Chinese Intergenerational Relations in Modern Singapore Göransson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heart to Heart Bound Together Forever

Volume 7 • Issue 1 February 2002 Heart to Heart Bound Together Forever FAMILIES WITH CHILDREN FROM CHINA – OREGON AND SW WASHINGTON The Gift of Language by Charlie Dolezal id you every have any regrets about your childhood? ber going to the FCC Saturday morning Mandarin classes. D Did you ever wish you had done something Hannah went for several months and never said a word. differently? Well, I do. I regret never having taken a foreign Then, one day in her car seat, she sang one of the songs. language. It wasn’t required. Language arts was not my best She was listening. She took it in. Children are like sponges. subject, so how could I excel at in another language? My We are fortunate here in Portland to have so many parents didn’t push me to take one. My dad always told language immersion programs, both public and private, to the story how his parents made the decision upon immigrating choose from. As FCC members we all have a tie to to America that their kids had to learn English to be a real Mandarin. We have elementary Mandarin programs at Americans and leave the “old” country behind. Thus, they never Woodstock (public school) and The International School taught my dad and his brothers and sisters their native tongue. (private school). In addition, there are immersion pro- When did I regret it? I regretted it on my first trip to Europe grams in French, German, Spanish, and Japanese to avail- with three college friends. We got a 48-hour visa to visit able in our community. -

An In-Depth Look at the Spiritual Lives of People Around the Globe

Faith in Real Life: An In-Depth Look at the Spiritual Lives of People around the Globe September 2011 Pamela Caudill Ovwigho, Ph.D. & Arnie Cole, Ed.D. Table of Contents Buddhists......................................................................................... 4 Faith Practices............................................................................... 5 Spiritual Me ................................................................................... 6 Life & Death .................................................................................. 6 Communicating with God............................................................... 7 Spiritual Growth ............................................................................ 7 Spiritual Needs & Struggles ........................................................... 8 Chinese Traditionalists ..................................................................... 9 Faith Practices............................................................................... 9 Life & Death ................................................................................ 10 Spiritual Me ................................................................................. 11 Communicating with God............................................................. 11 Spiritual Growth .......................................................................... 11 Spiritual Needs & Struggles ......................................................... 11 Hindus .......................................................................................... -

CNY-Activity-Pack-2021.Pdf

This is an activity pack to learn about the culture and traditions of Chinese New Year as observed in Malaysia. Due to the pandemic, many Girl Guide/Girl Scout units may not be able to meet face to face, therefore, leaders/units may adapt the activities to be done by individuals at home or in a group through virtual events. Suggested activities are simple and accompanied by references for leaders/units to do further research on each topic. A couple of references are suggested for each topic and these are not exhaustive. Leaders/units can do more research to find out more information. Individuals/units can choose activities they like from the list. It is not necessary to do all the activities listed in each topic. Most important is enjoy them with people whom you care! Due to the lack of time, we were not able to turn this into a nicely designed activity pack. We hope that by learning about culture, we could develop better understanding between people of different ethnicities as part of the peacebuilding process, and at the same time, having fun. Please note that the activities and descriptions are mostly based on the authors’ own knowledge and experience plus information from the internet. We apologize in advance should there be any parts that are inaccurate or cause discomfort in anyone. We would also like to record appreciation to the websites we referred in compiling information for this page. This is a volunteer project, not through any organisations, therefore there is no official badge linked to this pack. -

ST/LIFE/PAGE<LIF-006>

C6 life happenings | THE STRAITS TIMES | FRIDAY, MARCH 20, 2020 | FOOD Eunice Quek Food Correspondent recommends PROMOTIONS Picks Lawry’s The Prime Rib Take your child to the steak restaurant for a meal this month. Children under the age of 12 dine for free with every adult a la carte main course or set menu ordered. Food The promotion is limited to a maximum of two free children’s meals a table, a bill. The complimentary meal offered is the Lawry’s three-course kids’ set menu. WHERE: 333A Orchard Road, 04-01/31 Mandarin Gallery, Mandarin Orchard Singapore MRT: Somerset WHEN: Valid daily for lunch & dinner till March 31, 11.30am - 10pm (last order, Sun - Thu), 11.30am - 10.30pm (last order, Fri, Sat & eve of public holidays) TEL: 6836-3333 INFO: www.lawrys.com.sg Art’s New Spring Menu Italian fine-dining restaurant Art celebrates spring with a new menu. Highlights include the Tender milk-fed piglet rack, which comes with young zucchini, vincotto and grape sauce, and Khorasan wheat tagliolini, which comes with sea urchin and Nubia red garlic in creamy sauce. WHERE: 05-03 National Gallery Singapore, 1 St Andrew’s Road MRT: City Hall WHEN: Daily, noon - 2pm (lunch) & 6.30 - 10pm (dinner) PRICE: Three courses ($78), four courses ($108), five courses ($138), premium five courses ($188) TEL: 6866-1977 INFO: www.artrestaurant.sg Tanuki Raw’s Lunch Bowls Enjoy the daily lunch specials with a selection of SAVOURY DELIGHTS BY OLLELLA usual cabbage. Instead, the main donburi (Japanese rice bowls), including truffle I have been a long-time fan of Ollella, a ingredients are chayote (a type of yakiniku don, chirashi donburi and Okinawan black sugar home-grown business which gourd), green papaya, long beans and miso-baked rice. -

