Sovereignty, Place and Possibility Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

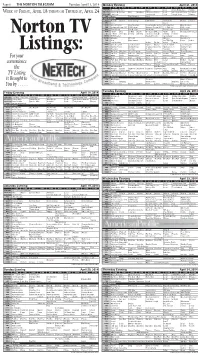

06 4-15-14 TV Guide.Indd

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2014 Monday Evening April 21, 2014 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With Stars Castle Local Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline WEEK OF FRIDAY, APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY, APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS 2 Broke G Friends Mike Big Bang NCIS: Los Angeles Local Late Show Letterman Ferguson KSNK/NBC The Voice The Blacklist Local Tonight Show Meyers FOX Bones The Following Local Cable Channels A&E Duck D. Duck D. Duck Dynasty Bates Motel Bates Motel Duck D. Duck D. AMC Jaws Jaws 2 ANIM River Monsters River Monsters Rocky Bounty Hunters River Monsters River Monsters CNN Anderson Cooper 360 CNN Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 E. B. OutFront CNN Tonight DISC Fast N' Loud Fast N' Loud Car Hoards Fast N' Loud Car Hoards DISN I Didn't Dog Liv-Mad. Austin Good Luck Win, Lose Austin Dog Good Luck Good Luck E! E! News The Fabul Chrisley Chrisley Secret Societies Of Chelsea E! News Norton TV ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Olbermann ESPN2 NFL Live 30 for 30 NFL Live SportsCenter FAM Hop Who Framed The 700 Club Prince Prince FX Step Brothers Archer Archer Archer Tomcats HGTV Love It or List It Love It or List It Hunters Hunters Love It or List It Love It or List It HIST Swamp People Swamp People Down East Dickering America's Book Swamp People LIFE Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Listings: MTV Girl Code Girl Code 16 and Pregnant 16 and Pregnant House of Food 16 and Pregnant NICK Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Friends Friends Friends SCI Metal Metal Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Metal Metal For your SPIKE Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Jail Jail TBS Fam. -

06 10-26-10 TV Guide.Indd 1 10/26/10 8:08:17 AM

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, October 26, 2010 Monday Evening November 1, 2010 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With Stars Castle Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , OCT . 29 THROUGH THURSDAY , NOV . 4 KBSH/CBS How I Met Rules Two Men Mike Hawaii Five-0 Local Late Show Letterman Late KSNK/NBC Chuck The Women of SNL Local Tonight Show w/Leno Late FOX MLB Baseball Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Hoarders Hoarders Intervention Intervention AMC Red Planet Rubicon Mad Men Volcano ANIM Pit Bulls-Parole Pit Bulls-Parole River Monsters Pit Bulls-Parole Pit Bulls-Parole CNN Parker Spitzer Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Wreck Wreck American Chopper American Chopper Wreck Wreck American Chopper DISN Den Brother Deck Hannah Hannah Deck Deck Hannah Hannah E! Kardashian True Hollywood Story Fashion Soup Pres Chelsea E! News Chelsea Norton TV ESPN Countdown NFL Football SportsCenter ESPN2 2010 Poker 2010 Poker 2010 Poker E:60 SportsNation FAM Funniest Home Videos Funniest Home Videos Funniest Home Videos The 700 Club My Wife My Wife FX Spider-Man 3 Two Men Two Men Malcolm HGTV Property First House Designed House Hunters My First My First House Designed HIST Pawn Pawn American American Pawn Pawn Ancient Aliens Pawn Pawn LIFE Reba Reba Lying to Be Perfect How I Met How I Met The Fairy Jobmother Listings: MTV Jersey Shore World World World Buried World Buried Jersey Shore NICK My Wife My Wife Chris Chris Lopez Lopez The Nanny The Nanny The Nanny The Nanny SCI Scare Scare Scare Scare Scare Scare Gundam Gundam Darkness Darkness For your SPIKE Star Wars-Phantom Star Wars-Phantom Disorderly Con. -

