Faust Among the Witches: Towards an Ethics of Representation —David Hawkes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 18, 2018-No Deal with the Devil

Genesis 2:15-17; 3:1-13; Hebrews 4:14-16; Matthew 4:1-11 February 18, 2018 First Sunday in Lent Preached by Philip Gladden at the Wallace Presbyterian Church, Wallace, NC NO DEAL WITH THE DEVIL Let us pray: Let the words of my mouth and the meditation of my heart be acceptable to you, O Lord, our rock and our redeemer. Amen. Today at 2:00 p.m. the UNC-Wilmington theater department will present “Dr. Faustus.” The production will be set in a rock and roll dream world and is based on the 16th century play by Christopher Marlowe. The full title of the original play was “The Tragical History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus. Marlowe fashioned his play on old German folk tales about Doctor Faustus, an academic who made a deal with the devil, Lucifer, who is represented by the character Mephistophilis. Faustus gets bored with the regular academic subjects and trades his soul for twenty-four years of knowing and practicing the black arts and magic. Despite his misgivings about his deal with the devil as the end gets nearer, and frantic attempts to get out of the deal, Faustus is killed at the stroke of midnight.1 One legend says that when Doctor Faustus was first performed, actual devils showed up on stage and drove some audience members crazy. From that tragic story we get the phrase “a Faustian bargain.” This means trading in your values and morals, exchanging who you really are for some apparently awesome short-term goal. -

HIP HOP & Philosophy

Devil and Philosophy 2nd pages_HIP HOP & philosophy 4/8/14 10:43 AM Page 195 21 Souls for Sale JEFF EWING F Y O Selling your soul to the Devil in exchaPnge for a longer life, wealth, beauty, power, or skill has long been a theme in Obooks, movies, and even music. Souls have Obeen sold for Rknowledge and pleasure (Faust), eternal youth (Dorian Gray), the ability to play the guitar (Tommy JohnCson in O Brother, Where Art P Thou?) or the harmonica (Willie “Blind Do g Fulton Smoke House” Brown in the 1986 Emovie, Crossroads), or for rock’n’roll itself (the way Black SCabbath did on thDeir 1975 greatest hits album, We Sold Our Soul for Rock’n’ERoll). The selling of aN soul as an object of exchange for nearly any- thing, as a sort of fictitious comTmodity with nearly universal exchange valuAe, makes it perChaps the most unique of all possi- ble commVodities (and as such, contracts for the sales of souls are the most unique of aEll possible contracts). One theorist in partiDcular, Karl MaRrx (1818–1883), elaborately analyzed con- tracts, exchange, and “the commodity” itself, along with all the hAidden implicatRions of commodities and the exchange process. Let’s see what Marx has to tell us about the “political economy” of the FaustOian bargain with the Devil, and try to uncover what it trulyC is to sell your soul. N Malice and Malleus Maleficarum UWhile the term devil is sometimes used to refer to minor, lesser demons, in Western religions the term refers to Satan, the fallen angel who led a rebellion against God and was banished from Heaven. -

Joseph Smith and Diabolism in Early Mormonism 1815-1831

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2021 "He Beheld the Prince of Darkness": Joseph Smith and Diabolism in Early Mormonism 1815-1831 Steven R. Hepworth Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Hepworth, Steven R., ""He Beheld the Prince of Darkness": Joseph Smith and Diabolism in Early Mormonism 1815-1831" (2021). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 8062. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/8062 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "HE BEHELD THE PRINCE OF DARKNESS": JOSEPH SMITH AND DIABOLISM IN EARLY MORMONISM 1815-1831 by Steven R. Hepworth A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Approved: Patrick Mason, Ph.D. Kyle Bulthuis, Ph.D. Major Professor Committee Member Harrison Kleiner, Ph.D. D. Richard Cutler, Ph.D. Committee Member Interim Vice Provost of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2021 ii Copyright © 2021 Steven R. Hepworth All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT “He Beheld the Prince of Darkness”: Joseph Smith and Diabolism in Early Mormonism 1815-1831 by Steven R. Hepworth, Master of Arts Utah State University, 2021 Major Professor: Dr. Patrick Mason Department: History Joseph Smith published his first known recorded history in the preface to the 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon. -

"With His Blood He Wrote"

