On Reality Television During the Great Recession

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

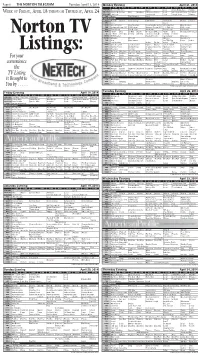

06 4-15-14 TV Guide.Indd

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2014 Monday Evening April 21, 2014 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With Stars Castle Local Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline WEEK OF FRIDAY, APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY, APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS 2 Broke G Friends Mike Big Bang NCIS: Los Angeles Local Late Show Letterman Ferguson KSNK/NBC The Voice The Blacklist Local Tonight Show Meyers FOX Bones The Following Local Cable Channels A&E Duck D. Duck D. Duck Dynasty Bates Motel Bates Motel Duck D. Duck D. AMC Jaws Jaws 2 ANIM River Monsters River Monsters Rocky Bounty Hunters River Monsters River Monsters CNN Anderson Cooper 360 CNN Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 E. B. OutFront CNN Tonight DISC Fast N' Loud Fast N' Loud Car Hoards Fast N' Loud Car Hoards DISN I Didn't Dog Liv-Mad. Austin Good Luck Win, Lose Austin Dog Good Luck Good Luck E! E! News The Fabul Chrisley Chrisley Secret Societies Of Chelsea E! News Norton TV ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Olbermann ESPN2 NFL Live 30 for 30 NFL Live SportsCenter FAM Hop Who Framed The 700 Club Prince Prince FX Step Brothers Archer Archer Archer Tomcats HGTV Love It or List It Love It or List It Hunters Hunters Love It or List It Love It or List It HIST Swamp People Swamp People Down East Dickering America's Book Swamp People LIFE Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Listings: MTV Girl Code Girl Code 16 and Pregnant 16 and Pregnant House of Food 16 and Pregnant NICK Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Friends Friends Friends SCI Metal Metal Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Metal Metal For your SPIKE Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Jail Jail TBS Fam. -

06 10-26-10 TV Guide.Indd 1 10/26/10 8:08:17 AM

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, October 26, 2010 Monday Evening November 1, 2010 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With Stars Castle Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , OCT . 29 THROUGH THURSDAY , NOV . 4 KBSH/CBS How I Met Rules Two Men Mike Hawaii Five-0 Local Late Show Letterman Late KSNK/NBC Chuck The Women of SNL Local Tonight Show w/Leno Late FOX MLB Baseball Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Hoarders Hoarders Intervention Intervention AMC Red Planet Rubicon Mad Men Volcano ANIM Pit Bulls-Parole Pit Bulls-Parole River Monsters Pit Bulls-Parole Pit Bulls-Parole CNN Parker Spitzer Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Wreck Wreck American Chopper American Chopper Wreck Wreck American Chopper DISN Den Brother Deck Hannah Hannah Deck Deck Hannah Hannah E! Kardashian True Hollywood Story Fashion Soup Pres Chelsea E! News Chelsea Norton TV ESPN Countdown NFL Football SportsCenter ESPN2 2010 Poker 2010 Poker 2010 Poker E:60 SportsNation FAM Funniest Home Videos Funniest Home Videos Funniest Home Videos The 700 Club My Wife My Wife FX Spider-Man 3 Two Men Two Men Malcolm HGTV Property First House Designed House Hunters My First My First House Designed HIST Pawn Pawn American American Pawn Pawn Ancient Aliens Pawn Pawn LIFE Reba Reba Lying to Be Perfect How I Met How I Met The Fairy Jobmother Listings: MTV Jersey Shore World World World Buried World Buried Jersey Shore NICK My Wife My Wife Chris Chris Lopez Lopez The Nanny The Nanny The Nanny The Nanny SCI Scare Scare Scare Scare Scare Scare Gundam Gundam Darkness Darkness For your SPIKE Star Wars-Phantom Star Wars-Phantom Disorderly Con. -