On Reality Television During the Great Recession

Societies 2012, 2, 235–251; doi:10.3390/soc2040235 OPEN ACCESS societies ISSN 2075-4698 www.mdpi.com/journal/societies Article Working Stiff(s) on Reality Television during the Great Recession Sean Brayton Department of Kinesiology and Physical Education, University of Lethbridge, 4401 University Drive, Lethbridge, AB, T1K 3M4, Canada; E-Mail: [email protected] Received: 6 August 2012; in revised form: 22 October 2012 / Accepted: 23 October 2012 / Published: 29 October 2012 Abstract: This essay traces some of the narratives and cultural politics of work on reality television after the economic crash of 2008. Specifically, it discusses the emergence of paid labor shows like Ax Men, Black Gold and Coal and a resurgent interest in working bodies at a time when the working class in the US seems all but consigned to the dustbin of history. As an implicit response to the crisis of masculinity during the Great Recession these programs present an imagined revival of manliness through the valorization of muscle work, which can be read in dialectical ways that pivot around the white male body in peril. In Ax Men, Black Gold and Coal, we find not only the return of labor but, moreover, the re-embodiment of value as loggers, roughnecks and miners risk both life and limb to reach company quotas. Paid labor shows, in other words, present a complicated popular pedagogy of late capitalism and the body, one that relies on anachronistic narratives of white masculinity in the workplace to provide an acute critique of expendability of the body and the hardships of physical labor. -

Today's Television

54 TV TUESDAY DECEMBER 29 2020 Start the day Zits Insanity Streak lHAD~UCflA UNFORTUNATE::!.'(, t;HE: with a laugh TIMr;;:AT!-UN OL-DME'1VUR ... OW NoTM1NG MUCM, How are dogs like cell JUST $OCllL 1>1STlNC1NG ,.. phones? 1>.NI> YoO? They both have collar id. wHaT kind of key can never unlock a door? A monkey. Snake Tales Swamp I OON'"r -.HIN< -rHl:S Today’s quiz IS GOING "l"O SE. .. 1. is a monteith a type of bowl, cape or curtain? 291220 2. The tangelo is a hybrid of which two fruits? f fq()J/ 3. What is a farthingale? T oday’S TeleViSion 4. Which country is the nine SeVen abc SbS Ten world’s second largest oil 6.00 Today. 6.00 Sunrise. 8.00 Pre-Game 6.00 Cook And The Chef. (R) 6.00 WorldWatch. 10.30 German 6.00 Left Off The Map. 6.30 producer? 9.00 Today Extra Show. 9.00 Cricket. Second Test. 6.25 Short Cuts To Glory. News. 11.00 Spanish News. 11.30 Everyday Gourmet. 7.00 Ent. Summer. (PG) Australia v India. Day 4. Morning (R) 7.00 News. 10.00 David Turkish News. 12.00 Arabic News Tonight. 7.30 Judge Judy. (PG) 11.30 Morning News. session. 11.00 The Lunch Break. Attenborough’s Tasmania. (R) F24. (France) 12.30 ABC America: 8.00 Bold. (PG) 8.30 Studio 5. What does the Latin 12.00 MOVIE: Miss Pettigrew 11.40 Cricket. Australia v India. 11.00 Gardening Australia. (R) World News Tonight. -

And You Will Be My Witnesses in Jerusalem, in All Judea and Samaria, and to the Ends of the Earth.” Acts 1:8 New Revised Standard Version (NRSV)

8 But you will receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you; and you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem, in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth.” Acts 1:8 New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) Christian Church in Ohio DISCIPLES OF CHRIST A covenant network of congregations in mission: We are the Body of Christ gifted and called in covenant together as Disciples of Christ to be centers of transformation on the new mission frontier of our own communities *This page intentionally left blank Christian Church in Ohio D I S C I P L E S O F C H R I S T Values and Seeds of Vision A covenant network of congregations in mission: We are the body of Christ gifted and called in covenant together as Disciples of Christ to be centers of transformation on the new mission frontier of our communities. Strengthening Relationships and Building Networks Leadership Development Congregational Transformation and Evangelism In covenant together, we are gifted and called to become a true community, by Building trust through open clear communication. Listening to one another’s hopes and dreams. Caring for one another in times of joy and pain. Sharing our transformation experiences of Jesus Christ with our communities around us. Maintaining the highest level of ethical integrity. Helping to network our congregations’ effective ministries with one another. Offering up assistance in discerning the gifts, calling, and unique missional opportunities of each other, and facilitate leader development and educational opportunities. Finding ways to empower gifts of individuals, established clergy and laity as mission team leaders, and equipping them with the resources to do ministry. -

