Frontiersmen Are the “Real Men” I FRONTIERSMEN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

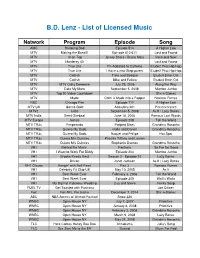

B.D. Lenz - List of Licensed Music

B.D. Lenz - List of Licensed Music Network Program Episode Song AMC Breaking Bad Episode 514 A Higher Law MTV Making the Band II Episode 610 611 Lost and Found MTV 10 on Top Jersey Shore / Bruno Mars Here and Now MTV Monterey 40 Lost and Found MTV True Life I'm Addicted to Caffeine Etude2 Phat Hip Hop MTV True Life I Have a new Step-parent Etude2 Phat Hip Hop MTV Catfish Trina and Scorpio Etude4 Bmin Ost MTV Catfish Mike and Felicia Etude4 Bmin Ost MTV MTV Oshq Deewane July 29, 2006 Along the Way MTV Date My Mom September 5, 2008 Mumbo Jumbo MTV Top 20 Video Countdown Stix-n-Stones MTV Made Colin is Made into a Rapper Noxious Fumes NBC Chicago Fire Episode 711 A Higher Law MTV UK Gonzo Gold Acoustics 201 Perserverance MTV2 Cribs September 5, 2008 As If / Lazy Bones MTV India Semi Girebaal June 18, 2006 Famous Last Words MTV Europe Gonzo Episode 208 Tell the World MTV TR3s Pimpeando Pimped Bikes Grandma Rosocha MTV TR3s Quiero My Boda Halle and Daneil Grandma Rosocha MTV TR3s Quiero My Boda Raquel and Philipe Hot Spot MTV TR3s Quiero Mis Quinces Priscilla Tiffany and Lauren MTV TR3s Quiero Mis Quinces Stephanie Duenas Grandma Rosocha VH1 Behind the Music Fantasia So Far So Good VH1 I Want to Work For Diddy Episode 204 Mumbo Jumbo VH1 Brooke Knows Best Season 2 - Episode 10 Lazy Bones VH1 Driven Janet Jackson As If / Lazy Bones VH1 Classic Hangin' with Neil Peart Part 3 Noxious Fumes VH1 Celebrity Fit Club UK May 10, 2005 As If VH1 Best Week Ever February 3, 2006 Tell the World VH1 Best Week Ever Episode 309 Walt's Waltz VH1 My Big Fat -

Michelle Bench Avid Editor

Michelle Bench Avid Editor Profile Michelle is a passionate editor and her technical knowledge is first-class - she has a thorough understanding of all aspects of the editing process. She was previously employed by facilities house M2 where she capably worked on some of their highest profile programmes and with the most demanding of clients. She has a natural talent in constructing and helping develop narratives. Michelle is incredibly hardworking and enthusiastic and along with her easy going friendly personality, she is a real asset to a production. Offline Credits – Entertainment “Pioneer Woman” 9 x 30min. Top rating cooking, documentary and reality series shot on a ranch in Pawhuska, Oklahoma with blogger Ree Drummond and her family. Otherwise known as the 'Pioneer Woman', Ree is a mother, wife and cook. The award-winning blogger and best-selling cookbook author comes to Food Network and shares her special brand of home cooking, from throw together suppers to elegant celebrations. Pacific Productions for Food Network “Barefoot Contessa” Ina Garten prepares a simple multi-course meal, usually for her close friends, colleagues or husband. Her recipes often include fresh herbs, which she 'hand- harvests' from her backyard garden. The show's title comes from the Italian word for countess and was originally used by Ina Garten in her best-selling cookbook. Pacific Productions for Food Network “13 Moments that Killed Michael Jackson” 1 x 90min. 3 part documentary series. This takes a look at the extraordinary life, and tragic death, of one of the world’s best loved entertainers. Counting down the fateful episodes that changed his life, this programme will explore the heartache behind the triumph, and the lows behind the highs in the life of a music icon. -

