Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canberra Light Rail – Commonwealth Park to Woden

CANBERRA LIGHT RAIL – COMMONWEALTH PARK TO WODEN Preliminary Environmental Assessment 18310 Canberra Light Rail – Commonwealth Park to Woden 1.0 2 July 2019 www.rpsgroup.com PRELIMINARY ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT Document Status Version Review Purpose of document Authored by Reviewed by Approved by date 1 Final Belinda Bock Angus King Gareth Thomas 2 July 2019 2 3 Approval for issue Gareth Thomas 2 July 2019 pp This report was prepared by RPS Manidis Roberts Pty Ltd (‘RPS’) within the terms of its engagement and in direct response to a scope of services. This report is strictly limited to the purpose and the facts and matters stated in it and does not apply directly or indirectly and must not be used for any other application, purpose, use or matter. In preparing the report, RPS may have relied upon information provided to it at the time by other parties. RPS accepts no responsibility as to the accuracy or completeness of information provided by those parties at the time of preparing the report. The report does not take into account any changes in information that may have occurred since the publication of the report. If the information relied upon is subsequently determined to be false, inaccurate or incomplete then it is possible that the observations and conclusions expressed in the report may have changed. RPS does not warrant the contents of this report and shall not assume any responsibility or liability for loss whatsoever to any third party caused by, related to or arising out of any use or reliance on the report howsoever. -

WVCC Submission Draft Woden Town Centre Master Plan

Submission Draft Master Plan for Woden Town Centre (2015) PO Box 280 Woden ACT 2606; e-mail: [email protected] www.wvcc.org.au Facebook: /WodenValleyCommunityCouncil Twitter: WVCC_Inc WVCC submission on the Draft Master Plan for Woden Town Centre (2015) The Woden Valley Community Council (WVCC) is a non-political, voluntary lobby group for the Woden Valley community. We focus on a wide range of issues such as planning, community facilities and infrastructure, parks and open space, public transport, parking, education, the environment and health. Community Councils are officially recognised by the ACT Government and are consulted by government on issues affecting our communities. History The WVCC was formed in 2001 as work begun on the Woden Town Master Plan which was subsequently released in 2004. The WVCC invested a significant amount of work into the development of the 2004 Master Plan, however it was not incorporated into the Territory plan and had ‘No statutory status’. After some ad hoc development proposals at various sites around the Woden town centre over the years that were not compliant with the 2004 Master Plan, we welcomed the announcement that a new master plan planning process would start. Consultation with the WVCC started in late 2012 with the Environment and Planning Directorate (EPD) presenting at several WVCC public meetings on this issue. WVCC appreciates the extensive community consultation that preceded the Draft Plan, the results of which have been helpfully consolidated and recorded in the Community Engagement Report Stage1) of October 2014. One issue of concern to the WVCC is that a community stakeholder workshop, similar to the meeting held with lessees and traders, was not conducted. -

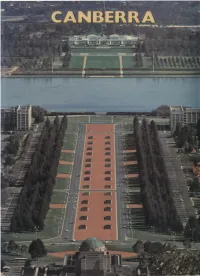

C T E D G S L R C B a B W S C I a D

Canberra is recognised as one of the world’s most successful examples of planned city development. In sixty years it has grown from a collection of surveyors’ tents to Australia’s largest inland city. Because it has developed so rapidly most of Canberra’s 200,000 citizens were born elsewhere. This book attempts to capture some aspects of life in Canberra — the buildings, the seasons, people at work and play, the countryside — so that residents of the national capital can give an impression of its moods and lifestyle to relatives and friends far away. Designed by ANU Graphic Design/ Stephen Cole Canberra is recognised as one of the world’s most successful examples of planned city development. In sixty years it has grown from a collection of surveyors’ tents to Australia’s largest inland city. Because it has developed so rapidly most of Canberra’s 200,000 citizens were born elsewhere. This book attempts to capture some aspects of life in Canberra — the buildings, the seasons, people at work and play, the countryside — so that residents of the national capital can give an impression of its moods and lifestyle to relatives and friends far away. Designed by ANU Graphic Design/ Stephen Cole This book was published by ANU Press between 1965–1991. This republication is part of the digitisation project being carried out by Scholarly Information Services/Library and ANU Press. This project aims to make past scholarly works published by The Australian National University available to a global audience under its open-access policy. First published in Australia 1978 Printed in Singapore for the Australian National University Press, Canberra by Toppan Printing Co., Singapore ® The Australian National University 1978 This book is copyright. -