Today's Television

54 TV TUESDAY DECEMBER 29 2020 Start the day Zits Insanity Streak lHAD~UCflA UNFORTUNATE::!.'(, t;HE: with a laugh TIMr;;:AT!-UN OL-DME'1VUR ... OW NoTM1NG MUCM, How are dogs like cell JUST $OCllL 1>1STlNC1NG ,.. phones? 1>.NI> YoO? They both have collar id. wHaT kind of key can never unlock a door? A monkey. Snake Tales Swamp I OON'"r -.HIN< -rHl:S Today’s quiz IS GOING "l"O SE. .. 1. is a monteith a type of bowl, cape or curtain? 291220 2. The tangelo is a hybrid of which two fruits? f fq()J/ 3. What is a farthingale? T oday’S TeleViSion 4. Which country is the nine SeVen abc SbS Ten world’s second largest oil 6.00 Today. 6.00 Sunrise. 8.00 Pre-Game 6.00 Cook And The Chef. (R) 6.00 WorldWatch. 10.30 German 6.00 Left Off The Map. 6.30 producer? 9.00 Today Extra Show. 9.00 Cricket. Second Test. 6.25 Short Cuts To Glory. News. 11.00 Spanish News. 11.30 Everyday Gourmet. 7.00 Ent. Summer. (PG) Australia v India. Day 4. Morning (R) 7.00 News. 10.00 David Turkish News. 12.00 Arabic News Tonight. 7.30 Judge Judy. (PG) 11.30 Morning News. session. 11.00 The Lunch Break. Attenborough’s Tasmania. (R) F24. (France) 12.30 ABC America: 8.00 Bold. (PG) 8.30 Studio 5. What does the Latin 12.00 MOVIE: Miss Pettigrew 11.40 Cricket. Australia v India. 11.00 Gardening Australia. (R) World News Tonight. -

06 4-15 TV Guide.Indd 1 4/15/08 7:49:32 AM

PAGE 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2008 Monday Evening April 21, 2008 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With the Stars Samantha Bachelor-Lond Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY , APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS Big Bang How I Met Two Men Rules CSI: Miami Local Late Show-Letterman Late Late KSNK/NBC Deal or No Deal Medium Local Tonight Show Late FOX Bones House Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Intervention I Survived Crime 360 Intervention AMC Ferris Bueller Teen Wolf StirCrazy ANIM Petfinder Animal Cops Houston Animal Precinct Petfinder Animal Cops Houston CNN CNN Election Center Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Dirty Jobs Dirty Jobs Verminators How-Made How-Made Dirty Jobs DISN Finding Nemo So Raven Life With The Suite Montana Replace Kim E! Keep Up Keep Up True Hollywood Story Girls Girls E! News Chelsea Daily 10 Girls ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Fastbreak Baseball Norton TV ESPN2 Arena Football Football E:60 NASCAR Now FAM Greek America's Prom Queen Funniest Home Videos The 700 Club America's Prom Queen FX American History X '70s Show The Riches One Hour Photo HGTV To Sell Curb Potential Potential House House Buy Me Sleep To Sell Curb HIST Modern Marvels Underworld Ancient Discoveries Decoding the Past Modern Marvels LIFE Reba Reba Black and Blue Will Will The Big Match MTV True Life The Paper The Hills The Hills The Paper The Hills The Paper The Real World NICK SpongeBob Drake Home Imp. -

Thursday Morning, March 10

THURSDAY MORNING, MARCH 10 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM 4:30 KATU News This Morning (N) Good Morning America (N) (cc) AM Northwest Who Wants to Be The View Actress Michelle Rodri- Live With Regis and Kelly Talent 2/KATU 2 2 (cc) (Cont’d) (cc) a Millionaire guez. (N) (cc) (TV14) judge Jennifer Lopez. (N) (TVPG) KOIN Local 6 Early at 6 (N) (cc) The Early Show (N) (cc) Let’s Make a Deal (N) (cc) (TVPG) The Price Is Right (N) (cc) (TVG) The Young and the Restless (N) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 (TV14) Newschannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Today Aaron Eckhart; Avril Lavigne performs. (N) (cc) The Nate Berkus Show Do-it-your- 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) self projects. (cc) (TVPG) Sit and Be Fit Between the Curious George Cat in the Hat Super Why! (cc) Dinosaur Train Sesame Street Search for the Sid the Science Clifford the Big Martha Speaks WordWorld (TVY) 10/KOPB 10 10 (cc) (TVG) Lions (TVY) (TVY) Knows a Lot (TVY) (TVY) Blue Bar Pigeon. (TVY) Kid (TVY) Red Dog (TVY) (TVY) Good Day Oregon-6 (N) Good Day Oregon (N) Better (cc) (TVPG) The 700 Club (cc) (TVPG) 12/KPTV 12 12 Portland Public Affairs Paid Paid The Magic School Willa’s Wild Life Through the Bible Zola Levitt Pres- Paid Paid Paid 22/KPXG 5 5 Bus (TVY7) ents (TVG) Changing Your John Hagee Rod Parsley (cc) This Is Your Day Kenneth Cope- Unfolding Majesty Life Change Cafe John Bishop TV Changing Your John Hagee Rod Parsley (cc) This Is Your Day 24/KNMT 20 20 World (TVG) Today (cc) (TVG) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) land (TVG) (cc) World (TVG) Today (cc) (TVG) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) George Lopez George Lopez The Young Icons Just Shoot Me My Name Is Earl My Name Is Earl Maury (cc) (TV14) Swift Justice- Swift Justice- The Steve Wilkos Show Abuse of a 32/KRCW 3 3 (cc) (TVPG) (cc) (TVPG) (TVG) (cc) (TVPG) (TV14) (TV14) Nancy Grace Nancy Grace young boy. -