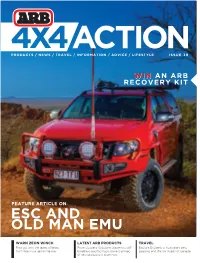

ESC and Old Man Emu

AI CT ON PRODUCTS / NEWS / TRAVEL / INFORMATION / ADVICE / LIFESTYLE ISS9 UE 3 W IN AN ARB RECOVERY KIT FEATURE ARTICLE ON ESC AND OLD MAN EMU WARN ZEON WINCH LATEST ARB PRODUCTS TRAVEL Find out why the latest offering From Outback Solutions drawers to diff Explore El Questro, Australia’s best from Warn is a game changer breathers and flip flops, there is a heap beaches and the Ice Roads of Canada of new products in store now CONTENTS PRODUCTS COMPETITIONS & PROMOTIONS 4 ARB Intensity LED Driving Light Covers 5 Win An ARB Back Pack 16 Old Man Emu & ESC Compatibility 12 ARB Roof Rack With Free 23 ARB Differential Breather Kit Awning Promotion 26 ARB Deluxe Bull Bar for Jeep WK2 24 Win an ARB Recovery Kit Grand Cherokee 83 On The Track Photo Competition 27 ARB Full Extension Fridge Slide 32 Warn Zeon Winch 44 Redarc In-Vehicle Chargers 45 ARB Cab Roof Racks For Isuzu D-Max REGULARS & Holden Colorado 52 Outback Solutions Drawers 14 Driving Tips & Techniques 54 Latest Hayman Reese Products 21 Subscribe To ARB 60 Tyrepliers 46 ARB Kids 61 Bushranger Max Air III Compressor 50 Behind The Shot 66 Latest Thule Accessories 62 Photography How To 74 Hema HN7 Navigator 82 ARB 24V Twin Motor Portable Compressor ARB 4X4 ACTION Is AlsO AvAIlABlE As A TRAVEL & EVENTS FREE APP ON YOUR IPAD OR ANDROID TABLET. 6 Life’s A Beach, QLD BACk IssuEs CAN AlsO BE 25 Rough Stuff, Australia dOwNlOAdEd fOR fREE. 28 Ice Road, Canada 38 Water For Africa, Tanzania 56 The Eastern Kimberley, WA Editor: Kelly Teitzel 68 Emigrant Trail, USA Contributors: Andrew Bellamy, Sam Boden, Pat Callinan, Cassandra Carbone, Chris Collard, Ken Duncan, Michael Ellem, Steve Fraser, Matt 76 ARB Eldee Easter 4WD Event, NSW Frost, Rebecca Goulding, Ron Moon, Viv Moon, Mark de Prinse, Carlisle 78 Gunbarrel Hwy, WA Rogers, Steve Sampson, Luke Watson, Jessica Vigar. -

Magnolia- Spring 2002

Magnolia Bulletin of the Magnolia grandiflora Southern Garden The Laurel Tree of Carolina Catesby’s Natural History, 1743 History Society Vol. XVII No. 3 Spring 2002 Gardening with Mrs. Balfour: An Antebellum Vicksburg Gardener By John Sykes, Baton Rouge, Louisiana clan on the Walnut Hills near the confluence of the n May 1853 Emma Balfour wrote her sister-in- Yazoo and the Mississippi Rivers.3 The commanding I law: “I wish you could see my garden location was the site of an early Spanish fort. now. It is really beautiful. The Some two hundred feet above the high roses are as fine as they can well be & I water mark of the river, the rolling hills have such a variety of other flowers presented an incredible vista across that the whole garden as one miles of flat delta land sweeping looks at it from the gallery West and North. A 19th- above or from the street looks century visitor commented on like a mass of flowers. It is the unusual geography: so complimented that I “There [is] only one way to begin to feel very account for the hills of proud.” 1 Throughout Vicksburg — after the the 1850s, Emma Lord of Creation had Harrison Balfour made all the big pursued her passion for mountains and ranges of gardening at her new hills, He had left on His home in Vicksburg, hands a large lot of Mississippi. For her scraps; these were all garden Emma Balfour dumped at Vicksburg . conducted an extensive ”4 The entrepreneurial search for plants from Parson Vick envisioned a friends, local nurseries town on the hills and and those available down managed to sell a lot before river from New Orleans. -