High Society Brochure(2).Pdf

HIGH SOCIETYHIGH CANBERRA’S TALLEST TOWERS 37m 60m 70m 75m 82m 88m 93m 93m 96m 100m 113m –––– –––– –––– –––– –––– –––– –––– –––– –––– –––– – –––– CBD BUILDINGS SENTINEL INFINITY SKY PLAZA GRAND CENTRAL WAYFARER LOVETT TOWER STATUE OF BIG BEN HIGH SOCIETY CANBERRA CANBERRA CANBERRA CANBERRA CANBERRA CANBERRA CANBERRA LIBERTY LONDON CANBERRA Geocon Geocon Geocon Canberra’s previous NEW YORK Canberra’s new highest Zapari highest building building by Geocon 5 HIGH SOCIETYHIGH ELEVATE EXPECTATIONS Standing unchallenged as the tallest residential tower in Canberra, High Society marks the glittering jewel in the Republic crown. It is, quite simply, the peak of luxury living. 7 Spectre Silverfin Sollace Wellness Centre Sollace Wellness Centre SKY PARK POOL SAUNA YOGA SPACE WELCOME TO CANBERRA’S MOST AMENITY Sollace Wellness Centre Martini Room 1962 Thunderball GYM DINING & KITCHEN WINE CELLAR KIDS SPACE ABUNDANT LIVING Life should be lived and lived well. To deliver the finest in contemporary lifestyles, High Society surrounds you with uncompromising levels of private and public amenity, spanning everything from state-of-the-art recreation facilities to inspired entertainment and social settings. Royale Vanquish Ryder Mi6 CINEMA CAR WASH BIKE HUB WORKSPACE HMSS A View to Kill CONCIERGE OBSERVATION DECK AMENITY RICH Spectre SKY PARK Relax in the clouds. Marvel at the sunset. Revel under the stars. The spectacular rooftop Sky Park is available for the private use of residents and their guests with barbecues, sun lounges and a choice of open and covered spaces. HIGH SOCIETYHIGH Silverfin POOL High Society’s heated outdoor pool allows you to swim and train all year round. The pool area is surrounded by cabanas, day beds and lounges in a beautifully-landscaped setting. -

Approved Major Development Plan

APPROVED MAJOR DEVELOPMENT PLAN 6 BRINDABELLA CIRCUIT OFFICE DEVELOPMENT July 2019 Table of Contents Glossary.......................................................................................................................................3 Chapter One: Introduction ........................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Location ........................................................................................................................................5 1.2 The proposal.................................................................................................................................6 1.3 The project....................................................................................................................................6 1.4 Proponent details.........................................................................................................................7 1.5 Objective.......................................................................................................................................8 1.6 Major development plan process................................................................................................8 1.7 National Construction Code.........................................................................................................9 1.8 NCP Employment Location...........................................................................................................9 1.9 Construction Environmental Management -

Mr Andrew Barr MLA Chief Minister GPO Box 1020 CANBERRA ACT 2601

Mr Andrew Barr MLA Chief Minister GPO Box 1020 CANBERRA ACT 2601 Dear Chief Minister Request for the ACT Government to purchase Borrowdale House and Bank House in Woden We are writing about the impact the proposed W2 development will have on Woden’s focal point and civic area (the east west connection from the transport interchange, through the Town Square to the Library) and the diminishing ability to deliver the vision in the Master Plan for the Town Square to be the centre for social and community activity in the Town Centre. With significant population growth in and around the Town Centre, Woden is doing its share of urban infill with 25 residential towers and around 10,000 people earmarked for the Centre to date. To maintain our quality of life and encourage downsizing to the Centre (freeing up housing stock), we request that a land use plan is developed to balance homes, jobs, public spaces and community facilities to ensure that the Town Centre becomes an attractive urban hub servicing the needs of much of the population in Canberra’s south. For the Town Square to be the focal point for social and community activity it needs to be sunny and have anchor buildings such as the CIT and an arts/cultural/community centre on its perimeter to attract people to it again and again. It needs to be a place that can host events and live music to support business activity without residents complaining. A focal point is supposed to be the ‘beating heart’ of the centre that creates an identity and a sense of belonging for the well-being of residents. -

Guide to the May Mandelbaum Edel Papers, 1928-1996

Guide to the May Mandelbaum Edel papers, 1928-1996 Adam Fielding Funding for the processing of this collection was provided by the Smithsonian Institution's Collections Care and Preservation Fund. 2014 July National Anthropological Archives Museum Support Center 4210 Silver Hill Road Suitland 20746 [email protected] http://www.anthropology.si.edu/naa/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical/Historical note.............................................................................................. 2 Selected Bibliography...................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Research, circa 1930s - circa 1960s........................................................ 5 Series 2: Writings, 1933-1995 (bulk 1933-1965)..................................................... -