06 3-13-12 TV Guide.Indd

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, March 13, 2012 Monday Evening March 19, 2012 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With Stars Castle Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , MARCH 16 THROUGH THURSDAY , MARCH 22 KBSH/CBS How I Met 2 Broke G Two Men Mike Hawaii Five-0 Local Late Show Letterman Late KSNK/NBC The Voice Smash Local Tonight Show w/Leno Late FOX House Alcatraz Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Intervention Intervention Intervention Intervention AMC Shawshank R. Shawshank R. ANIM North Woods Law Rattlesnake Republic Rattlesnake Republic North Woods Law Rattlesnake Republic CNN Anderson Cooper 360 Piers Morgan Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 E. B. OutFront Piers Morgan Tonight DISC American Chopper American Chopper Sons of Guns American Chopper Sons of Guns DISN Doc McSt. Beverly Hills Shake It Austin ANT Farm Wizards Wizards E! Fashion Police Khloe Khloe True Hollywood Story Chelsea E! News Chelsea Norton TV ESPN College Basketball College Basketball SportsCenter SportsCenter ESPN2 Women's College Basketball Wm. Basketball Women's College Basketball FAM Pretty Little Liars Secret-Teen Pretty Little Liars The 700 Club Prince Prince FX Iron Man Iron Man HGTV Love It or List It House House House Hunters My House First House House HIST Pawn Pawn American Pickers Pawn Pawn American Pickers Pawn Pawn LIFE The Ugly Truth No Reservations The Ugly Truth Listings: MTV Fantasy Fantasy Fantasy Fantasy Fantasy Fantasy Fantasy Fantasy Jersey Shore NICK My Wife My Wife George George '70s Show '70s Show Friends Friends Friends Friends SCI Being Human Being Human Lost Girl Being Human Lost Girl For your SPIKE Ways Die Ways Die Ways Die Ways Die Ways Die Ways Die Ways Die Ways Die Ways Die Ways Die TBS Fam. -

Corus Entertainment's Powerful Specialty Portfolio Announces Lineup of 2019-2020 Orders

CORUS ENTERTAINMENT’S POWERFUL SPECIALTY PORTFOLIO ANNOUNCES LINEUP OF 2019-2020 ORDERS Corus Specialty Networks Dominate, Claiming Five of the Top 10 Specialty Stations and the Top 5 Kids Channels W Network and Showcase Deliver Heavy-Hitting Dramas and Thrillers: Batwoman, Pearson, Nancy Drew, Katy Keene, Pennyworth, Party of Five and Swamp Thing Returning Seasons of Standout Scripted Hits Include: Supergirl, Charmed, Outlander, The Good Fight, The Sinner, Legacies and More Lifestyle Slate Boasts the Best in Unscripted Series: A Very Brady Renovation, Extreme Makeover: Home Edition, Christina on the Coast, Cupcake Championship and Holiday Wars Corus’ Leading Suite of Children’s Networks Introduce a Spin-Off of The Loud House: Los Casagrandes, New Series Yabba Dabba Dinosaurs, the Milestone 50th Season of Sesame Street and More For additional photography and press kit material visit: http://www.corusent.com To share this release socially visit: http://bit.ly/2K8GHDq For Immediate Release TORONTO, May 30, 2018 – Corus Entertainment announced today its vast lineup of gripping new titles and returning smash-hits for the 2019-2020 broadcast season. The indisputable frontrunner in Canada’s specialty landscape, Corus owns five of the Top 10 channels* including W Network, Showcase, HISTORY®, HGTV Canada and YTV – more than any other broadcaster. Since its launch earlier this spring, Adult Swim ranks in the Top 10 among male millennials****. Claiming the Top 5 kids channels*****, the company continues to be the prominent leader across its impressive suite of children’s networks as well. This announcement follows Corus’ unveiling of 40 new and returning Canadian original series earlier this morning. -