Televisionweek Local Listing for the Week of August 29-September 4, 2015

PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, AUGUST 28, 2015 PAGE 9B TelevisionWeek Local Listing For The Week Of August 29-September 4, 2015 SATURDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT AUGUST 29, 2015 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS America’s Victory Prairie America’s Classic Gospel “At- The Lawrence Welk Doc Martin “The Keeping As Time Father Brown Violet No Cover, No Mini- Austin City Limits Front and Center Brit- Globe Trekker Influ- PBS Test Garden’s Yard and Heartlnd lanta Homecoming” Show “You’re Never Admirer” Louisa has a Up Goes hopes to prove her in- mum “Jami Lynn” The Avett Brothers and ish songwriter Richard ence of Sicilian cuisine. KUSD ^ 8 ^ Kitchen Garden Inspirational songs. Too Young” rival. Å By Å nocence. Å Nickel Creek. Thompson. (In Stereo) KTIV $ 4 $ Horse Racing Estate News News 4 Insider American Ninja Warrior “Military Finals” Hannibal (In Stereo) News 4 Saturday Night Live Å Extra (N) Å 1st Look House Horse Racing Travers Stakes and Sword Paid Pro- NBC KDLT The Big American Ninja Warrior “Military Finals” Hannibal Will hopes to KDLT Saturday Night Live Taraji P. The Simp- NBC Pri- KDLT (Off Air) NBC Dancer Invitational. From Saratoga Race gram Nightly News Bang Obstacles include Doorknob Arch. (In Stereo) slay Francis Dolarhyde. News Henson; Mumford & Sons. (In sons metime News Å KDLT % 5 % Course in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. -

Ice Road Truckers Needn't Fret

Western Canada’s Trucking Newspaper Since 1989 December 2016 Volume 27, Issue 12 Rock slide: B.C. rock slide Helping truckers: Truckers STA gala: Saskatchewan RETAIL wipes out section of Trans- Christmas Group looks for Trucking Association holds ADVERTISING Canada Highway, costs donations to help trucking annual gala, addresses Page 13 Page 16 Page Page 12 Page industry thousands. families. industry issues. PAGES 29-39 truckwest.ca Safety on winter roads Winter driving conditions can pose challenge to even the biggest rig By Derek Clouthier Many believe that the use of airships, like the one depicted above, to deliver cargo to Canada’s northern region would bring REGINA, Sask. – Don’t be fooled by the business to the trucking industry. balmy mid-November temperatures that hit Western Canada this year – win- ter is just around the corner. And whether you’re trucking through mountainous terrain in British Colum- bia or making your way across the prai- Ice road truckers ries of Saskatchewan, slippery roads and reduced visibility can wreak havoc. The Saskatchewan Ministry of High- ways and Infrastructure urge truck Reach us at drivers to conduct thorough trip in- our Western needn’t fret spections, and to give extra time dur- Canada news ing the winter months to complete. bureau “Checking your truck, trailer(s), tires, brakes, lights and other equipment be- Contact How the use of airships would fore you start a trip is always impor- Derek Clouthier tant,” the ministry informed Truck Derek@ West. “With cold weather, extra care should be taken with these regular in- Newcom.ca help the trucking industry spections. -

Cablefax Program Awards 2021 Winners and Nominees

March 31, 2021 SPECIAL ISSUE CFX Program Awards Honoring the 2021 Nominees & Winners PROGRAM AWARDS March 31, 2021 The Cablefax Program Awards has a long tradition of honoring the best programming in a particular content niche, regardless of where the content originated or how consumers watch it. We’ve recognized breakout shows, such as “Schitt’s Creek,” “Mad Men” and “RuPaul’s Drag Race,” long before those other award programs caught up. In this special issue, we reveal our picks for best programming in 2020 and introduce some special categories related to the pandemic. Read all about it! As an interactive bonus, the photos with red borders have embedded links, so click on the winner photos to sample the program. — Amy Maclean, Editorial Director Best Overall Content by Genre Comedy African American Winner: The Conners — ABC Entertainment Winner: Walk Against Fear: James Meredith — Smithsonian Channel This timely documentary is named after James Meredith’s 1966 Walk Against Fear, in which he set out to show a Black man could walk peace- fully in Mississippi. He was shot on the second day. What really sets this The Conners shines at finding ways to make you laugh through life’s film apart is archival footage coupled with a rare one-on-one interview with struggles, whether it’s financial pressures, parenthood, or, most recently, the Meredith, the first Black man to enroll at the University of Mississippi. pandemic. You could forgive a sitcom for skipping COVID-19 in its storyline, but by tackling it, The Conners shows us once again that life is messy and Nominees sometimes hard, but with love and humor, we persevere. -