:LWK+LV%ORRG+H:URWH )XQFWLRQVRIWKH3DFW0RWLILQ)DXVWLDQ/LWHUDWXUH 2OH-RKDQ+ROJHUQHV Thesis for the degree of philosophiae doctor (PhD) at the University of Bergen 'DWHRIGHIHQFH0D\ © Copyright Ole Johan Holgernes The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Year: 2017 Title: “With his Blood he Wrote”. Functions of the Pact Motif in Faustian Literature. Author: Ole Johan Holgernes Print: AiT Bjerch AS / University of Bergen 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following for their respective roles in the creation of this doctoral dissertation: Professor Anders Kristian Strand, my supervisor, who has guided this study from its initial stages to final product with a combination of encouraging friendliness, uncompromising severity and dedicated thoroughness. Professor Emeritus Frank Baron from the University of Kansas, who encouraged me and engaged in inspiring discussion regarding his own extensive Faustbook research. Eve Rosenhaft and Helga Muellneritsch from the University of Liverpool, who have provided erudite insights on recent theories of materiality of writing, sign and indexicality. Doctor Julian Reidy from the Mann archives in Zürich, with apologies for my criticism of some of his work, for sharing his insights into the overall structure of Thomas Mann’s Doktor Faustus, and for providing me with some sources that have been valuable to my work. Professor Erik Bjerck Hagen for help with updated Ibsen research, and for organizing the research group “History, Reception, Rhetoric”, which has provided a platform for presentations of works in progress. Professor Lars Sætre for his role in organizing the research school TBLR, for arranging a master class during the final phase of my work, and for friendly words of encouragement. -

They Sold Their Soul to the Devil Have You Noticed the Number of Hollywood and Music Industry Stars Claiming to Have Sold Their

They Sold Their Soul to the Devil Have you noticed the number of Hollywood and music industry stars claiming to have sold their souls to the devil? Souled out stars. •“Sold my soul, from heaven into hell.” - 30 Seconds to Mars •“Sell his soul for cheap. Let’s make a deal, sell me your soul. Designer of the devil.” - 50 Cent •“I sold my soul to the devil in L.A” - Aaron Lewis •“Some sell their soul for the easy road. The devil’s always buying. I can’t count the ones I’ve known who fell right into line.” - Aaron Tippin •“‘I sold my soul to the devil.” - Abi Titmuss •“I’m just a demon that means well. Freelance for God, but do the work of Satan.” - Ab- Soul •“Hey Satan, pay my dues. I’m gonna take you to hell, I’m gonna get ya Satan.” - AC/DC •“There’s plenty of money to be had. But you also lose your soul.” - Alan Alda •“And tempt the soul of any man. Between the devil and me. The gates of hell swing open.” - Alan Jackson •“Dr. Dre told me he sold his soul to the devil for a million bucks.” - Alonzo Williams •“The dark covers me and I cannot run now.” - Amy Winehouse •“I sold my soul.” - Andrew W.K. •“But when it comes time to decide your fate, they’ll sign you on the line right next to Satan. Cause’ they don’t care about us. They just use us up.” - Asher Roth •“I sold my soul to the devil.” - Aubrey Plaza •“Dance with the devil. -

Marija Todorovska SOULS for SALE

99 ЗА ДУШАТА, Зборник, стр. 99-111, лето 2018 УДК: 2-167.64 : 128 прегледен труд Marija Todorovska PhD, Associate professor Institute for Philosophy, Faculty of Philosophy University Sts. Cyril and Methodius, Skopje SOULS FOR SALE: AN INTRODUCTION TO THE MOTIF OF BARGAINING WITH THE DARK SIDE Abstract The concept of a pact with some representative of the dark side persists in numerous cultural narratives and it almost always includes the steps of assumption of a soul, the possibility to trade it, and the risk/benefit ratio of doing so, a constant being the longing to gain superhu- man abilities and/or skills and successes. The motif of the soul-selling to dark, evil beings in terms of exchange of submission and servitude for earthly advantages and superhuman abil- ities and the promise of happiness in this life or the next is briefly examined, through some understandings of evil in the world (various instances of evil demons, devilish adversaries, Satan); along the need for exculpation for wrong-doing and the implications of free deci- sion-making; via the perception of the denouncement of the mainstream belief-systems and the contract with the Devil; and by pointing out some pact-with-the-Devil foundation stories. Keywords pact, devil, soul, Satan The concept of the contract between man and some representative of the im- agined forces of evil or darkness persists in a variety of stories for thousands of years and is usually about an exchange of the soul for extraordinary gains, with additional conditions depending on the characteristics of the parties involved, the period, the cultural climate and the dominant belief-system. -