P32 Layout 1

WEDNESDAY, MAY 24, 2017 TV PROGRAMS 04:15 Lip Sync Battle 01:15 Sabrina Secrets Of A Teenage 23:20 Henry Hugglemonster 14:05 Second Wives Club 04:40 Ridiculousness Witch 23:35 The Hive 15:00 E! News 05:05 Disaster Date 01:40 Hank Zipzer 23:45 Loopdidoo 15:15 E! News: Daily Pop 05:30 Sweat Inc. 02:05 Binny And The Ghost 16:10 Keeping Up With The Kardashians 06:20 Life Or Debt 02:30 Binny And The Ghost 17:05 Live From The Red Carpet 00:15 Survivor 07:10 Disorderly Conduct: Video On 02:55 Hank Zipzer 19:00 E! News 02:00 Sharknado 2: The Second One Patrol 03:15 The Hive 20:00 Fashion Police 03:30 Fast & Furious 7 08:05 Disaster Date 03:20 Sabrina Secrets Of A Teenage 21:00 Botched 06:00 Mission: Impossible - Rogue 08:30 Disaster Date Witch 22:00 Botched Nation 08:55 Ridiculousness 03:45 Sabrina Secrets Of A Teenage 23:00 E! News 08:15 Bad Company 09:20 Workaholics Witch 00:20 Street Outlaws 23:15 Hollywood Medium With Tyler 10:15 Licence To Kill 09:45 Disaster Date 04:10 Hank Zipzer 01:10 Todd Sampson's Body Hack Henry 12:30 Fast & Furious 7 10:10 Ridiculousness 04:35 Binny And The Ghost 02:00 Marooned With Ed Stafford 15:00 Mission: Impossible - Rogue 10:35 Impractical Jokers 05:00 Binny And The Ghost 02:50 Still Alive Nation 11:00 Hungry Investors 05:25 Hank Zipzer 03:40 Diesel Brothers 17:15 Run All Night 11:50 The Jim Gaffigan Show 05:45 The Hive 04:30 Storage Hunters UK 19:15 Golden Eye 12:15 Lip Sync Battle 05:50 The 7D 05:00 How Do They Do It? 21:30 San Andreas 12:40 Impractical Jokers 06:00 Jessie 05:30 How Do They Do It? 00:00 Diners, -

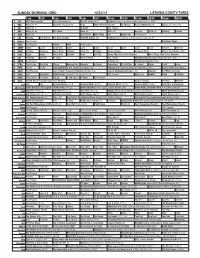

Sunday Morning Grid 12/21/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/21/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Kansas City Chiefs at Pittsburgh Steelers. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Young Men Big Dreams On Money Access Hollywood (N) Skiing U.S. Grand Prix. 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Vista L.A. Outback Explore 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Atlanta Falcons at New Orleans Saints. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Christmas Angel 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Alsace-Hubert Heirloom Meals Man in the Kitchen (TVG) 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Christmas Twister (2012) Casper Van Dien. (PG) 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) República Deportiva (TVG) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia 101 Dalmatians ›› (1996) Glenn Close. -