Thursday Morning, March 10

THURSDAY MORNING, MARCH 10 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM 4:30 KATU News This Morning (N) Good Morning America (N) (cc) AM Northwest Who Wants to Be The View Actress Michelle Rodri- Live With Regis and Kelly Talent 2/KATU 2 2 (cc) (Cont’d) (cc) a Millionaire guez. (N) (cc) (TV14) judge Jennifer Lopez. (N) (TVPG) KOIN Local 6 Early at 6 (N) (cc) The Early Show (N) (cc) Let’s Make a Deal (N) (cc) (TVPG) The Price Is Right (N) (cc) (TVG) The Young and the Restless (N) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 (TV14) Newschannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Today Aaron Eckhart; Avril Lavigne performs. (N) (cc) The Nate Berkus Show Do-it-your- 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) self projects. (cc) (TVPG) Sit and Be Fit Between the Curious George Cat in the Hat Super Why! (cc) Dinosaur Train Sesame Street Search for the Sid the Science Clifford the Big Martha Speaks WordWorld (TVY) 10/KOPB 10 10 (cc) (TVG) Lions (TVY) (TVY) Knows a Lot (TVY) (TVY) Blue Bar Pigeon. (TVY) Kid (TVY) Red Dog (TVY) (TVY) Good Day Oregon-6 (N) Good Day Oregon (N) Better (cc) (TVPG) The 700 Club (cc) (TVPG) 12/KPTV 12 12 Portland Public Affairs Paid Paid The Magic School Willa’s Wild Life Through the Bible Zola Levitt Pres- Paid Paid Paid 22/KPXG 5 5 Bus (TVY7) ents (TVG) Changing Your John Hagee Rod Parsley (cc) This Is Your Day Kenneth Cope- Unfolding Majesty Life Change Cafe John Bishop TV Changing Your John Hagee Rod Parsley (cc) This Is Your Day 24/KNMT 20 20 World (TVG) Today (cc) (TVG) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) land (TVG) (cc) World (TVG) Today (cc) (TVG) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) George Lopez George Lopez The Young Icons Just Shoot Me My Name Is Earl My Name Is Earl Maury (cc) (TV14) Swift Justice- Swift Justice- The Steve Wilkos Show Abuse of a 32/KRCW 3 3 (cc) (TVPG) (cc) (TVPG) (TVG) (cc) (TVPG) (TV14) (TV14) Nancy Grace Nancy Grace young boy. -

1 NUMBER 96 FALL 2019-FALL 2020 in Memoriam

Virginia Woolf Miscellany NUMBER 96 FALL 2019-FALL 2020 Centennial Contemplations on Early Work (16) while Rosie Reynolds examines the numerous by Virginia Woolf and Leonard Woolf o o o o references to aunts in The Voyage Out and examines You can access issues of the the narrative function of Rachel’s aunt, Helen To observe the centennial of Virginia Woolf’s Virginia Woolf Miscellany Ambrose, exploring Helen’s perspective as well as early works, The Voyage Out, and Night and online on WordPress at the identity and self-revelation associated with the Day, and also Leonard Woolf’s The Village in the https://virginiawoolfmiscellany. emerging relationship between Rachel and fellow Jungle. I invited readers to adopt Nobel Laureate wordpress.com/ tourist Terence. Daniel Kahneman’s approach to problem-solving and decision making. In Thinking Fast and Slow, Virginia Woolf Miscellany: In her essay, Mine Özyurt Kılıç responds directly Kahneman distinguishes between fast thinking— Editorial Board and the Editors to the call with a “slow” reading of the production typically intuitive, impressionistic and reliant on See page 2 process that characterizes the work of Hogarth Press, associative memory—and the more deliberate, Editorial Policies particularly in contrast to the mechanized systems precise, detailed, and logical process he calls slow See page 6 from which it was distinguished. She draws upon “A thinking. Fast thinking is intuitive, impressionistic, y Mark on the Wall,” “Kew Gardens,” and “Modern and dependent upon associative memory. Slow – TABLE OF CONTENTS – Fiction,” to develop the notion and explore the thinking is deliberate, precise, detailed, and logical. -