The History of Red Envelopes

The History of the Red Envelopes and How to Use them in the Year of the Rooster 2017. (Hong Bao, Lai See, Ang Pow, Sae Bae Don, Ang Bao) There will be further 2017 updates on our Facebook and Feng Shui blog so bookmark them now below… © 2017 Updated by Daniel Hanna Are you really prepared for 2017? For children and teenagers celebrating Chinese New Year, the Ang Pow is a very exciting part of the celebrations. Even though they are often referred to as red envelopes they are also coloured in a golden colour as red and gold to the Chinese are seen as very auspicious. Red envelopes have many different names; they are more commonly known as “Ang Pow” “red packets” “lai see” “laisee” “hung bao” or “hung-bao”. These envelopes are seen as very lucky when given as a gift and even more fortunate when they contain some money. The main use of red envelopes is for Chinese New Year, birthdays, weddings or any other important event. In recent years, a lot of companies have added their own take to the Ang Pow by adding their company branding on the front which may not necessarily bring good fortune to the receiver although it is nice to see western companies taking on eastern traditions. Some very popular Ang Pow’s in China these days are made with cartoon characters on the front such as hello kitty and Pokémon and you can find them all across the world. The image on the front of an Ang Pow is traditionally a symbolisation of blessings and good wishes of long life, success and good health to the receiver of the envelope and is a great honour to receive. -

The Pioneer Chinese of Utah

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1976 The Pioneer Chinese of Utah Don C. Conley Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Chinese Studies Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Conley, Don C., "The Pioneer Chinese of Utah" (1976). Theses and Dissertations. 4616. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4616 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. THE PIONEER CHINESE OF UTAH A Thesis Presented to the Department of Asian Studies Brigham Young University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Don C. Conley April 1976 This thesis, by Don C. Conley, is accepted in its present form by the Department of Asian Studies of Brigham Young University as satisfying the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. Russell N. Hdriuchi, Department Chairman Typed by Sharon Bird ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author gratefully acknowledges the encourage ment, suggestions, and criticisms of Dr. Paul V. Hyer and Dr. Eugene E. Campbell. A special thanks is extended to the staffs of the American West Center at the University of Utah and the Utah Historical Society. Most of all, the writer thanks Angela, Jared and Joshua, whose sacrifice for this study have been at least equal to his own. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii INTRODUCTION 1 Chapter 1. -

Press Release After the Dog Comes The

Press Release After the dog comes the pig Freudenberg employees talk about Chinese New Year customs and traditions Weinheim, Germany February 5, 2018 Good fortune, wealth Press Contact Cornelia Buchta-Noack and contentment - the Year of the Pig promises all this and Freudenberg & Co. KG Head of Corporate Communications more. February 5 is the first day of the Chinese New Year. Tel. 06201 80-4094 The day also marks the beginning of a new chapter in the Fax 06201 88-4094 [email protected] Chinese zodiac. The year of the dog gives way to the year of www.freudenberg.de the pig. The New Year, also known as the Spring Festival, is Martina Muschelknautz the most important traditional holiday in China. Three Freudenberg & Co. KG Corporate Communications Chinese Freudenberg employees based in Weinheim tell us Tel. 06201 80-6637 Fax 06201 88-6637 about their customs and traditions – the most important [email protected] www.freudenberg.de dishes for wealth and good fortune, money gifts via group chats and a TV gala lasting several hours. “Have you already eaten?” is a typical Chinese greeting and reveals the significance of food in Chinese culture. Chinese cuisine is even more important at New Year. Just a few days prior to the holiday, an exodus of people begin the long journey home to enjoy a traditional family feast. Almost every dish has a special meaning for the New Year. Traditional dishes include Chinese dumplings - so-called Jiaozi. As Jiaozi resemble shoe- shaped gold bars, they promise wealth, good fortune and prosperity for the coming year. -