Nurses Board of the Aystralian Capital Territory

Australian Capital Territory Gazette Nurses Act 1988 No. 558. 18 April 1994 NURSES BOARD OF THE AYSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY POBol[ 1309 Pb: (06)205 1600 nJGCERANONG ACf 2900 Fu: (06)ZOS 160% NURSES REGISfERED IN THE A.C.T. UNDER THE NURSES ACT 1988 In accordance with section 59 of the Nurses Act 1988 the following is a list of nurses registered under the Act. //~/' John Schaaps Registrar 23 March 1994 Authorised by the ACT Parliamentary Counsel-also accessible at www.legislation.aclgov.au 'ag_ 1 ABIIEY ANNETT! 000000167 pro 13 CLIFF STREET YASS H9W 2582 ABIIEY JULIE 000002147 pro 32 FULLWOOD STREET WE9TON ACT 2611 ADAMS JULIE 000001667 pro WODEN VALLEY HOSPITAL PO BOX 11 WODEN ACT 2606 ADAMS HELINDA 000002428 pro 135 LANODON AVENUE WMHIASSA ACT 2903 ADAMS ROBYN 000003560 pro COHHUHITY NURSING ACTHIiCS CIVIC ACT 2601 ADAMS VICKI 000004111 pro 1 HUHE STRIET OOULIIUR/f NSW 2580 » c: ADAMS IRENE 000005402 po. 11 GRAYSON STREIT HACKETT ACT 2602 5' o :::l. ADAMS PAULINE 000005621 pro 18 CANTERBURY TERRACE VICTORIA PARK EAST WA 6101 CD '"C. ACGETT YVONNE 000001098 pro 24 STEWART CRESCENT HELBA ACT 2615 ~ AGNEW MAXINE 000000746 pro CALVARY H09PITAL HAYDON DRIVE BRUCE ACT 2615 5' CD AHERN JUDlTH 000003341 pro CALVARY H09PITAL HATERNITY SECTION lS/HAYDON DR BRUCE ACT 2617 ~ AHKIN JULIE 000000168 pro IIEOA DISTRICT HOSPITAL HCKEE DRIVE BEOA HSW 2550 "U III :::l. AIDNEY HAUREEN 000004026 pro 55 HEDGERLEY CHI/fNOR OXFORD UK ox9 4TJ iir 3 AIRD DEIIBIE 000003614 pro WODEN VALLEY HOSPITAL PO BOX 11 WODEN ACT 2606 CD ::J OJ A19TROPE HIONON 000002716 pro PO BOX 609 gUEMBEYM HSW 2620 -< AITCHISON JENNIFER 000002429 pro CITY HEALTH CENTRE HOORE AND ALINGS STS CMBERRA ACT 2601 o c: ::J AITKIN BEVERLY 000001341 pro 26 1I0RROWDALE STREET RED HILL ACT 2603 '"CD J; ALBRECHT LEMNE 000001668 pro 4 HYNES PLACE CHISHOLH ACT 2905 en ACT o ALDCRO . -

Trek Cycles Unit 3/46 Botany Street Phillip ACT

Sales / Leasing Investment Portfolio Auctions Management Trek Cycles Unit 3/46 Botany Street Phillip ACT Information Memorandum For Sale by Deadline Private Treaty | Offers Closing 4th April 2019 Boundaries are indicative only 2 Unit 3/46 Botany Street, Phillip ACT , Information Memorandum Contents Introduction 4 Investment Features 6 Location 8 Location Maps 9 Property Details 10 Lease Details 12 Financial Summary 13 Tenant Profile 14 Sale Process 15 Property Management 16 Disclaimer 17 Available on Request Sale Contract Copy of Lease Burgess Rawson 3 Introduction Burgess Rawson are delighted to offer for sale this superb Trek leased investment property, located at unit 3/46 Botany Street, Phillip. This flagship property will be offered for sale by deadline private treaty closing 4th April 2019 unless sold prior. Burgess Rawson Since being established in 1975, our Sales, Leasing, Burgess Rawson’s iconic Portfolio Auctions are held in Property Management, Valuation and Advisory Melbourne and Sydney bringing together a diverse services fulfill the complete and ongoing needs range of national commercial and investment grade of our clients. Burgess Rawson has a network of properties. offices throughout Australia and extensive regional Our renowned auction program, together with a partnerships with local property specialists, giving large pool of eager, qualified investors continues unmatched depth and reach in all commercial to generate premium results. With eight, two day property market sectors. Investment Portfolio Auction events held each year, At every stage of ownership, our clients benefit from Burgess Rawson are the leaders in the selling of quality our specialist knowledge, experience, market insights property investments. and advice. -