06 3-13-12 TV Guide.Indd

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, March 13, 2012 Monday Evening March 19, 2012 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With Stars Castle Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , MARCH 16 THROUGH THURSDAY , MARCH 22 KBSH/CBS How I Met 2 Broke G Two Men Mike Hawaii Five-0 Local Late Show Letterman Late KSNK/NBC The Voice Smash Local Tonight Show w/Leno Late FOX House Alcatraz Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Intervention Intervention Intervention Intervention AMC Shawshank R. Shawshank R. ANIM North Woods Law Rattlesnake Republic Rattlesnake Republic North Woods Law Rattlesnake Republic CNN Anderson Cooper 360 Piers Morgan Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 E. B. OutFront Piers Morgan Tonight DISC American Chopper American Chopper Sons of Guns American Chopper Sons of Guns DISN Doc McSt. Beverly Hills Shake It Austin ANT Farm Wizards Wizards E! Fashion Police Khloe Khloe True Hollywood Story Chelsea E! News Chelsea Norton TV ESPN College Basketball College Basketball SportsCenter SportsCenter ESPN2 Women's College Basketball Wm. Basketball Women's College Basketball FAM Pretty Little Liars Secret-Teen Pretty Little Liars The 700 Club Prince Prince FX Iron Man Iron Man HGTV Love It or List It House House House Hunters My House First House House HIST Pawn Pawn American Pickers Pawn Pawn American Pickers Pawn Pawn LIFE The Ugly Truth No Reservations The Ugly Truth Listings: MTV Fantasy Fantasy Fantasy Fantasy Fantasy Fantasy Fantasy Fantasy Jersey Shore NICK My Wife My Wife George George '70s Show '70s Show Friends Friends Friends Friends SCI Being Human Being Human Lost Girl Being Human Lost Girl For your SPIKE Ways Die Ways Die Ways Die Ways Die Ways Die Ways Die Ways Die Ways Die Ways Die Ways Die TBS Fam. -

P32 Layout 1

WEDNESDAY, MAY 24, 2017 TV PROGRAMS 04:15 Lip Sync Battle 01:15 Sabrina Secrets Of A Teenage 23:20 Henry Hugglemonster 14:05 Second Wives Club 04:40 Ridiculousness Witch 23:35 The Hive 15:00 E! News 05:05 Disaster Date 01:40 Hank Zipzer 23:45 Loopdidoo 15:15 E! News: Daily Pop 05:30 Sweat Inc. 02:05 Binny And The Ghost 16:10 Keeping Up With The Kardashians 06:20 Life Or Debt 02:30 Binny And The Ghost 17:05 Live From The Red Carpet 00:15 Survivor 07:10 Disorderly Conduct: Video On 02:55 Hank Zipzer 19:00 E! News 02:00 Sharknado 2: The Second One Patrol 03:15 The Hive 20:00 Fashion Police 03:30 Fast & Furious 7 08:05 Disaster Date 03:20 Sabrina Secrets Of A Teenage 21:00 Botched 06:00 Mission: Impossible - Rogue 08:30 Disaster Date Witch 22:00 Botched Nation 08:55 Ridiculousness 03:45 Sabrina Secrets Of A Teenage 23:00 E! News 08:15 Bad Company 09:20 Workaholics Witch 00:20 Street Outlaws 23:15 Hollywood Medium With Tyler 10:15 Licence To Kill 09:45 Disaster Date 04:10 Hank Zipzer 01:10 Todd Sampson's Body Hack Henry 12:30 Fast & Furious 7 10:10 Ridiculousness 04:35 Binny And The Ghost 02:00 Marooned With Ed Stafford 15:00 Mission: Impossible - Rogue 10:35 Impractical Jokers 05:00 Binny And The Ghost 02:50 Still Alive Nation 11:00 Hungry Investors 05:25 Hank Zipzer 03:40 Diesel Brothers 17:15 Run All Night 11:50 The Jim Gaffigan Show 05:45 The Hive 04:30 Storage Hunters UK 19:15 Golden Eye 12:15 Lip Sync Battle 05:50 The 7D 05:00 How Do They Do It? 21:30 San Andreas 12:40 Impractical Jokers 06:00 Jessie 05:30 How Do They Do It? 00:00 Diners, -