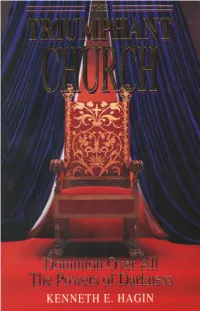

The Triumphant Church Are Constantly Ravaged by the Wiles of Satan and Are in a State of Continual Failure and Defeat

Kenneth E. Hagin Unless otherwise indicated, all Scripture quotations in this volume are from the King James Version of the Bible. Cover photograph of throne chair used by permission: Philbrook Museum of Art Tulsa, Oklahoma Fourth Printing 1994 ISBN 0-89276-520-8 In the U.S. Write: In Canada write: Kenneth Hagin Ministries Kenneth Hagin Ministries P.O. Box 50126 P.O. Box 335 Tulsa, OK 74150-0126 Etobicoke (Toronto), Ontario Canada, M9A 4X3 Copyright © 1993 RHEMA Bible Church AKA Kenneth Hagin Ministries, Inc. All Rights Reserved Printed The Faith Shield is a trademark of RHEMA Bible Church, AKA Kenneth Hagin Ministries, Inc., registered with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and therefore may not be duplicated. Contents 1 Origins: Satan and His Kingdom.................................5 2 Rightly Dividing Man: Spirit, Soul, and Body...........35 3 The Devil or the Flesh?...............................................69 4 Distinguishing the Difference Between Oppression, Obsession, and Possession...........................................107 5 Can a Christian Have a Demon?..............................143 6 How to Deal With Evil Spirits..................................173 7 The Wisdom of God...................................................211 8 Spiritual Warfare: Are You Wrestling or Resting?..253 9 Pulling Down Strongholds........................................297 10 Praying Scripturally to Thwart The Kingdom of Darkness.......................................................................329 11 Is the Deliverance Ministry Scriptural?.................369 12 Scriptural Ways to Minister Deliverance...............399 Chapter 1 1 Origins: Satan and His Kingdom Believers are seated with Christ in heavenly places, far above all powers and principalities of darkness. No demon can deter the believer who is seated with Christ far above all the works of the enemy! Our seating and reigning with Christ in heavenly places is a position of authority, honor, and triumph—not failure, depression, and defeat. -

From the Crucible by Arthur Miller

from The Crucible By Arthur Miller INTO THE PLAY The Crucible is based on real events that took place in Salem, Massachusetts, in 1692. As the play begins, the author provides some background information about the setting, the characters, and their mindsets, before the characters start to speak. The author also draws some comparisons between the events in Salem and the events of the 1950s, when he was writing this play. ACT ONE 1 A HERE’S HOW (An Overture ) Reading Focus A small upper bedroom in the home of !"#"!"$% &'()"* +'!!,&, As I begin to read, I want to draw conclusions about the Salem, Massachusetts, in the spring of the year 1692. A characters’ motivations, or reasons, for what they do. I There is a narrow window at the left. Through its leaded already know what Samuel Parris does for a living, where panes the morning sunlight streams. A candle still burns near the he lives, and what time period bed, which is at the right. A chest, a chair, and a small table are he is from. From the start, I can draw the conclusion the other furnishings. At the back a door opens on the landing of that Reverend Parris might want to maintain a good the stairway to the ground floor. The room gives off an air of clean reputation in his community. spareness.2 The roof rafters are exposed, and the wood colors are I will watch to see if this is a 3 true motivation for Parris. 10 raw and unmellowed. As the curtain rises, !"#"!"$% +'!!,& is discovered kneeling B HERE’S HOW beside the bed, evidently in prayer. -

The Faustus Myth in the English Novel

The Faustus Myth in the English Novel The Faustus Myth in the English Novel By Şeyda Sivrioğlu The Faustus Myth in the English Novel By Şeyda Sivrioğlu This book first published 2017 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2017 by Şeyda Sivrioğlu All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-8284-4 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-8284-2 CONTENTS List of Illustrations .................................................................................... vii Abstract ...................................................................................................... ix Preface ........................................................................................................ xi Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Chapter One ............................................................................................... 17 The Beginning of the Faustus Myth 1.1 The Historical Faustus ................................................................... 18 1.2 The First Human Curiosity ............................................................ 26 1.3 The Theory -