FULLTHESIS Noor Dzuhaidah IREP

THE LEGAL REGULATION OF BIOSAFETY RISK: A COMPARATIVE LEGAL STUDY BETWEEN MALAYSIA AND SINGAPORE Noor Dzuhaidah binti Osman January 2018 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Nottingham Trent University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy COPYRIGHT This work is the intellectual property of the author. You may copy up to 5% of this work for private study, or personal, non-commercial research. Any re-use of the information contained within this document should be fully referenced, quoting the author, title, university, degree level and pagination. Queries or requests for any other use, or if a more substantial copy is required, should be directed in the owner(s) of the Intellectual Property Rights. ABSTRACT The Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety to the Convention of Biological Diversity, that was adopted on the 29 th January, 2000 and became into force on 11 th September 2003, is the most important global agreement on biosafety that governs the transboundary movement of living modified organisms for the protection of human health and environment . Malaysia and Singapore were among the countries participated during the Protocol negotiations. In the end, Malaysia signed the Protocol on 24 th May, 2000 and ratified it on 2 nd December, 2003. However, Singapore ended up not being a party to it. This study analyses the different stances taken by both countries towards the Protocol, in the domestic biosafety laws implementations. This study, in summary, is a comparative legal study with the Singapore legal and institutional framework of biosafety laws. This thesis examines Malaysian compliance towards the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety by analysing the current domestic legal and institutions’ compliance with the Protocol requirements. -

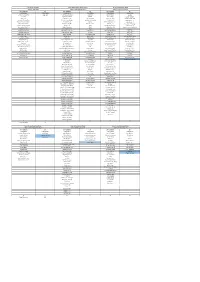

Qr + Terminal Qr Qr + Terminal Qr Qr +

Zion Road Food Centre Name: 628 Ang Mo Kio Hawker Centre Name: Maxwell Hawker Centre Address: 70 Zion Road Address: 628 Ang Mo Kio Ave. 4 Address: 1 Kadayanallur Street QR + TERMINAL QR QR + TERMINAL QR QR + TERMINAL QR Trading Name Trading Name Trading Name Trading Name Trading Name Trading Name C.T Hainan Chicken Rice Swee Huat Hoe Ping Cooked Food Cheo Beck Maxwell Mei Shi K3 Cafe Teck Bee Ang Mo Kio Cold Hot 118119 Ah Tan Wings Lao Ban Maxwell Fresh Taste Li Xiang Fish Soup Dian Xian Mian Traditional Coffee Maxwell Chicken Rice Xin Fei Fei Wanton Mee Wah Kee Prawn Noodles Tanglin Hainan Curry Rice The Green Leaf Dubai Shawarma Shuang Yu Mixed Veg Rice Qiong Mei Yuan Qing Ping SMH Hot And Cold Drinks 69 Coffee Stall House Of Soya Beans Curry Mixed Veg Rice Green Supermart Tong Fong Fa Yi Jia Teochew Porridge Soon Lee Pig Organs Soup Konomi Zen DXM Eng Hiang Beverages Teochew Porridge Xiao Long Ban Mian Fish Jin Mao Hainanese DXM Ho Peng Coffee Stall Hajmeer Kwaja Muslim Food Chong Pang Huat Ri Xin Leng Ri Yin Pin DXM Hum Jin Pang Wonderful Hainanese Chicken Rice Black White Carrot Cake Susan Fashion Xing Xing Tapioca Kueh He Ji Wu Xiang Riverside Good Food Heng Huat Soup House Lai Heng Cooked Food Beng Seng Double Happy Bak Kut Teh Zenjie Traditional Khan Meat Supplier Korean Cuisine Quan Yuan 28 Zhu Chao Nasi Lemak 67 Beauty Taylor Hong Xiang Hainanese Teo Chew Fishball Noodle Xing Feng Hot & Cold Delisnacks Hiap Seng Lee Rojak Popiah & Cockle Fresh Fruit Juice Chong Pang Village Foy Yin Vegetarian Food Tiang Huat Peanut Soup Soon -

The Russian Orthodox Church in Taiwan

Min-Chin Kay CHIANG LN “Reviving” the Russian Orthodox Church in Taiwan Abstract. As early as the first year into Japanese colonization (LcRd–LRQd), the Rus- sian Orthodox Church arrived in Taiwan. Japanese Orthodox Church members had actively called for establishing a church on this “new land”. In the post-WWII pe- riod after the Japanese left and with the impending Cold War, the Russian commu- nity in China migrating with the successive Kuomintang government brought their church life to Taiwan. Religious activities were practiced by both immigrants and local members until the LRcSs. In recent decades, recollection of memories was in- itiated by the “revived” Church; lobbying efforts have been made for erecting mon- uments in Taipei City as the commemorations of former gathering sites of the Church. The Church also continuously brings significant religious objects into Tai- wan to “reconnect” the land with the larger historical context and the church net- work while bonding local members through rituals and vibrant activities at the same time. With reference to the archival data of the Japanese Orthodox Church, postwar records, as well as interviews of key informants, this article intends to clarify the historical development and dynamics of forgetting and remembering the Russian Orthodox Church in Taiwan. Keywords. Russian Orthodox Church, Russia and Taiwan, Russian émigrés, Sites of Memory, Japanese Orthodox Church. Published in: Gotelind MÜLLER and Nikolay SAMOYLOV (eds.): Chinese Perceptions of Russia and the West. Changes, Continuities, and Contingencies during the Twentieth Cen- tury. Heidelberg: CrossAsia-eBooks, JSJS. DOI: https://doi.org/LS.LLdcc/xabooks.eeL. NcR Min-Chin Kay CHIANG An Orthodox church in the Traditional Taiwanese Market In winter JSLc, I walked into a traditional Taiwanese market in Taipei and surpris- ingly found a Russian Orthodox church at a corner of small alleys deep in the market. -

