when it comes time to decide your fate, they’ll sign you on the line right next to Satan. Cause’ they don’t care about us. They just use us up.” - Asher Roth •“I sold my soul to the devil.” - Aubrey Plaza •“Dance with the devil. -

The Formula of Concord As a Model for Discourse in the Church

21st Conference of the International Lutheran Council Berlin, Germany August 27 – September 2, 2005 The Formula of Concord as a Model for Discourse in the Church Robert Kolb The appellation „Formula of Concord“ has designated the last of the symbolic or confessional writings of the Lutheran church almost from the time of its composition. This document was indeed a formulation aimed at bringing harmony to strife-ridden churches in the search for a proper expression of the faith that Luther had proclaimed and his colleagues and followers had confessed as a liberating message for both church and society fifty years earlier. This document is a formula, a written document that gives not even the slightest hint that it should be conveyed to human ears instead of human eyes. The Augsburg Confession had been written to be read: to the emperor, to the estates of the German nation, to the waiting crowds outside the hall of the diet in Augsburg. The Apology of the Augsburg Confession, it is quite clear from recent research,1 followed the oral form of judicial argument as Melanchthon presented his case for the Lutheran confession to a mythically yet neutral emperor; the Apology was created at the yet not carefully defined border between oral and written cultures. The Large Catechism reads like the sermons from which it was composed, and the Small Catechism reminds every reader that it was written to be recited and repeated aloud. The Formula of Concord as a „Binding Summary“ of Christian Teaching In contrast, the „Formula of Concord“ is written for readers, a carefully- crafted formulation for the theologians and educated lay people of German Lutheran churches to ponder and study. -

The Law in Formula VI James A

Volume 69:3-4 July/October 2005 Table of Contents The Third Use of the Law: Keeping Up to Date with an Old Issue Lawrence R. Rast .................................................................... 187 A Third Use of the Law: Is the Phrase Necessary? Lawrence M. Vogel ..................................................................191 God's Law, God's Gospel, and Their Proper Distinction: A Sure Guide Through the Moral Wasteland of Postmodernism Louis A. Smith .......................................................................... 221 The Third Use of the Law: Resolving The Tension David P. Scaer ........................................................................... 237 Changing Definitions: The Law in Formula VI James A. Nestingen ................................................................. 259 Beyond the Impasse: Re-examining the Third Use of the Law Mark C. Mattes ......................................................................... 271 Looking into the Heart of Missouri: Justification, Sanctification, and the Third Use of the Law Carl Beckwith ............................................................................ 293 Choose Life! Walter Obare Omawanza ........................................................ 309 CTQ 69 (2005): 259-270 Changing Definitions: The Law in Formula VI James A. Nestingen There are a couple of key theological issues percolating through the dispute over the third use of the law. When they are isolated, they illustrate some of the key historical differences between Luther and Melanchthon, and beyond them, between Luther and the theologians who drafted Article VI of the Formula of Concord. The first issue is the end of the law, an assertion that emerged early in the Reformation out of Luther and Melanchthon's consideration of Roman 10:4, where Paul states that "Christ is the end [rCAos] of the law, that all who believe may be justified." Luther and Melanchthon both picked up what had generally been either passed over or minimized by the tradition, the sense of termination that is also included in riAos. -

Download Thesis

A Comparative Analysis of the Distinction between Law and Gospel in Gerhard Forde and Confessional Lutheranism. By Jordan Cooper A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Master of Theology at the South African Theological Seminary Supervisor: Professor Daniel Lioy Submitted on September 28, 2016 Table of Contents 1. Introduction: A Comparative Analysis of the Distinction between Law and Gospel in Gerhard Forde and Confessional Lutheranism. 1.1 Background 1.2 Problems and Objectives 1.3 Central Theoretical Argument and Purpose 1.4 Research Methodology 1.5 Conclusion 2. Literature Review 2.1 Introduction 2.2 The Confessional Lutheran Landscape 2.3 Writings from the Confessional Lutheran Tradition 2.3.1 David Scaer 2.3.2 Scott Murray 2.3.3 Joel Biermann 2.3.4 Joel Biermann and Charles Arand 2.3.5 Charles Arand 2.3.6 Jack Kilcrease 2.3.7 Confessional Lutheran Writers: Conclusion 2.4 Gerhard Forde 2.4.1 The Law-Gospel Debate 2.4.2 Where God Meets Man 2.4.3 The Writings of Gerhard Forde: Conclusion 2.5 Conclusion 2 | C o o p e r 3. The Scriptural and Theological Foundations for the Distinction Between Law and Gospel in Confessional Lutheranism 3.1 Introduction 3.2 Definition of the Law 3.3 Definition of the Gospel 3.4 Contrast and Continuity Between Law and Gospel 3.5 Law, Gospel, and the Atonement 3.6 The Third Use of the Law 3.7 The Scriptural Foundations of the Law-Gospel Distinction 3.8 The Practical Use of the Law-Gospel Paradigm 3.9 Conclusion 4. -