Kenneth E Hagin

Hie Origin and Operation of DEMONS Volume 1 of the Satan, Demons, and Demon Possession Series By Kenneth E. Hagin Second Edition First Printing 1983 ISBN 0-89276-025-7 In the U.S. write: In Canada write: Kenneth Hagin Ministries Kenneth Hagin Ministries P.O. Box 50126 P.O. Box 335 Tulsa, Oklahoma 74150 Islington (Toronto), Ontario Canada, M9A 4X3 Copyright ft; 1983 RHEMA Bible Church AKA Kenneth Hagin Ministries, Inc. All Kights Reserved Printed in USA Contents Foreword 1. The Origin of Demons ............ 1 2. The Operation of Demons ...... 12 The Satan, Demons, and Demon Possession Series: Volume 1 — The Origin and Operation of Demons Volume 2 — Demons and How To Deal With Them Volume 3 — Ministering to the Oppressed Volume 4 — Bible Answers to Man's Questions on Demons Foreword The Book of Revelation teaches us, ".. .for the devil is come down unto you, having great wrath, because he knoweth that he hath but a short time" (Rev. 12:12). This is the reason there is such an increase of demon activity the world around. The devil knows his time is short. Yet, though demon activity has increased, knowledge in spiritual matters has increased. The Spirit of God said to me concerning this: "There is coming what men call a breakthrough. In the spiritual realm it existed all the time. But in the natural realm a breakthrough is coming in the area of the spirit world and spirit activity — demonology, if you would like to call it that. "Also, a breakthrough is coming in the realm of spirits concerning angels — for they are spirits. -

The History of Western Demonology and Its Role in the Contemporary Nature-Technology Debate

AS ORIGENS DO PENSAMENTO OCIDENTAL THE ORIGINS OF WESTERN THOUGHT ARTIGO I ARTICLE The Demon of Technology: The History of Western Demonology and its role in the contemporary nature-technology debate Enrico Postiglione i https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5935-424X [email protected] i University of Modena and Reggio Emilia – Reggio Emilia – Italy POSTIGLIONE, E. (2020). The Demon of Technology: The History of Western Demonology and its role in the contemporary nature-technology debate. Archai 29, e02902. Abstract: Contemporary advanced technology seems to raise new and fundamental questions as it apparently provides a human subject with an infinite range of incoming possibilities. Accordingly, research on the implications of technology is massive and splits into hard critics and faithful supporters. Yet, technological activities https://doi.org/10.14195/1984-249X_29_2 [1] 2 Rev. Archai (ISSN: 1984-249X), n. 29, Brasília, 2020, e02902. cannot be defined in terms of their products alone. Indeed, every technological behaviour unfolds the very same tension against what would have been naturally impossible, in absence of that same behaviour. Thus, the debate on technology appears to be independent from any level of technological sophistication, and so its roots can be traced back in the dawn of Western thought. In this article, I argue that the faithful and sceptic views today at stake on hard-technology can be explained as a revival of the twofold attitude towards demons, developed in the history of Western thought. I show how demons have always embodied the human natural limits and the incomprehensible aspects of reality. Exactly as in the case of demons, hard-technology is now seen as a fearful destroyer of both nature understood as a complex system and human naturalness or as a trustful way to save humanity from decay, which complements what is naturally imperfect and, then, perfectible. -

The Witch Hunt - and Why It Is Still Misunderstood and Important at the Same Time Deutsche Version Hier Und Hier

The Witch Hunt - and why it is still misunderstood and important at the same time deutsche Version hier und hier The Witch Hunt - and why it is still misunderstood and important at the same time 'For 50 years I have never read a book that suchlike hits the nerve of our occidental culture'. It is unfortunate that this outstanding work is only available antiquarian. Or should I say it is indicative of the spirit of the present?' Who persecuted the Witch-Midwives? And why? Or How the anti-sexual morality in Europe was established by Ottmar Lattorf The article was already published in October 1997 in the Berlin Journal 'emotion' (contributions to the work of Wilhelm Reich, Knapp Diederichs, No. 12/13. The publisher was Volker Lubminer Pfad 20, 13502 Berlin. Tel. 030/43 67 30 89. The issue had the ISDN number 0720-0579. Here is the revised and supplemented text in public domain 1 The Witch Hunt - and why it is still misunderstood and important at the same time I would like to thank Prof. Bernd Senf from the University of Applied Sciences in Berlin, who had invited me for 10 years to the topic of Witch Hunt to the University of Economics and Law Berlin during his lectures on the works of Wilhelm Reich. The publisher of this brochure is the author himself: Ottmar Lattorf, Mannsfelder Strasse 17, 50968 Cologne. Telephone: 0221/34 11 82 Design by Ottmar Lattorf. The cover picture is (on the bottom, depicts) a woodcut by Gustav Dore titled 'La danse du Sabbat'.