Proposed Stage 2 ACT Light Rail Project

Ms Peggy Danaee Committee Secretary JOINT STANDING COMMITTEE ON THE NATIONAL CAPITAL AND EXTERNAL TERRITORIES PO Box 6021 Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Via email: [email protected] Dear Ms Danaee INQUIRY INTO COMMONWEALTH AND PARLIAMENTARY APPROVALS FOR THE PROPOSED STAGE 2 OF THE AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY LIGHT RAIL PROJECT ACT Division of the Planning Institute of Australia – Response to request for a submission Thank you for the opportunity to provide a submission to the above inquiry. The key points of our submission are as follows: 1. The Planning Institute of Australia (PIA) supports investment in public transport to diversify transport options and provide transport choice. 2. The proposal to create the light rail network as part of the National Triangle and through the Parliamentary Zone is within an area of national significance. 3. The Commonwealth, via the National Capital Authority has planning responsibility for Designated Areas, recognised as areas of national significance. The design quality, breadth of consultation and planning outcomes should represent the significance of the area, in particular the Parliamentary Zone. 4. The National Triangle framed by Commonwealth Avenue, Constitution Avenue and Kings Avenue (including City south, Russell and the Parliamentary Zone) is the centre of the public transport network, providing connections to the rest of the Canberra network. Connecting light rail to the Parliamentary Zone south of the lake also opens up future corridors in Canberra’s south. 5. The PIA supports long term infrastructure planning that integrates land use and transport and is informed by strategic planning and high quality urban design. Planning Institute of Australia Page 1 of 17 Australia’s Trusted Voice on Planning AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY c/- PO Box 5427 KINGSTON ACT 2604 | ABN: 34 151 601 937 Phone: 02 6262 5933 | Fax: 02 6262 9970 | Email: [email protected] | @pia_planning Planning Institute of Australia planning.org.au/act 6. -

The Evolution of Town Planning Ideas, Plans and Their Implementation in Kampala City 1903-2004

School of Built Environment, CEDAT Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda and School of Architecture and the Built Environment Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden The Evolution of Town Planning Ideas, Plans and their Implementation in Kampala City 1903-2004 Fredrick Omolo-Okalebo Doctoral Thesis in Infrastructure, Planning and Implementation Stockholm 2011 i ABSTRACT Title: Evolution of Town Planning Ideas, Plans and their Implementation in Kampala City 1903-2004 Through a descriptive and exploratory approach, and by review and deduction of archival and documentary resources, supplemented by empirical evidence from case studies, this thesis traces, analyses and describes the historic trajectory of planning events in Kampala City, Uganda, since the inception of modern town planning in 1903, and runs through the various planning episodes of 1912, 1919, 1930, 1951, 1972 and 1994. The planning ideas at interplay in each planning period and their expression in planning schemes vis-à-vis spatial outcomes form the major focus. The study results show the existence of two distinct landscapes; Mengo for the Native Baganda peoples and Kampala for the Europeans, a dualism that existed for much of the period before 1968. Modern town planning was particularly applied to the colonial city while the native city grew with little attempts to planning. Four main ideas are identified as having informed planning and transformed Kampala – first, the utopian ideals of the century; secondly, “the mosquito theory” and the general health concern and fear of catching „native‟ diseases – malaria and plague; thirdly, racial segregation and fourth, an influx of migrant labour into Kampala City, and attempts to meet an expanding urban need in the immediate post war years and after independence in 1962 saw the transfer and/or the transposition of the modernist and in particular, of the new towns planning ideas – which were particularly expressed in the plans of 1963-1968 by the United Nations Planning Mission. -

Boy-Wives and Female Husbands

Boy-Wives and Female Husbands Item Type Book Authors Murray, Stephen O.; Roscoe, Will DOI 10.1353/book.83859 Publisher SUNY Press Rights Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Download date 24/09/2021 02:52:38 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://www.sunypress.edu/p-7129-boy-wives-and-female- husbands.aspx Boy-Wives and Female Husbands Boy-Wives and Female Husbands STUDIES IN AFRICAN HOMOSEXUALITIES Edited by Stephen O. Murray and Will Roscoe With a New Foreword by Mark Epprecht Cover image: The Shaman, photographed by Yannis Davy Guibinga. © Yannis Davy Guibinga. Subject: Toshiro Kam. Styling: Tinashe Musara. Makeup: Jess Cohen. The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous support of the Murray Hong Family Trust. Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 1998 Stephen O. Murray, Will Roscoe Printed in the United States of America The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution— Non-Commercial 4.0 International License (CC BY-ND 4.0), available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0. For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY www.sunypress.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Roscoe, Will, editor. | Murray, Stephen O., editor. | Epprecht, Marc, editor. Title: Boy-wives and female husbands : studies in African homosexualities / [edited by] Will Roscoe, Stephen O. Murray, Marc Epprecht. Description: Albany : State University of New York Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2020034064 | ISBN 9781438484099 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781438484112 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Homosexuality—Africa—History.