Title: Understanding Material Offerings in Hong Kong Folk Religion Author: Kagan Pittman Source: Prandium - the Journal of Historical Studies, Vol

Title: Understanding Material Offerings in Hong Kong Folk Religion Author: Kagan Pittman Source: Prandium - The Journal of Historical Studies, Vol. 8, No. 1 (Fall, 2019). Published by: The Department of Historical Studies, University of Toronto Mississauga Stable URL: http://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/prandium/article/view/16211/ 1 The following paper was written for the University of Toronto Mississauga’s RLG415: Advanced Topics in the Study of Religion.1 In this course we explored the topics of religion and death in Hong Kong. The trip to Hong Kong occurred during the 2019 Winter semester’s Reading Week. The final project could take any form the student wished, in consultation with the instructor, Ken Derry. The project was intended to explore a question posed by the student regarding religion and death in Hong Kong and answered using a combination of material from assigned readings in the class, our own experiences during the trip, and additional independent research. As someone with a history in professional writing, I chose for my final assignment to be in essay form. I selected material offerings as my subject given my history of interest with material religion, as in the expression of religion and religious ideas through physical mediums like art, and sacrificial as well as other sacred objects. --- Material offerings are an integral part to religious expression in Hong Kong’s Buddhist, Confucian and Taoist faith groups in varying degrees. Hong Kong’s folk religious practice, referred to as San Jiao (“Unity of the Three Teachings”) by Kwong Chunwah, Assistant Professor of Practical Theology at the Hong Kong Baptist Theological Seminary, combines key elements of these three faiths and so greatly influences the significance and use of material offerings, and explains much of what I have seen in Hong Kong over the course of a nine-day trip. -

S/N Name of Merchant / Hawker Stall Trade of Services/Goods Address

The list is updated as of 28 August 2020 s/n Name of Merchant / Hawker stall Trade of services/goods Address Unit number Postal Code Division 1 Swee Heng Bakery Confectionery Blk 548 Woodlands Drive 44, Vista point #01-19 730548 Admiralty 2 Kopitiam @ Vista Point - Drinks Stall F&B Blk 548 Woodlands Drive 44, Vista point #01-21 730548 Admiralty 3 Vista Point - Basic Point Pte Ltd Others Blk 548 Woodlands Drive 44, Vista point #02-01 730548 Admiralty 4 Vista Point - Digital Universe Pte Ltd Others Blk 548 Woodlands Drive 44, Vista point #02-09 730548 Admiralty 5 Vista Point - Yufu Electrical Traders Others Blk 548 Woodlands Drive 44, Vista point #02-29/30 730548 Admiralty 6 Vista Point - Paparazzi Hairstylists Hair Salon/Barber Shop Blk 548 Woodlands Drive 44, Vista point #02-32 730548 Admiralty 7 Vista Point - Lenscraft Optics Others Blk 548 Woodlands Drive 44, Vista point #02-33 730548 Admiralty 8 Koufu 548 - Traditional Yong Tau Foo F&B Blk 548 Woodlands Drive 44, Vista point #02-34 730548 Admiralty 9 Koufu 548 - Japanese & Korean Cuisine F&B Blk 548 Woodlands Drive 44, Vista point #02-34 730548 Admiralty 10 Koufu 548 - Siang Kee Noodle House F&B Blk 548 Woodlands Drive 44, Vista point #02-34 730548 Admiralty 11 Koufu 548 - Ji Ling Vegetarian F&B Blk 548 Woodlands Drive 44, Vista point #02-34 730548 Admiralty 12 Koufu 548 - Thye Guan Frangrant Hot Pot F&B Blk 548 Woodlands Drive 44, Vista point #02-34 730548 Admiralty 13 Koufu 548 - Chong Ling Mixed Vegetable Rice F&B Blk 548 Woodlands Drive 44, Vista point #02-34 730548 Admiralty 14