Special Interest Zenders

TV Uitzendschema - Special Interest zenders Periode 22-8-2016 t/m 18-9-2016 Doelgroep 25-59 jaar Dag Datum Tijd Spotlengte Zender Progn. grp's P Programma voor Programma na ma 22-08-16 08:10 20+5 E! 0,0 e! entertainment e! entertainment ma 22-08-16 08:50 20+5 Xite 0,0 after school after school ma 22-08-16 09:20 20+5 Xite 0,0 after school after school ma 22-08-16 09:40 20+5 Xite 0,0 after school after school ma 22-08-16 10:14 20+5 TLC 0,3 my 600lb life my 600lb life ma 22-08-16 11:20 20+5 Xite 0,0 after school after school ma 22-08-16 11:30 20+5 SlamTV 0,0 most wanted most wanted ma 22-08-16 11:47 20+5 TLC 0,1 gypsy sisters gypsy sisters ma 22-08-16 11:55 20+5 E! 0,0 e! entertainment e! entertainment ma 22-08-16 12:25 5+20 History 0,0 storage wars storage wars ma 22-08-16 12:31 20+5 RTL Lounge 0,0 wonderland wonderland ma 22-08-16 12:55 20+5 Crime Inv 0,0 crimes that shook britain 2 crimes that shook britain 2 ma 22-08-16 13:00 20+5 SlamTV 0,0 slam!non-stop slam!non-stop ma 22-08-16 13:01 20+5 Comedy 0,0 bobs burgers bobs burgers ma 22-08-16 13:08 20+5 Crime Inv 0,0 fatal vows fatal vows ma 22-08-16 13:12 20+5 MTV 0,0 made made ma 22-08-16 13:23 20+5 Comedy 0,0 american dad american dad ma 22-08-16 13:56 20+5 Crime Inv 0,0 fatal vows fatal vows ma 22-08-16 14:50 20+5 Xite 0,0 standaard standaard ma 22-08-16 15:37 20+5 E! 0,0 e! entertainment e! entertainment ma 22-08-16 15:50 20+5 Xite 0,0 standaard standaard ma 22-08-16 16:44 20+5 History 0,1 pawn stars uk 0:5hr pawn stars uk 0:5hr ma 22-08-16 17:09 20+5 E! 0,0 e! entertainment e! entertainment -

Stargazers, Ax-Men and Milkmaids the Men Who Surveyed Mason and Dixon’S Line

Stargazers, Ax-men and Milkmaids The Men who Surveyed Mason and Dixon’s Line Todd M. BABCOCK, USA Key words: Mason, Charles; Dixon, Jeremiah; Surveyors; Penn; Calvert; Pre-revolutionary history. ABSTRACT In 1763, Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon were called upon by the colonial proprietors of Pennsylvania and Maryland to demark the long disputed boundary that eventually came to bear their name. During the ensuing four years, Mason and Dixon cleared a line (visto) eight or nine yards wide through the virgin forests of the western frontier, crossed the Allegheny Mountains, and set 500 pound monuments every mile along the way. While it is true that Mason and Dixon accomplished the task of establishing and marking the complex boundary between the Penn’s and Calvert’s, it can hardly be said that they did it alone. This tremendous undertaking required the skills and labor of a large work party. During the late summer of 1767, as many as 115 men were employed as ax-men, instrument bearers, cooks, tent keepers, shepherds and even a milkmaid. The journal of the survey that was kept by Charles Mason contains a wealth of information pertaining to the measurements and astronomical observations taken during the course of the survey. Little is mentioned in his journal about the men who were employed for the work or of the tremendous undertaking necessary to clear the lines for the surveyors to perform their observations. Moses McLean, a colonial surveyor, was hired as the Steward of the survey and was charged with the management of the work force necessary to accomplish this tremendous undertaking. -

Drug Bust Linked to Fatal Shooting State Will Have to Wait

1A SUNDAY, MAY 12, 2013 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | $1.00 Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM For one sports mom, Summer job SUNDAY EDITION Mother’s Day means a search begins day without football. 1D for local teens. 1C Drug bust linked to fatal shooting Homeowner killed Department. bers of the Multi- but does not say whether Johns Lonnie Ray “Trey” Johns III, J u r i s d i c t i o n a l was taken into custody before or Alleged after allegedly firing 19, faces charges of possession of Task Force after the shooting. at narcotics squad. more than 20 grams of marijuana ordered him to According to the report, “infor- and drug paraphernalia. drop the weapon mation was received in reference gunman He was arrested at 611 NW but he fired at to an indoor grow operation at By DEREK GILLIAM Bronco Terrace, during the same them instead. (the property).” [email protected] narcotics operation that resulted The officers Johns During the arrest, police took was big in the death of the homeowner, returned fire, from Johns of three “plant pots,” A Lake City man was arrested Alberto F. Valdes, 58. killing Valdes. listed on the report as drug para- in a narcotics operation that left According to sheriff’s report, The arrest report says that “dur- phernalia; an AR-15 assault rifle tipper another man dead late Wednesday, Valdes exited the home brandish- ing the incident a resident of 611 equipped with “tactical light and according to a report released ing a shotgun at about 11:50 p.m.