Drug Bust Linked to Fatal Shooting State Will Have to Wait

1A SUNDAY, MAY 12, 2013 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | $1.00 Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM For one sports mom, Summer job SUNDAY EDITION Mother’s Day means a search begins day without football. 1D for local teens. 1C Drug bust linked to fatal shooting Homeowner killed Department. bers of the Multi- but does not say whether Johns Lonnie Ray “Trey” Johns III, J u r i s d i c t i o n a l was taken into custody before or Alleged after allegedly firing 19, faces charges of possession of Task Force after the shooting. at narcotics squad. more than 20 grams of marijuana ordered him to According to the report, “infor- and drug paraphernalia. drop the weapon mation was received in reference gunman He was arrested at 611 NW but he fired at to an indoor grow operation at By DEREK GILLIAM Bronco Terrace, during the same them instead. (the property).” [email protected] narcotics operation that resulted The officers Johns During the arrest, police took was big in the death of the homeowner, returned fire, from Johns of three “plant pots,” A Lake City man was arrested Alberto F. Valdes, 58. killing Valdes. listed on the report as drug para- in a narcotics operation that left According to sheriff’s report, The arrest report says that “dur- phernalia; an AR-15 assault rifle tipper another man dead late Wednesday, Valdes exited the home brandish- ing the incident a resident of 611 equipped with “tactical light and according to a report released ing a shotgun at about 11:50 p.m. -

Outdoor Channel Asia Enters 2018 with Exclusive Original Productions and Asia Content Investment

OUTDOOR CHANNEL ASIA ENTERS 2018 WITH EXCLUSIVE ORIGINAL PRODUCTIONS AND ASIA CONTENT INVESTMENT Outdoor Channel tightly focused on best programming themed around adventure, challenge and survival SINGAPORE (January 11, 2018) – Outdoor Channel Asia hails the new year with a stellar line-up of programming themed around adventure, challenge and survival. Headlining in 2018 are three spectacular exclusive original productions: Survival Science, Wild Ops, and The Seahunter. In Survival Science, human limits are put to the test under extreme outdoor circumstances; find out what it takes for rangers to save wild animals in Wild Ops and enjoy authentic fishing adventures with personality Captain Rob Fordyce on The Seahunter. Popular returning series include Dropped, Hollywood Weapons, Wardens and Trev Gowdy’s Monster Fish. Outdoor Channel makes a major investment in Asian outdoor lifestyle content Lost At Sea and Off The Hook from leading production house GO ASEAN as well as adventure and challenge series Miss Adventures, Breaking 60, Challenge Accepted and Bushwhacked. In conjunction with International Women Day, Miss Adventures will premiere on 8 March 2018 and celebrate the achievements of women globally. Breaking 60 will see individuals attempt to run all four of Hong Kong’s ultra trails totalling 298km, non stop and unsupported in less than 60 hours. As part of Outdoor Channel’s partnership with A+E, selected premium A+E titles like Swamp People, Mountain Men, Alaska’s Off Road Warriors, Ax Men, Billy The Exterminator, Duck Dynasty and Ride N Seek will also debut on the channel in 2018 reinforcing Outdoor Channel as the ultimate destination for adventure, survival and outdoor lifestyle programming. -

In the End Is the Beginning: an Inquiry Into the Meaning of the Religion Clauses Jonathan Van Patten, University of South Dakota School of Law

University of South Dakota School of Law From the SelectedWorks of Jonathan Van Patten 1983 In the End is the Beginning: An Inquiry into the Meaning of the Religion Clauses Jonathan Van Patten, University of South Dakota School of Law Available at: https://works.bepress.com/jonathan_vanpatten/11/ ARTICLES IN THE END IS THE BEGINNING: AN INQUIRY INTO THE MEANING OF THE RELIGION CLAUSES JONATHAN K. VAN PATTEN* I. INTRODUCTION We have in America a tradition of religious liberty. This tradition antedates the Constitution and is exemplified in such documents as the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom, enacted in 1785: [N]o man shall be compelled to frequent or support any religious worship, place or ministry whatsoever, nor shall be enforced, re- strained, molested, or burthened, in his body or goods, nor shall otherwise suffer on account of his religious opinions or belief; but that all men shall be free to profess, and by argument to maintain, their opinions in matters of religion, and that the same shall in no wise diminish, enlarge, or affect their civil capacities.' Religious liberty, whether expressed as freedom of the individual con- science or freedom of a group to worship or to practice its religious beliefs, has generally been a "preferred" liberty. This liberty has not been without its problems. That is, religious liberty itself has been a source of tension in American society. To use a New Testament image, the demands of Caesar conflict, at times, with the demands of God.2 Governmental regulation of the health, safety, welfare, and morals of its citizens will provoke, from time to time, the claim by some citizens for an exemption from such regulation on account of reli- gious beliefs.