Texas Military Preparedness Commission Biennial Report Table of Contents

Texas Military Preparedness Commission Biennial Report Table of Contents 2 Letter to the Governor 3 Executive Summary 4 The Defense Economy and Texas Highlights 6 The Commission Mission & Strategies Commissioners Ex-Officio Members Staff & Interns Funding Programs, Texas Military Value Revolving Loan Fund (TMVRLF) Funding Programs, Defense Economic Adjustment Assistance Grant (DEAAG) Texas Military Value Task Force (TMVTF) Governor’s Committee to Support the Military (GCSM) 16 Texas Commander’s Council, Recommendations 18 State Defense Legislation 21 Military Installations in Texas: Overview and Economic Impact 22 Economic Impact: Methodology and Disclaimers 24 Economic Impact Map 25 U.S. Air Force Installations Dyess Air Force Base Goodfellow Air Force Base Laughlin Air Force Base Sheppard Air Force Base 34 U.S. Army Installations & Army Futures Command Corpus Christi Army Depot Fort Bliss Fort Hood Red River Army Depot Army Futures Command 45 U.S. Navy Installations Naval Air Station Corpus Christi Naval Air Station Joint Reserve Base Fort Worth Naval Air Station Kingsville 52 Joint Base San Antonio & Ellington Field Joint Reserve Base 57 Texas Military Forces Air National Guard Army National Guard Texas State Guard 62 Resources: Wind Energy and Military Operations 64 Resources: Maps Cover photo courtesy of U.S. Army/ By Capt. Roxana Thompson 1 Letter to the Governor Dear Governor Abbott: On behalf of the Texas Military Preparedness Commission (TMPC), I am pleased to submit to you the 2019-2020 TMPC Biennial Report. It has been an eventful two years since our last biennial report to you. The military continues to grow in their missions as Texas seeks opportunities to continue being the best home to military personnel in the nation. -

Honey Boo Boo, Tumblr, and the Stereotype of Poor White Trash Ashley F

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 12-14-2015 Redneckaissance: Honey Boo Boo, Tumblr, and the Stereotype of Poor White Trash Ashley F. Miller University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Miller, A. F.(2015). Redneckaissance: Honey Boo Boo, Tumblr, and the Stereotype of Poor White Trash. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3217 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REDNECKAISSANCE: HONEY BOO BOO, TUMBLR, AND THE STEREOTYPE OF POOR WHITE TRASH by Ashley F. Miller Bachelor of Arts Emory University, 2006 Master of Fine Arts Florida State University, 2008 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Mass Communications College of Information and Communications University of South Carolina 2015 Accepted by: August Grant, Major Professor Carol Pardun, Committee Member Leigh Moscowitz, Committee Member Lynn Weber, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Senior Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Ashley F. Miller, 2015 All Rights Reserved. ii Acknowledgements Although her name is not among the committee members, this study owes a great deal to the extensive help of Kathy Forde. It could not have been done without her. Thanks go to my mother and fiancé for helping me survive the process, and special thanks go to L. Nicol Cabe for ensuring my inescapable relationship with the Internet and pop culture. -

On Reality Television During the Great Recession

Societies 2012, 2, 235–251; doi:10.3390/soc2040235 OPEN ACCESS societies ISSN 2075-4698 www.mdpi.com/journal/societies Article Working Stiff(s) on Reality Television during the Great Recession Sean Brayton Department of Kinesiology and Physical Education, University of Lethbridge, 4401 University Drive, Lethbridge, AB, T1K 3M4, Canada; E-Mail: [email protected] Received: 6 August 2012; in revised form: 22 October 2012 / Accepted: 23 October 2012 / Published: 29 October 2012 Abstract: This essay traces some of the narratives and cultural politics of work on reality television after the economic crash of 2008. Specifically, it discusses the emergence of paid labor shows like Ax Men, Black Gold and Coal and a resurgent interest in working bodies at a time when the working class in the US seems all but consigned to the dustbin of history. As an implicit response to the crisis of masculinity during the Great Recession these programs present an imagined revival of manliness through the valorization of muscle work, which can be read in dialectical ways that pivot around the white male body in peril. In Ax Men, Black Gold and Coal, we find not only the return of labor but, moreover, the re-embodiment of value as loggers, roughnecks and miners risk both life and limb to reach company quotas. Paid labor shows, in other words, present a complicated popular pedagogy of late capitalism and the body, one that relies on anachronistic narratives of white masculinity in the workplace to provide an acute critique of expendability of the body and the hardships of physical labor. -