Marija Todorovska SOULS for SALE

99 ЗА ДУШАТА, Зборник, стр. 99-111, лето 2018 УДК: 2-167.64 : 128 прегледен труд Marija Todorovska PhD, Associate professor Institute for Philosophy, Faculty of Philosophy University Sts. Cyril and Methodius, Skopje SOULS FOR SALE: AN INTRODUCTION TO THE MOTIF OF BARGAINING WITH THE DARK SIDE Abstract The concept of a pact with some representative of the dark side persists in numerous cultural narratives and it almost always includes the steps of assumption of a soul, the possibility to trade it, and the risk/benefit ratio of doing so, a constant being the longing to gain superhu- man abilities and/or skills and successes. The motif of the soul-selling to dark, evil beings in terms of exchange of submission and servitude for earthly advantages and superhuman abil- ities and the promise of happiness in this life or the next is briefly examined, through some understandings of evil in the world (various instances of evil demons, devilish adversaries, Satan); along the need for exculpation for wrong-doing and the implications of free deci- sion-making; via the perception of the denouncement of the mainstream belief-systems and the contract with the Devil; and by pointing out some pact-with-the-Devil foundation stories. Keywords pact, devil, soul, Satan The concept of the contract between man and some representative of the im- agined forces of evil or darkness persists in a variety of stories for thousands of years and is usually about an exchange of the soul for extraordinary gains, with additional conditions depending on the characteristics of the parties involved, the period, the cultural climate and the dominant belief-system. -

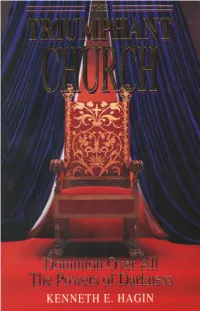

The Triumphant Church Are Constantly Ravaged by the Wiles of Satan and Are in a State of Continual Failure and Defeat

Kenneth E. Hagin Unless otherwise indicated, all Scripture quotations in this volume are from the King James Version of the Bible. Cover photograph of throne chair used by permission: Philbrook Museum of Art Tulsa, Oklahoma Fourth Printing 1994 ISBN 0-89276-520-8 In the U.S. Write: In Canada write: Kenneth Hagin Ministries Kenneth Hagin Ministries P.O. Box 50126 P.O. Box 335 Tulsa, OK 74150-0126 Etobicoke (Toronto), Ontario Canada, M9A 4X3 Copyright © 1993 RHEMA Bible Church AKA Kenneth Hagin Ministries, Inc. All Rights Reserved Printed The Faith Shield is a trademark of RHEMA Bible Church, AKA Kenneth Hagin Ministries, Inc., registered with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and therefore may not be duplicated. Contents 1 Origins: Satan and His Kingdom.................................5 2 Rightly Dividing Man: Spirit, Soul, and Body...........35 3 The Devil or the Flesh?...............................................69 4 Distinguishing the Difference Between Oppression, Obsession, and Possession...........................................107 5 Can a Christian Have a Demon?..............................143 6 How to Deal With Evil Spirits..................................173 7 The Wisdom of God...................................................211 8 Spiritual Warfare: Are You Wrestling or Resting?..253 9 Pulling Down Strongholds........................................297 10 Praying Scripturally to Thwart The Kingdom of Darkness.......................................................................329 11 Is the Deliverance Ministry Scriptural?.................369 12 Scriptural Ways to Minister Deliverance...............399 Chapter 1 1 Origins: Satan and His Kingdom Believers are seated with Christ in heavenly places, far above all powers and principalities of darkness. No demon can deter the believer who is seated with Christ far above all the works of the enemy! Our seating and reigning with Christ in heavenly places is a position of authority, honor, and triumph—not failure, depression, and defeat.