06 4-15 TV Guide.Indd 1 4/15/08 7:49:32 AM

PAGE 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2008 Monday Evening April 21, 2008 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With the Stars Samantha Bachelor-Lond Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY , APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS Big Bang How I Met Two Men Rules CSI: Miami Local Late Show-Letterman Late Late KSNK/NBC Deal or No Deal Medium Local Tonight Show Late FOX Bones House Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Intervention I Survived Crime 360 Intervention AMC Ferris Bueller Teen Wolf StirCrazy ANIM Petfinder Animal Cops Houston Animal Precinct Petfinder Animal Cops Houston CNN CNN Election Center Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Dirty Jobs Dirty Jobs Verminators How-Made How-Made Dirty Jobs DISN Finding Nemo So Raven Life With The Suite Montana Replace Kim E! Keep Up Keep Up True Hollywood Story Girls Girls E! News Chelsea Daily 10 Girls ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Fastbreak Baseball Norton TV ESPN2 Arena Football Football E:60 NASCAR Now FAM Greek America's Prom Queen Funniest Home Videos The 700 Club America's Prom Queen FX American History X '70s Show The Riches One Hour Photo HGTV To Sell Curb Potential Potential House House Buy Me Sleep To Sell Curb HIST Modern Marvels Underworld Ancient Discoveries Decoding the Past Modern Marvels LIFE Reba Reba Black and Blue Will Will The Big Match MTV True Life The Paper The Hills The Hills The Paper The Hills The Paper The Real World NICK SpongeBob Drake Home Imp. -

George W Bush Childhood Home Reconnaissance Survey.Pdf

Intermountain Region National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior August 2015 GEORGE W. BUSH CHILDHOOD HOME Reconnaissance Survey Midland, Texas Front cover: President George W. Bush and First Lady Laura Bush speak to the media after touring the President’s childhood home at 1421 West Ohio Avenue, Midland, Texas, on October 4, 2008. President Bush traveled to attend a Republican fundraiser in the town where he grew up. Photo: SAUL LOEB/AFP/Getty Images CONTENTS BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE — i SUMMARY OF FINDINGS — iii RECONNAISSANCE SURVEY PROCESS — v NPS CRITERIA FOR EVALUATION OF NATIONAL SIGNIFICANCE — vii National Historic Landmark Criterion 2 – viii NPS Theme Studies on Presidential Sites – ix GEORGE W. BUSH: A CHILDHOOD IN MIDLAND — 1 SUITABILITY — 17 Childhood Homes of George W. Bush – 18 Adult Homes of George W. Bush – 24 Preliminary Determination of Suitability – 27 HISTORY AND DESCRIPTION OF THE GEORGE W. BUSH CHILDHOOD HOME, MIDLAND TEXAS — 29 Architectural Description – 29 Building History – 33 FEASABILITY AND NEED FOR NPS MANAGEMENT — 35 Preliminary Determination of Feasability – 37 Preliminary Determination of Need for NPS Management – 37 CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS — 39 APPENDIX: THE 41ST AND 43RD PRESIDENTS AND FIRST LADIES OF THE UNITED STATES — 43 George H.W. Bush – 43 Barbara Pierce Bush – 44 George W. Bush – 45 Laura Welch Bush – 47 BIBLIOGRAPHY — 49 SURVEY TEAM MEMBERS — 51 George W. Bush Childhood Home Reconnaissance Survey George W. Bush’s childhood bedroom at the George W. Bush Childhood Home museum at 1421 West Ohio Avenue, Midland, Texas, 2012. The knotty-pine-paneled bedroom has been restored to appear as it did during the time that the Bush family lived in the home, from 1951 to 1955.